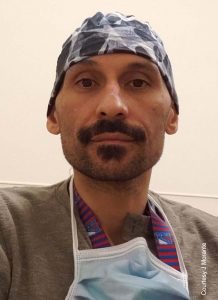

Dr Joaquín Morante, ELAM Class of 2012: Pulmonologist, critical care attending physician at Jacobi Medical Center, New York City.

Speaking remotely with US graduates of Havana’s Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM), I found them at work on hospital floors, in ICUs and health centers across the United States, putting their professional and personal commitment to the test against COVID-19. Nowhere was that more evident than in New York City, the disease’s epicenter, where one grad told me virtually every hospital has at least one MD from the Cuban school, which has provided free 6-year medical training for some 30,000 doctors since the school’s founding in 1999. The student body comes primarily from low- and middle-income countries worldwide, but Cuba also provided 200 US students with scholarships.

One of them is Dr Joaquín Morante (ELAM Class of 2012), who did his medical residency in internal medicine, followed by fellowships in pulmonary disease and critical care medicine. Triple-licensed in internal medicine, pulmonary and critical care medicine, he is now an attending physician on staff at Jacobi Medical Center in The Bronx, one of New York City’s public hospitals, and considered a ‘hot spot’ due to its COVID-19 caseload. I spoke with him during a break at home in mid-April.

MEDICC Review: I think the first question I have to ask is how are you doing?

Joaquín Morante: A bit tired. I worked a 16-hour shift last night, which is how it’s been since COVID-19 started its course through The Bronx and the rest of New York City. In normal times, I wear two hats: I do both inpatient and outpatient medicine as a pulmonologist, and inpatient medicine as an intensivist. So in the intensive care unit (ICU), I usually see patients admitted for a lung issue, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma and so on.

MEDICC Review: What kinds of patients do you see most at Jacobi Medical Center?

Joaquín Morante: Jacobi, a public hospital affiliated with the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, is one of the 11 hospitals under the umbrella of the city’s Health and Hospitals Corporation: we are the public hospitals, a safety-net system. We’re here for the uninsured and there’s no other place for them to go. So we see a disproportionate number of uninsured compared to other hospitals. If you call the city’s health hotline, you’re automatically connected to the public hospital network.

We see people from all walks of life, a wide range of ages, and mainly Black and Latino patients because of where we’re located, and who accesses the public system. Usually, we see the uninsured in an outpatient setting; if you’re uninsured, you’re unable to see an outpatient doctor in one of the private or not-for-profit hospitals since there’s no type of reimbursement for such places, so patients have to pay out of pocket.

But right now, we’re dealing with an inpatient crisis, because people are being told to stay home unless they have shortness of breath. This means that the people we’re seeing are already in respiratory distress, already need supplemental oxygen or some kind of medical support, such as rehydration or antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia.

MEDICC Review: How did your hospital prepare for the influx of COVID-19 patients?

Joaquín Morante: In the beginning of the crisis, in terms of the public hospital network, we started to see the bulk of COVID-19 patients at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens and Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx. Those hospitals quickly reached capacity and had to send their patients to others in the network. Here at Jacobi, our experience was that cases grew exponentially within a week: the first day we had one case, then twice that the next day, then twice that again. We doubled our ICUs from two to four, with the necessary ventilators, nursing staff and places to put these patients who would be admitted to the hospital with respiratory distress syndrome. Because hospital intensive care settings are where the health systems have been stretched to the limit. Normally, most hospitals have one intensive care unit that can handle 12 to 16 patients, and they usually run to capacity. But right now, we have 70 to 100 intubated patients at Jacobi Medical Center. That’s quadruple the number we would normally be handling on ventilators.

MEDICC Review: What are the main challenges you’re facing now?

Joaquín Morante: For us, it’s the volume. We’re seeing a non-stop, steady stream of patients with respiratory distress on the medical floors (who are not ventilated) and in the ICUs, where we manage mostly ventilated patients. We’re filled to capacity. Last night, for example, I personally oversaw 36 ventilations and on top of those, cared for any emergencies for patients admitted to the general medical wards.

MEDICC Review: What does this mean for hospital organization, especially the ICUs?

