ABSTRACT

The first 1000 days of life constitute a short and exceptionally important period when the foundation is established for children’s growth, development and lifelong health. Cuba has a comprehensive care system for this population that aims to promote the best start in life so that children can reach their highest development potential. This is carried out through the national public health and education systems and also includes elements of health protection, prevention of harm and disease and social welfare for children.

Cuba’s infant mortality rate has remained <5 deaths per 1000 live births for 10 consecutive years, and in 2017 reached 4 per 1000, the lowest rate to date. The mortality rate for children aged <5 years in 2017 was 5.5 per 1000 live births, with a survival rate of 99.5%; low birth weight was 5.1% and vaccination coverage >95%. Among children aged 1 year in Cuba’s Educate Your Child program in 2014, >90% met age-specific indicators in all four developmental domains (intellectual, motor, socioaffective and language). Cuba has universal coverage for antenatal care and, in 2017, 99.9% of births occurred in health institutions. All working mothers receive paid antenatal leave from 34 weeks of gestation, continued through the child’s first year, to facilitate breastfeeding and child care. In 2018, the Cuban government allocated 27% of its national budget to health and social welfare and 21% to education.

KEYWORDS Growth and development, child development, child health services, preventive health services, primary health care, pregnant women, children, child rearing, intersectoral collaboration, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

The first 1000 days of life, from conception through two years old, constitute a short and exceptionally important period in which the foundation is laid for children’s growth, development and lifelong health. Recent evidence confirms, as described in The Lancet 2016 series on early childhood development, that harmful exposures cause the greatest damage and interventions have the most beneficial effects during this time.[1–3]

There is consensus on what children need for growth and development during these first 1000 days. A Washington DC-based nonprofit, 1000 Days, was created in 2010 to promote actions during this period, and formulated a set of evidence-based proposals for interventions to provide the best start in life for optimal growth and development.[4] In 2013, WHO published Essential Nutrition Actions, a guide that summarizes recommendations for improving nutrition for mothers and children in the first 1000 days of life.[5] Another series in The Lancet argues for implementation of national programs for this stage of life that reflect a multisector approach, including such vital aspects as health, nutrition, safety and protection, responsive caregiving and early learning.[3,6] Policies that prioritize such child development programs (and financial support for them) are essential to success.[7]

IMPORTANCE This article reports on Cuba’s comprehensive programs for children during their first 1000 days of life, a period with exceptional opportunities to establish the foundation for optimal health and development. It also reviews Cuba’s performance regarding the 1000 Days recommendations.

This article documents the main characteristics of Cuba’s approach to caring for children in the various stages of the first 1000 days of life. It discusses several main achievements and the role Cuba’s 1000 Days proposals play in helping every child reach their full potential. It also refers to several challenges in the current global and domestic context.

CUBA’S 1000 DAYS APPROACH

Cuba’s objectives and goals for care in the first 1000 days of life are aligned with WHO’s Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030)[8] and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals 2030.[9] These aim to ensure healthy pregnancy and birth for all mothers and optimal growth and development for all children and adolescents.

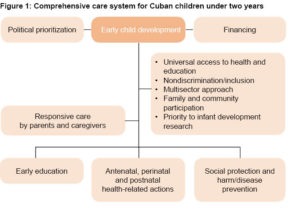

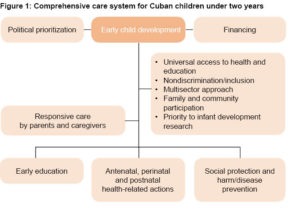

In line with these global platforms, the Cuban government has developed a comprehensive care system to promote the best start to life for the infant population and each child’s development (Figure 1). It is implemented across Cuba through the public health and education systems, and is based on health promotion and disease prevention, plus early stimulation of child development. It promotes active family and community participation, and its universal reach incorporates principles of equity and intersectoral involvement, including social welfare programs.[10]

Health care for Cuban mothers and children While many sectors must play a role in meeting the needs of small children, health institutions provide a critical starting point, due to the impact of their services for pregnant women, small children and families. Cuba’s universal public health system assures delivery of such interventions through various national programs for the obstetric and pediatric populations.[3]

