INTRODUCTION

Alcohol is one of the psychoactive substances most commonly consumed by adolescents and young adults[1] and its use is a major public health problem. Harmful use of alcohol—which includes irresponsible and inappropriate use, use against medical advice, and drinking to the point of intoxication—presents a serious threat to health, well-being and life.[2] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), harmful use of alcohol is a causal factor in more than 200 diseases and leads to 3.3 million deaths worldwide (5.9% of all deaths) annually.[3]

Alcohol is a central depressant and can cause psychological and physical dependency.[4] The biological, psychological and social effects of early-onset alcohol use can be dramatic and irreversible,[5] and the developing adolescent brain is particularly vulnerable to the addictive effects of alcohol and other drugs.[6,7]

Modern society has seen a rise in recreational drinking, affecting individuals from a wide range of ethnic, cultural, and sociodemographic groups. In addition, drinking is associated with many aspects of social and cultural life, and is taken for granted as a part of festive celebrations and social gatherings.[8] Even at levels not normally considered excessive, alcohol can cause serious harm,[9] but its deep cultural roots hinder implementation of public policies to curb its consumption.

Although public policies can sometimes encourage drinking (e.g., unrestricted retail access), they can also be a resource to prevent alcohol abuse and addiction. The most effective are those related to financial policy and pricing, regulation of availability and accessibility, and policies on drinking and driving.[10] Other effective tools for controlling alcohol-related problems are education programs for minors, modifications to drinking settings (for example responsible beverage service training), and (properly designed and implemented) public information campaigns.[11] For example, in the first decade of the 21st century, public health policies in Spain led to a decline in frequent consumption of wine and liquor among adolescents (although incidence of episodic intoxication rose).[12]

In Cuba, 45.2% of the population aged >15 years consumes alcohol, with a 7%–10% alcoholism prevalence (one of the lowest in Latin America).[13] On average Cubans begin to drink at about age 15.[14] In 2014, approximately 23% of adolescent boys and 11% of adolescent girls started to drink before age 15 years.[15]

The Ministry of Public Health’s (MINSAP) prevention and treatment programs in community mental health services, psychiatric hospitals and primary health care cannot by themselves fully address the problem of alcohol harm in Cuba.[16] We also need concerted intersectoral actions. Intersectorality in health is defined as the coordinated intervention of institutions from more than one social sector through actions focused totally or partially on treatment of problems related to health, well-being and quality of life.[17]

Education is one key sector in this area. The Ministry of Education (MINED)’s Health Promotion and Education Program makes antismoking, antidrinking and antidrug education part of core curriculum.[18] According to the program, by the end of ninth grade, students should have learned about the negative effects of excessive alcohol use, and by the end of twelfth grade, they should express negative attitudes to alcohol, in light of its harmful effects.

Cuba has a long tradition of alcohol production, and alcohol producers and manufacturers constitute another important sector in prevention of alcohol-related harm. This group has taken an interest in preventing underage drinking, based on a policy of corporate social responsibility,[19] defined as a company’s ongoing commitment to adhering to ethical guidelines and contributing to economic development while improving the quality of life of its employees, their families, local communities and society at large.[20] Historically, discussions of corporate social responsibility have centered on corporate ethics and the degree to which companies support society with contributions of money, time, and talent (including support for sustainable development and collaboration with governments, the public health sector, and scientific and academic communities).[21,22] Companies in the beer–wine–liquor sector have promoted a new global platform on responsible drinking based on explicit commitments, especially to reducing alcohol use by minors and drivers.[23] Cuba’s leading alcohol producer, Havana Club International S.A. (HCI), has had a corporate social responsibility policy aimed at reducing alcohol harmful use since 2013.[24]

This paper describes an intersectoral intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in a group of Cuban adolescents, a collaboration among the Medical University of Havana’s Academic Development Center on Drug Dependency (CEDRO; representing the academic sector), MINED (representing the education sector), and HCI (representing the business sector).

INTERVENTION

Objective, justification and population The objective was to promote adolescents’ awareness of alcohol-related risk, negative attitudes to alcohol, and alcohol-free lifestyles and behaviors. The intent was to respond to adolescents’ need to empower themselves to choose healthy behaviors with respect to drinking, in accordance with MINSAP’s National Comprehensive Adolescent Health Program 2012–2017[16] and MINED’s Health Promotion and Education Program.[18] Activities were based on identifying the learning needs of ninth-grade students, through a pilot study of 23 adolescents who began their technical training in Havana’s Manuel Fajardo Medical Faculty in the 2012–2013 academic year (in Cuba, middle-level health technicians receive their training at medical schools, where they have separate facilities and teachers). Included were students considered vulnerable to developing habitual use of alcohol or other drugs, by virtue of coming from dysfunctional homes, having poor academic records and being unmotivated by the specialty they were studying. Participants proposed that the intervention be called “You Decide,” since they saw it as providing them with the skills to make correct decisions about drinking.

Following the pilot study, we recruited 312 10th-grade students (189 girls and 123 boys aged 14–15 years) in 14 educational institutions (high schools or vocational technical schools) in Havana during the 2014–2015 academic year (4 high schools and 10 medical faculties).

Activities The intervention, conducted from September 2014 through July 2015, involved various activities: 1) lectures on early onset of alcohol use and its consequences, in order to increase perception of risk; 2) cultural and sports activities to enrich lifestyles and develop personal resources and recreational activities not involving alcohol consumption; and 3) activities to encourage development of life plans.

