ABSTRACT

Health is a universal human right, which should be safeguarded by government responsibility and included in all social policies. Only as such it is possible to ensure effective responses to the health needs of an entire population. The Cuban Constitution recognizes the right to health, and the country’s single, free, universal public health system and high-level political commitment promote intersectorality as a strategy to address health problems. Intersectorality is reflected in national regulations that encourage participation by all social sectors in health promotion/disease prevention/treatment/rehabilitation policies and programs. The strategy has increased the response capacity of Cuba’s health system to face challenges in the national and international socioeconomic context and has helped improve the country’s main health indicators. New challenges (sociocultural, economic and environmental), due to their effects on the population’s health, well-being and quality of life, now require improved intersectoral coordination in the primary health care framework to sustain achievements made thus far.

KEYWORDS Universal coverage, public health, health policy, social planning, intersectoral collaboration, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

Universal health coverage and universal access to health care require participatory policies including all sectors of society that in one way or another are associated with social, economic and environmental conditions—key aspects for sustainable human development.[1]

Public and social policies should be at the center of national responsibility for the State and the various sectors of public administration, to ensure human health and safety and exercise of civil rights, as well as to generate capacities and avenues for active, creative, committed popular participation, the basis of sustainable development.[2]

In 2000, the UN established the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), with specific targets to be met by 2015. At the global level many of these targets were not met, or progress was irregular, with wide differences among countries and population groups within countries.[3,4] These have been superceded by the 17 social, economic and environmental goals known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs have 169 associated targets, to be met through partnerships and concerted actions that prioritize the most vulnerable groups. The agenda also proposes guidelines to reach these targets.[5] The third SDG (“Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”) is subject to the success of the rest, indicating the integral and indivisible nature of these goals.[6]

IMPORTANCE This paper underscores health as an essential component in policies for all Cuban sectors and society in general. As other countries debate ways to overcome segmentation and fragmentation in their health systems, Cuba can point to the successes of a unified system that recognizes health as a universal right. The system now is challenged to increase efficiency while maintaining quality services, as well as to strengthen scientific research and continuing professional education.

The expanded conceptual framework called new public health or one health recognizes health as a social product, the result of the interrelationships among nature, society and social reproduction.[6] This perspective implies that all social sectors should be actors in the construction of health.[7] Furthermore, health plays a dual role as component and condition of development. Component, because it is essential to the concept of development, one of the basic dimensions of the human development index, represented by life expectancy at birth.[8] Condition, because poor health (at both individual and population levels) limits the possibilities for society’s sustainable development. Cuba’s recognition of health as a right and a priority—both conceptually and in development strategies, considered a broad social responsibility rather than a single sector’s exclusive mission—has contributed to the outcomes achieved despite the country’s scant resources. The purpose of this paper is to outline the results and challenges of public health in Cuba as an expression of health in social policies.

Cuba’s universal focus on public health Article 1 of the country’s Public Health Law (Law No. 41), in accordance with the 1976 Constitution, “establishes basic principles for regulation of social relations in the field of public health in order to contribute to ensuring health promotion, disease prevention, health recovery, patients’ social rehabilitation, and social welfare.”[9]

In the recently approved 2019 Constitution, Article 46 of Chapter II establishes that “all person have the right to life, physical and moral integrity, freedom, justice, security, peace, health, education, culture, recreation, sports and comprehensive development.” Article 72 states “public health is a right of all persons and it is the State’s responsibility to guarantee access to free, quality medical care, health protection and rehabilitation.[10] The State, to make this right effective, institutes a health system accessible to the population at all levels and develops preventive and educational programs, to which society and families contribute.”[11]

Cuban law recognizes health as a component and condition of development and as an instrument of social cohesion that includes all people and depends on the interrelation and conscious, active, committed participation by all actors and sectors of society. It also recognizes the need for organizational systems, as well as biomedical and public health technologies.

In this context, primary health care (PHC) becomes the crosscutting strategy for care at all levels. Professional and technical personnel are prepared for work in PHC through undergraduate and graduate educational programs across the country. Currently there are 81.9 physicians and 77.9 nurses per 10,000 population,[12–14] staffing some 10,000 neighborhood family doctor-and-nurse office, nearly 450 community polyclinics, 150 hospitals and various research institutes, as well as serving abroad. Newly graduated physicians do much of their training in PHC settings and are required to do a residency in family medicine before applying for any other specialty.

