INTRODUCTION

The marked increase in the number of people with diabetes mellitus (DM) over the last few decades is due, in essence, to an aging population and to lifestyles associated with urbanization.[1,2] International Diabetes Federation 2014 estimates show a worldwide prevalence of 8.3% and predict a 53% increase by 2035. In 2014, DM caused 4.9 million deaths.[3]

Ninety percent of diabetes cases are type 2 (DM2),[4] influenced by complex interactions among factors such as genetic and epigenetic predisposition, environmental exposures and lifestyles.[2] Until recently, DM2 was considered exclusively a disease of adults, but in the past two decades, increasing numbers of cases have been seen in children and adolescents in numerous countries.[5,6]

Overweight (BMI ≥25 and <30) and obesity (BMI ≥30) are the best predictors of DM2.[7−9] Increased DM prevalence is directly associated with increased frequency of both.[2,4,8,9] Over 80% of children and adolescents with DM2 are overweight and some 40% are clinically obese.[10]

At the same time, incidence of type 1 DM, which chiefly appears at younger ages, has been increasing. Two international collaborations, DIAMOND[11] and EURODIAB,[12] have identified, although with geographical variations, a 3% annual increase in incidence, particularly due to cases in very young children. This increase is less clearly explained than that of DM2; several hypotheses have been developed, none conclusive.[4,13,14]

Needs for treatment, systematic blood glucose monitoring and diet impose a considerable economic burden on families and health systems. Furthermore, coping with a disease that involves lifelong behavioral changes is more difficult in children, who are still emotionally and intellectually immature, negatively influencing adherence to treatment.[3,15] Early onset of diabetes increases risk of complications in adulthood and consequently, premature death.[16,17] An additional challenge lies in the fact that a greater number of women are entering their childbearing years with diabetes, which has a negative impact on pregnancy outcomes.[18]

Systematic estimates of the global, regional and national burden of diabetes[1,2,11,12,19] tend to use measures of incidence, prevalence and mortality. However, isolated analysis of any of these is complex and of little help in setting priorities and allocating resources.

The 1990 Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) provided estimates of the burden of 107 diseases or injuries and 10 risk factors for 8 geographic regions around the world, to inform health priorities, policymaking and resource allocation by governmental and nongovernmental agencies.[20] An indicator introduced in GBD 1990, disability-adjusted life years (DALY), has since been used by many research studies to report disease burden for a wide range of diseases,[21–24] including DM.[25–29]

DALY, an indicator rarely used in Cuba, integrates years of life lost due to premature death (termed potential years of life lost, or PYLL), and years of life “lost” by virtue of living with suboptimal quality of life (years lived with disability, or YLD).[20] Between 1990 and 2010, DM’s all-age DALY rate increased by 30% worldwide.[24]

In Cuba, DM prevalence in the general population increased from 23.6/1000 population in 2000[30] to 55.7/1000 in 2014[31] with an increase in younger ages also, greater beginning in the group aged 10–14 years, in which the rate increased from 0.7 to 1.5/1000 from 2000 to 2014. DM prevalence in the group aged 15–24 years was 3.8/1000 in 2000, and 5.4 and 13.8/1000 in the groups aged 15–18 and 19–24 years, respectively, in 2014.[30,31] Cuba’s morbidity and mortality statistics do not distinguish between types of diabetes, thus it is not possible to attribute this rise to one type in particular.

DM has remained among the top ten causes of death in recent decades, with an increase in the age-standardized rate from 10.4 to 11.2/100,000 from 2000 to 2014.[30,31]

A literature review identified only two Cuban studies, conducted by the author of this paper, which quantified diabetes burden in terms of DALYs. The first included all ages and both sexes, for the period 1990–2005;[32] and the second, women of childbearing age, for the period 1990–2010.[33] Both showed an increase in DALY as a consequence of diabetes, primarily due to the disability component.

Given the particular complexity of diabetes at young ages and its epidemiological situation globally and nationally, its magnitude in the Cuban population needs to be determined using different methodologies, which will contribute more and better information to orient health policies. The objective of this paper is to describe the trend in diabetes burden in the Cuban population aged <20 years, from 1990 to 2010, in terms of disability-adjusted life years.

