Cuba 1963: a nation grappling with the legacy of inequities between rich and poor, city and country. In 1959, Cuba’s new government inherited a land in which 89% of families in the countryside didn’t have milk to drink,[1] 45% of school-age children didn’t attend school,[2] and the vast majority of families in the remote and mountainous regions had no health care at all.

To top things off, by 1963, the health system was hemorrhaging doctors to the United States. Like ripping a bandage from a wound, Cuba’s brain drain was quick and painful, with some 3,000 of the country’s 6,300 doctors leaving by 1967.[3] In response, the government established the island’s second medical school in eastern Santiago de Cuba, and newly-graduated physicians joined the health ministry to set up the Rural Medical Service. The two initiatives foreshadowed a broader commitment to prioritize human resources for health and to train doctors who would serve where need was greatest, at home or abroad.

On May 23, 1963, a team of 58 Cuban doctors, dentists, nurses, and technicians left for recently-independent Algeria at the request of the new government there. In 13 months, they performed 540 major surgeries in six sites throughout the country.[4] Reflecting on his own experience as one of the volunteers, Dr Roberto Capote noted: “It started with the idea that there was always someone worse off than ourselves and we could share what little we had.”[5]

From Algeria in 1963 to earthquake- devastated China today, attention to the most vulnerable populations has underpinned the country’s health cooperation. “Doctors, nurses, health professionals -they must have the scientific knowledge and specialist training that prepares them to treat even the most complicated cases,” said Cuba’s Health Minister Dr José Ramón Balaguer in his speech commemorating the 45th anniversary of the Algeria effort. “But they also have to be profoundly ethical, with a deep moral resolve to think about others before themselves, treating patients as human beings, with the respect and care they deserve.”[6] Dr Balaguer also underscored the importance of maintaining standards and improving efficiencies within Cuba’s own health system – something coming under increasing scrutiny since national debates in 2007 revealed some patient dissatisfaction.

Over 45 years, Cuba’s health cooperation has evolved into a global clinical, educational and preventive program including a specialist disaster response team, a volunteer global health corps, a full scholarship medical school program, and a sight restoration initiative. Over 130,000 Cuban health professionals have volunteered abroad since 1963.[6] Currently, there are 36,770 Cuban health professionals working in 70 countries under various modalities of cooperation (see Table 1).[7]

Features of Cuba’s international program include:

– staffing public health systems, thus providing low or (more often) no cost services to patients;

– serving in the most remote, underserved areas usually for two years or more;

– building in sustainability by providing medical education opportunities;

– volunteer service by health professionals based on bilateral government agreements; and

– technology transfer.

Table 1: Cuban Health Professionals Serving Abroad, June 2008

*Posts are in United Nations agencies. Source: Vice Ministry for Cooperation, Ministry of Foreign Relations (MINREX), June 3, 2008.

Hurricane Relief Turned Health System Relief

In 1998, Hurricanes Mitch and Georges unleashed their fatal wrath on Central America and the Caribbean, killing over 30,000 and leaving 2.4 million homeless.[8] As in all natural disasters, disproportionate suffering was borne by the poor, infirm, aged, and other vulnerable groups. Cuba was among many countries that mounted relief efforts, sending 1,000 medical personnel to affected areas. The wind and water eventually subsided, but the hurricanes exposed the region’s stark inequalities and precarious health systems. This deadly combination led to launching Cuba’s most ambitious international health programs: the Latin American Medical School (ELAM in Spanish) as part of the broader Comprehensive Health Program (CHP).

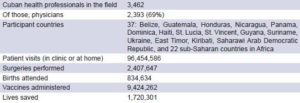

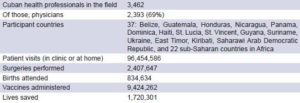

Table 2: Cuba’s Comprehensive Health Program (CHP)

Source: Vice Ministry for Cooperation, MINREX, May 2008.

The Comprehensive Health Program is designed to bolster a country’s public health infrastructure by staffing local clinics and hospitals – usually in remote and underserved areas – with Cuban medical teams. This cooperation is solicited by the host country, in many cases because it cannot entice its own health professionals to work in such isolated or poor regions. Often these Cuban volunteers are the first providers of physician services to rural and indigenous populations.

Since its founding 10 years ago, statistics kept by the Cuban medical teams indicate the CHP’s health professionals have saved 1.7 million lives around the world. Currently, there are some 3,400 Cubans working in the CHP in 37 participating countries (see Table 2).