In particular, the National Health System promotes maternal and child health during the 3 stages of the first 1000 days of life: antenatal, perinatal and postnatal (corresponding to pregnancy, lactation and early infancy) through its National Maternal–Child Health Program. It rests on a primary health care foundation, with services assured through 10,869 family doctor-and-nurse offices distributed in neighborhoods nationwide, each affiliated with one of 450 polyclinics (multispecialty primary care clinics), providing universal coverage to Cuba’s 11,239,114 inhabitants, of whom 120,458 were aged <1 year and 498,723 were aged 1–4 years in 2016 data.[11–13]

Health actions at key stages in the first 1000 days of life Antenatal stage: from conception to birth Antenatal care is preceded by a program for prevention of reproductive risk prior to pregnancy. This program represents a priority strategy to help ensure that women begin their pregnancy at the most appropriate time for their health and that of their unborn child. It provides guidance to couples on prophylactic use of folic acid and helps detect preconception risk factors or diseases to offer possible interventions. As a result of these services and educational programs, 74% of Cuban women who are married or in a committed relationship use some type of contraception.[14]

Once pregnancy has begun, various actions help mothers and families adequately prepare—both physically and emotionally—for gestation, delivery and childrearing. The main ones at this stage include:

- add women to the pregnancy roster of their family doctor-and-nurse team early in gestation (before 12 weeks), to ensure care specific to their condition;

- in normal pregnancies, ensure ten family doctor appointments over the duration of pregnancy and four with an obstetrician;

- ensure up-to-date maternal vaccinations;

- ensure cervical cancer screening is up to date;

- when risk factors are found, recommend additional tests for women and their partner(s);

- screen for cervicovaginal infections, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cervical changes and arboviral infections;

- prepare prospective parents physically and psychologically for childbirth and offer guidance on responsive parenting;

- provide preconception and antenatal genetic counseling, and implement programs for detection of congenital abnormalities and genetic diseases that enable couples to make informed decisions regarding pregnancy continuation when fetal problems are discovered; and

- ensure delivery by qualified birth attendants in a health care facility (While antenatal care is provided by primary health care services at the community level, virtually all deliveries, including those in remote areas, take place in health care institutions, attended by qualified personnel, 99.9% in 2016).[12]

Three important aspects are addressed in followup during this period: nutrition for pregnant women, antenatal stimulation and antenatal well-child counselling.

Nutrition for pregnant women. Good nutrition from the first moments of life provides the resources needed for proper brain and immune system development and for healthy growth. Nutrition also plays an important part in pregnancy through its action at the epigenetic level, and its effects can be seen throughout life—for example, in a predisposition to obesity and certain chronic diseases. Moreover, such epigenetic changes can be passed on to succeeding generations.[4]

Pregnant Cuban women are given supplemental iron and folic acid and provided with a government-subsidized food basket from the 14th week of pregnancy. If needed, they can be admitted to maternity homes, which were created in the 1960s. These homes, an example of intersectoral practice, emerged to promote institutional delivery by pregnant women living in remote areas and to provide adequate nutrition. They later diversified their services to provide care for at-risk women at any stage of pregnancy and became an essential resource for antenatal care. Cuba’s 131 maternity homes currently accept women with at-risk pregnancies not requiring hospitalization, ensuring them on-site medical care, appropriate diet, education about parenting and a supportive environment.[12,15]

Antenatal stimulation. In antenatal visits, parents are taught the benefits of fetal motor, visual and auditory stimulation for cerebral and sensory development, and subsequent physical, psychological and social development. They are also taught how to provide such stimulation, which in addition helps foster a caring connection between parents and their unborn child. This is especially important in the second and third trimesters; thus at 20 weeks, parents learn to communicate with their unborn child, which also helps them prepare physically and emotionally to welcome the infant into the family.[16]

Antenatal well-child counselling. This is provided during pregnancy to help parents prepare to care for their child. Topics covered include the value of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months (supplemented with other foods after this age), and the importance of ongoing well-baby visits. Physiological events in the first days of life are explained to both parents and family members during house calls and antenatal doctor visits, and information provided on prevention of unintentional injuries (e.g., asphyxia from cosleeping or incorrect sleeping positions), as well as the infant’s need for stimulation and affection.[17]

Perinatal and postnatal stages: newborns and young children up to two years Comprehensive care in early childhood is carried out through well-child visits that provide multidisciplinary advice aimed at promoting optimal growth and development, preventing disease and reducing risks, identifying and managing health problems early, guiding parents to care for their children and teaching them to care for themselves.[17] Metabolic screening tests are performed in newborns for early detection of congenital hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, biotinidase deficiency and galactosemia. Other programs apply specific strategies to control childhood communicable diseases (e.g., immunization), implementing national action plans in primary and secondary care settings using guidelines for control of diarrheal and acute respiratory diseases, infectious neurological diseases and arboviral diseases.