METHODS

A national, retrospective descriptive epidemiological study was done of DM burden in the population aged <20 years. The years analyzed were 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005 and 2010. Every fifth year was considered sufficient to demonstrate changes in DM burden trend over two decades.

Mortality burden estimate Calculations were based on total deaths in Cuba for ages 0–19 years in which diabetes was recorded as underlying cause of death. The Ministry of Public Health’s National Statistics Division (DNE-MINSAP) provided data from its mortality database.

PYLL rates per 100,000 population were calculated, using the usual method adapted by WHO[20] and considering as maximum lifespan the estimated life expectancy for the periods corresponding to each of the years included. The following International Classification of Diseases codes were considered:

- For 1990, 1995 and 2000; ICD-9 codes 250.0–250.9

- For 2005 and 2010; ICD-10 codes E10–E14

Estimated life expectancy by five-year age group was obtained from Cuba’s National Statistics Bureau.

Disability burden estimate The DISMOD II[34] program was used to obtain incidence and average duration, by inputting mortality, prevalence and remission data. Mortality and prevalence data were obtained from mortality databases and DNE-MINSAP primary care registries for continuous assessment and risk evaluation (CARE), respectively. Because DM is a virtually incurable disease, we assigned a value of zero to remission. YLD were obtained from the product of diabetes incidence, average duration (obtained from DISMOD II output) and severity.

DISMOD II is open-source software used to estimate six internally consistent epidemiological indicators, requiring a minimum of at least three input variables from registries. It estimates the following epidemiological indicators: incidence, prevalence, mortality, remission, average age at onset and average duration.[34] The program was developed as part of the 1990 GBD,[20] to provide more reliable estimates (than from national and regional registries) to calculate disability burden.

Severity values To compute YLD associated with diabetes and its complications (diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, diabetic neuropathy, diabetic foot, amputation, ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease) as a whole (to encompass diabetes itself—i.e., without complications and all of its complications) it was necessary to obtain an average severity, based on the severity of uncomplicated diabetes and the severities of each of the different complications considered. Weighting was based on prevalence of each condition. Sources for obtaining prevalence and severity values, as well as the methodology for obtaining weighted severity are described in a previous article, from which we took the resulting severity value (0.17).[35] Rates for YLD per 100,000 population were calculated.

Overall burden estimate DALY are the sum of PYLL and YLD. DALY rates (per 100,000 population) were calculated, as were the proportions of DALY corresponding to disability and to premature death.

To describe the trend, the percent relative change from the first to the last year in the series was calculated for each of three indicators.

Ethics All study data were retrieved from registries, with data management procedures ensuring individual confidentiality. The study was approved by the National Endocrinology Institute’s Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

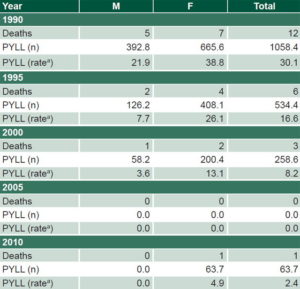

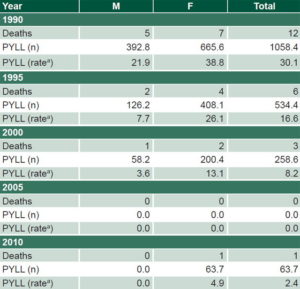

From 1990 to 2010, PYLL due to diabetes declined in Cuban children and adolescents of both sexes. There were zero PYLL in both sexes in 2005, and in boys in 2010. The overall PYLL rate dropped 92%. Rates were higher in girls, although the rate of 4.9/100,000 in 2010 corresponded to a single death (Table 1).

Table 2 shows losses of healthy life from disability. The YLD rate increased during the period, more than doubling the 1990 rates in 2010 in both sexes (increases of 134.6% in boys and 156.4% in girls), with the most notable increase from 2005 to 2010. The overall rate increased 145.9%.

DALY rates, in Table 3, show the same trend as for YLD, with an overall increase in 2010 of 105.4%, greater in girls (108.1%, vs. 102.3% in boys).

Figure 1 displays the contribution of each component (PYLL and YLD) to DALY by sex, showing a decrease in the contribution of premature death with a corresponding increase in that of disability. In 2005 and 2010, 100% of DALY originated from disability in boys, and 100% and 99% in girls. The proportion of DALY due to premature death was greater in girls in four of the five years studied.

