BEGINNING THE “THIRD CHAPTER” EN MASSE

In 2009, Cubans numbered 11.2 million, 2.1 million living in Havana.[1] Both nationally and in the capital, total population is at a virtual standstill and its composition is getting significantly older. The reasons have to do with low birth rates, increased longevity and migration.

Cuba has the lowest crude birth rate in Latin America and the Caribbean, at 10.5 for the 2005–2010 period and predicted to decrease to 10.2 for 2010–2015.[2] The total fertility rate (children per woman) has decreased from 1.83 in 1990 to 1.59 in 2008, rising slightly to 1.70 in 2009—well below the 2.2 required to assure generational replacement. Since 1978, the number of girl children born to women (gross reproduction rate) has remained under 1.0, reaching 0.82 in 2009, again below the rate needed to sustain population growth. Paradoxically, while such rates remain low, child survival rates continue to rise, with under-5 child survival at 99.4% and infant mortality at 4.8 per 1000 live births, both figures rivaling those in high-income countries.[3]

The reasons for declining birth rates are myriad, and include high levels of education attained by Cuban women (56% of working women have high school diplomas compared to 44% of working men; 18% of women workers are university graduates compared to 11% of their male colleagues) as well as their relatively broad incorporation into the workforce (over 37% of working-age women are on the job).[4] In addition, family planning is universally accessible through the public health care system. No doubt, negative factors also play a part, such as family financial insecurities inherent in the economic crises that have bedeviled Cuba since the early 1990s. So, too, as we will see later, does the housing shortage play a role, obliging young couples to live in sometimes cramped quarters with relatives. All these factors contribute to the decision to have fewer children. As a result, in Havana itself, the average family unit has decreased in size to 3.8 members.

The tilt towards a larger population group aged 60 or over is also influenced by greater longevity: life expectancy now reaches 80 years for women and 76 for men.[3] Finally, external migration also plays a role, with Havana contributing 65% of the country’s emigrants, who are mainly young men between the ages of 25 and 35, white, and high school or university graduates.[5]

As a result of these inter-related factors, by the new millennium Cuba’s was one of the fastest aging societies in Latin America, the percent of its citizens 60 and over comparable to Argentina and Chile, and only surpassed by Uruguay. In 2009, 17.4% of all Cubans were 60 and over, a total of nearly two million people. If current trends continue, Cuba’s National Statistics Office estimates that by 2030, 3.4 million Cubans will be older adults in this age group, or over 30% of the population, becoming the oldest nation in Latin America and the Caribbean, and, by 2050, one of the 11 oldest countries in the world.[1,6]

More people living longer, coupled with low birth rates, has clear economic and social implications at both macro and micro levels. More people will be living longer after they retire: in 2009, retirement age was set at 60 for women and 65 for men, meaning that retirees will be living an average of 15 to 20 years after leaving their jobs. At the macro level, and unlike other Latin American countries where the economically active population is growing, by 2009, there were 534 older adults and children aged 0–14 years to every 1000 adults aged 15–59, with a tendency towards increasing dependence in the coming years.[1,6,7] This translates into expanded expenditures on social security made from a shrinking economically productive base. The retiree will also feel the pinch, since he or she will be living on a fixed, reduced income, which, despite recently enacted pension increases, is adversely affected by the devaluation of the Cuban peso since 1989.[8]

People entering the “third chapter” of their lives also have special needs determined by such processes as physical deterioration, reduced mobility, chronic illness, weakening or dysfunctional family and social networks, psychological pressures including reduced self-esteem, and decreasing mental capacity. This generates a broad social need to creatively consider and address these processes, opening doors to a fulfilling older adulthood amidst reduced economic alternatives at both the macro and micro levels.

HAVANA: NO CITY FOR OLD PEOPLE

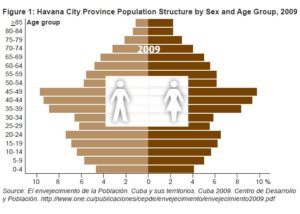

The situation in Cuban cities is even more complex, since this is where the aging population is concentrated: those aged 60 or more constitute 17.7% of urban dwellers, while in Havana this proportion is 19.5% (Figure 1). The demographic dependency ratio for Havana is also higher than the national: 543 compared to 534. Finally, the absolute number of older adults in Havana City province—418,660—is double the number for any other Cuban province.[1]

Government policies in the revolutionary period (from 1959) have targeted the historic imbalance between Havana’s relatively high level of infrastructure, industry, services and recreational opportunities compared to the country’s interior. Thus, major investments in everything from electrification to health, education and industrial development were concentrated outside the capital. One result was that migration towards Havana was minimal until the economic crisis of the 1990s; and once again slowed when migration was further regulated in 1997. Thus, Havana has grown much slower than other Latin American capitals, requiring nearly 50 years to double its population.

Figure 1: Havana City Province Population Structure by Sex and Age Group, 2009

Yet, structurally and socially, the Cuban capital is not prepared to meet the varied demands of a growing population of older adults. Nearly 80% of today’s city was built between 1902 and 1958, with a tendency to geographically expanding urbanization rather than replacement of existing structures. This expansion halted shortly after the 1959 revolution with the first Urban Reform Law of 1960, which ended land speculation and also opened the way for dwellers to own the homes they were living in. Today, some 90% of Cuban homes are owned by their residents.