Family doctors and nurses hold well-child visits in their offices (with support from polyclinic pediatricians, as needed), frequency depending on age and health status. In these visits, providers monitor health and physical and psychomotor development and offer counseling on nutrition, hygiene, immunization and early stimulation. Parents are advised how to manage emergencies. Followup house calls also allow health personnel to gain a better understanding and appreciation of family conditions and lifestyle.

Nutrition education is provided through guidelines for children aged <2 years, and growth is monitored in well-child visits to detect and help correct nutritional deficiencies and excess weight gain. Another program promotes exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months and continued breastfeeding until age two years. A network of human milk banks, based in provincial maternity hospitals, distributes quality human milk provided by voluntary donors to the most vulnerable children.[18] A subsidized food support program for children, similar to that for pregnant women, provides all Cuban children one liter of milk per day up to age seven years, among other foodstuffs.

The quality of well-child followup is continuously monitored in order to improve results in areas where there are important challenges for comprehensive care, such as breastfeeding duration and prevalence of anemia and overweight.

Early childhood education Cuban children receive early education services via two routes, institutional and extrainstitutional. The institutional one involves círculos infantiles (daycare centers for children of working mothers). Infants can attend daycare centers as soon as they are able to walk (around one year) and until they reach age six years. About 18% of Cuban children attend these círculos.

The extrainstitutional route is the Educate Your Child program, which reaches about 68% of parents. Program promoters in each community recruit and train voluteers to deliver early childhood education. The program is managed through collaborating groups at various political and administrative levels in Cuba, coordinated by the Ministry of Education. It also involves several other sectors and organizations, including health, justice, culture, sports, social assistance, radio and television, mass organizations, research centers and universities.

The program is based on family, community and intersectoral action, and promotes training families to improve their skills to carry out activities to stimulate child development at home. Community activities are organized to stimulate language and development of intellectual, motor and social skills. The program pays special attention to fathers’ active participation.UNICEF provides some guidance for the program and has recognized it as an example of good practices in child health.[11]

Social protection Cuban working women are entitled to paid parental leave. From 34 weeks’ gestation until 12 weeks after delivery, the benefit is 100% of the average weekly wage received over the 12 months prior to leave. After 12 weeks and until the end of the infant’s first year, mothers who choose not to go back to work receive 60% of their wage.[19] Parental leave may be shared with the father or a grandparent after the child reaches age six months (before which, exclusive breastfeeding is recommended).[10]

In coordination with the Ministry of Public Health, all births are officially registered with the Ministry of Justice before newborns and mothers are discharged. Cuba is a party to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child[20] and makes no distinction between children of married or unmarried parents.

A prevention system serves children with social, health, economic and family problems, and various programs (among them, Educate Your Child) provide attention to children with disabilities or without parental care. The Educate Your Child program’s coordinating groups in each locality help develop intersectoral intervention strategies for such cases, with family participation, and solutions are sought at different levels, from local to national.[8]

Research on child health and development There is consensus on global research priorities to promote early childhood development in order to reach the Sustainable Development Goals.[21] In Cuba, periodic studies of infant development conducted over more than four decades have provided information for formulating strategies to improve children’s wellbeing and quality of life. This research includes periodic population studies of growth and development of children and adolescents, and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys carried out with UNICEF.[14,22]

