ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION With a global adult prevalence of 24%, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a global health problem that parallels the worldwide increase of obesity. Its frequency, clinical characteristics and related diseases in Cuba remain unknown.

OBJECTIVE Describe the clinical characteristics, comorbidities and personal habits of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease who are being treated in secondary and tertiary health facilities in seven Cuban provinces.

METHODS A cross-sectional, multicenter study was carried out in 6601 adults seen at gastroenterology outpatient clinics of nine hospitals in seven Cuban provinces from September 2018 through May 2019. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease was diagnosed by abdominal ultrasound. The study included 1070 patients who met the diagnostic and study criteria and agreed to participate. Their personal habits and anthropometric and clinical characteristics, comorbidities and other aspects of their medical histories were recorded.

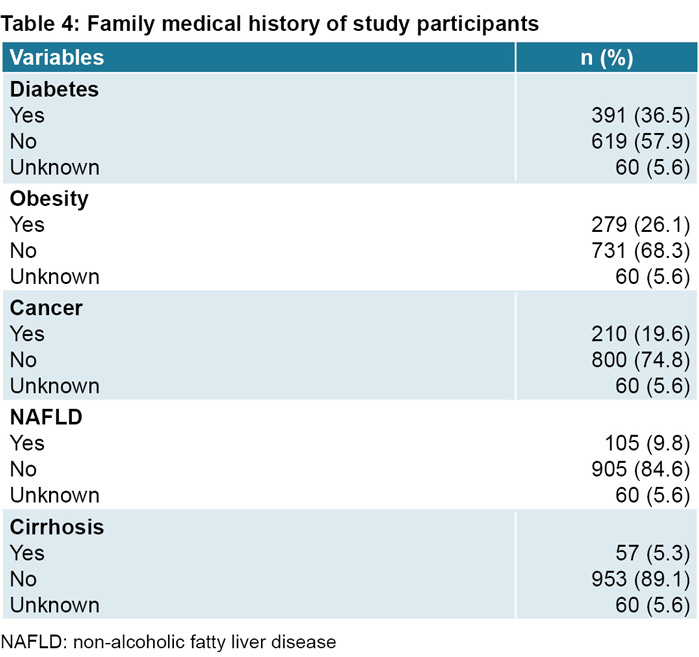

RESULTS Of the 1070 participants, 60.7% (649) were women. Participants’ average age was 54.5 years and average body mass index was 30.5 kg/m2. A total of 397 (37.1%) were overweight and 574 (53.6%) were obese, 945 (88.3%) led a sedentary lifestyle, 564 (52.7%) had high blood pressure, 406 (37.9%) had lipid disorders and 301 (28.1%) were diabetic. While 484 (45.2%) of patients were asymptomatic, the most frequent clinical signs and symptoms were fatigue (262; 24.5%), dyspepsia (209; 19.5%), abdominal pain (306; 28.5%) and hepatomegaly (189; 17.7%). Liver cirrhosis was present in 37 (3.5%) patients at the time of diagnosis. Family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity were identified in 391 (36.5%) and 279 (26.1%) of participants, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in these Cuban patients coincides with that reported in the Caribbean region, which has high levels of obesity, overweight and sedentary lifestyles. Most were asymptomatic, female or had metabolism-related comorbidities such as high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia.

KEYWORDS Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, overweight, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) includes a broad spectrum of metabolic damage associated with fatty deposits in the liver. Its diagnosis excludes other causes that may lead to steatosis, such as excessive alcohol consumption, viral infections, use of steatogenic drugs and/or hereditary disorders.[1]

NAFLD is generally diagnosed in one of three clinical scenarios: patients with abnormal liver enzymes, abnormalities in abdominal imaging or clinical characteristics associated with metabolic syndrome (MetS).[1–3] NAFLD has a diverse clinical presentation, and diagnosis is established when >5% of liver cells are composed of fat. Although a liver biopsy remains the gold standard, noninvasive diagnosis of NAFLD can be carried out via liver imaging in most patients.[4] This clinical form is known as non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), which, by definition, does not progress beyond the first stages of liver disease. Another form is non-alcoholic steatohepatitis accompanied by necroinflammation of hepatocytes with or without liver fibrosis, considered a type of progressive liver disease that leads to fibrosis in 41% of cases. Hepatocellular carcinoma is detected in 2%–3% of patients, with annual mortality rates estimated at 25.6 per 1000 population.[5,6]

IMPORTANCE

This is the first study of the frequency of non-alcoholic liver disease in Cuba, for which there were no national data available at the time this article was written.