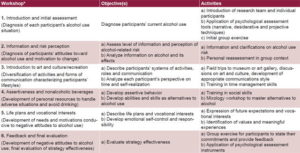

CEDRO was responsible for coordinating the project and implementing activities to demonstrate alcohol’s harmful health effects. MINED facilitated access to students, programmed biweekly project activities during regularly scheduled classes, and supported vocational and sports activities. HCI collaborated with cultural activities and organized workshops on nonalcoholic drinks, financed the printing of evaluation instruments and educational materials, and contributed resources for student transportation, an awards contest, and a concert for the program finale. Educational activities included workshops using participatory techniques and group exercises. The workshops, objectives and activities are presented in Table 1.

Indicators, data collection and analysis The main indicators were attitudes, motivation, interests and perception of risk; also examined were peer relations, academic performance, development of personal resources, and sense of health and well-being. Qualitative procedures (specifically narrative, desiderative and projective techniques) were used.[25] The narrative element consisted of an essay on the topic of alcoholic beverages, to elicit attitudes (positive, negative or neutral). The desiderative technique involved having each student list and rank their ten main goals and aspirations, to identify information concerning “Healthy cultural and recreational interests” and “vocational interests and future plans.” The projective technique called for students to complete phrases concerning key indicators (coping resources, social relationships, family conflicts, health problems, perception of risks and motivation to modify risky behaviors). Before and after the intervention, participants received printed questionnaires or instructions and responded in writing. Teachers provided information on academic performance. All information was entered into a database and the results were presented in percentages. Content analysis was done of the material gathered through the various techniques.

Table 1: Intersectoral strategy for prevention of early alcohol use in Cuban adolescents

*While all three sectors involved in the intervention participated in every workshop, each sector was in charge of two of the six:

Academic sector—Workshops 1 and 2

Business sector—Workshops 3 and 4

Education sector—Workshops 5 and 6

Ethics The study was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the General Calixto García Medical School, and authorized by MINED and the directors of participating institutions. Participants were assured of confidentiality; they and their parents provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

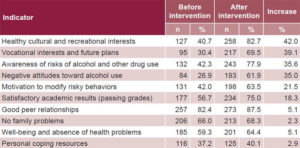

Prior to the intervention, 62.2% (194/312) of participants had initiated occasional drinking. No additional students initiated drinking during the intervention, and after it, there was a rise in indicators suggesting a shift toward healthy cultural and recreational activities (from 40.7% to 82.7%) and formulation of vocational aspirations in life plans (from 30.4% to 69.5%). Perception of the risks involved in drinking and drug use increased appreciably (from 42.3% to 77.9%). There was a concomitant increase in negative attitudes toward drinking (from 26.9% to 61.9%) (Table 2).

At the cognitive level, participants were better informed about risks associated with early-onset alcohol use, allowing them to understand the effects of alcohol on the human body and develop their perception of alcohol-related risks. At the behavioral level, interests were promoted that encouraged behaviors not associated with alcohol use, such as visits to cultural centers for exhibits and performances, and community activities related to vocational interests. We observed that students developed motivation and experiences that empowered them to reject alcohol use during adolescence.

Participants’ willingness to enrich their lifestyles also increased through development of various cultural, sports and recreational activities. Motivation to modify risky behaviors (such as limited participation in social activities and little time devoted to individual study and personal development) increased from 42% to 63.5% (Table 2), suggesting that reinforcing negative attitudes towards drinking can help students steer clear of unhealthy behaviors. The proportion of students with satisfactory academic results (passing grades) also improved (from 56.7% to 75%) (Table 2). While other educational activities besides the intervention may have come into play, it is plausible that the development of vocational interests and future projects also helped nurture academic performance.

Table 2: Results of intersectoral strategy to prevent early onset of alcohol use by Cuban adolescents (n = 312)

There were only modest increases in the remainder of the indicators. For example, good peer relationships were already common before the intervention, and this type of intervention could not be expected to modify domestic conflicts or students’ preexisting health problems. Substantial changes in personal resources were also unlikely, since adolescent brains have not yet fully developed the capacity to effectively manage complex environmental contingencies.

The 312 direct beneficiaries launched social communications activities in their schools and invited their peers to activities that reinforced negative attitudes toward drinking, such as a contest in which students expressed their views on the issue through drawings, photography and stories. The grand finale of these activities was a concert, with a band chosen by the students. The levels of participation in the contest and concert revealed the relative impact of the intervention in the 14 schools in which it was applied.

Study participants thus became health promoters for addressing the problem of harmful alcohol use and had a positive impact on their classmates: Close to 1500 of these were indirect beneficiaries of the intervention.

In each school, permanent groups were formed to work on prevention of alcohol and drug use, in which intervention participants presented their experience. These groups were a resource that helped influence straggling participants whose results were less satisfactory. In addition, psychological counselling was provided to individual adolescents with family and social problems that negatively affected either their results during the intervention or their academic performance.

Although most participants had already begun drinking occasionally at the beginning of the intervention, indicators of negative attitudes toward drinking increased after the intervention, with the strengthening of new interests and projects.

LESSONS LEARNED

The intervention stimulated adolescents’ interest in participating in organized activities and learning more about the issue, and raised their awareness to the point of changing their behavior, with concomitant improvement in most indicators examined. Providing essential information on the risks of harmful use of alcohol and other substances during adolescence helped generate decision-making autonomy among both direct and indirect beneficiaries.

Direct participation by two other sectors in the interventions’ conception and implementation highlights intersectorality’s potential as a resource to address complex health situations. In light of these positive results, MINSAP’s School Health Division and MINED approved extension of the intervention to several Cuban provinces—with a view to eventual coverage throughout the country—as part of a strategy to improve the health and well-being of children and adolescents.