INTRODUCTION Globally, older adults are a population group that often suffers abuse by their caregivers. Along with women and children, they are among those most often reported as victims of abuse of any kind in Cuba.

OBJECTIVE Characterize presence of domestic abuse of older adults in family doctor-and-nurse office No. 28 of the Carlos Manuel Portuondo University Polyclinic in Havana, Cuba, determining the main manifestations of abuse and help-seeking behavior by the older adults identified as victims.

METHOD This was a descriptive cross-sectional study of adults aged ≥60 years; all those not diagnosed with dementia and who agreed to participate were interviewed. In a universe of 268 older adults, 29 were living outside the area, 24 declined to participate, and 18 had a diagnosis of dementia, leaving a study population of 197 individuals. Variables included: personal experience of abuse, type of abuse, perpetrator, help sought, and reasons for not seeking help. Statistical analysis was based on percentages.

RESULTS Of 197 older adults interviewed, 88 (44.7%) reported that they were victims of domestic abuse; 50 of these were women. The most common types of abuse were psychological abuse and disrespect for personal space, reported by 69 (78.4%) and 54 (61.4%) individuals, respectively. Sons- and daughters-in-law were identified as the abusers by 68 participants and grandchildren by 65. Of the 88 victims, 67 (76.1%) stated that they did not seek help.

CONCLUSIONS The finding that substantial numbers of older adults are victims of domestic abuse brings to light a hitherto insufficiently addressed issue in the community studied. More research is needed to deepen understanding of the scope and causes of the problem to inform prevention and management strategies, not only at the level of the polyclinic catchment area, but in the health system in general.

KEYWORDS Elder abuse, elder neglect, aged abuse, domestic violence, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

For decades, domestic violence was considered a private matter that did not affect many people. Now, however, many experts agree that it is widespread and its effects extend beyond the individual to his/her family and to society, and thus considered a population health problem.[1] All age groups of both sexes are affected by violence, but older adults, along with women and children, are a vulnerable group that frequently suffers abuse by caregivers or individuals close to them. Elderly people are particularly open to economic abuse by family members and others.[2,3]

Elder abuse can take many forms. The principal ones have been addressed by various disciplines (including psychology, psychiatry, criminology, sociology). Their perspectives may differ, but they share the same goal: understanding the factors and settings in which abuse/violence occurs and identifying its most common manifestations, in order to help address and mitigate them. Forms of abuse include the following, which are not mutually exclusive:[4]

- Psychological violence: includes verbal harassment, through insults, persistent criticism, discrediting, humiliation, silence, etc. A gesture, word or action can be destructive even if it does not leave visible signs, and it can have insidious consequences

- Sexual violence: imposition of a sexual act against the person’s will; this includes marital rape

- Physical violence: can occur together with any other type of violence

- Emotional violence: neglect of a person’s need for affection. Includes absence of bodily contact or caresses, indifference to emotional states, chronic verbal hostility (insults, taunting, disparagement or threats of abandonment)

- Economic violence: when the abuser controls financial resources and leaves the person’s basic needs unmet

- Violence through neglect and abandonment: lack of protection and physical care, lack of response to need for affection and cognitive stimulation, ignoring, failing to provide essential food and clothing

- Comprehensive violence: the systematic application of all these types by a single person

Elder abuse stems from multiple factors and constitutes a social as well as a health problem. Its victims are extremely difficult to identify unless the physical violence they suffer is sufficient to warrant medical treatment. In turn, aggressive or neglectful behaviors can be difficult to detect, and older adults may not recognize abuse or may be reluctant to report it.[5] In 2003, WHO reported a global prevalence of elder abuse of 4%–6%;[1] no more recent figures are available. Older age and greater dependency are associated with higher risk,[6] and the absolute numbers at risk are growing with population aging. UN data predict the proportion of the population aged >60 years to be almost 2 billion by 2050.[7]

In 2012, 18.3% of Cuba’s population of 11.2 million were aged ≥60 years.[8] Social programs have improved over the last few years, providing significant support to education, health, safety, social assistance, culture, etc., thus contributing to better quality of life for older adults and the population as a whole. Nevertheless, within this context, it is important to take a more profound look at lifestyles, living conditions, family attitudes and human/social relations as they pertain to aging and particularly elder abuse in the country.

