In 1978, the world was put on notice: health inequalities exacerbated by lack of access to essential services was a ticking time bomb threatening social and economic development everywhere. That year, over 100 countries signed on to the Declaration of Alma-Ata, which affirmed that “health . . . a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, is a fundamental human right.” To guarantee this right, governments were urged to prioritize the provision of quality, continuous, comprehensive and affordable primary care for their entire populations by the year 2000.[1]

Forty years after Alma-Ata, many countries have failed unequivocally to attain that goal. In 2017, the World Bank and WHO released sobering data that nearly half the world’s population was still without essential health services. Meanwhile, the cost of those services—when accessible—had already pushed nearly 100 million people into extreme poverty.[2]

This dire state of affairs is not limited to developing countries. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, the USA will be short 21,000–55,000 primary care physicians by 2032[3] and recent data are not encouraging: the percentage of fourth-year medical students filling primary care positions in the 2019 US National Residency Matching program was the lowest on record.[4] Furthermore, access to a primary care physician for US patients has remained flat—76.4% in 2015 compared to 76.8% in 1996—despite evidence that “access to primary care improves health outcomes and lowers health-care costs.”[5]

From astronomical medical school tuition to inconsistent political will, numerous factors contribute to this global human rights crisis. To forge a plan towards ‘building a healthier world,’ experts and governments were invited to share data, analysis and experiences at the 2019 UN General Assembly’s first High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Among the countries presenting findings is Cuba, a small, developing nation whose health system aimed for universal care and coverage as early as 1960, when the rights to health and education were recognized. Through that decade’s Rural Medical Service, doctors fanned out nationwide to extend health services to all Cubans, reaching universal coverage well before the Alma-Ata Declaration was adopted.

It is now widely recognized that UHC contributes to overall social and economic development. Where health care services are not universal, the most vulnerable and poorest patients are either without care altogether, or often shunted to public facilities—making public health care essentially poor people’s health care. Cuba’s global cooperation policy has been to help staff and strengthen public health institutions and systems in coordination with host governments, primarily in developing countries, rather than “setting up shop” on their own. However, early experiences revealed a daunting challenge: many of these countries’ public systems were dysfunctional, poorly run and sometimes in danger of complete collapse, aggravated in cases of natural disasters or war. Often, the health systems where Cubans served were characterized by crumbling infrastructure, health worker shortages and spatial inequality, financial and material resource scarcity, ineffective or insufficient health surveillance mechanisms, and inconsistent national health protocols. This reality begged the question: could long-term improvements in patient outcomes be achieved in such contexts and might Cuba play a larger role?

The island nation had shown that even poor countries can make significant gains in population health. Today, Cuba’s main health indicators rank alongside those of many high-income countries—despite the challenges of providing universal access at all three levels of health care for 11 million people amidst serious resource scarcities—results that support the island nation’s people-centered strategy emphasizing community-based preventive and primary care.

Since the 1980s, that primary-care foundation was bolstered by vastly increasing the numbers of physicians (from 15,247 in 1980 to 95,487 by 2018). As a result, today some 10,000 family doctors live and practice in the neighborhoods that geographically define their patient load, working with family nurses to provide preventive, curative and rehabilitative care guided by the community polyclinic to which they report and refer.[6] Thirteen health universities dot the country, offering medical, nursing and allied health professional training; some 150 hospitals provide secondary and tertiary care, bolstered by research institutes in 12 specialties and a world-class biotech sector. The country also moved early to strengthen health data collection and analysis, institute national protocols, dedicate more of its GDP to the national health budget (over 11% by 2014); and implement whole-health strategies that prioritize a biopsychosocial approach.[7]

Critical reflection by Cuban health authorities on their own public health practice and its evolution, the knowledge accumulated, and innovative technologies introduced, made the country a natural laboratory for applying and assessing Alma-Ata’s proposals. Furthermore, Cuban training is founded on the principle that health is a right and primary health care a cornerstone of practice—concepts advanced by Alma-Ata that have gained global traction and are now recognized as key to social and economic development. With UHC as a tangible goal for other developing nations, aiming at more effective, sustainable and inclusive health systems that reach the most vulnerable first, Cuba’s experience can offer valuable lessons.

During the past six decades, Cuban doctors, nurses and allied health professionals have worked in public health systems in over 150 countries through bilateral and international cooperation accords; by the end of 2018, more than 400,000 Cuban medical professionals had served abroad.[8] Over time, these programs evolved beyond staffing to include training, technical and epidemiological components, as well as incorporation of pharmaceuticals and targeted specialty-care initiatives.

CUBA GOES GLOBAL: SEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION

Cuban doctors in Asia, the Amazon and Africa: rough, rural, remote.

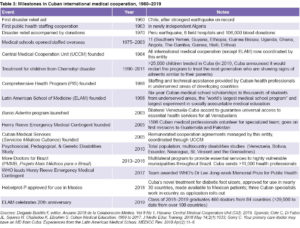

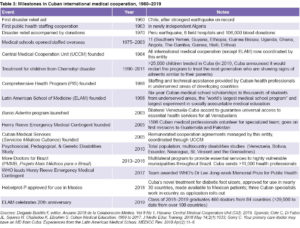

The new revolutionary government of Cuba was still finding its footing when the strongest earthquake on record struck Chile in May 1960. Although the two countries had no diplomatic ties at the time, a Cuban team was dispatched to provide medical services to the thousands injured and two million left homeless—marking the country’s first foray into disaster medical relief. Three years later, at the request of newly-independent Algeria, Cuba sent doctors, dentists and nurses to help staff the gutted public health system, with Cuba’s first bilateral accord in medical cooperation.

