The world’s 1,691 medical schools and 5,492 nursing schools are not producing enough graduates to cover the massive global deficit of doctors, nurses, and midwives, reports the World Health Organization (WHO).[1] One scaling-up initiative addressing these critical shortages is Cuba’s Latin American Medical School (ELAM).

By August 2007, the ELAM had graduated 4,465 doctors in three graduations. [2] The graduates come from 29 low- and middle-income countries, in addition to nine graduates from minority and economically depressed communities in the United States. Most new graduates are already home, navigating each country’s respective laws regarding validation of foreign medical degrees. Authorities in countries including Argentina, the Dominican Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Guatemala, Haiti, Paraguay, the United States, and Venezuela already recognize the ELAM degree.[3]

Eight new doctors for underserved areas in the United States graduated from the ELAM in 2007 (from left): Melissa Barber, Toussaint Reynolds, Jose De Leon, Wing Wu, Carmen Landau, Teresa Thomas, Evelyn Erickson, and Kenya Bingham.

Photo credit Arnold Trujillo

Background

The ELAM, established in 1999 and currently enrolling 8,637 for all six medical school years,[4,5] emerged as a long-term response to the health crisis in Central America after Hurricanes Georges and Mitch devastated the region in 1998. These natural disasters and the ensuing health crises suddenly and graphically uncovered the precarious state of already weak health systems.

ELAM contributes to strengthening public health systems by training doctors to serve in shortage areas eventually replacing Cuban doctors currently working in those countries under Cuba’s international health cooperation program. Initiated in 1963 and expanded after the hurricanes, Cuba’s program now posts some 30,000 health professionals in over 60 poor countries.

The World Health Report 2006 outlined a working lifespan approach for training and retaining a global health workforce by focusing on strategies related to three work life phases: Entry, Work Years, and Exit. The central objective of the Entry Phase is to produce enough skilled, technically competent workers whose background, language, and social attributes make them accessible to diverse populations. It is precisely in this Entry Phase where the ELAM fits into the global health workforce puzzle.

Training & Retaining: ELAM in the Global Health Context

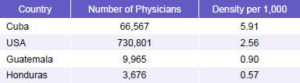

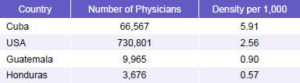

ELAM recruits students from Latin America, Africa, Asia and Oceania, with countries from the Western Hemisphere most heavily represented. The Western Hemisphere contains only 10% of the global burden of disease, yet almost 37% of the world’s health workers. Nevertheless, uneven distribution of these workers – both within regions and countries – leaves 125 million (25%) residents in Latin America and the Caribbean without permanent access to health care,[6] largely due to urban concentration of physicians; the availability of doctors in urban areas is eight to 10 times greater than in rural areas. In Human Development and Equity in Latin America and the Caribbean, López et al. found that 160,000 physicians, about 17%, would have to be redistributed in the region to attain equitable distribution.[7]

Table 1: Physician Density in Selected Countries

Source: World Health Organization, Working Together for Health 2006

Global distribution of health personnel is a complex issue driven by a constellation of factors such as international emigration of physicians, nurses, and other health workers, as well as intranational migrations from rural areas to urban centers.[ 8]

The socio-economic, ethnic, and linguistic profiles of students entering health professions both in industrialized and developing countries rarely reflect national diversity profiles, as students are disproportionately admitted from higher social classes and dominant ethnic groups.[1] This exacerbates the concentration of doctors in urban centers that offer middle-and upper-class lifestyles.

The ELAM recruitment strategy addresses such disparities: 75% of ELAM students come from low-income backgrounds and many from rural areas, with some 100 ethnic groups represented; notably, 51% of students are women. Outreach focuses on young people willing to make a commitment to return to work in their communities of origin or similar areas. The notion that graduates will be more likely to work in rural, underserved communities if they have their own roots there is supported by health policy studies. The Joint Learning Initiative (JLI) 2004 report notes: “Recruiting and selecting students from rural communities improves the odds that graduates will be willing to serve in rural placements.”[9]

Approximately 75%-80% of those initially enrolled go on to graduate, with the highest attrition rate during the first year.[10]

The workforce Entry Phase for ELAM graduates is conditioned by each country’s unique set of circumstances. According to ELAM officials, degree recognition is an evolving issue, with some bilateral governmental agreements already in place (e.g., Ecuador), while other accords have been reached with individual medical schools (e.g., Guatemala). In other cases like the United States, graduates must adhere to existing regulations for all foreign medical graduates.

Case I: Guatemala

There are 435 Guatemalan graduates from the three ELAM graduations. From the first graduating class in 2005, 133 (86%) were incorporated into Guatemala’s compulsory social service year for medical graduates.[11] Dr Jesus Oliva Leal, dean of the San Carlos University Medical School told MEDICC Review (MR) in an exclusive interview, “after careful analyses, conversations between the health ministries of both countries, the ELAM administration and our institution, it was decided ELAM graduates could practice in Guatemala after a year of hospitalbased social service.”

