INTRODUCTION

In 2013, the USA received 69,909 refugees identified by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR).[1,2] The top countries of origin listed in decreasing frequency were: Iraq (27.9%), Myanmar (formerly known as Burma, 23.3%), Bhutan (13.1%) and Somalia (10.9%).[2] In 2012, North Carolina ranked in the top ten US states receiving refugees.[3] Guilford County in central North Carolina is estimated to house over 60,000 refugees and immigrants, with more than 120 languages spoken and 140 countries of origin represented in the local school system.[4] This is of particular concern as newcomer populations arrive with a wide range of unique health and nutrition needs.

Factors influencing refugee health are complex and include conditions and risks from both the country of origin and those faced in the host country (i.e., camp settings) after fleeing their homeland prior to arrival in the USA.[5] Refugees often suffer from unmanaged acute and chronic conditions, micronutrient deficiencies and mental health issues.[5] Refugee resettlement in the USA remains steady (e.g., 69,909 in 2013, 58,179 in 2012, 56,384 in 2011), health care systems facing an increasingly diverse population composition with unique health needs.[2] Despite continuing annual resettlement of new arrivals, research and resources for refugee health and nutrition remain limited. This is of particular importance because refugee populations are at high risk for health disparities. Improved health for these populations falls within the priority objectives of Healthy People 2020, which aims to eliminate health disparities and ensure health care access for all people.[6]

Formidable barriers exist in design and implementation of research with refugee populations due to their unique experiences, vulnerability, and language and cultural differences.[7] Many major populations resettling in the USA remain understudied, despite their high numbers. The objective of this study was to examine the environmental, nutrition and health barriers and needs of refugees (defined by UNHCR) resettled in Guilford County, as perceived by individuals providing services to them.

METHODS

Setting The study site, Guilford County, North Carolina, includes the cities of Greensboro and High Point. Guilford County received the highest number of refugees for the state in 2000.[4] In response to the influx of refugees, local community-based organizations were founded, including the Center for New North Carolinians, the New Arrivals Institute, and specialized educational programs.

Study design and development A semistructured guide was developed specifically for this project, its content validated by five experts in the field of refugee health. The guide (Table 1) contained three main sections. The first focused on general information regarding participants’ experience with refugee groups (i.e., position description, length of experience, frequency of interaction with refugees). The second centered on service providers’ perceptions of refugees’ housing and environmental conditions, as well as barriers, concerns and needs related to health and nutrition. Question 12 in the second section was asked for each refugee group with which participants reported regular and frequent interactions. The third section included questions regarding community access and gatekeepers (information not analyzed in this article).

Sampling and recruitment Most contacts were identified through an Internet search including: local resettlement agencies; community health clinics; Guilford County Health Department; Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants and Children; schools; and community or faith-based groups providing refugee assistance. A website with an index of local refugee service providers was also utilized. Some contacts were made via snowball recruitment. Participants were service providers who had frequent (daily or weekly) and regular interactions (paid and/or volunteer) with local refugees, as defined by UNHCR.[1] They were contacted though public email and/or by telephone. Only one individual contacted refused to participate; the final number interviewed was 40.

Table 1: Interview guide

Data collection Between May and December 2013, interviews were conducted at sites preferred by participants, with most choosing their workplace or a public coffee shop. Recruitment continued until no new themes were reported (theme saturation). Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis Participants were assigned an anonymous code (e.g., “CW1”) for each transcription. Deductive content analysis was used to interpret transcriptions as described by Elo and Kyngäs.[8] Categories were created based on the focus of the interview guide including: environment, health (conditions, quality/access of care), and nutrition. Each transcript file was initially reviewed to identify quotes and stories within the category (i.e., health, nutrition or housing). Each category file was reviewed twice by the first author and sections related to the category were identified and summarized into subthemes. Subthemes were grouped into larger themes; for example reported incidences of type 2 diabetes and hypertension were subthemes within the theme of “health conditions.” Lastly, frequency of reporting of subthemes was classified: low (LF, 10–25% of participant responses), consistent (C, 25–60% of responses), and high (HF, >60% of responses).