These seminal experiences established a framework for structuring effective, sustainable medical cooperation, and also offered important lessons for the future. In Chile, Cuba pioneered solidarity-based medical assistance, providing aid regardless of negligible—or even hostile—government relations with the country in need. Continuity of this approach was revealed following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when Cuba offered 1500 doctors to the Gulf States (refused by former President G.W. Bush). That same year, Cuban postearthquake disaster teams were welcomed by Pakistan’s government, even though Cuba had no diplomatic representation in the country at the time. Algeria solidified a bilateral (and later, multilateral) cooperation strategy whereby the modality and duration of cooperation, type and number of specialists and remuneration, are tailored to the needs of, and in negotiation with, the host country. Often, this includes nonmedical professionals such as engineers, teachers and technicians—a needs-based, mix-and-match model.

TARGETED & TAILORED MEDICAL COOPERATION

As Cuba gained more UHC experience at home—instituting national programs and protocols for maternal–child health, epidemiological surveillance and control, chronic and communicable diseases, older adult health and integrative medicine—it broadened and refined its international commitments. As expanded medical education increased the numbers of health professionals in Cuba itself (after nearly half its physicians emigrated to the USA in the early 1960s), the island extended staffing assistance to over two dozen countries in Central America, the Caribbean, Africa and the Middle East throughout the 1970s.[9] In the 1980s, it began training more doctors with the express purpose of making their services available abroad as well as at home.

- Over time, the principles and practices of Cuba’s international cooperation programs were formalized. These include:

All overseas postings are voluntary;

- In addition to scientific qualifications, professionals serving overseas are expected to conduct themselves according to high standards of ethics and humanistic values;

- Postings are primarily in underserved, including remote, areas for at least two years;

- Cuban personnel staff public facilities offering no- or low-cost services;

- Health professionals are selected for overseas postings from services, locales and institutions with available staff, to avoid causing shortages in the domestic system;

- Composition of international teams depends on needs of host country;

- Participants must successfully complete predeparture training and coursework, including foreign language instruction, emerging and endemic diseases, and history and culture of the country in which they will be serving;

- Local customs and culture will be respected (e.g. women patients are seen only by women physicians in countries where this is customary, collaboration with traditional healers, etc.);

- Professionals working overseas have regular contact with their families in Cuba. In the event of an emergency, all efforts are made to swiftly reunite families;

- Professionals working internationally receive their regular Cuban salary throughout their posting, plus remuneration agreed upon with the host country taking into consideration modality of cooperation, host-country salary levels and in-kind contributions supplied by each party;

- Each volunteer has guaranteed vacations during their posting (timing and frequency depends on length and type of posting); and

- Those who successfully complete international service will be prioritized for future international work depending on their availability and domestic Cuban staffing needs.[8,10]

Cuba’s Henry Reeve Medical Contingent in Pakistan (2005) and joined by this ELAM graduate in postquake Haiti (2010).

Which bilateral/multilateral commitments are considered for inclusion and the enrollment of Cuban volunteers is based on a strategy balancing the needs of Cuba’s health system with the type and amount of help requested. Factors taken into consideration include the kind and number of specialists requested, language capabilities, and possible effects on Cuban health services. In some cases, host-country health authorities participate in choosing from the pool of applicants. Volunteers are solicited throughout Cuba from those health facilities with available staff. “I submitted my name for an international posting after talking to a colleague at one of our weekly polyclinic meetings,” says Dr Eduardo Ojeda, who first served in Indonesia following the 2005 tsunami. “People were suffering and I wanted to make a contribution. I was also interested in learning what international health and medical aid is all about.” Solidarity, broader professional experience plus extra salary mean “there is no shortage of medical personnel volunteering for two-year stints abroad.”[11]

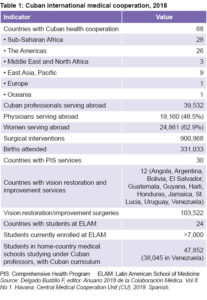

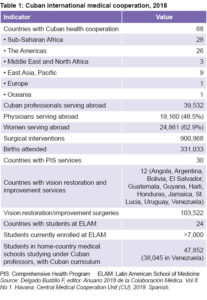

In 1984, the Central Medical Cooperation Unit (UCCM, Unidad Central de Cooperación Médica) was founded to coordinate Cuba’s overseas health commitments. At that time there were 1717 Cuban health professionals serving abroad; today there are more than 39,000 health professionals working in 68 countries in various cooperation modalities (Table 1), plus a small working group in Mexico coordinating application of Heberprot-P, Cuban biotech’s innovative treatment for diabetic foot ulcers. Countries often request several types of medical cooperation, depending on their staffing, technical and training needs.[8]

COOPERATION MODALITIES

Just as the 1960 Chilean earthquake marked Cuba’s entry into international medical cooperation, a duo of natural disasters in 1998 led to a profound evolution of that cooperation. Within weeks of each other that year, Hurricanes Georges and Mitch struck Central America and the Caribbean, killing more than 30,000 and leaving nearly 3 million people homeless. The response to these storms—2 of the deadliest on record—was swift, with Cuba and other countries sending medical teams to the hardest-hit areas in Honduras, Haiti, Nicaragua and Guatemala.