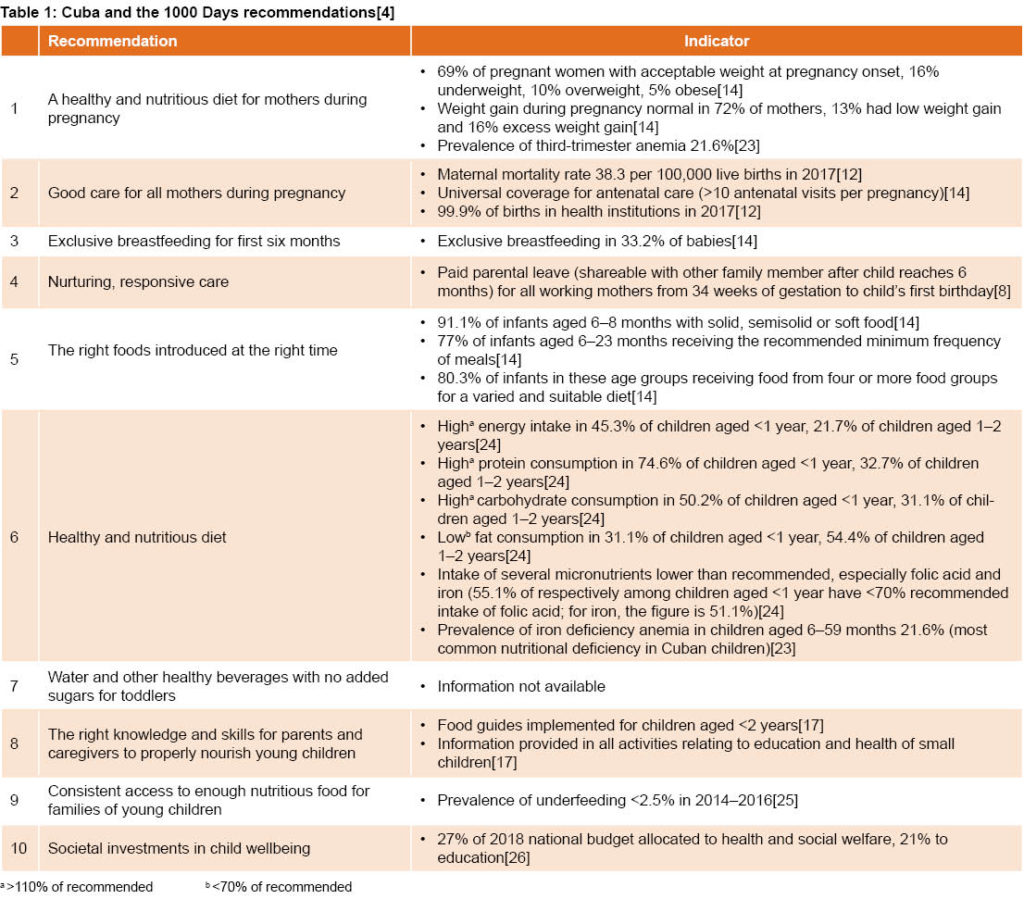

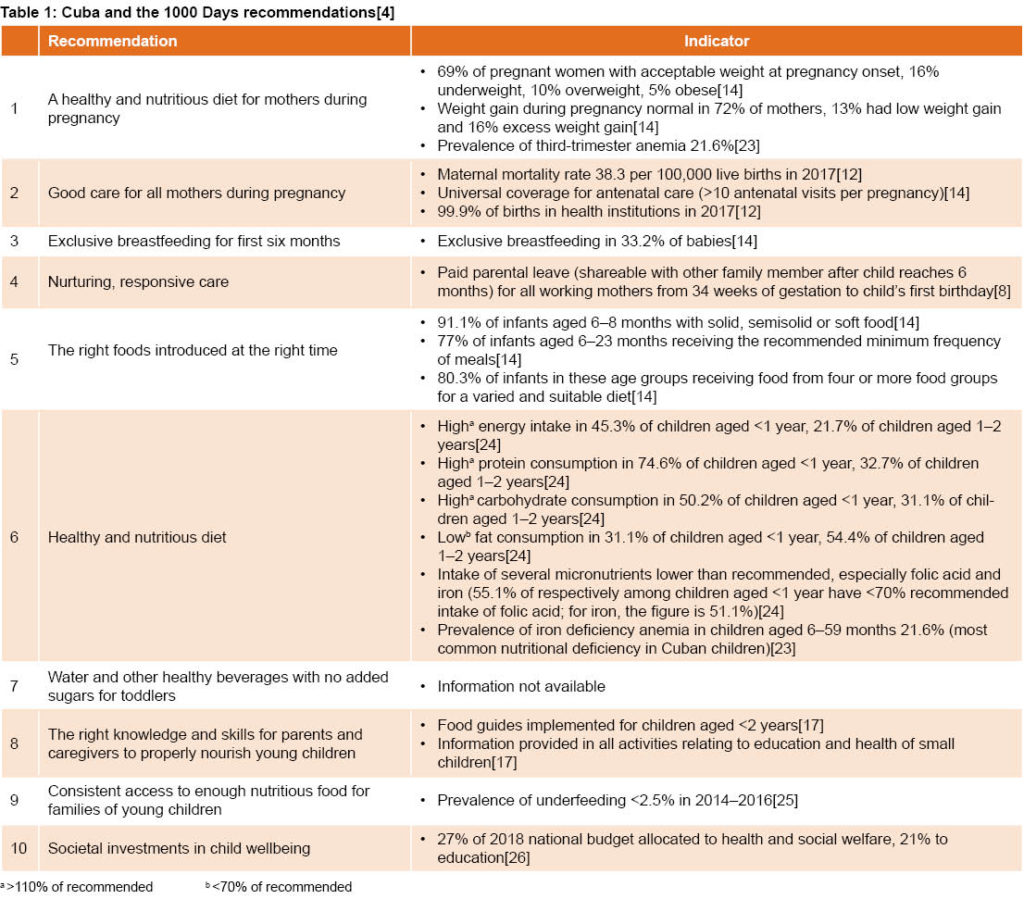

Table 1 shows key actions implemented in Cuba and indicators of progress on the 1000 Days proposals. Overall, Cuba’s performance is quite positive. Particularly noteworthy are results related to care of children and mothers, and the high proportion of Cuba’s national budget allocated to health and education. In 2017, there were over one million well-child visits for children aged <1 year, with an average of 14.6 per child.[12]

The actions described above, while they may not be deemed causal, have likely contributed to Cuba’s achievement of various important indicators (most recent years for which data are available):

- under 5 survival 99.5% in 2017;[12]

- infant mortality rate remaining under 5 deaths per 1000 live births for 10 consecutive years; 4 per 1000 in 2017, the lowest in Cuba’s history;[12]

- low birth weight prevalence 5.1% in 2017;[12]

- 7% growth retardation and 17% excess weight and obesity among children aged <5 years;[11,27]

- vaccination coverage >99% against polio, diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, mumps, measles, rubella, meningococcus, hepatitis B, H. influenzae b and tuberculosis;[12]

- access to improved drinking water sources for 94.2%, improved sanitation services for 90.7%;[14]

>90% of children aged 1 year in the Educate Your Child program (2014) meeting indicators in all developmental spheres (intellectual, physical, socioaffective and language);[8]

- Cuban women highly educated, with 99.7% literacy and average of 12.4 years of formal education,[28] 55.8% with at least high school or technical education, 14.5% university educated.[14]

Cuba still faces challenges in meeting food- and nutrition-related goals. It is particularly important to increase breastfeeding rates and reduce anemia prevalence in pregnant women and preschool children, as well as to stem the rising rates of overweight and obesity in recent years, associated with increasing incidence of non-communicable chronic diseases at early ages. It is also important to continue improving the quality of well-child visits, since they are ideal occasions for promoting health, monitoring child development, ensuring early stimulation and identifying children at risk for personalized interventions (Table 1).

CONCLUSIONS

In Cuba, care in the first 1000 days of life is provided through a comprehensive system that offers health actions, early education and social protection. While some challenges remain, the system has positively influenced indicators of infant and child survival as well as others concerning health, wellbeing, and optimal growth and development for all children. Such coordinated efforts are part of universal public health and education, also guided by intersectoral principles and participation.