Table 1: Diabetes-related PYLL in Cuban children and adolescents, 1990–2010

aper 100,000 PYLL: potential years of life lost

Table 2: Diabetes-related YLD in Cuban children and adolescents, 1990–2010

aFrom DISMOD II bper 100,000 YLD: years lived with disability

Table 3: Diabetes-related DALY in Cuban children and adolescents, 1990–2010*

*per 100,000 DALY: disability-adjusted life years

Figure 1: Contribution of disability and premature mortality to Diabetes-related DALY in Cuban children and adolescents, by sex, 1990–2010

DALY: disability-adjusted life years PYLL: potential years of life lost YLD: years lived with disability

DISCUSSION

The decrease in PYLL due to diabetes from 1990 to 2010 in the study population is consistent with results of a previous study that described the trend in age of death from diabetes in Cuba in the same period. The study brought to light a shift in deaths to older ages, with average ages of death from DM in 2010 of 70.2 years in men and 72.2 years in women. Some 16.2% of deaths occurred in the group aged ≥85 years, compared to only 9.9% in 1990.[19] A more recent study reported a decrease in PYLL due to DM in Cuban women of childbearing age in the same period.[33]

The two previous studies and results of this study coincide in showing a favorable trend in diabetes mortality in Cuba, with regard to age of death: fewer deaths are occurring in children, adolescents and women of childbearing age,[33] and a greater proportion at advanced ages.[19]

Worldwide, DM rose from 27th to 19th place as a cause of premature death from 1990 to 2010, with a 70% increase in PYLL in those 20 years,[36] and the International Diabetes Federation reported that 50% of diabetes deaths in the world in 2014 occurred in people aged <60 years.[3]

According to estimates from the 2013 GBD, the contribution of DM to all deaths in the population aged <5 years in Cuba is 0.026%. In the world, it is 0.071%; in the USA, 0.14%; in Mexico, 0.24%; in Brazil, 0.17%; and in Spain, 0.20%. The specific values for the group aged 5–14 years are 0.22% in Cuba and 0.25%, 0.52%, 0.71%, 0.71% and 0.38%, in the world, the USA, Mexico, Brazil and Spain, respectively. Likewise, the mortality rate in Cuba is lower for both age groups (0.029 and 0.042/100,000, respectively) compared with the US (0.19 and 0.069/100,000), Brazil (0.6 and 0.21/100,000) and Mexico (0.81 and 0.2/100,000). Spain also has higher DM mortality than Cuba in the group aged <5 years (0.14/100,000), but lower in the group aged 5–14 years (0.038/100,000). It is not possible to make comparisons for the group aged 15–19 years since the 2013 GBD does not report independent values for this age group.[37]

With regard to the mortality trend from 1990 to 2013, the 2013 GBD results are consistent with this study: annual decreases of 4.1% and 3.8% in age groups <5 and 5–14 years, respectively. Actual global values were lower (2.73% and 1.94%). The US and Mexico also had smaller decreases than Cuba, while Brazil’s increased by 0.042% for the age group 5–14 years, and Spain decreased slightly more than Cuba (4.6% and 3.9% for the two age groups, respectively).[37]

Cuba’s health system guarantees universal and free health services.[38,39] In the case of DM, this principle is embodied in the National Diabetes Program, created in 1975, which has increased in priority since 1992. The basic aims of this program are to reduce DM morbidity and mortality, reduce frequency and severity of complications and improve quality of life for people living with DM, through medical care, prevention, education and research.[40] In line with Cuban health policies, the Program includes specific actions targeting particularly vulnerable population groups, including children and adolescents. These include care for all diabetic children and adolescents by endocrinologists at secondary and tertiary care levels, interacting with primary health care providers;[40] school involvement in patient management;[40] free or subsidized drugs (insulin and others) and blood sugar monitoring equipment (glucometers and test strips);[38,39] and comprehensive, multidisciplinary care emphasizing education. Along these lines, annual “Camps for Children and Adolescents with Diabetes Mellitus” have had a great impact; providing diabetes education since 1993, they are currently held in most Cuban provinces.[41]

This study’s objectives and design do not permit an assertion that the favorable DM mortality trend in the population aged <20 years is a direct consequence of such policies and programs and the quality of their implementation, but it does support generating hypotheses to test in future studies. There is sufficient scientific evidence that proper management of diabetes using standardized protocols prevents complications and, consequently, premature death.[42]

The increased number of children and adolescents diagnosed with DM in recent decades in Cuba[30,31] and decreased diabetes mortality we observed in this population group have yielded an upward trend in YLD.