Three realities snapped into focus for Cuban teams providing health services in the wake of Georges and Mitch: 1) vulnerable populations, including the poor, infirm, elderly and children, bear the brunt of natural disasters and are slower to recover mentally, physically and materially; 2) inaccessible or ineffective public health systems collapse during major adverse events (weather-related or otherwise), increasing fatalities and the probability of disease outbreaks; and 3) in many areas, Cuban doctors were the only health professionals people had ever seen, and they would be without medical care once these physicians returned home. These realizations led to innovations designed to increase access, reduce vulnerability and strengthen the affected health systems in a cost-effective manner.

The Comprehensive Health Program (PIS, Programa Integral de Salud) was launched in 1998 to implement this strategy. PIS is long-term, South–South medical cooperation whereby teams of primary care doctors, specialists and other health professionals serve for two years in some of the world’s poorest and most underserved contexts. PIS teams are currently helping staff public health systems in 30 countries, including Haiti, Honduras, Bolivia, Niger, Lesotho, Congo, Chad and Kiribati. Key components include continuing education for participants during their posting, such as degree-conferring courses and annual scientific congresses to present research; epidemiological surveillance to assess main health problems; and Continuous Assessment and Risk Evaluation (CARE) for patients in the areas where Cubans serve. Bilateral agreements are tailored for each situation, but in general, Cuba finances the lion’s share of PIS cooperation, and its health professionals receive (in addition to their regular salary at home) a stipend to cover basic necessities, while the host country provides housing and logistics.

“I came back a better doctor and stronger clinician,” says two-time volunteer Dr Sara Teresa Aldecoa. “I was seeing diseases I had never seen before, ones that don’t occur or were eradicated in Cuba long ago. I saw the benefits of being a family doctor and how comprehensive care mitigates health care silos. I’m extraordinarily proud of this work,” she adds, noting that she is currently preparing for a posting in Algeria.

Cuban medical education in South Africa and the Latin American School of Medicine.

Vision Program The majority of PIS countries also participate in Cuba’s sight restoration and improvement initiative, Operación Milagro, a program providing free examinations and surgery for reversible vision problems. Fifteen years on, the program has restored or improved the vision of more than three million people, most of them poor, who otherwise would not have had access to such life-changing interventions (Table 1).

The Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM, Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina), a six-year medical school offering scholarships to students from underserved areas, initially was designed to provide sustainability to those health systems supported by PIS teams. Founded on the precept that Cuban doctors cannot staff foreign health systems indefinitely and that the ideal provider is a well-trained, homegrown health professional, ELAM was a bold, expensive gamble in socially accountable medical education. This approach is based on providing hands-on learning about social determinants’ effects on health; sharing responsibility for addressing spatial inequalities and delivering equitable, accessible services; going beyond pedagogical innovations to include integration of graduates into local health systems; and anticipating the type, mix and number of health professionals needed, making adjustments as required.[12]

Inaugurated in 1999 with 1900 students, the majority from the countries hardest hit by Hurricanes Mitch and Georges, ELAM enrollment was up to 10,000 students from around the world in 2005, including the USA. In exchange for these scholarships, students make a nonbinding pledge to practice in areas where they are most needed. Upon its 20th anniversary in 2019, ELAM had graduated nearly 30,000 doctors (in addition to those foreign MDs already trained over the years in Cuban medical universities).

From the USA to Ghana, Niger to Nicaragua, international doctors trained in Cuba are making an impact. In remote La Mosquitia, home to the Garífuna (a Honduran ethnic and racial minority subjected to structural barriers to health, education and economic development), ELAM graduates, led by Dr Luther Castillo, built and staff the First Popular Garífuna Hospital. This coastal region was previously without permanent health care services. In Chile, Dr Juan Carlos Reinao, descendent of indigenous Mapuche, returned home after graduating from ELAM to work in a rural health clinic in Renaico, a town of 12,000. Here he plans to launch several programs adapted from Cuban approaches, including establishing an integrated day facility for elders, increasing staffing in his health area, guaranteeing access to essential medicines and launching prevention initiatives to improve community health. Sound ambitious? It is, but not impossible: Dr Reinao was elected mayor of Renaico in 2012.

In Haiti, D r Patrick Dely had to leave his hometown of St. Michel L’Attalaye after primary school to continue his education in the capital—there was no other option closer to home. Since graduating from ELAM, Dr Dely has built a school in St. Michel which educates, feeds and provides primary health care for over 100 students; was the Haitian Director for the CDC’s Field Epidemiology Training Program 2011–2017; and was the only Haitian doctor to work in West Africa fighting Ebola. In 2017, Dr Dely was appointed Director of Hygiene and Epidemiology by Haiti’s Ministry of Public Health.

r Patrick Dely had to leave his hometown of St. Michel L’Attalaye after primary school to continue his education in the capital—there was no other option closer to home. Since graduating from ELAM, Dr Dely has built a school in St. Michel which educates, feeds and provides primary health care for over 100 students; was the Haitian Director for the CDC’s Field Epidemiology Training Program 2011–2017; and was the only Haitian doctor to work in West Africa fighting Ebola. In 2017, Dr Dely was appointed Director of Hygiene and Epidemiology by Haiti’s Ministry of Public Health.