The epidemic of chronic liver disease is related to the burden of NAFLD, itself associated with the global increase in obesity.[7,8] An overall prevalence of 24% is reported globally with highest rates in the Middle East (32%) and South America (31%), followed by Asia (27%) and Europe (23%); it is less common in Africa (14%).[8]

Since obesity is associated with presence and severity of NAFLD, it is useful to note that in 2016, 39% of adults worldwide (39% of men and 40% of women) were overweight, and some 13% (11% of men and 15% of women) were obese.[9] Prevalence of excess weight and obesity in Latin America is much higher (62.8% in men and 59.8% in women), explaining why estimated NAFLD rates are increasing in this region. Based on obesity rates, it is estimated that NAFLD prevalence is 26% in Mexico and 15%–20% in Central America.[10–12]

There is a bidirectional association between NAFLD and the components of MetS, as the latter is frequent in NAFLD patients and MetS, in turn, increases risk for NAFLD. NAFLD has been reported in 22.5% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), in 51.3% of those who are obese, 42.5% of patients with MetS, 39.3% of hypertensive patients and 69.2% of those with hyperlipidemia.[4]

NAFLD prevalence is expected to increase, accompanying the upward trend of the global obesity epidemic and the increase observed in type 2 DM.[6] A number of MetS characteristics, particularly type 2 DM and family history of MetS, are risk factors for NAFLD.[13]

In Cuba, overweight and obesity are major health problems and their prevalence increased from 35.5% in 1982 to 44.3% in 2012.[14] In 2010, the rates for high blood pressure (HBP) and type 2 DM were 202.7 and 40.4 per 1000 population, respectively. In 2019, these rates increased to 233 and 66.7.[15,16]

Post-mortem studies of 3317 persons who had been diagnosed with NALFD from 1991 to 2009 revealed that 53% had simple hepatic steatosis, 44.2% steatohepatitis and 2.6% hepatic steatosis with fibrosis or cirrhosis, which highlights the impact this disease has on the liver. In this group, the main cause of death was coronary atherosclerosis.[17]

In Cuba, NAFLD is most often diagnosed in gastroenterology services and its current prevalence in the country is unknown. The purpose of our study was to describe the clinical characteristics at diagnosis, associated comorbidities and personal habits of NAFLD patients seen in secondary and tertiary health facilities in seven Cuban provinces.

METHODS

Design and sample A cross-sectional study was carried out from September 2018 through May 2019 in patients seen at gastroenterology outpatient services in nine Cuban hospitals in seven provinces. These services provided care and monitoring of patients with gastrointestinal, liver, biliary and pancreatic conditions who were referred from community-based polyclinics, family doctors or other specialists. NAFLD diagnosis was based on presence of hepatic steatosis in abdominal ultrasound (US) in the absence of known secondary causes of fat accumulation in the liver, in accordance with the criteria of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.[1]

Personal and family medical history, personal habits, medications used at the time of recruitment and anthropometric data were obtained through a questionnaire developed for that purpose.