Havana has about 690,000 housing units, their status classified by the National Housing Institute as in good, fair or poor repair. In 2005, the provincial government reported 64% in good repair, 20% in fair condition, and 16% in poor condition, not including another 60,000 units that were declared uninhabitable and in need of total replacement.[9]

The city’s housing situation—and deficit—is more complex and pronounced than in the rest of the country. In Havana’s central municipalities, 85% of the housing stock is over 80 years old; and the remainder between 40 and 80 years old. Construction carried out over the last five decades, mainly new housing projects in the periphery, now accounts for just 20% of the city’s total housing stock. Today, we see a housing shortage revealed primarily in multi-generational households, coupled with accumulated needs for repairs and maintenance that neither public funds nor homeowners have been able to sufficiently address.[10]

From the perspective of equity and social inclusion, Havana’s infrastructure and services are inadequate, and still more inadequate for older adults. In the city inherited by the 1959 revolution, the best buildings and services were concentrated in the central and coastal municipalities. For example, the most and best theaters and movie houses were found there; so, too, the restaurants and commercial centers. The periphery had little to offer. Since that time, many of the existing structures have deteriorated, and with the exception of health services, childcare centers and schools, the general level of low-cost services and recreational activities has actually decreased. Added to this are the architectural barriers represented by buildings with stairs-only entrances, without washroom facilities designed for older or disabled persons, limiting their access and contributing to social isolation.

RETHINKING HABITAT FOR HAVANA’S OLDER ADULTS

By 2020, Cuba’s baby-boom generation of the 1960s will begin to retire. These people are better educated than generations before them: they read more, they use computers, they enjoy different pastimes and have different quality-of-life expectations. They are also predominantly women, especially in Havana, where 22.0% of women and only 16.9% of men are now 60 or older.[1]

Such changes in the profile of older adults offer further reason to rethink how the city of Havana can be “re-engineered” to comprehensively meet the challenge of an aging population, making efficient and effective use of limited resources. Recent experiences in various fields may shed light on new directions:

Housing 156 homes for the aged (37 in Havana) provide live-in care throughout Cuba for some 9,000 seniors,[3] primarily those who do not have family caregivers and cannot care for themselves. This, of course, is not a solution for the majority of older adults.

Many today live with relatives, but they are also the main dwellers in the 10% of Havana’s housing units that are single-occupancy. [11] Assisted-living housing presents a potential alternative— small, clustered units built or remodeled at low cost. Such an option would not only improve the quality of life for live-alones, allowing them to remain independent, but also would free up their previous housing for families in need.

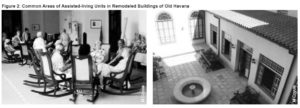

One example is taking place in Old Havana, where 54 older adults have moved into apartments especially designed to meet their needs, and where call buttons alert management in case of emergency (Figure 2). The residents also benefit from the facilities of the Convento de Belen Day Center, which caters to older adults in the community, attracting some 600 daily for various programs, including exercise, discussion, and workshops in visual arts, music and dance. The premises also has a pharmacy, physical therapy unit and ophthalmology/optometry services.[12]

In any case, options need to be explored to “retrofit” the housing where older adults live to cater to their needs.

Accessible services and opportunities Decentralization of services—vital and recreational ones—is essential to improve quality of life for older adults, whose mobility is often reduced by both physical and financial limitations. Moving physical therapy, expanded laboratory, endoscopy and other services from hospitals to community-based polyclinics offers one effective example of such an approach.[13]

The Senior Centers (Casas de Abuelos), of which there are 233 in the country and 25 in Havana supported by the health system, offer caregiving, meals, and social and recreational activities during the day for older adults.[3] This is especially important for those who either live alone or are home alone while other family members are at work or school.

In another sphere, the Older Adult University, an outgrowth of the University of Havana, now has over 600 classrooms in local institutions and centers across the country—many in the capital—bringing continuing education opportunities to the community level. Inter-generational concerns, living an active life at an older age, and other issues particularly relevant to this age group are central to the curriculum.

Figure 2: Common Areas of Assisted-living Units in Remodeled Buildings of Old Havana

Social and participatory organizations The Senior Circles (Circulos de Abuelos), supported by family doctors and polyclinics, offer a good example of how a small investment can impact many peoples’ lives—in this case, offering opportunities for regular exercise promoting physical and mental health, plus essential social contact. By 2005, over 700,000 older adults across Cuba were participating in these circles.[14]

The Group for the Comprehensive Development of Havana (GDIC, its Spanish acronym) and other institutions have also worked for years in the Neighborhood Transformation Workshops, an approach that integrates older adults in a participatory framework of local change and development.

Local financing Limited resources have thus far been available at local government levels to make even small changes that nevertheless could bring important benefits to older adults—such as elimination of architectural barriers. Some local Popular Councils— the most grassroots government body—have raised modest funds within their communities. Taxes on income from a broader range of self-employed workers may now generate greater municipal revenues, which could mean expanded opportunities for planning and investment, administered by the communities themselves.

RENEWING AN OLD CITY FOR LONGER-LIVING PEOPLE

Addressing the economic, political, social and cultural complexities presented by an aging population in an aging city requires comprehensive attention and research by institutions not only in the health field—such as the Research Center on Longevity, Aging and Health (CITED, its Spanish acronym)—but also involving specialists in other spheres and older adults themselves.

Havana will celebrate its 500th anniversary in 2019—proud not only of historic Old Havana, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but also of its broader heritage of eclectic architectural styles and periods—with one of the oldest resident populations in the Americas. ‘Old Havana’ will be ‘old Havana’ indeed. Hopefully, we will reach this milestone not only older, but also wiser when it comes to a conceptual rethinking of how to meet the material, social, cultural and spiritual needs of older Habaneros.