INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer continues to be a health problem worldwide, morbidity and mortality rates increasing in recent years. Cuba is seeing a clear upward trend: mortality rates have increased from 22.3/100,000 population in 1970 to 45.3 in 2012.[1,2] There were 5097 deaths from tumors in the trachea, bronchi and lung in 2012, corresponding to a rate of 58.0/100,000 population in men and 32.5 in women.[3]

Globally, many neoplasms are diagnosed at incipient stages using simple tests, but despite extensive efforts, lung cancer diagnosis continues to be delayed. This is of particular concern, since lung carcinoma is still among the tumors with shortest patient survival rates. Although many factors are involved, one of the most important causes is diagnosis at advanced stages, which occurs in a large proportion of lung cancer patients.[4,5] Symptoms tend to appear late, making diagnosis difficult, and up to 80% of patients have inoperable tumors at diagnosis; in only 22% is the disease potentially curable.[6–8]

Havana’s Joaquín Albarrán Clinical-Surgical Teaching Hospital (HDCQ) is a secondary care center offering the major clinical specialties, including internal medicine and pulmonology. This means that, even though it is not a specialized center, it has a large patient population (primarily from the municipalities of La Lisa, Marianao and Playa, accounting for one fifth of Havana’s approximately two million people). Making rational use of available resources early detection of lung cancer and diagnostic confirmation, should be as rapid as possible, so that treatment can begin promptly, especially surgery.[9]

The time from a patient’s first perception of symptoms until disease is diagnosed is known as diagnostic delay. International research on the subject has found an average diagnostic delay for lung cancer of approximately three months, while in Cuba, small-scale studies have estimated delays of three to six months, which experts consider unacceptable.[6,9–15]

Many determinants play a role in diagnostic delay. Generally, they can be divided into delays in the patients’ first seeking health care and delays within the health care system. Patient delay involves several factors, mainly related to the patient’s perception of symptoms, educational level, age and perceived risk, whether symptoms are typical or atypical; and health system factors, such as accessibility, can also play a role.[6] It has been suggested that lung cancer patients wait longer to see a physician than people with other types of cancer, among other reasons, because symptoms are similar to those of various respiratory diseases.[16] Health system delays are influenced by health worker expertise in symptom recognition and by availability and organization of facilities and resources.[17]

Improving prognosis and survival for lung cancer patients depends therefore on determining the components of diagnostic delay and using this information to develop local and national strategies to reduce it. The purpose of this study was to assess lung cancer diagnostic delay in HDCQ from 2007 through 2010, and to identify its various components and the times contributed by each, comparing results to those in the international literature.

METHODS

A retrospective descriptive study was conducted using administrative data from 54 patients, that is, the total number of people with a lung cancer diagnosis confirmed by cytology or biopsy in the HDCQ pathology department from 2007 through 2010. Patients either were referred from a primary care facility or went directly to the hospital. Hospital clinical records were reviewed and the data entered into Microsoft Excel databases.

Variables Data concerning sex and age at time of admission were collected, as well as the level of care of first visit (primary: family doctor-and-nurse office or community polyclinic; secondary: HDCQ—the hospital where the study took place).

Diagnostic delay was defined as time elapsed, in days, from onset of symptoms to confirmation of diagnosisand was divided according to the following components:[11]

- Patient delay: Time elapsed from onset of symptoms until first consultation, independent of level of care

- Primary care delay: time elapsed from patient’s first primary care consultation until seen at the next level of health services

- Secondary care delay: time elapsed from patient admission and/or assessment at the secondary care level until confirmation of diagnosis

Analysis Statistical analysis was performed using InStat version 3.0 software. Absolute frequencies, percentages and SD were calculated and presented in tables.

Ethics Data from medical records were anonymized to protect patient confidentiality. The protocol was approved by the HDCQ ethics committee.

RESULTS

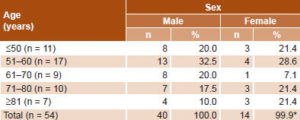

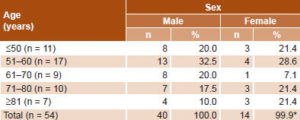

Of the 54 patients studied, the largest group was aged 51–60 years (31.5%; 17/54). Men outnumbered women (74.1% vs. 25.9%) (Table 1).

Table 1: Lung cancer patients by age and sex, HDCQ, 2007–2010 (n = 54)

*rounding error

HDCQ: Joaquín Albarrán Clinical-Surgical Teaching Hospital

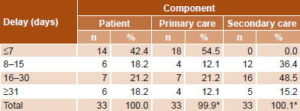

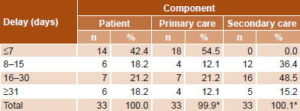

First consultation occurred at the primary care level for 61.1% of patients (33/54). Total delay was 67.4 days for these patients: patient delay 24.3 days (SD 32.8), primary care delay 16.2 days (SD 5.2), and secondary care delay 26.9 days (SD 20.1). Among these patients, diagnostic delay at primary care level was <7 days in 54.5% of cases and secondary-level delay was >16 days in 63.6% of cases (Table 2).