Although Cuba’s health registries do not collect data on incidence and prevalence of abuse, several studies have reported on elder abuse in different sites across the country. A study conducted in two family doctor-and-nurse offices in Holguín Province in 2005–2007 found that between 63% and 100% of participating elders were victims of some sort of abuse.[9] In 2007–2008, Gómez studied elder abuse in the San Luis Municipality in Pinar del Río Province and found that 78.4% of the 90 individuals interviewed reported abuse.[10] In Griñán’s 2011 study of domestic elder abuse in a polyclinic catchment area in Santiago de Cuba, 67.7% of older adults reported abuse, as did an even higher proportion of those aged >85 years.[11]

These studies alert us to the presence of domestic elder abuse in several parts of Cuba. All health personnel—especially in primary care—have an obligation to identify and report elder abuse and to initiate actions to eliminate it. Hence this study was undertaken to identify and describe elder abuse in our community. The purpose was to characterize domestic elder abuse in the geographically determined catchment population of family doctor-and-nurse office No. 28 of the Carlos Manuel Portuondo Polyclinic’s health area in Havana, describing the main manifestations of abuse and service needs of elders identified as victims.

METHODS

Study design and population A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted of the universe of 268 adults aged ≥60 years enrolled in family doctor-and-nurse office No. 28 of the Carlos Manuel Portuondo University Polyclinic in Havana’s Marianao Municipality. Individuals residing outside the catchment area were excluded, as were those with medical conditions or psychiatric illnesses that could interfere with data collection reliability. The final study population included 197 persons (102 women and 95 men), 73.5% of the universe.

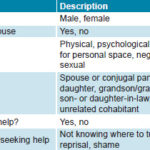

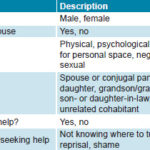

Variables The study applied the definition of elder abuse adopted by WHO in the Toronto Declaration: a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person.[12] Other variables are defined in Table 1.

Table 1: Variables

*per interview instrument endorsed by Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment for its intervention project Socio-pathological characterization of domestic violence in Havana[13]

Data collection and analysis Guide for Detection of Domestic Violence, an instrument endorsed by Cuba’s Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment for an earlier study, was used for data collection.[13] Prior to interviews, items were explained and participants’ questions or doubts were addressed. Data were entered in an Excel 2007 database and processed in JMP 5.1 (SAS Institute). Statistical analysis based on percentages was used and results were presented in tables constructed.

Ethics Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who agreed that study results could be published as long as their identities were not revealed. All older adults identified as victims of abuse received treatment and followup through a domestic violence clinic in Marianao Municipality’s Women and Family Counseling Center.

RESULTS

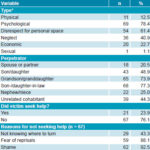

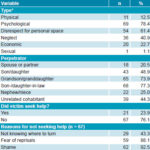

Of the 197 older adults surveyed, 88 (50 women, 38 men) reported some experience of abuse, for a prevalence of 44.7% (49% in women, 40% in men). The most common type of abuse was psychological, reported by 69 participants (78.4%) (Table 2). Specific types of psychological abuse reported, in order of frequency, were: threat of abandonment, humiliation, criticism in front of others, verbal harassment and getting blamed for family problems. Disrespect for personal space was reported by 54 participants (61.4%). Other types of abuse, reported by fewer than half the participants, included neglect and economic, physical or sexual abuse (Table 2).

Table 2: Type of abuse, perpetrator and help-seeking in persons aged ≥ 60 years (n = 88)

*per interview instrument endorsed by Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment for its intervention project Socio-pathological characterization of domestic violence in Havana[14]

Of the 88 participants who identified themselves as victims of elder abuse, only 21 (23.9%) reported having sought help on some occasion, generally from a relative. Of the 67 (76.1%) who did not seek help, 92.5% (62) said that they felt ashamed to reveal their situation, 88.1% (59) feared possible retaliation from their caregivers or that the situation could worsen, and 43.3% (29) reported that they did not know what organization or person could provide help (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

It is alarming that almost half the sample reported abuse. This finding corroborates previous findings about older adults’ vulnerability to abuse.[2,3,10–12,14,15] Nor are older adults exempt from gender violence; our observation that women reported abuse more frequently than men coincides with other study findings.[16–18] Societal myths reported in many societies may also operate in Cuba:[19]

- Domestic violence is a “family issue” that belongs in private life; no person or institution should intervene, because a family should not “air its dirty linen in public”

- Battered women are masochists and like to be abused

- Most aggressors are sick, poor and/or alcoholics

- Men are naturally aggressive and cannot control themselves

- The problem is inherent in prevailing traditions and customs; therefore, violence naturally arises in every family, but it is manageable

- The victim is to blame; the woman brings it on herself (the abuser commonly asks, Do you think I hit you for no reason?)