Joaquín Morante: ICU patients require constant care, so as critical care doctors, our responsibility is to staff the ICU around the clock. There’s always a critical-care attending in-house. During the day, we divide up the ICUs, so that one doctor is directly responsible for one ICU’s patients. We usually work seven days straight, but because we’re so overworked with COVID-19, we switched to a schedule where we work the day shift for five days, followed by two weeks when we work multiple night shifts. So it ends up looking like this: one attending covers days and a rotating staff of ICU doctors cover nights, to make sure that all the patients are safe and their treatment and care plans are executed 24 hours a day.

Of the four ICUs, three are our responsibility, but because we’re spread so thin, trauma surgeons, who are also trained in critical care, are seeing COVID-19 patients admitted in what would normally be a surgical ICU. Since our hospital is a burn center and Level I Trauma Center, the surgeons aren’t accustomed to seeing medical patients, so we end up co-managing those patients to help with the ventilators and medial issues. COVID-19 patients are extraordinarily complicated the world over. We’re seeing a large proportion of these patients going into renal failure and requiring dialysis, going into heart failure—extremely coagulopathic, clotting more than normal. And also developing an inflammatory response, the cytokine storm, that has been deadly for a lot of these patients.

The result is that our ICUs are filled right now, with much sicker patients than usual landing on the general medical floors. We just don’t have the capacity.

MEDICC Review: Do you have enough ventilators and other equipment you need?

Joaquín Morante: I will say—to the credit of New York City—that thus far, we have been able to obtain the ventilators we need; we’ve redistributed. Our 11 hospitals have looked at their capacities and moved ventilators from some of the smaller hospitals that have ventilators that they haven’t needed to the hot spots. To Elmhurst, to Lincoln, to Bellevue, to Jacobi. As of two days ago, in terms of patients admitted to ICU, Lincoln was number one, then Elmhurst, then Bellevue, then Jacobi. Then the rest of the hospitals. So they moved the ventilators to hospitals where there was the surge, seeing a disproportionate number of these critically ill patients.

At Jacobi, we’ve come close to reaching our limit. I’ve had nights where we’ve only had one vent left. But we have not reached the critical point where I’ve been out of ventilators. It’s very scary if you have somebody who needs to be intubated and you don’t have a ventilator to put them on.

MEDICC Review: What about supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE)? And has Jacobi staff been infected with the virus?

Joaquín Morante: The situation in New York City remains dire when it comes to PPE. And we have seen a lot of health care professionals getting sick. Last night, they asked me to come to help with another doctor, an emergency room physician who was symptomatic, with shortness of breath and tachycardia. We’re seeing a lot of our colleagues, including nurses, medical technicians, people who come to clean patients’ rooms, doctors, residents, attendings…we’re all getting sick in very high numbers.

At Jacobi, we definitely don’t have enough of the N95 masks that are so necessary. At this point at my hospital, if you’re in the ICU, you get one N95 mask per day; before COVID-19, you would get an N95 mask anytime you entered a patient’s room. And when you left, you would discard that mask. If you’re on the general medical floors, you get one mask every three days. That’s not enough PPE.

We have always had gloves, but we’ve had issues with getting gowns, face shields and goggles, too. Because of the media coverage about the lack of PPE, we’ve received many donations.

So while we still don’t have enough single-use PPE, as it should be, there has been more PPE available, so it doesn’t have to be re-used by health workers over multiple shifts.

MEDICC Review: I know your partner, Aida Alston is also an ELAM graduate, right now volunteering at Montefiore Hospital here in The Bronx, but also spending most of her time with your two small children. How are you protecting your family?

Joaquín Morante: When it became evident that we were in the middle of a public health crisis here in New York City, I started wearing a mask in the house, to protect Aida and the kids, and started sleeping in a separate bedroom. And I distance myself. In no way do we touch, do we hug or can we be as close as we were four weeks ago. I haven’t seen my father or my mother in weeks, except through video chatting. When they have needed anything, Aida is taking care of it, but we’ve also tried to isolate my parents from the kids, who might be vectors of transmission.

I wear a mask because I could be asymptomatic. As an intensivist, I’m doing procedures with these patients that are considered the highest risk: I’m intubating, which is where you aerosolize their respiratory secretions. That can get into your mucous membranes, into your eyes…you can inhale it. And get infected.

MEDICC Review: Handling such a load of critical COVID-19 patients…are there some who have really gotten to you personally?