Ethics The study was approved by the University of North Carolina at Greensboro’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were provided an explanation of how their confidentiality and personal information would be protected in any future publication (e.g., any direct quotes would be listed with codes rather than names, employers or other descriptors) and written informed consent was obtained prior to all interviews.

RESULTS

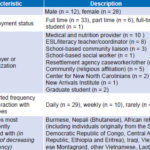

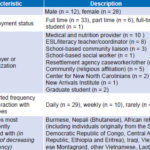

Demographics Participants (n = 40) included 28 women and 12 men from a range of positions. Most worked with refugee groups daily or weekly (29 and 10, respectively). Four participants were former refugees. Participants reported the most interaction and experiences with (in order of decreasing frequency) refugees from: Myanmar, Bhutan, various African countries (including those from the Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Ethiopia and Eritrea) Iraq, Vietnam (including Montagnards) and Laos (Table 2).

Table 2: Participant description (n = 40)

ESL: English as a second language

*Participant who reported rarely was referring to current interactions (had been promoted to clinical management position); previous interactions (service provisions) were described as regular.

Housing and environment Several housing-related themes emerged, including: housing conditions and community descriptions; factors influencing initial resettlement location; and factors influencing movement from initial resettlement location (Table 3). Refugees’ housing conditions were consistently reported as suboptimal, due to poor physical conditions and/or location in low-income and/or dangerous areas.

CW18: They don’t feel like these lower income neighborhoods are safe and I can’t necessarily refute that . . . You hear clients talking about hearing gunshots at night, which terrifies them because that’s what they ran away from.

CW28: Every time I come out of their house I’m thinking “Really? Is this better than where they came from?” because there are cockroaches and, you know, lice, and no furniture . . .

Initial housing placement was reported to be influenced by economic constraints (lack of funding and housing options) and also preference to be close to their own cultural or ethnic group as a source of support.

CW4: Part of it is because it’s really challenging to find affordable three-bedroom housing and the other reason is that . . . the refugee(s) will [eventually] get and have a social security number and get a social security card after they arrive . . . Some apartment complexes want the social security number up front in order to do a background check, but the refugees don’t have that, they get them later, so there’s this balance between the apartment complexes having to be willing to work with the resettlement agency.

Consistent factors that influenced refugees’ decision to move from their initial placement included options for improved housing (usually associated with economic improvement) or a decision to stay because of a strong sense of community and/or community benefits; e.g., English support and a tutoring center at one resettlement site. Those who did relocate tended to move to better housing, to be near other families or members of their community, or into public housing.

CW18: The groups form communities there so it becomes to them their safe place, their village, their home. Some of them do have perks where they can get homework help for their kids and they can get English classes there, and it just becomes something where it may not be where they ideally want to live but they do see the benefits.

CW4: If they move within the first year, they often move out because they want to be closer to other family [members].

Nutrition This theme was divided into five subthemes including: diet trends, access to religious/cultural foods, growing food/gardening, knowledge, and navigation skills for shopping for and purchasing food (e.g., getting to stores, finding products, figuring out how to pay) (Table 3). Dietary trends consistently observed included rapid dietary acculturation, with youth changing the fastest. Consumption of sugary or junk foods was reported with high frequency and some alcohol abuse was reported (less frequently).

CW10: One of the big issues that they have, one of the questions that I get a lot is when the kids get . . . a little older or school age, parents will often say ‘he only wants to eat American food.’

CW18: When I see the kids and I see what the mothers bring the kids I . . . know that that’s not what they would have given their child when they were overseas.

CW12: A lot of pop or soda is being consumed by little kids; they always seem to have a soda with them at some of the sites . . . They’re eating candy and chips and soda.

Lack of variety or quality in the diet was reported. Household risks such as hoarding, poor budgeting skills and perceived food insecurity were consistently reported.

CW3: I’m not sure—often due to pride and things like that—if these families really have plenty of food.

CW16: So, occasionally, if they didn’t fill out the paperwork correctly and the food stamps stop, they will go without food unless somebody tells us.