- Violence is part of masculinity. “Real men” hit women

Other researchers in Cuba and Mexico have corroborated our finding that abuse is most often psychological.[20–22] In a 2010 study in Manzanillo, Granma Province, Cuba, Enamorado observed that the most common type of elder abuse was psychological, especially in the form of insults.[20] Similar results were found by Márquez and Arvizu in a study of 680 older adults in Mexico.[21] In a study of psychological abuse among older adult patients seen at a polyclinic in Holguín Province, Cuba, Pérez found that 100% of participants had at some point been victims, the most common manifestations being rude responses to questions, use of profanity and offensive gestures. The most frequent psychological reactions on the part of older adult victims were chagrin and sorrow, and the most common behavioral responses were silence, acceptance and self-imposed isolation.[14] Griñán reported psychological violence in 89.6% of cases of elder abuse.[11] The type of psychological abuse we observed (threats of abandonment, humiliation, criticism in front of others, verbal harassment, and blaming for family problems) can have major emotional repercussions for the elderly victim and cause significant mental harm, since it can synergistically enhance whatever feelings of uselessness and vulnerability the victim may already be experiencing in the face of aging.[17]

Our findings concerning frequent disrespect for personal space and privacy of older adults are consistent with those of other Cuban studies. In Mendo’s 2011 study of 3382 older adult patients of the Frank País Polyclinic in Santiago de Cuba City, 27.2% reported that their personal space was not respected and 16.5% complained of isolation within the family.[22] Even if decreased housing stock and other aggravating factors in the current socioeconomic situation have contributed to a rise in crowded, multiple generation households, solutions must be found that do not discriminate against any particular family member, and families will need social support for this. Other Cuban authors warn that sustained disrespect for and violation of an older adult’s privacy can lead to a low-quality physical existence, since often the elder is unprotected and does not have the same ability to socialize with friends and others, potentially leading to unmet social needs, loneliness and isolation. Another consequence then is lack of easy access to information and the opportunities for education that exist.[23] In this regard, the UN states: Older persons should be able to enjoy human rights and fundamental freedoms […] with full respect for their dignity, beliefs, needs and privacy and for the right to make decisions about their care and the quality of their lives.[24]

Although fewer instances of other forms of abuse (financial, physical and sexual) were reported by participants, it is still of concern that these types of abuse occur in Cuba. In other Cuban studies, the percentages of older persons identified as victims of these forms of abuse have been higher. Díaz investigated the incidence of domestic violence among the older patients admitted to various hospital services in a Matanzas Province hospital over a one-year period (June 2008–June 2009). In a sample of 50 older adults, psychological abuse was also the most common, at 86%; 50% reported being victims of financial violence since their relatives controlled their pensions. Some 36% reported suffering physical violence, primarily by shoving or slapping that leaves no evidence. Sexual abuse was identified by 30% of those surveyed, although the author did not indicate how this was manifest.[17] In our study we identified only one participant as a victim of sexual abuse, manifested mainly through unwanted touching.

Several studies have shown that, although an individual’s family forms his or her main support network from birth, it is these same family members who most commonly exercise violence.[3,5,25] As in other research,[26–28] we found that it was the closest family members (generally younger) who most commonly abused older adults.

Regardless of type, abuse is based on exercise of power by use of force—whether physical, psychological, financial, social or other—and there is always someone above and someone below, whether really or symbolically, playing traditionally complementary roles: parent–child, man–women, employer–employee, young–old.[16]

A literature review found several theories seeking to explain this pattern:

- Caregiver stress levels: It has been proposed that drug abuse, violent behavior, low income levels, etc., can lead to caregiver stress, which can culminate in rage and violence.[29,30]

- Theory of transgenerational violence: This posits that family violence is a learned behavior transmitted from generation to generation when a child who experienced abuse by a relative becomes an abuser in adulthood.[31]

- Theory of psychopathology: This purports that personality disorders, mental illness, and cognitive developmental delay are underlying causes of abusive behavior.[16,29]

Of course, these theories are not mutually exclusive and their interactions should be assessed to examine the factors leading to abuse. In our context, we may observe that an older person’s dependency and illness can become risk factors for abuse when coupled with caregiver overload. Globally, it has been noted that the combination of illness and dependency and resulting burden can become too much; even when caregivers are committed to caring for their relative, over time they may become exhausted with other worries (including children, work, financial pressures, etc.), which can wear them down and put them at risk of abusing the person whose care is entrusted to them.[1]