The health sector has evolved with the updating of Cuba’s economic and social model.[15] A process of transformation beginning in 2011 redefined the functions and structure of human resources needed and reclassified the various units of the health system’s three care levels, an important organizational initiative. Proposals to reorganize, regionalize and consolidate services (once institutions were reaccredited) were applied throughout the country. In the process, health indicators in Cuba have continued improving, relying on expansion of health care activities—from those based on health promotion and disease prevention, to curative and rehabilitative services. This transformation has involved the whole country and has reduced costs.[15]

These legal, strategic and operational frameworks sustain the universality of Cuban health care, which is not limited to providing easily accessible, quality services for all. The system also adheres to rational decision-making rooted in strategic planning, the concept of social determinants of health, and participation by broad societal sectors involving citizens at the community level.[15]

INTERSECTORALITY AS A STRATEGIC IN FORMULATING CUBAN PUBLIC HEALTH POLICY

Intersectorality is defined as coordinated intervention of representative institutions from various social sectors in actions partially or entirely aimed at addressing issues associated with health, well-being and quality of life.[11] It is a vital strategic component for formulating public health policy and the single consistent route to confronting health problems based on their causes and determinants, through integration and coordination of sectoral objectives and strategies.

Both conceptually as well as operationally, intersectorality rests on four pillars:

- Information, to construct a common language that facilitates understanding the aims and priorities of stakeholders in the health-building process;

- Cooperation, which can be strategic/systematic or ad hoc, manifested through implementation of policies, programs and interventions and not through their mere design or formulation;

- Coordination, which involves linking each sector’s policies and programs to seek greater effectiveness and efficiency, within a repertory of planned actions with concrete goals and defined responsibilities; and

- Integration, which represents a higher level from the policy- and program-formulating stages forward, reflected both in proposals and implementation strategies.

Intersectorality’s political foundation in Cuba—which includes health in the missions of all sectors and therefore as a component in all policies—is the recognition, first, of health as a right, and second, of public health and all its functions (promotion, prevention, curative care and rehabilitation) as organized efforts by the State and society as a whole. In this responsibility, the health sector plays a leading role in consolidating the four pillars described above.

For an intersectoral strategy to be successful, in addition to a clear conceptual definition and concrete goals, it must have a scientific approach based on sound health management practices and competent leadership with participation by leaders and managers in the intersectoral actions required to address each problem.[16]

Although intersectorality is a universal component in Cuba’s national health system, the natural setting to materialize it is the community and its local spaces, attuned to their particular contexts; geographic, sociodemographic and cultural characteristics; health needs and coordinated participation of related sectors and the community itself.[16]

The intersectoral approach has increased the national health system’s capacity in key areas, including childhood immunization; improved nutrition for pregnant women, children, and older adults; injury prevention; production and use of natural and traditional medicines; and addressing emerging and reemerging diseases. It has supported development of improved adolescent sexual and reproductive health, and contributed to healthier population aging. It has helped reduce the impact of environmental/climate-related disasters[17] and enabled access to improved water sources, as well as to sanitation in urban and rural areas.[13–15] All these advances have been possible through the coordinated actions of multiple sectors: education, agriculture, road infrastructure, waterworks, communications, culture, sports and recreation, science, technology, environment, housing, transportation, political organizations, civil society organizations, citizens in general and the health sector.