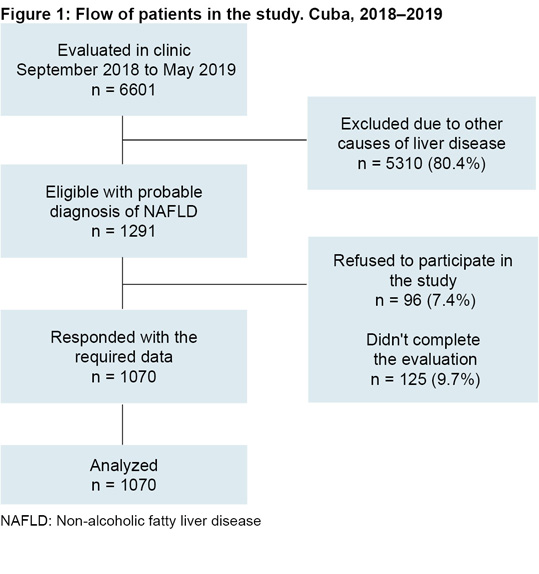

A total of 6601 patients seen in gastroenterology consultations during the study period were considered. Those who met NAFLD diagnostic and our own research criteria were included. Excluded were persons who did not want to participate and those who had other causes of chronic liver disease that can lead to steatosis (Figure 1). Specific traits that led to exclusion were: 1) Alcoholics or individuals who consume more than the maximum recommended weekly alcohol intake,[1] 2) individuals who suffered from chronic autoimmune or inherited liver diseases, 3) individuals who had a history of steatogenic drug use in the six months prior to recruitment date (corticosteroids, methotrexate, tetracycline, amiodarone, diltiazem or tamoxifen), 4) women who were pregnant, breastfeeding or taking hormonal contraceptives, 5) those diagnosed with an active malignant tumor and 6) individuals who tested positive for the surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies. We included patients with a history of HCV infection when the viral load had remained negative for more than a year.

Patients were recruited consecutively during the study period, resulting in inclusion of 1070 persons: 420 men (39.3%) and 650 women (60.7%), with a median age of 55 years and age range 18 to 88 years.

NAFLD diagnosis by abdominal US was defined by presence of liver homogeneous or heterogeneous hyperechogenicity (increased echogenicity with respect to the kidney parenchyma) and attenuation of the liver’s deep structures (diaphragm, vessels, posterior segments). For US diagnosis of steatosis, longitudinal and transverse cuts were made with a low frequency (2.5–5 MHz) convex probe. The following ultrasound scanners were used: Toshiba Aplio 300 (Toshiba Medical Systems Europe, The Netherlands), Aloka SSD-4000 (Hitachi Aloka Medical, Japan) and EPIQ 5 (Philips Ltd, UK). US was performed and diagnosis made by radiologists in all units participating in the study.

Sex, age, area of residence (urban or rural) and skin color (white, black, or mestizo) were recorded according to the classification of Cuba’s National Statistics and Information Bureau (http://www

.onei.gob.cu/).

Actual weight (AW, kg) and height (cm) were measured at the time of study enrollment and body mass index (BMI) calculated. A BMI of <18 kg/m2 was considered underweight, 18–24.9 kg/m2 normal weight, 25–29.9 kg/m2 overweight and ≥30 kg/m2 obese. Waist circumference was measured to ascertain central obesity, a condition associated with metabolic complications. Criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATPIII) were used as reference points for waist circumference: 102 cm in men and 88 cm in women.[18] Anthropometric measurements were carried out during patient recruitment and doctor visits, according to methodology outlined for nutritional studies by the Nutrition and Food Hygiene Institute of Cuba.[19] A calculation was to determine ideal weight (IW), with IW = 0.75 (height in cm–150) +50 and was used to determine the difference between actual and ideal weight according to the expression IW = (AW–IW)*100/IW.

Any medical history of interest was recorded: HBP, type 2 DM, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia (high cholesterol and/or triglycerides), thyroid disease, myocardial infarction and cancer, as well as treatments for these conditions. Medical history considered in first-degree relatives were fatty liver, cirrhosis of the liver, type 2 DM, obesity and cancer.

Personal habits considered included smoking, degree of physical activity and alcohol consumption. These were categorized as follows:

Smoking Smoker: regular or occasional consumption of tobacco products; non-smoker: no consumption of tobacco products.

Physical activity Adapted from WHO criteria on physical activity.[20] Sedentary lifestyle: physical activity <15 minutes <3 times per week during the last quarter, or performing only everyday tasks (occupational activities, traveling, household chores and recreational activities). Moderate or intense physical activity: walking (30 minutes a day ≥5 days a week), games, dancing, non-intense extra work, light weights (≤20 kg) or jogging, racing, aerobics, sports, intense work, heavy weights (≥20 kg).

Alcohol consumption We used guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (USA) to define risks associated with alcohol consumption, as women who consume ≥ 7 standard drink units and men who consume ≥14 every week are at increased risk for alcohol-related problems.

Patients who had no symptoms and in which NAFLD was found incidentally by US ordered for other reasons, or because they had abnormal liver enzymes, were recorded as asymptomatic. Patients were recorded as symptomatic if they reported any symptoms usually linked to NAFLD such as: fatigue, chronic abdominal pain, myalgia and dyspepsia. Among the included signs detected during physical examination were hepatomegaly, xanthomas/xanthelasmas and signs of liver cirrhosis (non-invasive US diagnosis or presence of edema, ascites, splenomegaly, collateral circulation, jaundice, palmar erythema, telangiectasia, petechiae, ecchymosis).