CW34: Some people fear not having enough, so they’ll hoard the money on a food stamp card. And then I’ll go to the home and see there’s no food and the kids are complaining there’s no food, and then when I ask the parents how much money is on the card, there might be like $2000 on there and they’re not buying food.

Table 3: Content analysis summary

*This was a specific word choice of participants in describing diets of refugees. More frequently, the specifics of the diet like a preference for fresh foods and whole foods were described and “preference for fresh foods” is listed as a consistent theme.

Despite these challenges, refugees were consistently perceived as having a preference for fresh foods, particularly produce, and were reported (less frequently) as having “healthy” diets.

CW14: I would say their desire is to have fresh . . . So I’ve seen [in] the dead of winter . . . [people] buy those grapes for ten bucks a pound, but they want that.

CW28: I have been with my kids [those I work with] and when they do eat lunch they eat everything on the plate, like down to the seeds on the apple. And they are more likely to eat the fruit.

CW31: They go to the garden and get the things and cook, that’s their habit; and they don’t have [a] refrigerator and freezer in their home back home.

Access to culturally-familiar foods was perceived to be good. US supermarkets were the least frequently used, with an international grocery store being the most consistently reported. Several barriers were reported to accessing religious or culturally-familiar foods including: cost, inability to use food stamps at a store (some stores were cash only), unavailability of specific products, and transportation constraints.

CW10: Yeah, language and access to the traditional foods, and access to healthy food, period, because really where they are settled is often a food desert, let’s be honest. Let me tell you, the area around where our clinic [is], it’s Food Lion and then a bunch of dollar stores, and that’s kinda it. And Food Lion is not a traditional food market.

CW18: Some of the Muslim families, they can eat Halal meat but to go to an Islamic grocery store to do it, they’re paying two, three, four, five—I’ve even seen in some cases—ten times the amount of money.

Refugee use of green space to grow fresh food(s) was consistently reported, with home gardens and community gardens the most frequently identified. Service providers reported that refugee groups possessed strong agricultural skills and knew the social and mental benefits of gardening, yet there was a need for more green space.

CW1: They have a lot of techniques to [do] agriculture that we don’t necessarily know here in the USA, so it’s like they’re learning from us and we’re learning massive amounts from them.

CW31: First priority when they buy the house, they look at . . . how much, how big the back yard is . . . because they want to garden.

CW41: A lot of these folks are incredible gardeners and you know you need to give them the place to do that so they can give themselves healthy foods.

Many barriers to using green space were also consistently reported, including hours of operation for community gardens, transportation to community gardens, and limited housing support for using space in apartment complexes.

CW2: They like to plant gardens and . . . city ordinances limit that. You know we only have certain places that you can grow gardens.

CW18: There are several community gardens and the clients do like that, but community gardens are not necessarily close to their apartments.

CW34: A couple of the management groups have allowed people to do community gardens and it helps a little bit, but I wouldn’t say it’s enough, and then we still have quite a few communities that don’t have access to these community gardens.

A variety of nutrition knowledge deficits and navigation barriers were reported; however, no specific concerns were consistently reported. Subthemes included concerns, misperceptions and lack of knowledge about infant formula, other food products (including unfamiliarity with “American foods”), food safety and labeling, and difficulty navigating the food environment in general.

CW40: Being able to read a nutrition label involves knowing what, you know what these things mean, it involves being able to do math, and . . . a lot of refugees didn’t have much school back home.

CW27: As far as the challenges, I’ve been in line in front and behind someone and they’re trying to use their EBT card [Electronic Benefits Transfer card, from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—Eds.] and they’re . . . not sure what to press or where to swipe, or what to do with it . . . I see that for them, [it’s] not so much in selecting food per say, but it’s “the process.”

CW23: I think eating junk food—particularly chips and soda—is a point of pride culturally . . . coming here and having access to Coke all the time.

CW1: They’ve already been treated [for diabetes] . . . It’s like they gave them a pill to manage it but they weren’t taught about diet. So you know they’re still eating the same things, drinking massive amounts of soda and sweet drinks, and taking this medicine and expecting things to get different.

