INTRODUCTION

In 2013, factors such as forcible displacement, generalized violence and human rights violations resulted in the movement of 51.2 million people within or outside of their home countries: some 16.7 million were refugees.[1] Refugees are individuals who reside outside the country of their nationality and are unwilling or unable to return to their home country based on a well-founded fear of persecution on the basis of race, religion, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.[2] Article 1 of the UN 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (hereinafter referred to as the Refugee Convention) and its subsequent protocol are the foundations upon which refugee status determination is based. Asylum seekers, by contrast, are individuals who claim to be refugees, but whose claims have not yet been definitively determined.[1] In 2013, 1.1 million individuals worldwide identified as asylum seekers.[1]

In reviewing asylum claims to determine refugee status, states can adopt the definition of a refugee per the Refugee Convention or revise their functional definition under their own legal framework. Some countries, such as the USA, allow for protection of persons not meeting all Refugee Convention criteria but still deemed to need international protection.[3] Refugee status grants individuals certain rights, such as non-refoulement—protection against return to a country where they face risk of persecution. Certain rights such as non-refoulement are conferred pending determination of refugee status. Non-refoulement is further protected by article 3 of the UN Convention against Torture, and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, to which the USA is a party.[4] As a result, asylum seekers cannot be returned to their country of origin prior to a review of their claim.

Under US law, asylum seekers who are victims of physical, psychological and/or sexual torture, as well as other forms of maltreatment are entitled to make their asylum claim on the basis of their fear of persecution.[5] If found credible, such claims must be supported by the granting of positive case outcomes.

Nonetheless, asylum seekers face a wide array of challenges before, during and after a decision on their refugee claim has been reached. Many asylum seekers come from challenging and distressing circumstances in their country of origin, having witnessed or directly experienced various forms of violence, including torture and gender-based, physical and/or sexual violence.[6–8] The process of departing their home country may induce additional stressors and risks including poor nutrition, illness, violence and capture (or fear thereof).[9,10] The cumulative effects of these stressors can result in psychological and physical (including at times gynecological) sequelae. Refugees and asylum seekers are at increased risk for mental illness including PTSD, depression, anxiety, suicide and, more generally, self harm.[11–15]

Factors in the host country may exacerbate these effects due to prolonged detention in holding centers while asylum status is determined,[16–18] the process of acculturation,[19] and stress from failed asylum applications. Other challenges include accessing health care, education, legal and employment services, as well as navigating language and cultural barriers.[20,21] These factors may not only make life difficult for asylum seekers, but may also negatively impact the outcome of asylum applications. For example, asylum seekers with PTSD are less likely to be able to recollect key life events and thus, could be deemed unfit within the stated definition of refugees.[22]

Appropriate assessment of asylum seekers taking into account such factors is important to inform the adjudication process and ensure the right to non-refoulement. To address this need, the Atlanta Asylum Network (AAN) was established in 2000 as part of the Emory University Institute of Human Rights. The work of AAN supports an informed adjudication process by providing clinical (physical and psychological) assessments to asylum seekers: its goal is a fair process, not necessarily a particular outcome.

AAN was initially designed as a southeastern satellite for the long-standing nationwide asylum program offered by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). Consisting of volunteer case managers and health professionals, AAN provides physical, psychological and gynecological assessments of asylum seekers, primarily in the state of Georgia, pro bono or at a reduced rate. Each asylum seeker is assigned a volunteer case manager who serves as his/her point person until the asylum seeker receives the immigration court’s decision. The volunteer case manager conducts an intake interview and provides a summary report to the clinician conducting the clinical assessment. Following physical and/or psychological assessment, the clinician writes a legal affidavit. These affidavits are used as clinical evidence in the asylum seeker’s court proceedings. National data from PHR show that 89% of asylum seekers who provided these documents with their asylum application were approved, versus only 37.5% of those without such documentation.[23]

As a component of AAN’s program evaluation, the objective of this research was to assess outcomes among asylum seekers using its services, as well as relation of outcomes to type of service provided, the individual’s geographic origin and English language proficiency.