Perhaps the most visible example of ELAM graduates in leading roles are two women who have been appointed ministers of health, in Costa Rica and Bolivia.

Judging from the available data, US ELAM graduates are also living up to their commitment: as of 2019, of the 182 US doctors trained in Cuba, 92 were in residency or practicing after passing their licensing exams, over 90% of them in primary care specialties. Additionally, 75% serve in Health Professional Shortage and/or Medically Underserved Areas, and nearly all work in the public sector with vulnerable communities.[13]

The Henry Reeve Emergency Medical Contingent Almost 700 ELAM students and graduates volunteered to join hundreds of Cuban health professionals as part of the Henry Reeve Emergency Medical Contingent in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Founded in 2005 in response to the increasing threat of natural disasters, this specialized team is trained and equipped to provide emergency medical services in postdisaster scenarios and epidemics. Although Cuba’s offer to send the team to areas in the USA affected by Hurricane Katrina was rejected, these professionals provided emergency medical aid and services that year to Guatemala in the wake of Hurricane Stan and in postquake Pakistan. Since then, the Contingent has provided free postdisaster health services in over 20 countries following earthquakes, mudslides, hurricanes and tsunamis, and during cholera and Ebola outbreaks.

The principles and practices of Cuba’s Henry Reeve Contingent incorporate those outlined above for PIS, plus other strategies designed to strengthen public health systems and primary care access throughout the recovery stage and even after the Contingent leaves. These elements include:

• Team stays long-term, depending on type/volume of services needed and epidemiological situation (in some cases, like Pakistan and Haiti, this can be six months or more);

• Primary care teams do � field visits to remote/underserved areas (including those outside the disaster zone) to provide frontline health services (often the � first doctors these populations have seen);

• People needing urgent or specialist care unavailable in these remote areas are remitted to Cuban � field hospitals and/or the closest appropriate health facility;

• Field hospitals and surplus supplies are donated to the stricken country when the Cuban team withdraws;

• Team works in coordination with local authorities and other relief agencies for more efficient, effective service delivery;

• Multilateral efforts combine Cuban staffing and expertise with material resources from third countries; and

• Teams seek opportunities for collaboration in other areas of population health (e.g. identifying eligible students for ELAM scholarships, forging cooperation in technology transfer, joint pharmaceutical manufacture, etc.).

In Haiti, Mozambique, Guinea, Guatemala and elsewhere that the Henry Reeve Contingent has served, Cuban PIS teams have been among the first responders when disaster strikes. This is because they were already on the ground, serving long term in communities, with valuable working knowledge of local customs and languages. This predisaster presence and the trust built facilitate logistics and communications with health/emergency authorities before the Henry Reeve Contingent arrives. The region affected by the disaster or outbreak may also have ELAM students or graduates, receive technical assistance, or have other health system support from Cuba. These overlapping elements and long-term South–South cooperation contribute to continuous and expanded access to care. (Table 2)

T HE STRATEGY EVOLVES: SOLIDARITY PLUS SUSTAINABILITY

HE STRATEGY EVOLVES: SOLIDARITY PLUS SUSTAINABILITY

Successful, sustainable cooperation is mutually beneficial. In addition to PIS, Cuban professionals help staff public health systems in those nations with the ability to pay for services rendered. This modality, known as remunerated assistance, can take the form of technical, staffing or biotech manufacturing assistance financed by the host country. Part of the funds remunerates the health professionals and technicians working in-country, while half (or more) is retained by Cuba to enhance sustainability of its own universal health system by supplying sorely-needed revenue. In 2018, over 27% of Cuba’s national budget was spent on health and social welfare,[14] which included $6.4 billion pesos/dollars in funds from such remunerated assistance.[15] This revenue has been used to upgrade equipment, repair and build health and social welfare facilities such as nursing homes and senior day care centers, and extend new services nationally.[14] In 2019, Cuban health professionals also received across-the-board salary increases—financed in part by these international agreements. Currently, dozens of countries participate in this cooperation model, including Qatar (Cuban-staffed hospital), East Timor (family doctors in every health center; specialists in six hospitals), Angola (broad staffing of primary care facilities, advisors in public health) and South Africa (professors, family physicians and other specialists throughout the country, concentrated in the eight provinces with greatest spatial inequality).

Evidence suggests that solidarity and sustainability are both strong components of Cuban global health cooperation going forward (Table 3). One example is the response of Cuban doctors and the health system to the 2014 Ebola epidemic that ripped through West Africa, killing thousands and infecting many more, including most local health providers who were exposed. When WHO issued a global call for help, Cuba’s Henry Reeve Contingent answered. After specialized training at Havana’s Pedro Kourí Tropical Medicine Institute (IPK), 256 Cuban health professionals, all volunteers with previous Contingent experience, headed to Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. There, they received another four weeks of in-country training in prevention, protection and treatment protocols, cultural norms and team integration.