The role of caregiver is not a minor task, and burnout can develop. Rodríguez-Blanco proposed that overload (leading to burnout) deteriorates the mental, social and physical health of caregivers, who may display anxious-depressive symptoms, increased social isolation, decline of family finances, greater general morbidity and even higher mortality compared with a non-overloaded population. Caregivers tend not to seek medical help, postponing their own problems while giving priority to those of their dependent family member.[25]

Curiously, this failure to seek help also applies to older adults who are victims of abuse, often remaining silent without reporting the problem.[25] In our research, many study participants referred to their fear and shame about public exposure. Other authors have also cited these reasons, as well as reluctance to disturb the family status quo, fear of reprisal or losing the perpetrator’s affection, and physical or mental inability to seek help.[3,13] Analysis of the characteristics of the older adults identified as victims of abuse and the family dynamics of these victims highlights the vital importance of the primary care health worker’s role to prevent, identify and intervene to stop domestic elder abuse.

In the Cuban context of a universal health system with strong primary care, the family physician—practicing in every Cuban neighborhood and in rural districts—should be able to identify domestic violence in a prompt and timely manner (based on detection of risk factors), enabling early and effective intervention. It has been shown that, whether physical signs are visible or not, asking about abuse simply and directly, without being judgmental or threatening, will increase the likelihood of obtaining a reliable history.[15]

Given this level of responsibility, falling not only on the family doctor and nurse, but also on the basic work group that includes various specialists from the community polyclinic, we recommend that these health professionals receive further training to improve their ability to identify signs and symptoms of abuse, since they are the ones who have the closest relationship with older adults in their communities.

This can be carried out under the aegis of the Comprehensive Older Adult Health Care Program, led by the Ministry of Public Health, which oversees the efforts towards healthy aging that began decades ago.[32] The Program’s essential aim, in fact, is to help raise the level of health and degree of satisfaction and quality of life of older adults through preventive, promotion, assistance and rehabilitative activities carried out by the National Public Health System in intersectoral coordination with other government agencies and organizations involved in such attention, conscious that the main actors are the families, communities and older adults themselves, most able to identify local solutions to their problems.[33]

Such a multidisciplinary and inter-institutional approach is a strength of the Program and the unified public health system,[20,21] enabling a comprehensive assessment of older adults in the context of their daily lives, detection of early signs of domestic abuse or violence, and implementation of solutions. This health care structure, once again relying on the neighborhood family doctor-and-nurse program supported by the community polyclinic, also facilitates development of community education strategies to raise awareness of the problem.

Our study’s main limitation is that all participants interviewed were from only one family doctor-and-nurse office, which limited study size and generalizability. The authors’ chief recommendation is to replicate the study throughout the entire polyclinic catchment area and in the three other polyclinics in the Marianao Municipality (with all victims identified receiving treatment and followup).

CONCLUSION

Psychological abuse and disrespect for personal space are by far the predominant types of elder abuse in this population. The finding that substantial numbers of older adults are victims of domestic abuse brings to light a hitherto insufficiently addressed issue in our community. More research is needed to deepen understanding of the scope and causes of the problem to inform prevention and management strategies in the Carlos Manuel Portuondo University Polyclinic catchment area and health areas in Cuba.

References

- World Health Organization. Informe Mundial sobre Violencia y la Salud. El maltrato de las personas mayores. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Chapter 5. p. 135–6. Spanish.

- Adams Y. Maltrato en el adulto mayor institucionalizado. Realidad e invisibilidad. Rev Med Clin Condes. 2012 Jan;23(1):84–90. Spanish.

- Valdés Rodríguez E, Guevara de León T, Nepomuceno Padilla N. Comportamiento de los malos tratos al adulto mayor. Medicentro. 2011;15(2):100–5. Spanish.

- Cano SM, Garzón MO, Segura AM, Cardona D. Factores asociados al maltrato del adulto mayor de Antioquia, 2012. Rev Facultad Nac Salud Pública [Internet]. 2015 Jan–Apr [cited 2015 Mar 21];33(1):67–74. Available from: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/120/12033879009.pdf. Spanish.

- Pérez Nájera C. Análisis del fenómeno de la violencia contra los ancianos. Rev Crim [Internet]. 2010 Jul–Dec [cited 2012 May 20];52(2):55–75. Available from: http://oasportal.policia.gov.co/imagenes_ponal/dijin/revista_criminalidad/vol52_2/03analisis.html. Spanish.