Clearly, Cubans can’t stay abroad forever, nor are they a long term solution to the human resources crisis facing most developing nations. A more sustainable Cuban contribution emerged in 1999: the Latin American Medical School (ELAM). ELAM’s mission is to train low-income, culturally-connected medical students from the same poor communities where they are encouraged to practice upon graduation. The six-year program, which involves a central basic sciences campus in Havana and extends to Cuba’s 21 medical schools for the clinical years, is a component of the CHP and contributes to Cuba’s goal of training 100,000 doctors for the developing world by 2015.

Interestingly, ‘developing world’ in the ELAM lexicon includes those underserved areas of the United States, whether rural towns or inner cities. Over 100 US students are enrolled at ELAM, and 17 have graduated since 2005, returning home to take licensing exams and pursue residency programs (see Table 3).

ELAM recruits a different kind of student and trains in a non-traditional model, which combines community-engaged population health with strong clinical skills, and prevention with disease management. Additionally, the curriculum takes an integrated, holistic approach that contemplates pathologies in the context of the whole person, and the individual in the context of their family and community.

This ‘preferential option for the poor’ is reinforced in both recruitment and post-graduation service by offering full scholarships in return for students’ non-binding pledge to practice in medically underserved communities. While all the graduates may not fulfill that pledge, early results in some countries are encouraging: in the Honduran Mosquitia, Garífuna graduates and their community built a remote area’s first local hospital, staffed by Cuban physicians and the graduates, now medical residents; and in Guatemala, ELAM-trained doctors are at work in the remote communities of the country’s indigenous highlands. (See Giraldo G. Cuba’s Piece in the Global Workforce Puzzle. MEDICC Review . 2007; Fall 9(1):44-47.)

ELAM II was established in 2006, aimed at expanding physician training. This program follows the same recruitment principles and curriculum. The difference is that ELAM II students are trained at refurbished boarding school sites across the island, now equipped with IT and other teaching aids. The students’ clinical training is carried out at the school’s clinic, and at local community polyclinics and hospitals. Such decentralization has allowed for a massive scaling up: there are currently another 14,000 medical students from 30 countries training under this model.[9] The first class is due to graduate in 2012.

Between ELAM, ELAM II and other bi-lateral education agreements, there are 24,857 international students training to become doctors in Cuba.[7]

Regional Partnerships

The regional barter and social development program known as the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas (ALBA) offers another mechanism to scale up medical education and health care for underserved populations. Currently, full ALBA members Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia collaborate on a range of health programs from sight restoration to diagnostic centers established and staffed by Cuban specialists and local health personnel. Eventually, through various medical education initiatives, local doctors are expected to staff these programs entirely.

Member of ELAM’s first graduating class, 2005.

In Venezuela, Cuban doctors and Venezuelan nurses staff 6,500 community-based primary care clinics located in 335 municipalities – many in remote areas. In a ‘university without walls’ model known as the Comprehensive Community Medicine Program, Cuban physicians are training 21,300 of Venezuela’s future doctors.[9] Additionally, 10,000 nurses are training in a school Cuban professors helped establish , the first due to graduate this year.[10]

Under the ALBA accords, 395 Comprehensive Diagnostic Centers have been established in Venezuela and 28 in Bolivia. These centers serve as teaching sites for medical students enrolled in the ‘university without walls’ program, and provide diagnostic services, including X-ray and ultrasound, endoscopy, hematology, parasitology, urine and other laboratory tests, electrocardiograms and emergency cardiology services, intensive care, and clinical ophthalmology. Additionally, six High Technology Centers have been equipped and staffed in Venezuela to offer a variety of advanced services such as nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, bone density analysis, CAT scans, and mammography.

Henry Reeve surgeons in Pakistan, 2005

Table 3: Latin American Medical School (ELAM)

Source: Vice Ministry for Cooperation, MINREX, May 2008.

In 2004, Cuba and Venezuela launched the vision restoration program known as Operación Milagro (Operation Miracle) for low-income people in the region who suffer from blindness or vision loss due to cataracts and other reversible conditions. [11 ] Originally, patients were flown to Cuba accompanied by a family member, received treatment and surgery at Havana’s Ramón Pando Ferrer Ophthalmology Institute, and were accommodated at a hotel for the immediate recovery and follow-up period. The surgery, related medicines, and logistical costs for the patient and their escort were covered by the Cuban government.