Unfortunately, Cuban morbidity and mortality statistics do not distinguish between diabetes types, which prevents linking increases in losses due to disability, and consequently in DALYs, reported in this paper, to a specific type. However, there is some evidence suggesting that DM2 has a predominant influence:

- increased prevalence (most notable starting at age 10 years),[30,31] which is consistent with patterns in other contexts,[37] and which is explained by physiological insulin resistance of puberty;

- its association with the increase in excess weight at these ages;[10,16] rising frequency of overweight and obesity in Cuban children and adolescents, and greater presence of lifestyles conducive to its development (high-calorie diets and inadequate physical activity);[43,44] and

- its relationship to excessive maternal weight.[2,3,44] The proportion of Cuban women who start pregnancy overweight or obese increased from 14.7% in 1997 to 27.1% in 2011.[43]

The increase in YLD and DALY rates could also, although to a lesser extent, be related to an increase in incidence of DM1, which rose with some fluctuations from 1.28/100,000 Cubans aged <15 years in 2000 to 2.18/100,000 in 2008.[45]

The increase in DM-related DALY we observed is consistent with reports for the general population. A previous Cuban study that included both sexes and all age groups found that from 1990 to 2005, the DALY rate rose from 520 to 660/100,000 in men and from 840 to 1120/100,000 in women, mainly due to the disability component.[32] Similarly, in women of childbearing age, the DALY rate increased from 494 to 1375/100,000 between 1990 and 2010, with an increase in the contribution of disability and the corresponding drop in mortality.[33]

Worldwide, the all-age DM-related DALY rate increased from 523 to 680/100,000 between 1990 and 2010. During the same period, DM rose from 29th to 14th place among all causes[24] and the DM-related YLD rate rose by 28.6%, from 234 to 301/100,000.[46] DM-related DALY show different patterns when comparing 2013 GBD estimates for the pediatric age group in Cuba and other countries. While the DALY rate for the group aged <5 years in Cuba was lower than that of the US, Mexico, Brazil and Spain, the DALY rate for the group aged 5–14 years was greater than the rate for these countries, except for Mexico, which had similar values. DM’s contribution to total DALY in the Cuban population aged 5–14 years (1.2%) is greater than seen globally and in the four other countries compared.[37]

The 2013 GBD reported a 0.34% annual increase in the DM-related DALY rate for Cuba between 1990 and 2013. There were decreases both globally and for the other four countries in the group aged <5 years, while DALY rates consistently rose in the group aged 5–14 years, with values of 1.33% annually for Mexico and Cuba, 1.69% for Brazil, with slighter increases globally and for Spain and the US.[37]

All of the foregoing supports the need for reliable estimates of diabetes burden in different population groups, in order to guide and evaluate policies aimed at early diagnosis and effective treatment, and also, with high priority, at prevention.

This study has several limitations. First, prevalence data used to calculate years of healthy life lost to disability come from national registries, making it impossible to rule out a certain margin of error. Second, analysis of mortality based on deaths in which diabetes was recorded as the underlying cause of death means that deaths in which diabetes was a contributing or direct cause of death were not included. Finally, severity values are inevitably subjective, even more so because they were not obtained specifically for the Cuban context. It was necessary to take severity values from studies in other contexts because Cuba does not have its own severity estimates for diabetes and its complications. Obtaining Cuban values, not only for diabetes and its complications, but also for many other diseases, should be the subject of future studies, as an essential first step for carrying out national disease burden studies.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first Cuban study to estimate diabetes burden (in terms of disability-adjusted life years) in the population aged <20 years. The particularities of diabetes in this population group give special meaning to its results. The frank downward trend in mortality reflects the comprehensiveness and quality of care for these patients. However, the increase in YLD, and consequently DALY, indicates the need to step up actions aimed at prevention, and to plan and allocate resources targeted to prevention and disease management in this population group. The results of this study are useful for design and implementation of programs and policies to continue to reduce DM burden in the pediatric population.