- Fernández-Alonso MC, Herrero-Velázquez S. Maltrato en el anciano. Posibilidades de intervención desde la atención primaria (II). Aten Primaria. 2006 Feb 15;37(2):113–5. Spanish.

- World Health Organization. Informe Mundial sobre la Violencia y la Salud. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. p. 2. Spanish.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU). Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2012. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2013 Apr. 190 p. Spanish.

- Escalona JR, Rodríguez R, Pérez R. La violencia psicológica al anciano en la familia. Psicol Am Latina [Internet]. 2009 Nov [cited 2015 Mar 21];18. Available from: http://www.psicolatina.org/18/vilencia.html. Spanish.

- Gómez Guerra DB, Valdés Vento AC, Arteaga Prado Y, Casanova Moreno MC, Barrabe AM. Caracterización del maltrato a ancianos: Consejo Popular Capitán San Luis, Pinar del Río. Rev Ciencias Médicas Pinar del Río [Internet]. 2010 Apr–Jun [cited 2013 Jun 15];14(2). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1561-31942010000200005. Spanish.

- Griñán Peralta IA, Cremé Lobaina E, Matos Lobaina C. Maltrato intrafamiliar en adultos mayores de un área de salud. MEDISAN [Internet]. 2012 Aug [cited 2013 Jun 15];16(8):1241–8. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1029-30192012000800008&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es. Spanish.

- World Health Organization. Declaración de Toronto para la prevención global del maltrato a personas mayores. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Spanish.

- García Pérez T. Caracterización sociopsicológica de la violencia intrafamiliar en Ciudad de la Habana para una propuesta de intervención [thesis]. [Havana]: Comandante Manuel Fajardo School of Medicine; 2006. Spanish.

- Pérez Nájera C. Violencia sobre el adulto mayor. Estrategia para reducir la victimización en el municipio de Ciego de Ávila [thesis] [Internet]. [Havana]: University of Havana; 2012 Apr [cited 2012 Aug 20]. 197 p. Available from: http://tesis.repo.sld.cu/514/. Spanish.

- Couso Seoane C, Zamora Anglada M, Puron Iglesias I, Del Pino Boytel IA. La bioética y los problemas del adulto mayor. MEDISAN. 1998;2(3):30–5. Spanish.

- Díaz López R, Arencibia Márquez F. Comportamiento de la violencia intrafamiliar en asistentes a la consulta de psicología. Rev Méd Electrón [Internet]. 2010 Mar–Apr [cited 2012 May 20];32(2). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1684-18242010000200004&script=sci_arttext. Spanish.

- Díaz López RC, Llerena Álvarez A. Principales manifestaciones de la violencia intrafamiliar en pacientes de la tercera edad, como factor de riesgo para la conservación de la salud. Hospital Universitario Clínico Quirúrgico Comandante Faustino Pérez Hernández. Junio 2008-Junio 2009. Rev Méd Electrón [Internet]. 2010 Jul–Aug [cited 2013 May 7];32(4). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1684-18242010000400008. Spanish.

- Mirabal López E, Alsina Morfa CA. Comportamiento del maltrato en el adulto mayor del ASIC “Simón Bolívar” en el año 2005. Rev Cubana Tecnol Salud [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2013 May 7];3(2). Available from: http://www.revtecnologia.sld.cu/index.php/tec/article/viewArticle/57. Spanish.

- Centro Ecuatoriano para la Promoción y Atención de la Mujer (EC). Imaginarios urbanos y violencia intrafamiliar. Quito: Centro Ecuatoriano para la Promoción y Atención de la Mujer (EC); 2000. p. 60–2. Spanish.

- Enamorado Tamayo AL, García Blanco S. Programa educativo ante la violencia intrafamiliar en el adulto mayor, 2010 [Internet]. Proceedings of the X Seminario Internacional de Atención Primaria de Salud-Versión Virtual. 2012. Havana, 2012. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2012 [cited 2013 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.cimfcuba2012.sld.cu/index.php/xseminarioAPS/2012/paper/viewPaper/81. Spanish.

- Márquez Reyes MA, Arvizu Iglesias R. Perfil de la violencia familiar en el anciano: experiencia en 680 pacientes mexicanos. Arch Med Familiar. 2009 Oct–Dec;11(4):167–70. Spanish.

