ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION There is a tendency among women today to delay the age at which they have their first child or subsequent children. This creates a dilemma for couples, since health professionals tend to counsel against pregnancy in women aged ≥40 years without considering their reproductive potential and their ability to and likelihood of conceiving and carrying to term a healthy newborn at little or no risk.

OBJECTIVEAssess hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function in menopausal women in Havana, to evaluate relevance to reproductive potential.

METHODS A retrospective study was conducted from March 2006 through March 2008 of 230 healthy women aged 40–59 years seen in the Menopause and Osteoporosis Clinic in Havana, Cuba. Chart review yielded data on current age, stage of climacteric and hormone levels expressed in means and standard deviations: serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol and testosterone. Analysis of variance was used for assesment by age group and stage of menopause (eumenorrheic, perimenopausal and postmenopausal), with a p value of <0.05 set as significance level.

RESULTS Mean serum hormone levels in eumenorrheic women were: FSH 6.97 IU/L, LH 4.23 IU/L and estradiol 314 pmol/L; in perimenopausal women: FSH 34.69 IU/L, LH 20.78 IU/L and estradiol 201 pmol/L; and in postmenopausal women: FSH 75.43 IU/L, LH 37.59 IU/L and estradiol 117 pmol/L (p <0.05 for difference between eumenorrheic and postmenopausal women). There was a progressive increase in FSH and LH and a decline in estradiol with older age. There was no significant difference in testosterone levels by age or stage of menopause.

CONCLUSIONS Menstrual cycle and hormonal levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis should be considered in addition to chronological age when determining reproductive potential in women aged 40–59 years.

KEYWORDS: Hormones, hypothalamo-hypophyseal system, luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, estradiol, testosterone, sex hormones, infertility, female, middle age, menopause, fertility, climacteric, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

During the second half of the 20th century, a demographic transition took place, characterized by a decline in mortality among older persons, lower birth rates and delay of first childbirth, especially in so-called developed countries.[1] The latter phenomena could result from a convergence of social factors, among them women’s need to attain economic independence and a certain professional status before deciding to have their first child; remarriage or second partnerships, resulting in the second or third pregnancy coming many years after the first; and finally, technology development, especially assisted reproductive technologies, giving hope to couples who for years had been receiving infertility treatment without success.[1–4]

In Cuba, furthermore, the period of acute economic hardship during the 1990s—known as the Special Period—[5] was also a factor leading many couples to delay procreation or renounce it altogether. When socioeconomic conditions improved, both men and women were confronted with the problem of aging gonadal function, women more so than men.[2]

These demographic conditions and individual situations resulted in a decline in replacement population that persists to this day in Cuba. This becomes an issue for government decisionmakers and health care providers, challenged to help increase the population by encouraging healthy and responsible motherhood in young women, and also to determine more precisely the effects of ovarian aging on the reproductive potential of middle-aged women (aged 35–50 years),[6] who account for roughly 12% of the Cuban population.[7] That is, their ability to and likelihood of conceiving and carrying to term a healthy newborn.

Aging is a continuum that begins with the union of egg and sperm and ends with death, affecting each organ and system in a specific manner. Ovarian follicles are present in utero. Menarche heralds the onset of the female reproductive phase, a cyclical process of follicular growth and maturation leading to ovulation, governed by the hypothalamus and pituitary glands through the release of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).

From the age of 35 years, women begin to undergo physiological changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function. These changes are part of the stage known as climacteric, culminating in the definitive end of new ovarian follicle maturation, with attendant loss of reproductive function and menstruation (menopause). Thus, women past their mid-30s have greater difficulty conceiving (tending more towards infertility), and of achieving a normal pregnancy and delivery (greater obstetric risk). This often leads health professionals in Cuba to overestimate risks and counsel against trying to conceive without considering a woman’s biological potential.[6]

As women go through the stages of climacteric, serum FSH and LH increase in response to gradual loss of follicular maturation, which in turn produces a drop in estradiol levels.[8–15] There are no objective signs enabling prediction of the age at which menopause will occur, so it is hard to determine with any certainty an individual woman’s reproductive potential—ability to ovulate and conceive—based solely on her chronological age.

To facilitate better decision-making by clinicians in Cuba, given the frequency with which women aged ≥40 years consult them about the possibility of having children, we set out to study the reproductive potential of women in this age group. Hence, the objective is to assess hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function in women aged 40–59 years in Havana.

METHODS

A descriptive retrospective study of a group of women in Havana was conducted using data from March 2006 through March 2008. In order to describe hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function or reproductive hormone profile, we reviewed 243 medical charts of apparently healthy women aged 40–59 years seen in the Menopause and Osteoporosis Clinic (ClimOs, the Spanish acronym) of the National Endocrinology Institute (INEN, the Spanish acronym) during that period.

A total of 230 charts met inclusion criteria (no medical or surgical condition that would compromise ovarian function, no use of hormonal contraceptives and hormone levels available). Under the ClimOs protocol, all women are interviewed to ascertain presence or absence of chronic diseases (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cancer) or other illnesses; date of last menstrual period, changes in their menstrual cycle and menopausal symptoms (palpitations, hot flashes, sweats); and current age. Their levels of FSH, LH, estradiol and testosterone are then tested to determine hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function. Tests are performed in the morning between days 3 and 5 of the menstrual cycle in women who have regular periods and at any time for those with amenorrhea.

All hormone tests were done in INEN laboratories[16] using the following reference values: for women with regular periods (eumenorrheic): estradiol: 209–833 pmol/L and testosterone: 0.24–2.253 nmol/L (both determined by radioimmunoassay or RIA); FSH: 0.6– 9.5 IU/L and LH: 0.7–9.0 IU/L (determined by immunoradiometric assay or IRMA). For postmenopausal women: estradiol: <82 pmol/mL; testosterone: 0.6–.2.5 nmol /L; FSH: 30–135 IU/L; LH: 13–80 IU/L.