Teamwork is essential during such crises, since agencies and providers with little to no experience working together are beholden to strict protocols requiring coordinated action. Dr Jorge Delgado, who headed the Henry Reeve Contingent in Sierra Leone for their seven months there, says his team worked with other volunteers daily, including those from the USA: “we worked shoulder-to-shoulder with US doctors for months fighting Ebola even though our countries still hadn’t normalized relations.” In this and other disaster/epidemic situations, Cuban health professionals have joined those from the country affected, as well as international aid workers from Partners in Health, the International Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders, CARE and even US military personnel.

While the Henry Reeve Contingent is dispatched primarily at the request of governments in postdisaster situations, the Ebola crisis was only the second time teams were contracted through an international agency, and the first where they were directly paid by WHO. Training modules at IPK and in Africa were coordinated, assessed and certified by WHO specialists. Additionally, the organization assumed all responsibility for providers contracted by them who fell ill, said Dr Félix Báez, a Henry Reeve Contingent veteran who was infected with the deadly virus and airlifted to Geneva for treatment. Once healthy, he chose to donate his blood for research and return to Sierra Leone to serve out his posting: “I decided to go back because people need us. Besides, my dad always told me not to be a quitter.”[16] In 2017, WHO awarded the Henry Reeve Contingent its Dr Lee Jong-wook Memorial Prize for Public Health in recognition of its contribution to global health, including their work fighting Ebola in West Africa.

Increasingly, Cuban health professionals have answered the call en masse, not only for disaster relief, but also to help relieve

Primary care: cornerstone of Mais Médicos, PIS and Barrio Adentro.

physician shortages and implement proactive strategies extending UHC to underserved areas. Such was the case with the More Doctors for Brazil program (PMMB, Projeto Mais Médicos para o Brasil), launched in 2013 by Brazil’s national Unified Health System (SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde). The program was designed to provide essential health services to 40% of Brazilians without access to primary care, alleviating the country’s shortfall of 40,000 health professionals, particularly in remote, vulnerable and indigenous regions.[17]

PMMB was not “an end [but] a means to extend universal access and coverage to all Brazilians…a strategy to develop and strengthen primary care services, including training of doctors from those [underserved] communities,” according to WHO/PAHO consultant in Brazil, Dr Carlos Rosales. Although the call for participants was extended to local health professionals first, few responded; then countries with “better health indicators than Brazil,” were invited to join, including Cuba.[17] In year one, a total of 1846 Brazilian physicians and 12,616 foreign physicians from 49 countries participated, including 11,429 Cubans—the latter through a PAHO/SUS/Cuban Ministry of Public Health partnership.[18]

In addition to staffing, Mais Médicos incorporated elements for strengthening infrastructure, increasing medical school enrollment, and requiring new Brazilian medical graduates to pursue primary care specialties. Global public health experts, regional and municipal authorities, and most importantly, the millions of Brazilians accessing these services applauded the program: research reveals 95% of them approved of the responsiveness of the PMMB health professionals.[17–19] Dr Rafael Urquiza went from urban Havana to live and serve in the mountainous village of Espíritu Santo, population 3000, providing integrated care for three years. “I did a health assessment for each individual, resulting in a health snapshot of the whole population. I documented, evaluated and treated chronic disease, pediatric cases, pregnant women, everybody. I did a lot of home visits—it surprised families to have a doctor sitting on their dirt floors having coffee with them, asking them about salt intake, how well they were sleeping. They’d never been cared for like that; I wasn’t on a pedestal; I was like another neighbor.”

Studies analyzing the impact of PMMB found that “service provision by Cuban physicians shows an equal or higher level of quality than that of high-performance professional teams in the country, improvements in the connection and humanization of service provision and reduction in regional inequities. And the ratio of physicians per inhabitant increased.”[19,20] PAHO’s Dr Rosales noted: “The world associates Cuban international health providers with high quality; the Cuban doctors participating in Mais Médicos have provided essential support to Brazil’s most excluded populations.”[17] In fact, in some regions of the Brazilian Amazon, a Cuban doctor was the first health provider residents had seen and in 10% of municipalities, the only physicians were Cuban.[19,20]

Despite these results, the Brazilian Medical Association vilified the presence of foreign doctors, particularly the Cubans. In 2018, far-right presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro described the Cuban physicians as unqualified and imposters, objected to the part of their salaries remitted to Cuba, and threatened to stop honoring the agreement if elected. When he won, the agreement came crashing down. After more than four years of providing primary care to millions, the Cuban doctors (numbering 8471 at the time) were recalled by Cuba’s health ministry. In an about-face on his own rhetoric, the Brazilian president then offered to contract directly any Cuban physicians who decided to stay; international press reports indicate the overwhelming majority returned home. One who did wrote a scathing “open letter to Jair Bolsonaro,” indicating that although he might not always agree with his own government, his grievances with Bolsonaro were far greater: “I accepted the terms of this contract by my own free will. I am aware that with this money, my mother, siblings, nephews, cousins, uncles, neighbors, my whole family is guaranteed health care without paying anything…I ask for respect for my colleagues. I ask respect for my people’s free choice. I ask respect for those who are poor, uneducated. I ask respect for public health. I also ask the gentleman to study what it means to love thy neighbor, and also to study what homeland means, what dignity means, what diplomacy means, what family medicine means, what equality means, what respect for ideas means, what it means to be the president of poor Brazilians and not just the rich and powerful.”[21]

The collapse of Mais Médicos has left an estimated 28 million without access to primary health care services; data shows that six months after the Cuban doctors departed, 3847 public health positions remained vacant in some 3000 municipalities across the country unfilled by a Bolsonaro initiative.[22] This is tragic for the communities without access to primary care, and problematic for the Brazilian government, since universal health care is a right guaranteed by law.