In the initial patient recruitment consultation, blood pressure (BP) was measured and the average of the last two measurements from a total of three measurements, carried out in intervals of one minute with a mercury sphygmomanometer (Kindcare Medical System, China) were recorded. In accordance with the characteristics of the sample, ≥130/85 mmHg was considered high, following the criteria of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association (USA), and the working group for treatment of high blood pressure of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension.[22,23]

Infection by hepatitis B and C viruses was ruled out by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Ultra Micro Analytical System, SUMA, Tecnosuma International, Cuba) for the surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus (HBsAg), the hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) and hepatitis C virus antibody (AcHCV).

To ensure consistency of information reported at participating sites, criteria unification workshops were held for researchers and guidelines were established for information collection and data entry in an Excel (Microsoft, USA) database designed for this purpose. The principal investigator at each center controlled the quality of data and standardization of procedures according to the established protocol.

Ethics The study was approved by the research ethics committees of Cuba’s Gastroenterology Institute and of participating hospitals. Patients were provided with detailed information on study purposes, importance of their participation and benefits. There were no potential risks to patient health. All participants provided written informed consent. The information was kept confidential and in no case will participant identity be revealed.

Diagnostic tools were selected according to principles of maximum beneficence. They followed the Declaration of Helsinki’s Good Clinical Practices guidelines[24] and the Guidelines of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences.[25]

Patients who did not meet the selection criteria were informed of the reasons for their non-inclusion in the study and were sent to specialized clinics in each institution for monitoring and control. Benefits received by the patients included the diagnosis and treatment of diseases.

Statistical analysis Variables were processed in a database created in the statistical package for social sciences for Windows version 21.0 (IBM-SPSS, USA). Descriptive statistics, absolute and relative frequencies, averages and standard deviations and the difference of the average of waist circumference (cm) with respect to the cutoff point in both sexes were calculated (confidence interval, 95%).

RESULTS

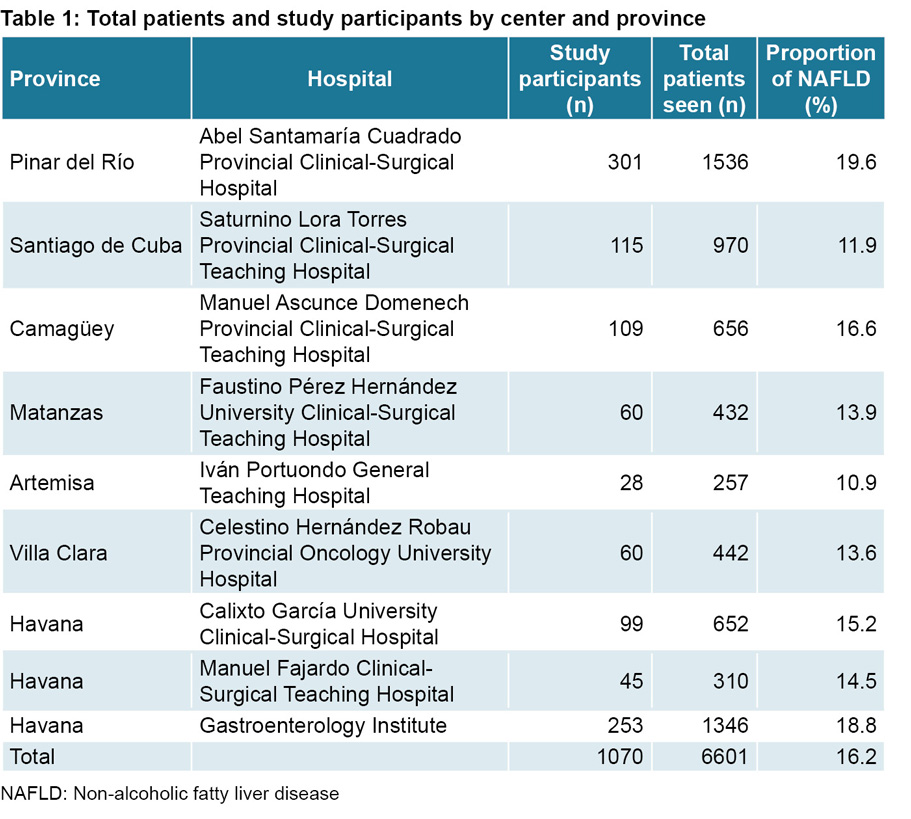

Of the 1070 patients studied, 786 (73.5%) resided in provinces in Cuba’s western region, 169 (15.8%) in the central region and 115 (10.7%) in eastern Cuba; 650 participants (60.7%) were women. NAFLD was diagnosed in 16.2% of all participants. The range of the frequency of patients with NAFLD among centers was 10.8%–19.5% (Table 1).