Health This theme was divided into three major subthemes, including observed conditions, barriers to accessing health care (e.g., lack of insurance, transportation barriers) and barriers to obtaining quality medical care (e.g., lack of translation services during visit) (Table 3). The most consistently reported medical conditions were chronic diseases such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes and weight problems (over or underweight). Dental concerns were also described (less often).

CW1: They tend to come with diabetes, high blood pressure.

CW41: There were a number with high cholesterol and hypertension, and again I don’t know how much of it was their change in lifestyles coming here, or that they just never got the care where they were, [sometimes as much as] 20 years in a camp.

CW34: Dental needs are through the roof. If I walk you through some classrooms and I ask kids to just open their mouths, you immediately see a whole bunch of decayed teeth.

Mental health problems were also reported (but less frequently), with concerns about recent experiences with violence by some groups.

CW4: All of the families have varying degrees of mental health [issues] but I think the Sudanese who are coming as refugees potentially have more mental health issues . . . The violence within those countries is a lot more recent.

CW34: Mental health needs, there is a lot of symptoms of post-traumatic stress among our students and their parents. But there is a huge stigma [around the issue of] psychological services for many cultures. And so when I gently and sensitively talk about those topics with people, they usually don’t want to participate at all with any kind of therapy.

CW9: There are a large number of Iraqi refugees who have served in various ways . . . with the military efforts, so a lot of what they’re coming with is very similar to what US veterans coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan are dealing with.

Barriers to accessing health care consistently included difficulty navigating the system as well as Medicaid challenges (e.g., short duration of initial coverage, only eight months). Other barriers included the cost of services and lack of insurance, transportation difficulties, and limited primary care options.

CW2: Time. They have a limited amount of time they have a Medicaid card and it’s so hard to get appointments in a timely manner. Especially if they have chronic . . . health problems. Initially, we can get them into the refugee clinics, and if they have some followup, we can do that, but if it’s a chronic [condition] and surgery, [for] those kinds of things, it takes time.

CW15: Transportation itself in the community with the buses is a whole other story, getting to the appointment itself.

CW23: It is an understanding of where do I go when I have this particular problem, particularly for clients who are using Medicaid—that’s confusing. Well, who is going to take Medicaid, and fewer and fewer providers are even accepting Medicaid.

Lastly, culture and language were individually reported as major barriers to obtaining quality care.

CW18: Yes, but cultural [barriers] happen in that what the doctors may be telling them . . . culturally [it] is completely foreign to them, or the client will leave something out because it is not something that they necessarily think is important.

CW10: If I’m trying to follow evidence-based guidelines for treatment of depression for example. That involves medication, which I can manage, but it also involves counseling which—with a child that speaks Swahili—tough luck.

CW37: What was happening every time she would get an attack or episode, she may go to the doctor or the ER but they weren’t doing a really good job of looking back and forth at who had prescribed what . . . This little girl had four different medicines and she happened to bring [them] in. And if the school nurse and I had not looked at them she was like going to take all four, and if she would have, they would have killed her.

Some also reported medical staff as a concern, but less frequently.

CW31: . . . while they [hospital and clinic workers] are dealing with the refugees, they get frustrated you know, and express their anger.

DISCUSSION

Despite strong evidence of the role of environmental factors on health, few studies have looked at the resettlement environment. In our study, we found that initial placement of refugees was constrained due to limited housing options and management inflexibility or disinterest in partnering with resettlement agencies.

Resettled locations were described as older apartment complexes in low-income areas with reports of refugee concerns about safety. Perception of an individual’s community as unsafe has been associated with reduced physical activity.[9,10] Low physical activity levels and increasing trends of overweight and chronic conditions among refugees have been reported in other studies.[11–20] Despite concerns expressed about safety and housing conditions, the support and strength of the communities were perceived as factors that reduced migration away from initial resettlement locations. This sense of community was also described as a facilitator in relocation patterns, with multiple families moving simultaneously to maintain community or to be closer to relatives or their own ethnic/national groups.