METHODS

The study was a retrospective examination of program data gathered by AAN between 2003 and 2012. The study population included asylum seekers who received clinical (physical or psychological) assessment during that period, and for whom affidavits were rendered. These affidavits document clinical evidence in support of the asylum seeker’s claim but do not make recommendations as to whether asylum should be granted. Records of those who contacted AAN but never received services were excluded; the study pool was further limited by the fact that AAN only serves clients who have legal representation.

The study protocol was reviewed by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and exempted from full review due to its nature as a program evaluation based solely on administrative records.

The primary variable of interest was the final case outcome, defined as determination of asylum status. Initial data examination revealed that many case outcomes were missing. Therefore, a protocol was developed to gather missing case outcomes. Over a three-week period, study staff contacted the attorney for each missing case outcome by email, telephone, or both at least three times. If missing data were not gathered after at least three attempts, the outcome was listed as lost to followup.

Case outcomes were categorized as follows: granted, denied, withholding of removal, administrative closure, prosecutorial discretion, voluntary departure, pending or lost to followup. These were subsequently collapsed into a single positive or negative outcome variable. Outcomes considered positive were: granted, withholding of removal, administrative closure and prosecutorial discretion. Negatives outcomes included: denied and voluntary departure, the latter per PHR classification.[24] These categories are consistent with those commonly used in work on this topic.[23,24]

Other variables included in the initial analysis were: age, sex, country and region of origin, date of intake, and English proficiency (self-reported). The age variable was based on age at the time of intake into the AAN program, and not at case outcome. The country of origin variable was used to create an original variable, geographic region of origin. Regions were assigned based on the UNHCR categorization of countries into regions. The five regions were: Asia and the Pacific, Africa, Europe, Middle East and North Africa, and the Americas.[25]

Additional analyses were conducted of the data subset for which final case outcomes were available (excluding those lost to followup and whose claims were pending). Geographic case distribution based on region and temporal trends was examined. Other variables included were number and type of clinical assessment performed (physical, psychological and/or gynecological) and self-reported English language proficiency.

Data were extracted from AAN program intake forms, were kept confidential, and did not include an in-depth chart review. We used Epi Info 7 and SAS 9.4 to conduct bivariate and multivariate analyses, including a chi-square test for independence, with significance threshold set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 120 cases for which AAN provided services between 2003 and 2012, 44 (36.7%) were lost to followup and 7 (6%) still had decisions pending. Final outcome data were available for 69 cases (57.5%). Of the total number of asylum seekers, 44 (36.7%) had positive case outcomes, with 40 (33.3%) granted asylum. Other positive outcomes included 2 with administrative closure (1.7%), 1 with prosecutorial discretion (0.8%), and 1 whose removal was withheld (0.8%). The majority of asylum seekers lived in Georgia and went through immigration court in Georgia. Two asylum seekers resided in North Carolina and had their cases heard in North Carolina immigration courts; both received positive case outcomes.

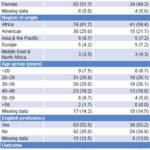

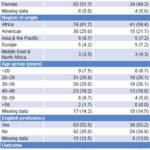

Because of the large number of asylum seekers lost to followup, we compared demographic characteristics of the overall sample to those with known final case outcomes. The two groups were similar for the demographic characteristics examined. Approximately half the clients were female: 51.7% of all asylum seekers and 49.3% of those with known final case outcomes. In both groups, the majority came from Africa: 61.7% of all asylum seekers and 59.4% of those with known final case outcomes. The age range for all asylum seekers was 15–61 years, mean 34. The age range for those with known final case outcomes was 17–56 years, mean age 33. There were no significant differences in terms of sex, region of origin, age, or English proficiency when comparing the overall sample versus those for whom a final case outcome was known (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of asylum seekers with known final outcomea and overall sample

aDetermination of asylum status (positive or negative); cases pending and lost to followup excluded

NA: not applicable

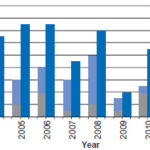

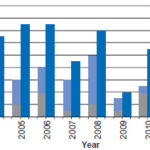

During the ten years of the study, the overall number of asylum seekers assessed by AAN gradually declined, from 17 cases in 2003 to 7 cases in 2012, an average of 11 per year. Similarly, the numbers with known final case outcomes also declined (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total asylum-seeker cases and known final outcomes by year