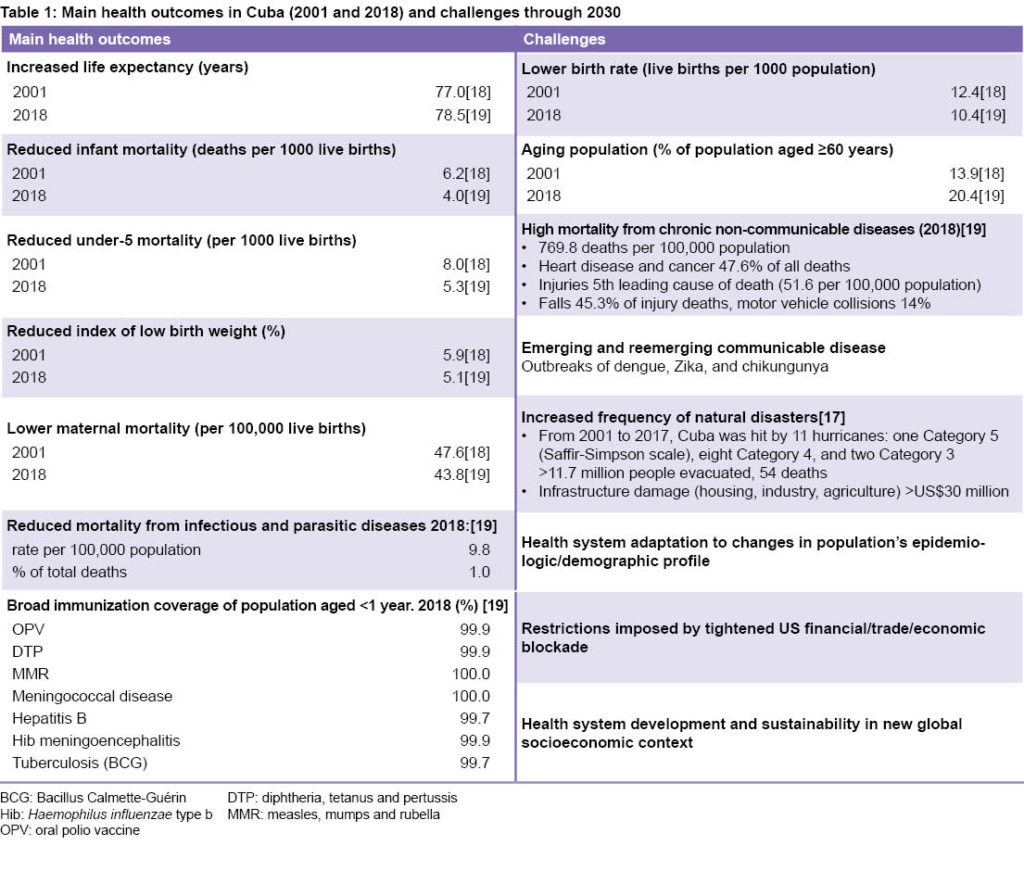

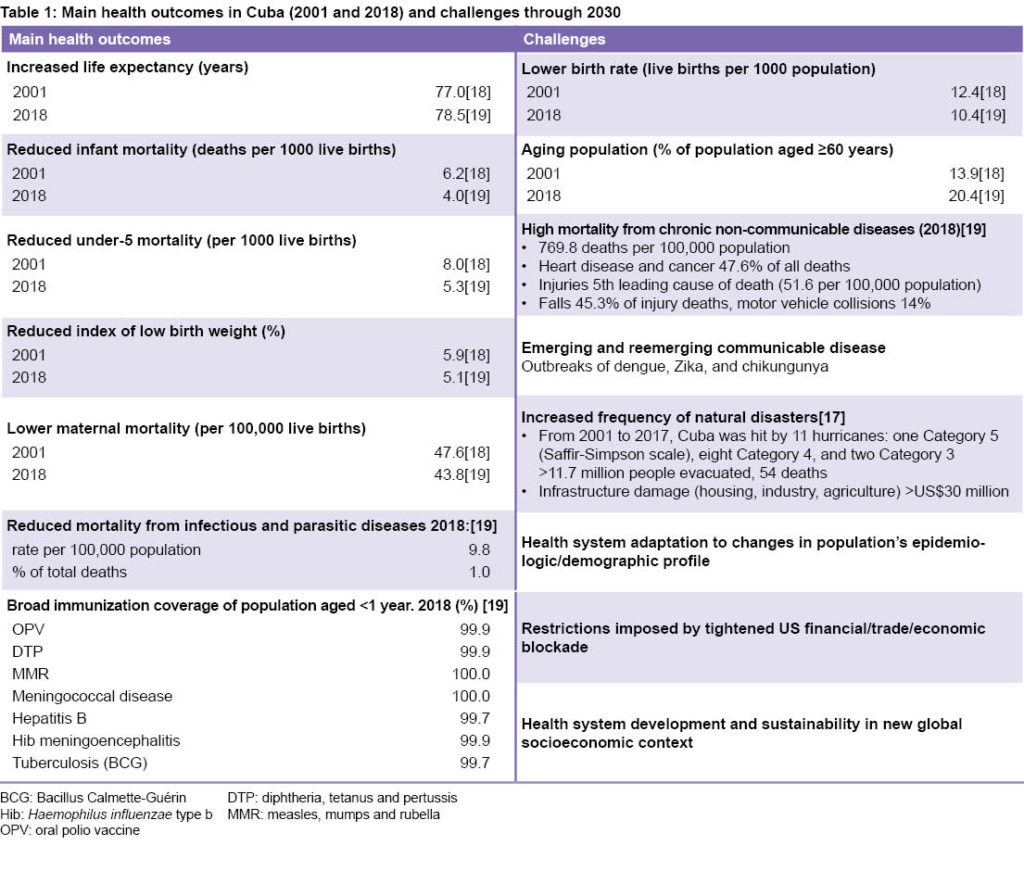

Table 1 presents recent achievements in Cuban health as well as the main challenges, several of which are common to the Americas Region and the world, while others have their own nuances due to Cuba’s particular geographic, economic and sociodemographic conditions.

UNIVERSAL HEALTH IN CUBA: CHALLENGES THROUGH 2030

In the Americas Region and globally, strategies are debated concerning how to place universal health at the center of all policies, not simply as a goal but as a continual process of construction. In Cuba, with its single, public health system offering full coverage and access, the problem consists of ensuring system sustainability, including continual improvements in efficiency, while maintaining quality of care.

During the Cuban health system’s transformation (which began in 2011 as the health sector’s response to the updating of the country’s economic and social model), several difficulties were identified and a set of actions proposed to resolve them.[15] Along with factors related to managerial competence and the system’s structure, organization and efficiency, inherent problems were identified in the geodemographic context, such as low fertility and birth rates, rapid population aging and effects of climate change.

Especially regarding these last factors, it is clear that the only way to address them is through concerted actions with other sectors and institutions. After a period characterized by increased efficiency from more rational administration/use of resources, without affecting quality, Cuba faces a special situation with the current US administration’s hostile actions, including a campaign to discredit Cuba’s health professionals and measures affecting important revenue sources associated with medical services provided overseas.[20]

Transforming the health system is a work in progress. Ongoing tasks include: reduction of costs, improved use of technology, training and ongoing renewal of human capital, as well as the system’s capacity to gather and analyze relevant, reliable information and to conduct monitoring and evaluation. Other actions include reengineering the system to align with the new life course perspective,[21] which has shifted understanding of the causal paths of health–disease processes, the skill set of traditional medical specialties, and the role of health services (particularly in older adult care), along with recognition of the growing importance of self care and the complementarity of individual and social responsibility for health.