References

- Cusick S, Georgieff MK. The first 1,000 days of life: The brain’s window of opportunity [Internet]. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti; 2017 [cited 2018 Feb 10]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/958-the-first-1000-days-of-life-the-brains-window-of-opportunity.html

- Lake A. The first 1,000 days: a singular window of opportunity [Internet]. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2017 Jan 18 [cited 2018 Feb 10]; [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://blogs.unicef.org/blog/first-1000-days-singular-opportunity/

- Richter LM, Daelmans B, Lombardi J, Heymann J, López F, Behrman JR, et al. Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet [Internet]. 2017 Jan 7 [cited 2018 Jan 10];389(10064):103–18. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31698-1

- 1000 days. The first 1000 days. Nourishing American´s future [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: 1000 Days; 2016 [cited 2017 Dec 20]. 64 p. Available from: https://thousanddays.org/wp-content/uploads/1000Days-NourishingAmericasFuture-Report-FINAL-WEBVERSION-SINGLES.pdf

- World Health Organization. Essential Nutrition Actions. Improving maternal, newborn, infant and young child health and nutrition, 2013 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013 [cited 2017 Oct 2]. 146 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/essential_nutrition_actions/en/Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, Andersen CT, DiGirolamo AM, Lu C, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet [Internet]. 2017 Jan 7 [cited 2018 Jan 10];389(10064):77–90. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7

- World Health Organization. Partnership for maternal, newborn and child health and WHO. A policy guide for implementing essential interventions for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health (RMNCH). A multisectoral policy compendium for RMNCH. [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 [cited 2017 Dec 12]. 51 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/policy_compendium.pdf

- org. Estrategia Mundial para la Mujer, el Niño y el Adolescente (2016–2030) [Internet]. New York: EveryWomanEveryChild.org; 2015 [cited 2018 Feb 6]. 6 p. Available from: http://www.everywomaneverychild.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/EWEC_GSUpdate_Brochure_ES_2017_web.pdf. Spanish.

- United Nations. Informe de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible 2016 [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 3]. 53 p. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/The%20Sustainable%20Development%20Goals%20Report%202016_Spanish.pdf. Spanish.

- Departamento Nacional de Salud Materno Infantil. Programa Nacional de Atención MaternoInfantil. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 1983. Spanish.

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Early childhood development in Cuba [Internet]. Havana: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2016 [cited 2018 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/cuba/cu_resources_earlychildhooddevelopmentlibro.pdf

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU). Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2017 [Internet]. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2018 [cited 2018 Feb]. 191 p. Available from: http://files.sld.cu/dne/files/2018/04/Anuario-Electronico-Espa%C3%B1ol-2017-ed-2018.pdf. Spanish.

- National Statistics Bureau (CU). Sistema de Información Estadística Nacional de Demografía [Internet]. Havana: National Statistics Bureau (CU); 2017 [cited 2018 Feb 13]. Available from: http://www.one.cu/. Spanish.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU). Encuesta de Indicadores Múltiples por Conglomerados. Cuba, 2014. Informe final [Internet]. Havana: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 7]. 263 p. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/cuba/mics5-2014-cuba.pdf. Spanish.

- Delgado G. Los hogares maternos: su fundación en Cuba y objetivos propuestos desde su creación. Cuad Hist Salud Pública [Internet]. 2004 Jan–Jun [cited 2018 Jan 6];(95). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0045-91782004000100016&lng=es.

- Hernández K. La estimulación prenatal: Evolución y beneficios. Anuario de Investigación [Internet]. 2016 Mar [cited 2018 Aug 20];65:361–76. Available from: http://www.diyps.catolica.edu.sv/wp-ontent/uploads/2016/08/25EstimulacionAnVol5.pdf. Spanish.

- Esquivel M, Álvarez G, Izquierdo ME, Martínez D, Tamayo V. Well child care: a comprehensive strategy for Cuban children and adolescents. MEDICC Rev [Internet]. 2014 Jan [cited 2018 Jan 7];16(1):7–11. Available from: http://mediccreview.org/well-child-care-a-comprehensive-strategy-for-cuban-children-and-adolescents/

- Gorry C. Cuba’s human breast milk banks. MEDICC Rev [Internet]. 2014 Jan [cited 2018 Jan 12];16(1). Available from: http://www.medicc.org/mediccreview/index.php?get=2014/1/12

- Consejo de Estado. Decreto Ley No. 339/2016 (GOC-2017-131-EX7). Gaceta Oficial República de Cuba Extraordinaria No. 7 [Internet]. Havana: Council of State of the Republic of Cuba; 2017 [cited 2018 Dec 20]. Available from: https://oig.cepal.org/sites/default/files/cuba_-_decreto_ley_339_y_340_de_2017_0.pdf. Spanish.

