INTRODUCTION

Maternal mortality is considered an important indicator of the health status and socioeconomic level of a country’s population. A mother’s death, however, is more than just a statistic; it is an event that dramatically affects the stability of her family and community.[1–24] In Latin America and the Caribbean, Haiti has the highest maternal mortality rate (630 per 100,000 live births), and Belize, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Paraguay, and Peru, among others, have maternal mortality rates >100 per 100,000 live births. Colombia has a rate of 78; Brazil, 76; Mexico, 62; and Venezuela, 60. The region’s lowest rates are in Argentina (39), Costa Rica (36), and Chile (17). In 2008, maternal mortality in Cuba was 46.5 per 100,000 live births (29.4 from direct and 17.1 from indirect causes).[25] Even though Cuba’s rate is not among the highest, it indicates a pressing problem for the national health system

In recent years, the term “severe maternal morbidity” has been used to refer to complications occurring during pregnancy, delivery, or puerperium that may be life-threatening if not treated with adequate medical care.[2,14,16,20–24] It has been suggested that this category include any woman admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) during pregnancy or puerperium who needs intensive life-saving treatment.[18] Studies of maternal mortality in ICUs in the literature have found widely varying outcomes, depending on level of socioeconomic development in the country where the study was conducted and on the type of patients admitted.[2–4,7,8,10,11,16,23] In a 7-year study of maternal mortality in intensive care at the Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital in Havana, Cuba, which studied all patients admitted to the ICU for different conditions, mortality was 7.4%.[22]

Patients admitted to the ICU may present with numerous life-threatening complications, which may produce the sequential dysfunction of different organs and systems, leading to multiple organ failure (MOF), a syndrome characterized by an unfavorable prognosis and currently considered the main cause of death in ICUs around the world.[1–15,17–19,23,24,26]

In 1977, Eiseman et al. coined the term MOF to describe a syndrome with varying etiological factors involving simultaneous impairment of at least two organ systems.[27] Many papers were subsequently published around the world recognizing MOF as a syndrome involving organs and systems separate from the site of the original condition, with a clinical spectrum ranging from subclinical dysfunction to irreversible failure of the organs involved.

In 1992, the American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (ACCP/SCCM) published currently accepted definitions of infection, sepsis and MOF, establishing the close link among infection, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), sepsis, septic shock, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS).[28–31] MODS was defined as the “presence of altered organ function in an acutely ill patient such that homeostasis cannot be maintained without intervention.” The term MOF was reserved for the most advanced stages of dysfunction. Primary MODS can occur, “as a direct result of a well-defined insult in which organ dysfunction occurs early and can be directly attributable to the insult itself,” while secondary MODS develops as a consequence of the patient’s response to an insult and is identified within the context of SIRS.[28] These definitions were ratified at the International Sepsis Definitions Conference in 2003.[31]

There is still no consensus on diagnostic criteria for MOF, however, although in recent years various systems have been developed for rating organ dysfunction, and using these ratings as tools for prognosis.[26,29–33] The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scale, in particular, rates 6 organ systems on a scale of 0 to 4. A score of ≥3 indicates “organ failure,” and has the worst prognosis on the MODS spectrum. Several studies have shown that the higher the SOFA score, the higher the mortality.[32–37]

There is a dearth of published literature analyzing MOF in obstetric ICU patients. In a study of 74 female patients at University Medical Center in Jacksonville, Florida, Afessa et al. found that although the mortality rate was low (2.7%), all those who died had MOF, diagnosed in 48 patients.[3] In a study of 453 obstetric intensive care admissions in Mumbai, India, Karnad et al. found 21.6% mortality for the entire series with very high mortality in patients diagnosed with MOF.[11] Munnur et al. found high MOF mortality in Indian patients compared to US women admitted to intensive care units in two teaching hospitals in the respective countries.[15]

In Cuba, Fuentes reported that 26.3% of maternal ICU deaths in his study had MOF but without defining the diagnostic criteria.[38] Urbay et al. also reported MOF as an autopsy finding in 27.8% of women who died in ICU but did not consider MOF incidence among survivors.[6]

Considering the need to further analyze MOF in obstetric patients, the objective of this study is to contribute evidence of the problem by characterizing obstetric patients diagnosed with MOF and admitted to the ICU at the Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital in Havana, Cuba, over a 9-year period, 1998–2006.

METHODS

Patients Between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2006, 422 obstetric patients were admitted to the Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital ICU. A total of 58 with a length of stay in the ICU >24 hours and not transferred to another facility were diagnosed with MOF, constituting the study sample.