Analysis Results were analyzed by age group and menopausal stage. Age groups were 40–44; 45–49; 50–54 and 55–59 years. Menopausal stages were eumenorrheic or premenopausal (no changes reported in menstrual cycle, n = 43), perimenopausal (vasomotor symptoms or menstrual cycle changes reported, n = 60) and postmenopausal (amenorrhea of >1 year). This last was divided into early (≤5 years postmenopause, n = 80) and late (>5 years, n = 60) stages.[17] Mean serum levels were calculated for all hormones and analysis of variance used to compare groups, with a p value of <0.05 as significance cutoff.

Ethics procedures The INEN ethics committee approved the study conditioned on due protection of confidentiality and anonymity of women whose charts were reviewed.

RESULTS

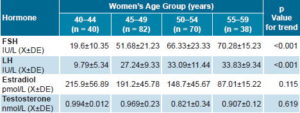

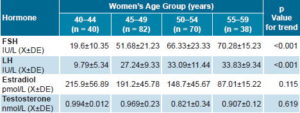

Table 1 shows mean serum hormone values by age group. Serum levels rose monotonically with increasing age for FSH (p <0.001) and LH (p <0.001). Estradiol levels fell over the same period; although the overall trend was not significant (p = 0.115), there was a statistically significant difference between the youngest and oldest groups. Testosterone levels remained unchanged (p = 0.619) (Table 1).

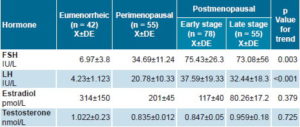

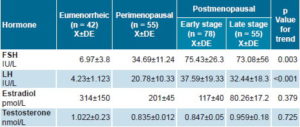

In terms of menopausal stage, FSH and LH values began to increase in the perimenopausal period (p = 0.003 and 0.000, respectively), while estradiol levels fell, again without statistical significance. Testosterone levels remained unchanged throughout menopause (p = 0.725) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The onset of climacteric is characterized by the need for higher levels of FSH to create a follicle capable of producing adequate amounts of estradiol and releasing an egg, and with it the possibility of fertilization and subsequent gestation. From age 40, the number of follicles continues to decline along with their competence or functional capacity, requiring increasing levels of FSH (>40IU/L) to achieve follicular maturity and ovulation. This latter event is not always achieved (anovulation occurs), expressed as changes in the menstrual cycle. An interesting and perhaps paradoxical phenomenon in this stage is that it occasionally produces an excessively high peak in LH secretion, and with it, probable multiple ovulations, which may explain the increase in twins gestations seen in this age group.[18,19]

Table 1: Hormone values of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis by age group, Havana, 2006–2008

Table 2: Hormone values of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis by menopausal stage, Havana, 2006–2008

Analyzing the results of serum hormone values to evaluate hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function, taking age into account, the physiological phenomena mentioned above were confirmed. That is, as age increased, serum FSH and LH levels rose and estradiol levels fell, although it was not until ages 55–59 years that the hormone pattern became typical of the postmenopausal stage, leading to the assumption that from 40 to 50 years, women are in different stages of climacteric. The average age of menopause in Cuba is 48.[4,16]

Taking the characteristics of the menstrual cycle into account, it was confirmed that eumenorrheic women had hormonal levels characteristic of the early follicular growth phase and therefore would be expected to ovulate and maintain their reproductive capacity, while those who reported amenorrhea of five years or more had a hormone pattern consistent with that reported for the postmenopausal stage. On the other hand, women in the perimenopausal stage had average hormone values that were not typical of those reported for the pre- or postmenopausal stages.[20] These results confirm the findings of many investigators[10,11,18,19,21–25] who report characteristics of female gonadal axis function during climacteric, leading to the assertion that in that stage of a woman’s life, it is more important to consider the characteristics of the menstrual cycle than chronological age when attempting to identify reproductive potential—an opinion that we share.

We are unaware of national studies by other authors[26] that describe the hormonal pattern of Cuban women in climacteric, since the report by R Padrón et al. studied only women aged ≥60 years.[27]

In Cuba, the female fertility rate decreases with age, as observed in data from the Health Statistics Yearbook of the Ministry of Public Health,[7] showing that the fertility rate (per 1000 women) in those aged 35–39 years was 17.1 in 1995 and 21.8 in 2007, while for the same years, it was 2.5 and 3.9 in women aged 40–44 years, and 0.5 and 0.2 in women aged 45–49. From these results, we conclude and suggest to clinicians that during climacteric, a woman’s age should not be the only criterion for ruling out a probable spontaneous pregnancy or recommending assisted reproductive techniques for women who request them.

The undesirable consequences of pregnancy most commonly reported in both adolescents and women aged ≥40 years are miscarriage, gestational diabetes and severe preeclampsia.[8,9,27–29] In particular, the national and international literature reports the following increases in complications in the older age group compared to younger women: miscarriage (40% vs. 15% in women aged <40 years); gestational diabetes (7.7% vs. 5%), and preeclampsia in up to 9.7%.[8,9,27–29] However, some studies indicate a lower frequency of gestational diabetes.[28,29] We therefore consider it important for physicians to perform an exhaustive clinical assessment and obtain a hormone profile before counseling women aged >40 years about reproduction.

CONCLUSIONS

Without minimizing potential risks (maternal and fetal) associated with older age in pregnancy, we conclude that a woman’s chronological age is a necessary but insufficient criterion for determining her reproductive potential in middle age. We therefore recommend that clinicians not counsel women against pregnancy solely because of the mother’s chronological age, especially women aged 40–44 years, without performing a clinical and hormonal assessment.