The most comprehensive example of integrating South–South solidarity with sustainability is the regional Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA, Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América), an agreement among Venezuela, Cuba and eight other Caribbean and Latin American countries. Initiated in 2003 between Cuba and Venezuela, these accords are designed to strengthen economic, health, education and cultural cooperation as well as regional integration. The financing of the agreements over the years has been heavily dependent on Venezuelan oil shipments to several of the member states, including Cuba.[23]

Inside the Neighborhood (Barrio Adentro), the first program launched under this collaboration, was designed to “guarantee universal access to essential, comprehensive medical services to all Venezuelans.”

Based on the PIS model and incorporating similar curative, preventive and academic components, including the vision restoration program, it is the largest international medical commitment in Cuba’s portfolio. By December 2018, there were 22,793 Cuban health professionals serving in Venezuela—of these, 6154 were physicians.[8] Since its inception, the scope of Barrio Adentro has broadened to include centers for ophthalmologic services, high-tech diagnostics and laboratory analyses, comprehensive rehabilitation services, and a hospital staffing and modernization program. All Barrio Adentro services are free of charge.

In order to build sustainability into the Barrio Adentro program, the two countries launched an aggressive bilateral medical education program. Using Cuban curriculum taught by Cuban and local medical professors, Venezuela’s National Community Medicine Training Program graduated 2130 new physicians and 4251 family medicine specialists in 2018. An additional 38,045 Venezuelan students are currently studying medicine in their home country, with Cuban professors and curricula (2160 are in postgraduate degree-conferring programs).[8]

CHALLENGES & ROADBLOCKS

In the increasingly complex and often volatile political and economic context of Latin America, the Venezuela–Cuba portion of the ALBA accords has become a target of the US administration. This is just one example of the fact that Cuba’s global health collaboration is neither seamless nor problem-free.

The differen t modalities require significant logistical and human resources, which can stress Cuba’s own universal health system– particularly at the primary care level during certain years. Over time, addressing these challenges has required reorganizing domestic health services. In 2008, when more than 20,000 neighborhood family doctors were serving abroad, primary care was reorganized to strengthen the role of family nurses and polyclinics in service delivery; some neighborhood family doctors’ offices were closed as a result.[24] While this relieved pressure on family doctors, it contributed to patient dissatisfaction related to wait times and accessibility to physicians. Public health authorities responded to this challenge by increasing medical school enrollment. The result has been to ratchet up the number of physicians, now numbering >94,000, with family doctor-and-nurse offices back to their full complement of staff.[6]

t modalities require significant logistical and human resources, which can stress Cuba’s own universal health system– particularly at the primary care level during certain years. Over time, addressing these challenges has required reorganizing domestic health services. In 2008, when more than 20,000 neighborhood family doctors were serving abroad, primary care was reorganized to strengthen the role of family nurses and polyclinics in service delivery; some neighborhood family doctors’ offices were closed as a result.[24] While this relieved pressure on family doctors, it contributed to patient dissatisfaction related to wait times and accessibility to physicians. Public health authorities responded to this challenge by increasing medical school enrollment. The result has been to ratchet up the number of physicians, now numbering >94,000, with family doctor-and-nurse offices back to their full complement of staff.[6]

Still challenging, however, is figuring out the mix of family physicians and those in various specialties, and sorting out who can actually be spared for volunteer postings. It is also a tough balancing act to ensure that 150 hospitals, 450 community polyclinics, 13 medical schools and 12 research institutes are fully staffed, while at the same time, guaranteeing resources for the necessary tools, equipment and medicines to provide quality care. The complex formula is possible in part, based on the hard currency brought in by colleagues serving abroad that, as noted above, both helps guarantee the sustainability of Cuba’s universal health system and at the same time helps health professionals individually, increasing their families’ standard of living. (Due to depressed peso purchasing power since the 1990s, a physician posted abroad can earn some 25 times his or her guaranteed salary back home.)

Low salaries are related to another challenge going forward: like every other developing country, Cuba faces outward migration of its professionals, including health professionals, with an increasingly unstable global economy and tightened US sanctions complicating resource scarcities at home. This, coupled with the fact that many high-income countries do not respect the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, puts Cuba in a particularly vulnerable spot, given the sheer numbers of physicians traveling. In response, while family physicians have no restraints on trips abroad for any reason, specialists in other fields are required to seek health ministry permission for travel. Although permissions may be generally granted, this regulation may be a source of irritation for health professionals.