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. [Internet]. New York: United Nations [Internet]. 1989 [cited 2018 Dec 28]. Available from: https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-11&chapter=4&clang=_en

- Dua T, Tomlinson M, Tablante E, Britto P, Yousfzai A, Daelmans B, et al. Global research priorities to accelerate early child development in the sustainable development era. Lancet [Internet]. 2016 Dec [cited 2017 Dec 20];4(12):e887–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30218-2

- Esquivel Lauzurique M. Departamento de crecimiento y desarrollo humano: más de cuatro décadas monitoreando el crecimiento de los niños cubanos [Editorial]. Rev Habanera Cienc Médicas [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2018 Feb 20]:12(1)1–4. Available from: http://www.revhabanera.sld.cu/index.php/rhab/article/view/12/2. Spanish.

- Pita GM, Basabe B, Díaz ME, Gómez AM, Campos D, Arocha C, et al. Anemia and iron deficiency related to inflammation, helicobacter pylori infection and adiposity in reproductive-age Cuban women. MEDICC Rev [Internet]. 2017 Apr–Jul [cited 2018 Feb 22];19(2–3). Available from: http://mediccreview.org/anemia-and-iron-deficiency-related-to-inflammation-helicobacter-pylori-infection-and-adiposity-in-reproductive-age-cuban-women/

- Jiménez SM, Martín I, Rodríguez A, Silvera D, Núñez E, Alfonso K. Prácticas de alimentación en niños de 6 a 23 meses de edad. Rev Cubana de Pediatría [Internet]. 2018 Mar [cited 2018 Jul 30];90(1):79–93. Available from: http://www.revpediatria.sld.cu/index.php/ped/article/view/383/175.

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Plataforma de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional: Perfil Nacional de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional. Cuba [Internet]. Havana: FAO; c2015 [cited 2018 Nov 29]. Available from: https://plataformacelac.org/storage/app/uploads/public/5a9/fd9/d22/5a9fd9d22e966178346798.pdf. Spanish.

- Gaceta Oficial de Cuba. Ley 125 del Presupuesto del Estado para 2018. Gaceta Oficial No. 48, 2017 [Internet]. Havana: Government of the Republic of Cuba; 2017 [cited 2018 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.mfp.gob.cu/class/show_pdf.php?id=105&td=1. Spanish.

- United Nations Children Fund. El estado mundial de la infancia 2016. Una oportunidad para cada niño [Internet]. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2017 [cited 2017 Dec 3]. 171 p. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/spanish/publications/files/UNICEF_SOWC_2016_Spanish.pdf. Spanish.

- Rosales Vázquez S, Esquenazi Borrego A, Galeano Zaldívar L. La brecha de educación en Cuba con un enfoque de género. Rev Econom Desarrollo [Internet]. 2017 Jan–Jun [cited 2018 Nov 25];158(1):140–51. Available from: http://www.redalyc.org/html/4255/425553381011/. Spanish.

THE AUTHORS

Mercedes Esquivel-Lauzurique (Corresponding author: mesqui@infomed.sld.cu), pediatrician with a doctorate in medical sciences. Senior researcher, Julio Trigo López Medical Faculty, Medical University of Havana, Cuba.

Gisela Álvarez-Valdés, physician with dual specialties in family medicine and pediatrics and a master’s degree in comprehensive child health. Assistant professor, Julián Grimau Teaching Polyclinic, Havana, Cuba.

Bertha L. Castro-Pacheco, pediatrician with a master’s degree in comprehensive child health. Head, National Pediatrics Group and associate professor, Juan Manuel Márquez Pediatric Teaching Hospital, Havana, Cuba.

María C. Santana-Espinosa, pediatrician with a master’s degree in comprehensive child health. Associate professor, National School of Public Health (ENSAP), Havana, Cuba.

María del Carmen Machado-Lubián, pediatrician with a master’s degree in comprehensive child health. Associate researcher, National Hygiene, Epidemiology and Microbiology Institute Havana, Cuba.

Violeta Herrera-Alcázar, obstetrician with a master’s degree in comprehensive child health. Associate professor, ENSAP, Havana, Cuba.

Daisy Martínez-Delgado, physician with dual specialties in family medicine and pediatrics and a master’s degree in comprehensive child health. Assistant professor, ENSAP, Havana, Cuba.

Submitted: March 02, 2018 Approved: December 27, 2018 Disclosures: None