Finally, it is critically important to strengthen and adapt education and training processes to generate sustainable skills in all sectors of Cuban society, in order to empower local leaders and managers, conduct scientific research projects responsive to local needs, and disseminate lessons learned.

References

- Pan American Health Organization; World Health Organization. 66a Sesión Del Comité Regional de la OMS para las Américas. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2014. Spanish.

- Jahan S. Informe sobre Desarrollo Humano. Washington, D.C.: United Nations Development Program; 2015.

- Ghosh J. Beyond the Millenium Development Goals: a Southern perspective on a global new deal. J Int Dev. 2015 Apr 5;27(3):320–9.

- United Nations. Una vida digna para todos: acelerar el logro de los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio y promover la agenda de las Naciones Unidas para el desarrollo después de 2015. A/68/202. Informe del Secretario General [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2013 Jul 26 [cited 2015 Sep 28]. 24 p. Available from: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/68/202&Lang=S. Spanish.United Nations [Internet]. New York: United Nations; c2019. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible.

- United Nations [Internet]. New York: United Nations; c2019. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. ONU aboga por ampliar el uso de energías limpias; 2015 May 22 [cited 2015 Sep 28]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/2015/09/la-asamblea-general-adopta-la-agenda-2030-para-el-desarrollo-sostenible/ONU. Spanish.

- El camino hacia la dignidad para 2030: acabar con la pobreza y transformar vidas protegiendo el planeta. Informe de síntesis del Secretario General sobre la agenda de desarrollo sostenible después de 2015. A/69/700 [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2014 Dec 4 [cited 2015 Sep 28]. Available from: http://www.un.org/es/comun/docs/?symbol=A/69/700. Spanish.

- Breilh J. La determinación social de la salud como herramienta de transformación hacia una nueva salud pública (salud colectiva). Rev Fac Nac Salud Pública [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Apr];31(Suppl 1). Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rfnsp/v31s1/v31s1a02.pdf. Spanish.