Cuban programs for training foreign doctors have required adjustments as problems were identified. This includes better preparation for reinsertion to home health systems, certification of Cuban medical degrees and addressing language challenges. Many countries with students at ELAM were not prepared financially or logistically to incorporate these new MDs into their public health systems. Haiti lagged in its commitment to place more than 1000 ELAM graduates in understaffed and underserved areas, for example, until the ELAM chapter of the International Medical Society (headed by Haitian graduate Dr Patrick Dely) and locally elected officials—some of whom also graduated from ELAM—exerted pressure on national authorities to honor that commitment.[25]

In South Africa, multiple adjustments were made to reintegrate graduates and strengthen the efficacy of the program, including three years of supplemental training back home on conditions not found in Cuba (e.g. malaria and mother-to-child HIV transmission), and involving South African deans and universities in selecting students for Cuban scholarships. There, stigma experienced by ELAM graduates upon returning home is another difficulty worth noting, including racial and ethnic barriers compounded by having studied in Cuba.[26]

Reinsertion to home health systems also presented challenges in the USA, where the first graduates struggled to pass the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), the multipart exams all medical graduates are required to pass)—a problem largely overcome by later graduating classes. ELAM graduates have reported difficulties adjusting to medical care in the USA, due to its reliance on high-tech diagnostics; restrictions on patient care related to insurance coverage and costs; the plethora of electronic recordkeeping systems; other administrative duties; and differences in prescription drug options. In short, the Cuban medical curriculum, combined with transitioning from a UHC system to a mixed- or for-profit system, and cultural and language differences can all affect reinsertion into the usually more fragmented systems back home.[27,28]

In many developing countries, returning ELAM graduates also encounter resistance from medical societies that perceive competition from these doctors committed to no- or low-cost health models. This has been a problem in Honduras, Venezuela and elsewhere, and was at the heart of objections to Mais Médicos in Brazil. Nevertheless, these countries have largely failed to entice doctors from their medical societies (many of whom come from the middle upper class) to work in the poor, remote, rural areas where Cuban-trained doctors are committed to serve. In too many cases, instead of forging solutions for integrating the newly graduated ELAM physicians, vulnerable communities are left without health services.

Critics’ old argument of “substandard medical education” in Cuba has not stood the test of time. The evidence base—on the quality of Cuban family doctors and specialists, emergency responders, researchers and professors, as well as ELAM graduates—speaks to the contrary. So does the depth and breadth of international cooperation with, and oversight by, scores of governments and health authorities where Cuban-trained doctors serve. This includes WHO/PAHO, UNICEF and other UN agencies with which Cuban health professionals work, and medical school deans and professors where Cubans teach. Moreover, improved health indicators from Cape Verde to the USA, Brazil to Haiti,[9,29] and increased patient satisfaction—in communities spared disease outbreaks, among mothers getting prenatal checkups, and in rural villages with primary care services for the first time—perhaps provide the most important litmus test of how and how well these health professionals contribute to extending quality health care for all.

CONCLUSIONS

Cuba’s extensive international experience supporting public health systems around the globe, combined with multistakeholder collaborations, has shown that addressing the human rights health crisis requires joint work by different actors, with differing strengths and knowledge, including the people and communities most in need. Identifying problems, innovating solutions and evolving strategies to bolster effectiveness and sustainability is part of the equation. But governments and international aid agencies must demonstrate an unwavering commitment to primary care access and UHC—including apportioning sufficient funds for the effort and putting public health before politics. Reinforcing health systems using a mix of qualified, experienced foreign health service providers and local health professionals, combined with capacity-building of the latter to support sustainability, has been shown to be effective in increasing access to health services, ameliorating spatial inequalities and segmentation, and improving health outcomes. Cuba’s experience over six decades of international cooperation argues for such a multilateral, multidisciplinary evidence-based approach, keeping people–the most vulnerable especially–at the heart of the matter.

References

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September, 1978 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1978 [cited 2019 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf?ua=1

- United Nations [Internet]. New York: United Nations; c2019. UN News Centre. Half the world lacks access to essential health services – UN-backed report; 2017 Dec 13 [cited 2019 Aug 9]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2017/12/half-world-lacks-access-essential-health-services-un-backed-report/

- Association of American Medical Colleges [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges; c2019. Press Releases. New Findings Confirm Predictions on Physician Shortage; 2019 Apr 23 [cited 2019 Aug 9]; [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/2019-workforce-projections-update/

- Knight V. America to face a shortage of primary care physicians within a decade or so. Washington Post [Internet]. 2019 Jul 15 [cited 2019 Aug 9];Health:[about 3 p.]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/america-to-face-a-shortage-of-primary-care-physicians-within-a-decade-or-so/2019/07/12/0cf144d0-a27d-11e9-bd56-eac6bb02d01d_story.html

- Prioritising primary care in the USA. Lancet. 2019 Jul 27;394(10195):273.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU). Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2018. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 27]. 206 p. Available from: http://files.sld.cu/bvscuba/files/2019/04/Anuario-Electrónico-Español-2018-ed-2019.pdf. Spanish.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; c2019. Countries. Cuba; [cited 2019 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/countries/cub/en/

- Delgado Bustillo F, editor. Anuario 2018 de la Colaboración Médica. Vol 8 No 1. Havana: Central Medical Cooperation Unit (CU); 2019. Spanish.

- Cole C, Di Fabio JL, Squires N, Chalkidou K, Ebrahim S. Cuban Medical Education: 1959 to 2017. J Medic Educ Training. 2018 May 14;2(1):1033.