As more countries solicited participation, the program was expanded in number of patients and conditions treated. As of May 2008, the vision restoration program had treated over 1 million people, including 151,805 Cubans (see Table 4). Conditions treated now include cataracts, pterygium, diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, glaucoma, ptosis, strabismus, nyctalopia (night blindness), and retinitis pigmentosa.

Responding to Disasters

Cuba’s most recent initiative in international health cooperation is the Henry Reeve Team of Medical Specialists in Disasters & Epidemics, named after a decorated US soldier in Cuba’s First War of Independence. Established in the wake of Hurricane Katrina to provide emergency medical relief to the Gulf Coast an offer rejected by the US administration the Henry Reeve Team was first dispatched to Guatemala in October 2005 following Hurricane Stan.

Later that month, the team began arriving in Pakistan with 32 fully equipped field hospitals to aid earthquake victims. At the end of its 7-month stint, the team had grown to 2,378 members, including doctors, nurses, physical therapists and technicians, and had provided some 1.7 million patient consultations (See Interview: Cuba’s Man in Sichuan, China). “For us, Pakistan was a school,” says Dr José Jorge Rodríguez, head of the Henry Reeve missions in Peru and China. “That’s where we learned how to tackle the complexities that come with disaster relief.”[12]

Table 5: Selected Cuban International Relief Missions, 1960-2008

Source: MEDICC Review, Aug-Sep 2005; Vice Ministry for Cooperation, MINREX.

Since Pakistan, the Henry Reeve Team has served in the wake of natural disasters in Bolivia, Indonesia, Peru, Mexico, and most recently China, where a donation of 4.5 tons of medicine accompanied the Cuban specialists. The Henry Reeve approach relies on several factors including tailoring the mix of specialists to the type of disaster event and local context; establishing, equipping and staffing field hospitals in remote areas; conducting systematic field visits to inaccessible communities or homes to ensure comprehensive coverage; remaining on-site as long as the affected country requests; making medicine and material donations to affected areas; and working with local authorities and other relief agencies.

This approach has been honed over decades of Cuban disaster relief, beginning in 1960 when a medical team was sent to aid Chilean earthquake victims (see Table 5). The Henry Reeve disaster relief strategy and professionals also benefit from master’s degree programs in disaster medicine; documentation of the specific logistics, personnel and medicine requirements of each mission upon its return; and accumulated in situ knowledge and experience.

Better Health through Cooperation

Disasters and disease transcend national boundaries: climate change and its associated effects, and communicable and vectorborne diseases are global problems requiring innovative, comprehensive and international solutions. The crisis in human resources for health, with multitudes of professionals preferring the cities and private practice either at home or abroad, compounds an already tenuous situation. Cuba’s international cooperation is an example of a multi-faceted response, involving public health systems and communities in need, which has been developed over four decades. Its breadth also provides an opportunity to evaluate models of service and training, and to track the Cuban-trained medical and nursing graduates, particularly their career choices and the impact of those returning to their home countries.

References

- Agrupación Católica Universitaria. Encuesta de los Trabajadores Rurales 1956-1957. Economía y Desarrollo, July-August 1972. 12:198.

- Uriarte, M. Cuba: Social policy at the crossroads: maintaining priorities, transforming practice. An Oxfam America Report [monograph on the Internet]. Boston: Oxfam America;2002 [cited 2008 May 24]. Available from: www.oxfa – mamerica.org/newsandpublications/publications/research_reports/art3670. html.

- Centro Nacional de Información de Ciencias Médicas. Emigración Médica. Havana. 1968.

- Dr Eduardo Llanes Llanes, 45th Anniversary of Cuban health cooperation (commemoration speech); Havana, 26 May 2008.

- Interview with Roberto Capote for the documentary film ¡Salud!, 5 Dec 2004.

- Dr José Ramón Balaguer, 45th Anniversary of Cuban health cooperation (commemoration speech). 26 May 2008.

- Personal communication. Vice Ministry for Cooperation, Ministry of Foreign Relations, Havana. 3 Jun 2008.

- Reed G. Cuba & the global health workforce: health professionals abroad [article on the Internet]. 2006 [cited 2008 Jun 3]. Available from: www.saludthefilm. net/ns/cuba-and-global-health.html.

- Vice Ministry for Cooperation, Ministry of Foreign Relations, Havana. Jun 2008.

- Vice Ministry of Public Health for Medical Education, Havana. Feb 2008.

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Health in the Americas 2007, Volume 1. Washington DC: PAHO; 2007.

- Author interview with Dr José Jorge Rodríguez, Havana. 9 May 2008.