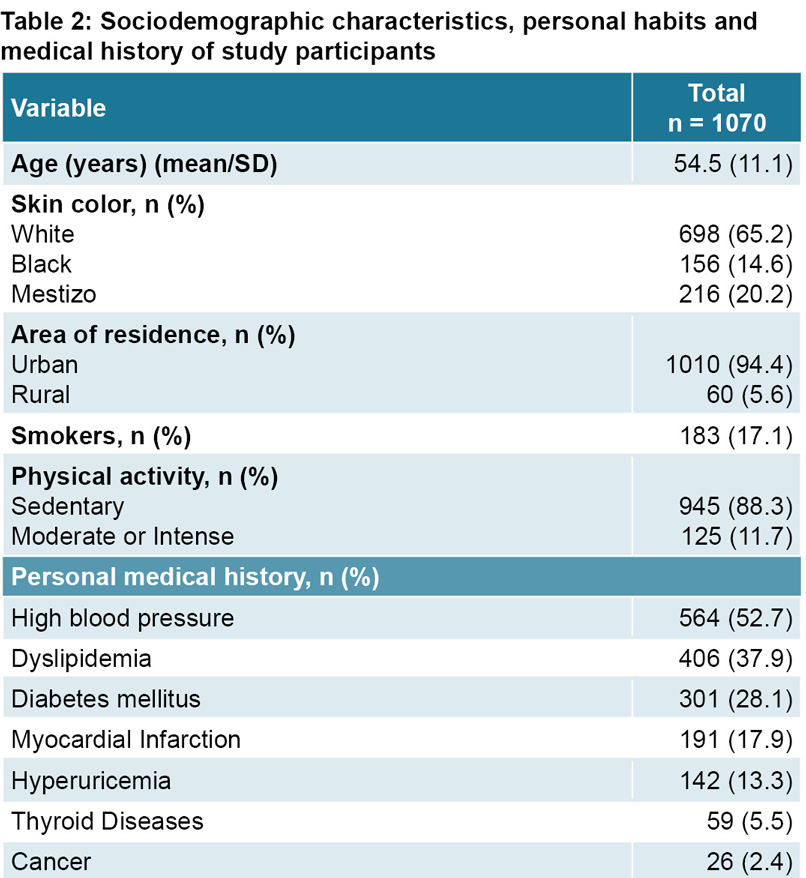

Sociodemographic characteristics, personal habits and personal medical history of the patients revealed that sedentary lifestyle was a frequently observed phenomenon. HBP, dyslipidemia and type 2 DM were the most frequent previous medical issues, followed by acute myocardial infarction, hyperuricemia, thyroid disease and cancer (Table 2).