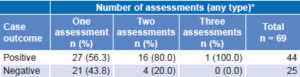

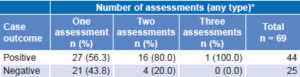

We examined in further detail the subset of asylum seekers with known final case outcomes (n = 69). Most received one type of assessment (48,69.6%) and only one received all three types of assessment. This pattern was maintained even when the data were disaggregated by sex, with 73.5% of men and 64.4% of women undergoing only one type of assessment. Two thirds of asylum seekers with known final case outcome received psychological assessment (65%) and half received physical assessments (52%). One third (32.3%) of women with final case outcomes had gynecological assessments.

Of those with known final case outcomes, 63.8% (44/69) received a positive outcome after receiving an AAN assessment. Over half (56.3%) of those who received one type of assessment (physical, psychological or gynecological) obtained a positive outcome. Among those who received two of the three types of assessment, 80% received positive case outcomes.

Only one client received all three types of assessment and her final case outcome was also positive (Table 2). Asylum seekers who received both psychological and physical assessments were more likely to receive positive case outcomes (p = 0.07) than any other type of assessment combination.

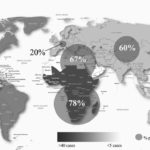

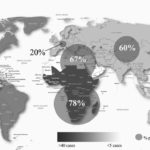

The percentage of positive case outcomes varied across geographic regions. Most cases with known final outcomes came from Africa (41/69); 78% from this region resulted in positive outcomes (32/41). Of asylum seekers from other regions, positive outcomes resulted for 66.7% (2/3) from the Middle East and North Africa; 60% (3/5) from Asia and the Pacific; and 40% (6/15) from the Americas. Asylum seekers from Europe were least likely to receive a positive outcome (20%, 1/5). Figure 2 indicates the region of origin for cases with positive results as well as a dot density visualization of the percentage of cases that received positive case outcomes.

English language proficiency was also an important factor in the final case outcome. Asylum seekers who were not proficient in English were 2.4 times more likely to have negative case outcomes than those who were proficient (p < 0.01).

Table 2: Positive and negative case outcomes by number of assessments (n = 69)

*Physical, psychological, gynecological

Figure 2: Number of cases per region and percent positive outcomes

Adapted from UNHCR World Map 2008[26] Dot diameters proportional to % positive case outcomes among all asylum seekers in region

DISCUSSION

The USA is the second largest single recipient of new asylum claims globally. Between 2003 and 2014, asylum claims ranged from 47,900 in 2009 to 121,200 in 2014.[27,28] The claims in 2014 represented a 36% increase from the previous year.[27] By virtue of several international treaties to which it is a signatory, the US government is obligated to review asylum claims and respect the principle of non-refoulement.

The Atlanta circuit court has the lowest rates for positive case outcomes in the USA, granting only 4.6% of asylum claims from 1994 through 2007, compared to 16.4% in Houston and 40.6% in New York during the same period, and 34.7% nationally from 1996 to 2007.[29–33] Three of the five Atlanta circuit judges were appointed by President George W. Bush (This period overlapped with that of our study for only four years, but we did not have access to data on circuit court composition for the entire study period).[34–36]

There is evidence suggesting that the political nature of federal judicial nominees influences the outcome of asylum claims and, ultimately, the lives of asylum seekers. Specifically, research has shown that political appointees of the second Bush administration are more likely to deny asylum claims.[34] One of these judges, William Cassidy, not only heard the largest number of asylum claims in the USA, he also granted the fewest positive case outcomes (granting asylum to just 71 of 3917 cases, or 1.8%).[37]

Furthermore, female judges are more likely to grant asylum than their male counterparts, with a 44% higher positive case outcome rate.[30] In Atlanta, only one of the five judges is female; she was appointed by President Obama.[35] However, sex of federal judges may not be as strong an indicator of trends in decisions as past professional experience: of male judges, over half (56%) had previously worked for the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) or Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and 83% had worked for other government agencies.[30] Three of the five judges in the Atlanta circuit previously held positions in the INS, DHS and Office of Immigrant Litigation within the US Justice Department.[34,37–39]

The positive outcomes of asylum claimants in our study contrast sharply with the overall record of the courts in Atlanta, since over one third of all claimants receiving AAN services, and 64% of those with known final outcomes received positive court decisions on their claims. This result suggests that affidavits attesting to clinical evidence provide insight into the human experience of asylum seekers pertinent to their court proceedings.