Hospital The Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital is a 512-bed urban facility in the Boyeros municipality of Havana City Province. It is the referral center for critically ill obstetric patients from Havana City and Havana Provinces and also site of the Hematology and Immunology Institute. The ICU is a 17-bed multi-purpose unit which also receives hematology patients referred from other hospitals.

Type of study This is a descriptive observational study, approved by the Scientific Council and the Research Ethics Committee of the Enrique Cabrera Medical School. Due to the critical condition of the patients admitted to the ICU, written informed consent for inclusion in the study was obtained from each patient’s next-of-kin.

Data collection and processing A data collection form was designed for recording patient information: age, skin color, history of chronic disease (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, hematologic neoplasia, sickle cell disease, chronic hepatitis), and definitive diagnosis recorded in the clinical history summary; status at ICU discharge (alive or deceased); presence of MOF according to study criteria, and causal conditions of MOF. Information on each patient in the ICU was collected daily from the patient’s chart and from discussions by the attending medical team and the patient care committee for critically ill obstetric patients. Each patient’s SOFA and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) scores were recorded daily (Figure 1). MOF was diagnosed when at least two organ systems had SOFA scores >3 at the same time.[16–24]

Figure 1: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) ScaleVariable Points

PaO2 / FiO2: arterial oxygen tension / inspired oxygen fraction (0.21–1.0) MAP: mean arterial pressure GCS: Glasgow Coma Score

Maximum APACHE II and maximum SOFA scores (APACHE II-max and SOFA-max, respectively) during ICU stay were calculated for each patient, as well as the difference between SOFA Day 1 (SOFA-1) and Day 3 (SOFA-3) scores, called SOFAd3−1. Patients were divided into three groups, according to SOFAd3−1 score: <0, =0, or >0.

Information was entered into an EXCEL database and processed using SPSS 13.0 software for Windows. Qualitative variables included clinical data (history of chronic diseases, diagnosed conditions), age groups, SOFAd3−1 group, and discharge status (alive or deceased). Quantitative variables were age, length of ICU stay, and APACHE II and SOFA scores. Totals and percentages were used to summarize qualitative variables, and quantitative variables were expressed using mean values and standard deviation. The chi-square test of independence was used to analyze the relationship between qualitative variables and patient status at discharge. In all cases, a value of p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 58 obstetric patients diagnosed with MOF, 29 died in the ICU (50.0% mortality). There was a slight preponderance of white-skinned patients over non-white patients among the deceased, which was not significant, and mean maternal age was slightly higher. Although the largest number of deaths occurred in the 30–34 year age group (9/16 patients, 56.3%), followed by the 25–29 year age group (6/15 patients, 40.0%), mortality was highest in the 15–19 year age group (5/6 patients, 83.3%), followed by the ≥35 year age group (5/8 patients, 62.5%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics and Discharge Status of Obstetric ICU Patients with MOF

p <0.05 NS: not significant, * x2 = 0.624, p = 0.430 † mean ± standard deviation ‡ x2 = 0.162, p = 0.687 APACHE II-1: Day 1 Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score; APACHE II-max: maximum APACHE II score SOFA-1: Day 1 Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score; SOFA-max: maximum SOFA score Source: Data collection form. Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital, 1998–2006.

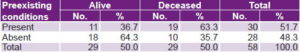

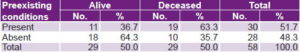

Almost 90% of patients underwent some type of major surgery. Mortality was slightly higher in those without surgery, but this difference was not statistically significant. Day 1 SOFA and Day 1 APACHE II scores, as well as SOFA-max and APACHE II-max scores, mean number of previous pregnancies, and length of ICU stay were all slightly higher in patients who died than in those who survived (Table 1). Mortality was significantly higher, however, in women with a history of chronic disease (63.3%) than in those with no such history (Table 2).

Table 2: Preexisting Chronic Conditions and Discharge Status in Obstetric ICU Patients with MOF

p <0.05 x2 = 4.419, p = 0.036 Source: Data collection form. Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital, 1998–2006.

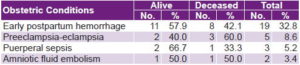

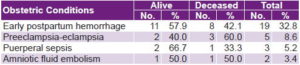

Early postpartum hemorrhage (≤24 hours postpartum) was the most frequent obstetric condition (19/58 patients, 32.8%), followed by preeclampsia-eclampsia (5/58 patients, 8.6%), puerperal sepsis (3/58 patients, 5.2%), and amniotic fluid embolism (2/58 patients, 3.4%). Mortality was highest, however, in patients with preeclampsia-eclampsia (3/5 patients, 60.0%), followed by amniotic fluid embolism (1/2 patients, 50%) (Table 3).