Table 2: Components of lung cancer diagnostic delay in HDCQ patients first seen at primary care level (n = 33)

*rounding error

HDCQ: Joaquín Albarrán Clinical-Surgical Teaching Hospital

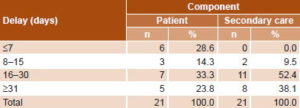

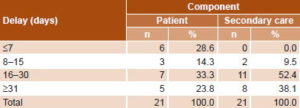

Patients who went directly to the secondary level had a total delay of 79.1 days (SD 81.8): patient delay 47.8 days (SD 25.6) and secondary level delay 31.3 days (SD 14.4). They experienced diagnostic delay >16 days in 90.5% of cases (Table 3). Diagnostic delay >30 days occurred in 74.1% of all cases, and no patients experienced total delay <15 days (Table 4).

Table 3: Components of lung cancer diagnostic delay in HDCQ patients first seen at HDCQ (n = 21)

HDCQ: Joaquín Albarrán Clinical-Surgical Teaching Hospital

Table 4: Total diagnostic delay in HDCQ lung cancer patients (n = 54)

*rounding error

HDCQ: Joaquín Albarrán Clinical-Surgical Teaching Hospital

DISCUSSION

The predominance of men in the study population is consistent with the epidemiology of lung cancer[1–3] and with other reports on diagnostic delay in Cuba.[10,11] Internationally, most patients have their first consultation at the primary care level,[18–20] and this is also the case in Cuba, where there is universal free access to health care, grounded in a national primary care network based on neighborhood family doctor-and-nurse offices and community polyclinics.[20] While service accessibility is a health system characteristic, it influences the patient’s ability and decision to seek attention and therefore affects the temporal lapse between symptoms and first medical contact. Cuba’s extensive network of primary care facilities helps explain the fact that more than half of patients first sought care at the primary level and that those who did so delayed less than 15 days.

Our data suggest that diagnostic delay occurs at each step in the process, although patient delay had the greatest impact for those who went directly to the hospital, even longer than patient plus primary care delay for those who first sought attention at the primary level. Other research outcomes vary concerning which delay component has a greater impact on total diagnostic delay. In Cuba, Borrego found that 61.7% of diagnostic delay was due to patient-related factors,[12] while Valdés found the health system to be the greater contributor (mean delay 61.6 days).[11] Salomaa in Finland found the two components to be approximately equal.[21] The explanation for these differences could be variability in study scenarios. There might be differences in recognition of symptoms, poor assessment of symptoms, or interaction among factors.[6] Our study did not intend to delve into the reasons for delay, but only to understand its composition.

The greater diagnostic delay at the secondary level could be due to a sporadic lack of diagnostic tools for imaging, endoscopy and pathology, or possibly to ineffective organization by HDCQ of available material and human resources, or lack of a suitable lung cancer protocol, such as those in other Cuban hospitals, aimed at reducing diagnostic time to seven days.[22]

The total diagnostic delay we found is considered high. Several studies agree that a total delay greater than 45 days is unacceptable;[23,24] some even suggesting limits of 2–4 weeks, though these recommendations are for the most part empirical.[25,26] Many published studies on this topic find that even the less stringent limits are not met, including Simunovic in Ontario, Canada, in 2000,[27] Myrdal in Sweden 1995–1999 (median delay 4.6 months),[28] Salomaa in Finland in 2001 (mean delay 98 days),[21] and Allgar in England 1999–2000 (mean delay 88.5 days).[15] In Cuba, Cabanes found that 59.4% of patients studied experienced a delay of < 90 days (2003–2009)[29] and Valdés found total diagnostic delay of 73.1 days (2005–2007).[11] Borrego’s 2008 study found that 47.4% of patients waited >12 months.[12]

The similarities between our results and those of other studies, even in more technologically advanced countries, suggest that poor organization and management of health services, not just material shortages, play an important role in diagnostic delay. Several authors recognize this and propose setting up diagnostic assessment units, as has already been done for breast cancer.[30]

One limitation of this study is that it did not include lung cancer stage or histology at diagnosis, which could have an impact on the expression of symptoms and their perception by patient, doctor or both. Another is that we were unable to determine whether and how much patient factors or appointment availability affected delay between referral to secondary care and time seen there.

It is important to recognize which factors have a specific impact on diagnostic delay, because addressing these would have a positive effect on prognosis and survival. We recommend expanding this study to other areas of health care, looking more closely at factors explaining diagnostic delay. We also recommend public campaigns to raise awareness in people at risk of lung cancer, so they can promptly recognize early symptoms and learn about options for diagnosis and treatment.

CONCLUSION

Diagnostic delay in lung cancer is inadmissibly high among HDCQ patients, and those who went directly to the hospital, instead of visiting primary care facilities first, did not benefit from shorter diagnostic delay.