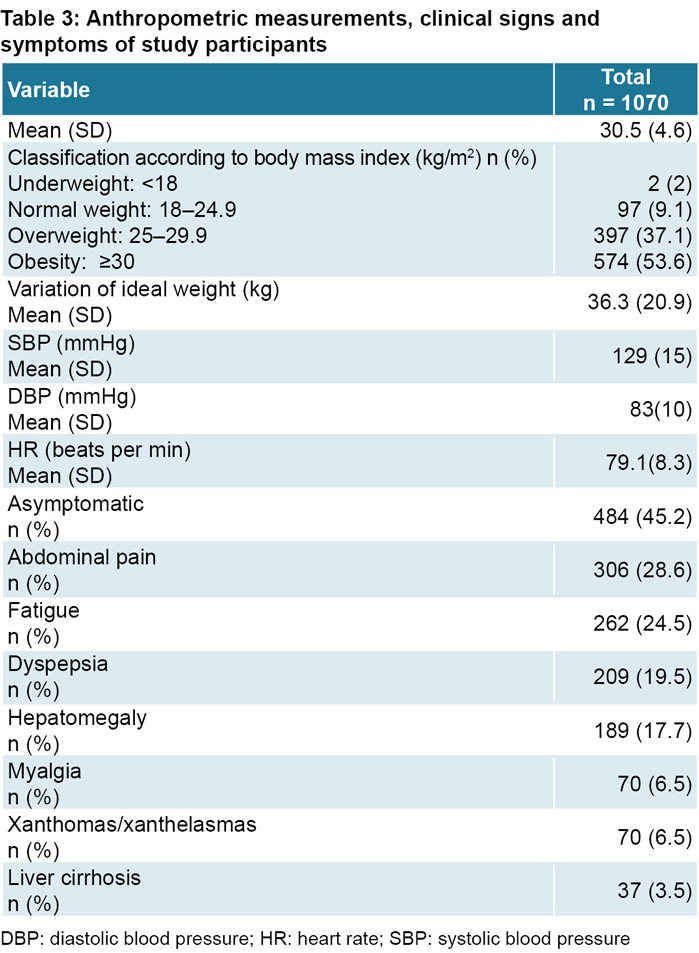

Average BMI of participants was 30.5 kg/m2, or grade I obesity. Distribution of BMI values is shown in Table 3, where the high percentages of overweight and obesity (37.1% and 53.6%, respectively) are of particular note. Average waist circumference was 101.2 cm in men and 99 cm in women. Difference in average waist circumference (cm) with respect to the cut-off point in both sexes was –0.77 (–1.9 to –0.4; p = 0.208) in men and 11.05 (10.0 to 12.0; p <0.001) in women, which implies that women had a rate of central obesity averaging 11 cm above the reference value for abdominal circumference, while men had a rate 0.7 cm below the reference value. Average excess weight of patients with respect to ideal weight was 36.3 kg.

The most frequent symptoms and signs, blood pressure readings, and the proportion of patients with liver cirrhosis can be found in Table 3, in which fatigue, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, and hepatomegaly stand out due to their higher frequencies. Nearly half of the patients were asymptomatic.

The most frequent conditions observed in the patients’ family medical history were type 2 DM, obesity and cancer, with notably high values for the first two (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study on the disease conducted with a large number of patients and in several hospitals in three regions of Cuba. It fills a gap in knowledge on NAFLD frequency in Cuba, although smaller-sample studies have been published.[26–30]

Despite the fact that this study was carried out in each patient’s gastroenterology department, which allows for standardized measuring conditions, its results do not differ from those reported in the literature. Fleischman[31] carried out a multi-ethnic study on atherosclerosis (MESA) in a Hispanic population in the United States, finding a NAFLD prevalence of 33% in those of Mexican descent, 16% in those of Dominican descent and 18% in those of Puerto Rican descent, indicating this disease is common among Hispanics in the USA. Various Latin American countries have reported relatively high rates: Brazil (18.0%–35.2%), Chile (23%) and Colombia (26.6%).[11,32–36] The proportion of patients in this study with NAFLD as measured by center and by province did not exceed 20%.

Prevalence varies according to study method, population characteristics, presence of risk factor, and area of residence, among other factors. NAFLD frequency detected in this study by US was similar to estimates based on obesity prevalence, which are between 15% and 20% for Central America and the Caribbean.[11]

The most recent survey on risk factors and non-communicable diseases in Cubans[37] revealed smoking frequency at 23.7%; excess weight and obesity at 29.8% and 13.7%, respectively; sedentary lifestyle with no physical activity at 40.4%; and prevalence of chronic diseases—such as HBP, type 2 DM and dyslipidemia—at 30.9%, 10% and 4.6%, respectively. Average BMI and waist circumference was 24.5 kg/m2 and 85.1 cm in Cuban men and 25.5 kg/m2 and 81.8 cm in women.

In our study, the proportion of smokers was lower, and the relative frequencies of excess weight and obesity were between two and three times higher than those found in the national survey. The higher levels of central obesity and greater presence of metabolic comorbidities are distinctive characteristics that were expected in the sample with NAFLD, which is related to metabolic syndrome.[13] It should be noted that excess weight and obesity in the Cuban population is rising and is already a health problem in the country.[38]

The effects of tobacco on NAFLD progression is a source of controversy. A systematic review showed that both active and passive smoking are associated with this disease, but the mechanisms of this association are unknown because physical activity, diet type, caffeine consumption and some socio-economic factors act as potential confounding variables.[39] The average prevalence of smoking in the Cuban population is higher than that detected in this study.[37]

The sedentary lifestyle of our study participants was more than twice the rate reported in the national survey (38.3%),[37] and in Latin America and the Caribbean, (39.1%)[14,40] although the rate of sedentary lifestyles among Cubans is one of the highest in the world.[37]

Globally, differences have been reported between men and women in terms of prevalence, risk factors, fibrosis, disease severity and symptoms associated with NAFLD. Being male is considered a NAFLD risk factor and prevalence as great as twice that for women has been reported.[1,2,41] However, there is little consistency in the evidence since other studies show an increased risk for women,[42–44] consistent with our study’s finding that NAFLD was more frequent in women than in men.