Our data also reveal the importance of psychological, not only physical, assessments; those who received both types of assessment were more likely to receive positive outcomes in court. Psychological assessments document mental health impacts of asylum seekers’ experiences,[23] which may linger and even increase long term, unlike physical evidence that is more subject to degradation over time. In any case, the importance of both types of assessment is underscored by this study.[23]

Our research showed regional disparities among known final case outcomes, consistent with other studies on the impact of region of origin on asylum outcome.[40] Other investigators have identified outcome disparities based on country or region of origin as well as location of asylum claim.[23,29] For example, an asylum seeker from China has a 76% chance of being granted asylum in Orlando, Florida, but only a 7% chance in Atlanta, Georgia, compared to a 47% chance nationally.[33]

While global asylum applications decreased between 2001 and 2010, the USA saw an increase in applications of 13%–17% over the same period.[41] In contrast, the number of asylum seekers assessed each year by AAN has declined over the past decade, while the proportion of cases with positive outcomes has remained constant relative to the overall number of cases assessed. There are several reasons why temporal trends in cases seen over time by AAN may not reflect the same influx of asylum seekers as those seen nationally. AAN is a small program dependent on the support of its volunteer case managers and clinicians; as such, we have been reticent to advertise our services broadly for fear of overwhelming our small support cadre. Most clients are referred to AAN by a small group of lawyers who have previously utilized our services.

Finally, self-reported English language proficiency appears to strongly influence final case outcome. To our knowledge, we are the first to document a relationship between asylum outcome and host-country language proficiency. Further research is needed into the impact of such proficiency on outcomes of asylum seekers.

We have identified three limitations to our study. First, legal representation is an important factor influencing the outcome of asylum cases. Asylum seekers with legal representation receive a positive case outcome three times as often as asylum seekers without representation.[29,30] On occasion, asylum seekers without legal representation were referred by AAN to the Georgia Asylum and Immigration Network for legal support, after which they may have returned to AAN for assessment services. However, the data included in this analysis were limited to asylum seekers who already had legal representation and therefore results may be limited by selection bias.

Second, a large proportion of the sample was lost to followup (and hence, final case outcomes remained unknown). However, as we have shown, there were no significant differences in variables examined between the two groups: those with known and those with unknown final outcomes—in particular, sex, age, region of origin or English language proficiency. Based on these similarities and assuming that the final case outcomes of those lost to followup did not differ from the sample, their rate of positive outcomes would also have been markedly higher than the average in Georgia. It is however possible that cases lost to followup may have differed in some important way that was not examined in this analysis. The delay between intake and case outcome can extend over a period of years, making followup difficult, but clearly an area for program improvement. A systematic plan for routine periodic followup on case status following AAN assessment is critical to a more complete understanding of the value of our services.

Third, with the exception of English language proficiency, the small size of the sample limited the ability to identify other key predictors of case outcome.

CONCLUSION

Based on the data, having a clinical assessment and affidavit in support of one’s asylum claim provides the opportunity for a better informed adjudication process, including respect for the principle of non-refoulement. Other factors that may influence case outcomes include: region of origin, English language proficiency, and number and type of clinical assessments received. This is true, in addition to the varying trends in asylum claim decisions by different courts, a critical factor.

The data presented here provide some guideposts for future work. Areas for programmatic improvement include development of systematic followup and increased community awareness of our services. Even with extremely limited resources, AAN can and should improve ways that we reach asylum seekers and to offer assessments to a larger number. Other organizations serving asylum seekers should be encouraged to see that their clients have ready access to English language instruction and legal representation for their asylum claims.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the many clinicians and student volunteers who have dedicated their time and efforts to the Atlanta Asylum Network over the past 15 years. We are also grateful to Braxton Mitchell, Samantha Luffy, Paul Courtwright, Angela Porcarelli, Katherine Ostrom and Vincent Iacopino for their review of the manuscript in advance of submission.