- United Nations Development Program. Indices e indicadores de desarrollo humano. Actualización Estadística de 2018 [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 10]. 112 p. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2018_human_development_statistical_update_es.pdf. Spanish.

- Ministry of Public Health (CU). Ley No 41 de Salud Pública, 1983 [Internet]. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 1983 Jun 13 [cited 2019 Apr 28]. 16 p. Available from: http://legislacion.sld.cu/index.php?P=FullRecord&ID=2. Spanish.

- Constitución de la República de Cuba. 2019 [Internet]. Havana: Government of the Republic of Cuba; 2019 Jan [cited 2019 Apr 10].16 p. Available from: http://media.cubadebate.cu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Constitucion-Cuba-2019.pdf. Spanish.

- Castell-Florit Serrate P. Comprensión conceptual y factores que intervienen en el desarrollo de la intersectorialidad. Rev Cubana Salud Pública [Internet]. 2007 Apr–Jun [cited 2019 Apr];3(2). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34662007000200009. Spanish.

- López Puig P, Segredo Pérez AM, García Milian AJ. Estrategia de renovación de la atención primaria de salud en Cuba. Rev Cubana Salud Pública [Internet]. 2014 Jan–Mar [cited 2018 Oct 1];40(1):75–84. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34662014000100009&lng=es. Spanish.

- Herrera Alcázar VR, Presno Labrador MC, Torres Esperón JM, Fernández Díaz IE, Martínez Delgado DA, Machado Lubián MC. Consideraciones generales sobre la evolución de la medicina familiar y la atención primaria de salud en Cuba y otros países. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr [Internet]. 2014 Jul–Sep [cited 2017 Oct 1];30(3):364–74. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-21252014000300010&lng=es. Spanish.

- Rojas Ochoa F. El camino cubano hacia la cobertura universal 1960-2010. Rev Cubana Salud Pública [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Oct 1];41(Suppl 1). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34662015000500003&lng=es. Spanish.

- Morales Ojeda R, Mas Bermejo P, Castell-Florit Serrate P, Arocha Mariño C, Valdivia Onega NC, Druyet Castillo D, et al. Transformaciones en el sistema de salud en Cuba y estrategias actuales para su consolidación y sostenibilidad. Rev Panam Salud Pública [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 10];42:e25. Available from: https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2018.25. Spanish.

- Gispert Abreu E de los A, Castell-Florit Serrate P, Lozano Lefrán A. Coverage and its conceptual interpretation [reprint]. MEDICC Rev [Internet]. 2016 Jul [cited 2019 Aug 15];18(3):41–2. Available from: http://mediccreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/mr_555.pdf

- Mesa Ridel G, González García J, Reyes Fernández MC, Cintra Cala D, Ferreiro Rodríguez Y, Betancourt Lavastida JE. El sector de la salud frente a los desastres y el cambio climático en Cuba. Rev Panam Salud Pública [Internet]. 2018 Apr [cited 2019 Feb 17];42:e24. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2018.24. Spanish.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU). Anuario Estadístico de Salud, 2001 [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2019 Feb 17]. Available from: http://bvs.sld.cu/cgi-bin/wxis/anuario/?IsisScript=anuario/iah.xis&tag5003=anuario&tag5021=e&tag6000=B&tag5013=GUEST&tag5022=2001. Spanish.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU). Anuario Estadístico de Salud, 2018 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 17]. 204 p. Available from: http://files.sld.cu/bvscuba/files/2019/04/Anuario-Electr%C3%B3nico-Espa%C3%B1ol-2018-ed-2019-compressed.pdf. Spanish.

- Anderson JL. Mexico, Cuba, and Trump’s Increasing Preference for Punishment Over Diplomacy. The New York Times [Internet]. 2019 Jun 11 [cited 2019 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/mexico-cuba-and-trumps-increasing-preference-for-punishment-over-diplomacy

- Bacallao Gallestey J, Alerm González A, Ferrer Arrocha M. Paradigma del curso de la vida. Sus implicaciones en la clínica, la epidemiología y la salud pública. Havana: ECIMED; 2016. 60 p. Spanish.

THE AUTHOR

Pastor Castell-Florit Serrate (serrate@infomed.sld.cu), physician specializing in public health administration, with a doctorate in health sciences and advanced doctorate in science. Director of Cuba’s National School of Public Health, Havana, Cuba.

Submitted: May 10, 2019 Approved: September 05, 2019 Disclosures: None