Table 3: Obstetric Conditions and Discharge Status for ICU Patients with MOF

Source: Data collection form. Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital, 1998–2006.

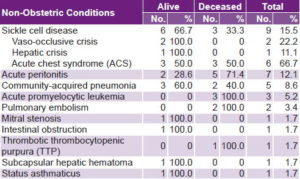

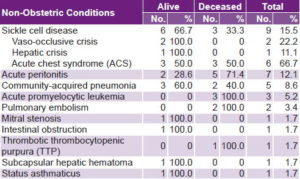

The most frequent non-obstetric conditions were complications of sickle cell disease, which was present in 15.5% of total patients with MOF. Mortality in sickle cell patients was 33.3% (3/9 patients), all from acute chest syndrome (ACS). Acute peritonitis (7/58 patients, 12.1%) and community-acquired pneumonia (5/58 patients, 8.6%) followed in order of frequency, with high mortality among those with acute peritonitis (5/7 patients, 71.4%). Mortality from acute promyelocytic leukemia (3 patients), pulmonary embolism (2 patients), and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (1 patient) was 100% in all cases (Table 4). Two patients discharged alive were diagnosed with both preeclampsia and sickle cell disease with vaso-occlusive crisis.

Table 4: Non-Obstetric Conditions and Discharge Status for ICU Patients with MOF

Source: Data collection form. Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital, 1998–2006.

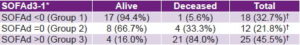

SOFA scores were significantly lower in those discharged alive than in those who died in the ICU, and tended to decline from Day 1 to Day 3, while the scores of those who died tended to increase (Table 5). When the difference between SOFA Day 3 and SOFA Day 1 was <0, prognosis was very good (5.6% mortality). Mortality increased to 33.3% when the score did not change (SOFA = 0); and rose to 84.0% in patients with a score >0 (Table 5).

Table 5: SOFAd3-1 Score and Discharge Status of Obstetric ICU Patients with MOF

p <0.05 * x2 = 27.032, p <0.0001 † Percentage of 55 patients still in the ICU on Day 3 Source: Data collection form. Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital, 1998–2006.

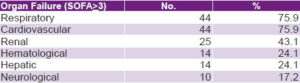

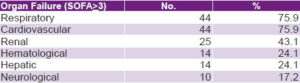

Respiratory and cardiovascular systems were the most affected, followed by the renal system; the central nervous system was the least affected (Table 6).

Table 6: Organ System Impairment in Obstetric ICU Patients with MOF Organ Failure (SOFA>3) No. %

Respiratory 44 75.9 Cardiovascular 44 75.9 Renal 25 43.1 Hematological 14 24.1 Hepatic 14 24.1 Neurological 10 17.2 Source: Data collection form. Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital, 1998–2006.

DISCUSSION

The 29 deaths in patients with MOF included in the present study were the only deaths among the 422 obstetric patients admitted to the Enrique Cabrera hospital ICU in the study period, yielding a 6.9% mortality rate, which is lower than that reported for obstetric ICU patients in the literature.[1,2,4,8,10,11,16,17,24] Only 3 reports of lower rates were found in the literature consulted: 2.7% in Afessa et al.;[3] 4.7% in a 5-year study of post-operative postpartum women by Cheng and Raman;[7] and 0.0% in a recent 2-year study of 34 patients by Muench et al.[23]

Some authors have suggested that prognosis is worse for critically ill obstetric patients in the age extremes—adolescents and women aged >35 years,[2,22] which was corroborated in the present study. Urbay et al. reported a poorer prognosis in women aged <20 years,[6] and Waterstone et al. considered age >35 years an independent predictor of ICU maternal mortality.[2] Bhagwanjee et al., however, found no age-associated differences between patients who lived and those who died.[1]

Association between skin color and discharge status in this study was not significant. In the literature consulted, only Waterstone et al. made reference to “race” as a predictor of severe morbidity and concluded that the worse prognosis for black women compared to white women and other ethnic groups was due to worse socioeconomic conditions.[2]

Higher APACHE II scores for deceased patients compared to survivors reflects the greater severity of illness in the former group, since this system assigns points for the deviation above or below normal for 12 physiological variables, as well as age, existing co-morbidity and relation to surgical status. Numerous studies on maternal mortality in intensive care have used the APACHE II system, omitting points for age, since most obstetric patients are aged <45 years.[1,3,5,7,8,11,14,15,24]

Postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia-eclampsia syndrome are recognized throughout the world as the primary obstetric conditions leading to ICU admission, consistent with results of the present study.[4–8,10–13] Waterstone et al. mention 4 types of severe obstetric morbidity in intensive care closely associated with poor prognosis: severe hemorrhage, severe preeclampsia, severe sepsis, and uterine rupture.[2] In a Nigerian study, Okafor and Aniebue found significantly high case fatality rates in patients with postpartum hemorrhage (50.0%) and preeclampsia-eclampsia (44.0%), outcomes they attributed to poor economic and social conditions manifested in inadequate prenatal care and diet.[10]

In a 9-year study in Cuba, Urbay et al. found that puerperal sepsis was the second most commonly diagnosed condition among obstetric ICU patients (22.5%), almost as frequent as preeclampsia (22.9%).[6] In the present study, however, puerperal sepsis was the third most frequently diagnosed obstetric condition, presenting in only 3 patients, compared to 19 with early postpartum hemorrhage and 5 with preeclampsia-eclampsia. Case fatality rates were highest in patients with preeclampsia-eclampsia, followed by postpartum hemorrhage and puerperal sepsis. Patients with amniotic fluid embolism had a poor prognosis, with death in half the cases, although the number of women with this diagnosis was quite low. However, it is considered a catastrophic condition that occurs during the peripartum period, with a high case fatality rate—over 50.0%—worldwide.[38]

Results of this study are also consistent with literature defining obstetric hemorrhage, preeclampsia-eclampsia, and sepsis as the main causes of MOF in obstetric patients,[3,6,11,15,26] while also showing that many other conditions may play an important role. Other authors have also reported respiratory failure and hemodynamic instability as principal causes.[3,23,24]

History of chronic disease has been recognized as a significant variable in several studies of maternal mortality,[1,2,11,24] and Muench et al. reported an association between chronic diseases and organ damage in 67.6% of obstetric patients admitted to the ICU.[23] Sickle cell disease can cause multiple organ failure or complicate other conditions leading to ICU admission, and there is evidence that pulmonary complications are a determining factor in survival.[39] This is consistent with the relatively high number of patients with sickle cell disease in this study and with mortality in these patients, all of which was attributed to ACS. The characteristics of the ICU, which receives patients referred from the Hematology and Immunology Institute, may also have influenced the number and type of patients admitted.

This study corroborates the validity of dividing obstetric patients with MOF into 3 prognostic groups according to SOFAd3-1 score: clinical improvement (SOFAd <0), no change in status (SOFAd = 0), and no improvement with poor prognosis (SOFAd >0).[37] In the SOFAd = 0 group, mortality was almost 6 times greater than in the SOFAd <0 group, while prognosis was poorest and mortality highest in the SOFAd >0 group.

SOFA is also a descriptor for MODS, enabling both real-time and evolutionary assessment of the insults to organ systems produced by the conditions leading to ICU admission. The systems found to be most affected (respiratory and cardiovascular, followed by the renal system) are consistent with findings in relevant literature.[23,24,27,30,34,35]

The main limitation of this study is that it included only one ICU, the referral center for critically ill obstetric patients for two provinces as well as patients with hematological conditions admitted to the Hematology and Immunology Institute. Findings are therefore limited to this context. Multi-center studies of this type would provide a better characterization of MOF in obstetric ICU patients and more detailed evidence of the factors influencing maternal mortality in Cuba.

Studies analyzing MOF in obstetric patients are urgently needed in order to adopt more effective strategies for reducing maternal mortality in Cuba. Findings of the present study indicate that such strategies should be oriented particularly toward prevention and early treatment of postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia-eclampsia by family doctors and obstetrician-gynecologists providing prenatal and delivery care. Identification of non-obstetric causes of MOF, such as sickle cell disease complications, peritonitis, and community-acquired pneumonia, also demonstrates the need for multidisciplinary, early treatment of these conditions.

Data from this study provides useful information for intensive care specialists by corroborating the importance of using the SOFA organ dysfunction scoring system and estimating prognosis based on the SOFAd3−1 score. Furthermore, showing that the respiratory and cardiovascular organ systems were the most affected highlights the importance of planning resource allocation for mechanical ventilation, cardiovascular monitoring, potent antibiotics and inotropic drugs for these types of patients, as well as application of treatment protocols for each individual condition.