- Gorry C. Cuban Health Cooperation Turns 45. MEDICC Rev. 2008 Jul;10(3):44–7.

- Blue SA. Cuban medical internationalism: domestic and international impacts. J Latin Am Geography. Univ of Texas Press. 2010;9(1):31–49.

- Boelen C. Social accountability: medical education’s boldest challenge. MEDICC Rev. 2008 Oct;10(4):52.

- MEDICC [Internet]. Oakland: Medical Education & Cooperation with Cuba (MEDICC); c2019. Accumulated data, MD Pipeline to Community Service; 2010 Apr [cited 2019 Jul]. Available from: http://medicc.org/ns/md-pipeline-to-community-service-one-students-dream/

- Puebla Fuentes T. El sistema de salud y la industria biofarmacéutica en Cuba a las puertas de 2019. CubaDebate [Internet]. 2018 Dec 25 [cited 2019 Aug 27];Noticias:[about 8 screens]. Available from: http://www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2018/12/25/el-sistema-de-salud-y-la-industria-biofarmaceutica-en-cuba-a-las-puertas-de-2019/. Spanish.

- National Statistics Bureau (CU). Anuario Estadístico de Cuba, 2018 [Internet]. Havana: National Statistics Bureau (CU); 2018 [cited 2019 Aug 27]. Chapter 8, Sector Externo. Available from: http://www.one.cu/aec2018/08%20Sector%20Externo.pdf. Spanish.

- Reed G. Meet Cuban Ebola fighters: interview with Félix Báez and Jorge Pérez. A MEDICC Review Exclusive. MEDICC Rev [Internet]. 2015 Jan [cited 2019 Aug 14];17(1):6–10. Available from: http://mediccreview.org/meet-cuban -ebola-fighters-interview-with-felix-baez-and-jorge-perez.-a-medicc-review-exclusive/

- Rendón Portelles T. Dr Carlos Rosales: “Mais Médicos se ha convertido en una marca del desarollo de la salud”. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2017 Jul 3 [cited 2019 Aug 15]. 6 p. Available from: https://www.paho.org/cub/index.php?option=com_docman&view=document&slug=mais-medicos-se-ha-convertido-en-una-marca-del-desarrollo-de-la-salud&layout=default&alias=1571-mais-medicos-se-ha-convertido-en-una-marca-del-desarrollo-de-la-salud&category_slug=entrevistas&Itemid=226. Spanish.

- Ministry of Health (BR). Apresentação de um ano do Programa Mais Médicos [Internet]. Brasília (DF): Ministry of Health (BR); 2014 [cited 2019 Aug 27]. 27 p. Available from: http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2014/setembro/04/apresentacao-COLETIVA-1-ANO-MAIS-M–DICOS—04-09-1.pdf. Portuguese.

- World Health Organization. Brazil. The Mais Médicos Programme. Country Case Studies on Primary Health Care [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2019 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/case-studies/brazil.pdf

- Thousands of Cuban doctors leave Brazil after Bolsonaro’s win. The Guardian [Internet]. 2018 Nov 23 [cited 2019 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/nov/23/brazil-fears-it-cant-fill-abrupt-vacancies-after-cuban-doctors-withdraw

- González Infante Y. Carta abierta de un médico cubano a Jair Bolsonaro [Internet]. Havana: Cubadebate; 2018 Nov 19 [cited 2019 Aug 27]. Available from: http://www.cubadebate.cu/especiales/2018/11/19/carta-abierta-de-un-medico-cubano-a-jair-bolsonaro/#.XWguuXlukdV. Spanish.

- Darlington S, Casado L. Brazil fails to replace Cuban doctors, hurting health care of 28 million. New York Times. 2019 Jun 11.

- International Press Service (IPS) [Internet]. Rome: International Press Service; c2019. Development and Aid. Energy. Dependent on Venezuela’s Oil Diplomacy; 2013 Mar 18 [cited 2019 Aug 27]; [about 3 p.]. Available from: http://www.ipsnews.net/2013/03/several-countries-depend-on-venezuelas-oil-diplomacy/

- Reed G. Cuba’s primary care revolution: 30 years on. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 May;86(5):327–9.

- Interview with Dr Patrick Dely, 2019 Jul 26.

- Sui X, Reddy P, Nyembezi A, Naidoo P, Chalkidou K, Squires N, et al. Cuban medical training for South African students: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2019 Jun 17 [cited 2019 Aug 17];19(1):216. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1661-4

- Programs designed to help these graduates successfully integrate back home has resulted in 88% passing rate on the USMLEs; support via mentoring and residency match support improve medical and cultural adjustment.

- Gorry C. Your primary care doctor may have an MD from Cuba: Experiences from the Latin American Medical School. MEDICC Rev. 2018 Apr;20(2):11–6.

- De Vos P, De Ceukelaire W, Bonet M, Van der Stuyft P. Cuba’s international cooperation in health: an overview. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37(4):761–76.

Editors’ note: Senior Editor Conner Gorry is the only foreign correspondent to report from inside the Henry Reeve Emergency Medical Contingent, traveling and living with the teams in Pakistan and Haiti.

Photos: C. Gorry, E. Añé, G. Reed, PAHO