Joaquín Morante: I think the whole process has been tough. We’re seeing eight or ten patients dying in one shift. That’s almost a patient an hour on some nights. If you were in a wartime situation and you had a soldier die every hour, you would consider

that to be pretty heavy combat, enormous casualties. To have these patients dying like this takes a tremendous emotional and psychological toll on you. These are people’s grandmothers and grandfathers, mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters. Here in New York, many weeks ago we stopped allowing visitors into the hospital to limit exposure. So these are people who are also dying alone, with no family members next to them to say goodbye. You’re the last person they’re seeing.

Mortality in patients with severe respiratory distress syndrome and who are connected to the ventilators is quite high right now. So from a critical care perspective, although we continue to learn about the disease, we’re not having a tremendous amount of success in extubating these people and getting them better, being able to liberate them from the mechanical ventilators. We’re not seeing constant success with extubation; it has been a very unpredictable disease for the critically ill.

Seeing so many patients requiring oxygen and respiratory support, and at the same time, losing so many…it takes an enormous psychological toll. And while in some ways we were prepared for high mortality with our older patients, anecdotally, I’ve seen 29-year-olds die and 35-, 38-year-olds die from this disease. So it’s not just octogenarians, it’s also your young cousin who has suffered from this disease…and that’s been quite humbling.

MEDICC Review: New York City has been an epicenter of COVID-19 in the United States, and even in the world. What lessons can we draw?

Joaquín Morante: Here in New York City, they’ve just come out with COVID-19 mortality reports by race. They are saying deaths among African Americans and Latinos are the highest and second-highest respectively and African Americans are twice as likely to die from COVID-19 as Whites. The lessons? We already knew the lessons, that Blacks and Latinos are especially vulnerable when it comes to health care. We have the highest rates of chronic disease, not because it’s our fault, but because we don’t have access to health care, we live in food deserts, live on top of each other and in urban environments where disease is easily transmittable. We are less educated, because we have fewer educational opportunities. So these rates are a reminder, a product of this situation, as Malcolm X said, “of the chickens coming home to roost.” Of a health care system that is not set up to take care of people, that’s not set up to take care of poor people, that doesn’t have its values established in taking care of people of color, of taking care of immigrants and taking care of the undocumented. This COVID-19 result is what you get.

Also from an acute public health standpoint, what can we learn? You have to take preventive measures early. This is definitely a disease with high transmissibility, and your health system can be easily overrun in a matter of hours. I remember feeling helpless during the early surge. I think physical distancing and getting people to wear masks, teaching people proper hygiene, about washing their hands, has been very important, crucial. Moves to isolate, quarantine, track contacts of positive cases, and early testing to identify COVID-19-positive patients are all important. We dropped the ball on every single early intervention we could possibly have made. We didn’t have enough tests. We didn’t self-isolate and self-quarantine quickly enough. We didn’t track close contacts of positive cases. We sent positive cases home, without properly tracking those patients.

I think that getting ahead of this and trying to flatten the curve from the very outset is vital. There’s no doubt that this virus is going to circulate once it gets into a community. But flattening the curve from the outset, so that the resources of your health care system are not overtaxed, is so important. And that leads to another point: you have to have a plan in case your system becomes overwhelmed. How are you going to triage these patients; where will you put them; do you have the necessary number of ventilators; do you have the necessary staff to take care of acute patients? And all of that has to be done before you have the possibility of being overrun by the disease.

MEDICC Review: You were trained as a physician in Cuba. Are there experiences or approaches you learned in Cuba that you find useful now?

Joaquín Morante: Cubans are very disciplined and very quick to implement preventive measures and to use all the resources of their health care system to do a number of key things. Number one is education, which was something we lacked here early on. We didn’t do education for the population, telling the public how this disease was transmitted, what were the proper preventive measures to take. We did all of that late, after the horse was out of the barn.

Cubans have always been very good at prevention. Look at dengue, when they had health professionals and medical students knocking on doors, house-to-house, looking for possible sources of vector transmission. We were looking to see if there was standing water in people’s homes; we were giving people the proper insecticide. They’ve always done a good job of saying ‘where can we limit the opportunities for transmission of infections?’ And here, we don’t have that discipline. We have this disjointed system that wants the private sector to do that education. And when it came down to PPE, we left it to the private sector, too. But the private sector is reactionary, not proactive, and so its response is very slow. When you react, it’s already too late. That’s what we’ve seen here in New York.