Providers reported barriers (e.g., transportation) to accessing and consuming both healthy and culturally-familiar foods. Resettlement guidelines place refugees near grocery stores and public transportation; however, these stores are often not appropriate for the cultural or religious food preferences and practices of many groups. Additionally, availability of public transportation in the study’s two major cities is limited, compared to larger metropolitan areas. Other barriers to traditional foods included limited availability or inability to use food stamps at some stores. Many groups were reported to prefer fresh produce or foods, or to grow their own food through the use of a personal or community gardens, but such options were limited due to transportation barriers and management restrictions on use of housing-complex green spaces. The high prevalence of food insecurity cited in other studies[21–25] and the preferences and skills to grow and eat fresh foods reported here may support the need for improvements to ensure access to green spaces for refugees resettled in US urban environments.

Increasing access to green spaces and fresh foods might reduce negative dietary trends reported across groups. The poor dietary habits (particularly sodas and junk food) observed by these service providers have also been observed in other studies.[12–15,26–28] Concerns regarding rapid dietary acculturation (particularly in youth), consistently reported here, have been observed in other studies.[12–15,22,26–28] Perceived food insecurity, difficulty budgeting (e.g., running out of food stamps) and hoarding (not spending allocated food-stamp money) were consistently reported as other risks. In addition, the reported high frequency of barriers to navigating the local food environment is particularly relevant, since poor navigation skills have been associated with increased risk of food insecurity in other studies.[21–24]

Reported environmental and dietary risks in this study may increase chronic disease risk and poor health outcomes and in fact overlap with reports—consistent across groups—of chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension and weight problems (over or under weight). Prevalence and concerns regarding mental health needs of refugees have been reported in several other studies in the USA and elsewhere.[29–32]

Added to these problems were many perceived barriers to accessing health services and obtaining quality health care. Difficulty navigating the system and Medicaid limitations (short duration of initial Medicaid coverage; limited access to medical providers accepting Medicaid) were consistently reported as major barriers. The reported lack of transportation, of insurance (and/or high cost of services) and of affordable primary care becomes even more poignant when coupled with the fact that the community clinic serving almost all refugee patients closed during the study period. Barriers to obtaining quality care consistently included barriers of language, culture and medical staff attitudes. Resources such as help lines were often perceived as ineffective because clients could not always make their requests in English or indicate the language needed.

Other studies have likewise reported diet-related chronic conditions; dental concerns; transportation, financial and insurance barriers; poor navigation skills (e.g., making appointments, filling prescriptions, paperwork); language, literacy and cultural barriers; and mental health disorders.[32–34] The combination of barriers to health services and quality care, poor diet and limited navigation skills likely increases risk of poor health outcomes for resettled refugees. However, these communities have strengths, both cultural and in terms of social cohesion, on which future research and interventions may focus.

The study has limitations. Service provider perceptions are by definition subjective and open to bias, but many of the patterns reported here have been observed in other studies. This study sought to evaluate patterns associated with health and quality of life for a diverse local refugee community, so its results may not be applicable to some refugee groups. Lastly, Guilford County’s large immigrant and refugee population has led to greater availability of refugee- and immigrant-specific service organizations (e.g., Center for New North Carolinians, New Arrivals Institute) and marketplaces (e.g., grocery stores, clothing stores), in addition to cultural and religious support, resources that resettlement communities elsewhere in the USA may not have.

CONCLUSION

Service providers’ perceptions of environmental, nutritional and health issues and barriers for resettled refugees in Guilford County need to be corroborated by other methods, including direct observation and surveys of refugees themselves. Potential environmental risks and barriers (e.g., housing safety, lack of green space) and their effects on health (e.g., physical inactivity, chronic disease, mental health issues) should be further investigated, particularly in light of the limited power and language barriers faced by refugee groups. Despite reported concerns, many strengths (e.g., preference for fresh foods, skills and interest in growing food, sense of community/family) were also described and may offer promise of improvements in reducing food insecurity, poor dietary habits, physical inactivity and mental health problems.

Moreover, the potential mental health benefits of working outdoors and growing fresh, traditional foods and replication of many groups’ previous agrarian lifestyles should be further investigated. Development of targeted resources or training for resettled refugees could improve navigation of health services and the local food environment.

The strong sense of community reported within resettled communities suggests potential for training lay health educators to assist in meeting resettled refugees’ nutrition and health needs.