- Mendo Alcolea N, Infante Tavío NI, Lamote Moya SE, Núñez Beri SJ, Freyre Soler J. Evaluación del maltrato en ancianos pertenecientes a un policlínico universitario. MEDISAN [Internet]. 2012 Mar [cited 2012 May 20];16(3):364–70. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1029-30192012000300008&script=sci_arttext. Spanish.

- Bayarre Vea HD, Pérez Piñero J, Menéndez Jiménez J. Las transiciones demográfica y epidemiológica y la calidad de vida objetiva en la tercera edad. GeroInfo [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2009 Sep 10];1(3). Available from: http://www.redadultosmayores.com.ar/buscador/files/DEMOG037_BAYARREVEA.pdf. Spanish.

- United Nations General Assembly. A/RES/46/91 Implementation of Plan of Action on Ageing and related activities [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 1991 Dec 16 [cited 2012 May 20]. Available from: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/46/a46r091.htm

- Rodríguez Blanco L, Sotolongo Arró O, Luberta Noy G, Calvo Rodríguez M. Violencia sobre personas de la tercera edad con demencia. Policlínico Cristóbal Labra, La Lisa. 2010. Rev Habanera Ciencias Médicas. 2012;11(5):709–26. Spanish.

- Gómez Guerra DB, Casanova Moreno MC, Trasancos Delgado M, Álvarez Bencomo O. Maltrato a los adultos mayores. Consejo Popular Capitán San Luis. Marzo 2011 [Internet]. Proceedings of Cuba Salud 2012. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2012 [cited 2013 Jan 5]. Available from: http://www.convencionsalud2012.sld.cu/index.php/convencionsalud/2012/paper/viewPaper/1209. Spanish.

- Trilles Solves R, Bellido Rodríguez MC, Peris Salas MC. Estudio de una realidad social en España: Envejecimiento de la población y formas de violencia contra los ancianos [Internet]. Proceedings of Interpsiquis 2013. Madrid: Interpsiquis; 2013 [cited 2013]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10401/5958. Spanish.

- Fernández González P, Socarrás Plutín E, González Velázquez LC, Nápoles Castillo M, Díaz Téllez R. Violencia intrafamiliar en el sector venezolano Las Tunitas. MEDISAN [Internet]. 2012;16(7). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1029-30192012000700010&script=sci_arttext. Spanish.

- Iborra Marmolejo I. Maltrato de personas mayores en la familia en España. Valencia, Centro Reina Sofía. Serie Documentos, No. 14 [Internet]. Valencia: Fundación de la Comunitat Valenciana para el Estudio de la Violencia; 2008 Jun [cited 2009 Apr 5]. 182 p. Available from: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/Violencia_Genero_Ficheros_Maltrato_personas_mayores.pdf. Spanish.

- Brookoff D, O´Brion KK, Cook CS, Thompson TD, Willians C. Characteristics of participants in domestic violence. Assessment at the scene of domestic assault. JAMA. 1997 May 7;277(17):1369–73.

- Boszormenyi-Nagy I. Visión Dialéctica de la Terapia Familiar Intergeneracional. In: Terapia Familiar 2. Estructura, Patología y Terapéutica del Grupo familiar. Buenos Aires: Editorial ACE; 1978. 229 p. Spanish.

- Duran Gondar A, Chávez Negrín E. Una sociedad que envejece: restos y perspectivas. TEMAS. 1998;14:57–68. Spanish.

- Ministry of Public Health (CU). Programa de atención integral al adulto mayor. Sub-programa de atención comunitaria. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU). Spanish.

THE AUTHORS

Victoria C. Ribot Reyes (Corresponding author: victoriaribot@infomed.sld.cu), dual specialist in family medicine and psychiatry with master’s degrees in bioethics and healthy aging. Assistant professor, Interdisciplinary Community Health Complex, Marianao Municipality, Havana, Cuba.

Elena Rousseaux Mola, family physician. Instructor, Carlos Manuel Portuondo University Polyclinic (PUCMP), Havana, Cuba.

Teresita C. García Pérez, psychiatrist with doctorate in medical sciences. Associate professor, Joaquín Albarrán Medical–Surgical Teaching Hospital (HDCQJA), Havana, Cuba.

Emilio Arteaga Pérez, psychiatrist. Instructor, HDCQJA, Havana, Cuba.

Marta E. Ramos Arteaga, family physician. Assistant professor, PUCMP, Havana, Cuba.

Maritza Alfonso Romero, family physician with master’s degree in medical education. Associate professor, PUCMP, Havana, Cuba.

Submitted: June 05, 2013 Approved: April 11, 2015 Disclosures: None