When the analysis is adjusted for age, studies reveal NAFLD prevalence and incidence is greater in women after menopause because body fat is redistributed toward the abdomen due to loss of estrogen’s protective effects, a factor that favors appearance of MetS.[43–45]

Although it is known that insulin resistance and obesity are associated with the metabolic alterations characteristic of NAFLD,[46] some studies have reported a relatively high prevalence of NAFLD in lean people, particularly in young women, who are very unlikely to have insulin resistance and hypercholesterolemia and who have a lipid profile that is different from that of overweight or obese individuals. NAFLD frequency in lean patients in our study (9.2%) is less than the 18% reported by Younossi.[47] This is a potential topic for further research.

NAFLD is considered a polygenic disease and an inherited condition involving genetic variants related to disease progression.[48,49] Higher frequencies of NAFLD have been reported in the Hispanic population than in Afro-descendants or indigenous Americans. These differences seem to be associated with genetic variations such as the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 gene (PNPLA-3), which is more frequent in Hispanics. These variations increase the risk of disease progression in persons who do not have metabolic syndrome, regardless of their dietary patterns and metabolic traits.[50] So far, there have been no genetic studies of this type in Cuba and skin color has proven to be unreliable as a proxy for these genetic variations, given the broad admixture in the Cuban population.[51,52]

It has been shown that family history of type 2 DM is closely linked to NAFLD, with a high risk of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (OR: 1.51, 95% CI = 1.01–2.25; p = 0.04) and fibrosis (OR: 1.49, 95% CI = 1.01–2.20; p = 0.04),[13] which may explain the high frequency of type 2 DM in family medical histories of patients with NAFLD. This should be taken into account when conducting population-based studies.

Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed in a proportion of patients that is alarming if we bear in mind that cirrhosis was not the main subject of this investigation. A large proportion of patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis presented frequent metabolic risk factors that, in most cases, suggested undiagnosed non-alcoholic steatohepatitis that developed undetected over time, and also that the diagnosis of cirrhosis was established at advanced stages.[53]

A multicenter study involving several countries, including Cuba, showed that patients with cirrhosis due to NAFLD (indicative of severe fibrosis) suffer complications related to chronic liver failure, while those with less severe fibrosis present with other conditions such as cancer (not liver cancer) and vascular complications.[54] Studies are needed to identify predictors of liver fibrosis and progression to cirrhosis in Cuban NAFLD patients who have conditions characteristic of metabolic syndrome.

It was not possible to assess the reliability of measurements in the NAFLD ultrasound diagnosis, as they were carried out at a single point in time, by a single observer (a radiologist) and in differing clinical scenarios, using dissimilar ultrasound equipment. However, in order to minimize bias, standardized diagnostic criteria for this disease were used,[1] and the examination was carried out by the most highly-skilled radiologist in each center. The fact that 17% of eligible patients with a probable diagnosis of NAFLD were excluded from the study (either because they refused to participate or failed to complete the required information), may represent an underestimation bias of disease frequency. Regions within the country could not be compared and results cannot be generalized to the whole Cuban population, since for practical reasons most participants were recruited in western Cuba. However, outcomes are important as a first approach to the study of this disease in the country.

CONCLUSIONS

The proportion of NAFLD in these Cuban patients coincides with that reported in the wider Caribbean, which has a high frequency of obesity, overweight and sedentary lifestyles. Most NAFLD patients were asymptomatic, female or had metabolic-related comorbidities such as HBP, type 2 DM and dyslipidemia. In addition, type 2 DM and obesity were frequent in these patients’ family medical histories.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Armando Borrego-Rivero and Rosaura Pichs-Brito, both biostatisticians at the Medical Records Department of the Gastroenterology Institute, for their administrative assistance.