The year is expected to complement and enhance skills specific to Guatemala’s epidemiological characteristics and enhance care in hospitals with the greatest physician shortage. During their social service year, graduates can also enroll in the Family Medicine Residency program with Cuban faculty, offered by the Cuban Medical Team in Guatemala (and other countries) where Cuban physicians are posted. Fifty-seven percent of ELAM-trained doctors are pursuing this option, working in Guatemala’s most remote rural areas.

One such region in northern Guatemala is the predominantly rural and indigenous Alta Verapaz (pop. 776,000).[12] One Cuban Medical Team is working in the regional capital of Cobán, with a population 161,000, a poverty rate of 76%, and illiteracy rate of 39%.[13]

Dr Ana Sasuin, (ELAM class of 2005), completed her social service year and has entered family medicine residency training in Cobán, where infant mortality is 31 per 1,000 live births and maternal mortality is 223 per 100,000 live births.[13] Dr Sasuin said she wants to return to Cuba for a second residency in OB-GYN. Fellow family medicine resident, Dr Wenceslao Barrera, plans to do a surgical residency and return to the hospital near his native town of Asunción in Jutiapa province.

Dr Oliva was optimistic about the prospects for ELAM-trained Guatemalan doctors: “Although a country like Guatemala has many budgetary constraints,” he said, “the Ministry has pledged to hire the first cohort of graduates to work in the most underserved areas of the country.”

Dr Wenceslao Barrera examines a patient in Cobán, Guatemala. Photo credit Diane Appelbaum

Case II: The United States

Since the ELAM is accredited by the WHO, the United States recognizes the ELAM degree providing graduates follow the formal process for all foreign medical graduates, established and overseen by the Educational Commission for Medical Foreign Graduates (ECFMG). ELAM students take the US Medical Licensing Exams (USMLEs) and participate in the Residency Match Program. Dr Cedric Edwards, the school’s first US graduate, is currently pursuing a residency at New York’s Montefiore Medical Center. This July, eight new US doctors graduated, with exam preparation first on their agendas.

The majority of ELAM’s US graduates are from minority families, unable to afford the high cost of medical education, contrasting sharply with typical US medical student and graduate demographics. Sixty percent of US medical students come from families in the top 20% income bracket,[14] whereas only 20% come from the bottom 60%. Ethnic diversity is similarly compromised: Blacks and Hispanics/Latinos comprise only 6.4% of all graduating physicians from US medical schools, though these groups together represent 26% of the total population.[15]

Interviewed by MR, graduates expressed their commitment to work in their communities. Dr Melissa Barber said, “the place where I would love to practice is Bronx Lebanon Hospital in New York. That’s where I was born, where my daughter was born, and where my mother volunteered. I grew up around that hospital. In the long run, I’d like to open a community clinic, with a special focus on adolescent girls.” In another departure from the norm for US medical graduates, the majority of these graduates are seeking primary care residencies, like Dr Evelyn Erickson who plans to specialize in pediatrics and Dr Teresa Thomas who’s chosen family medicine.

The fact that ELAM medical education is free allows these graduates to start their careers debt-free; student debt repayment is cited as a determining factor in US graduates’ opting out of primary care in favor of better paying fields, resulting in shortages of primary care physicians in many parts of the United States.[7,16]

Case III: Honduras

Honduran ELAM graduates cannot yet formally practice within the national public health system – a source of frustration according to graduates interviewed in Havana. The Honduran press reported that the Council of Higher Education had decided in favor of recognizing the ELAM degree and validating the year of clinical clerkships done in Cuba.[17,18] However, the Medical Association has opposed the decision arguing that all foreign medical graduates in Honduras must do a year of clinical clerkships and another of social service in-country.

The situation is tense: earlier this year, a national strike of Honduran-trained medical residents and interns was called by the Medical Association to demand that ELAM graduates complete the clerkship and social service years. The strike lasted for 63 days, affecting hospitals nationwide.[19,20]

Dr Luther Castillo, ELAM graduate and civic leader from Honduras told MR that the Medical Association has presented an appeal to revoke or suspend recognition of the ELAM degree by the Council of Higher Education. The appeal automatically freezes all accreditation procedures, preventing graduates from working. Moving forward, the Superior Court has to decide whether the Council of Higher Education has acted according to the law. “We have incredible public support,” added Dr Castillo. “Grassroots organizations representing rural communities and Afro-Hondurans have protested to express their support for the Cuban-trained doctors.” As MR went to press, the Honduran situation remained unresolved.[21] Until the situation stabilizes, some ELAM graduates are taking advantage of pursuing a specialty in Cuba.

Dr Luther Castillo (ELAM class 2005), in front of the community hospital he and other Garifuna graduates are constructing with international cooperation in Ciriboya, the Honduran Mosquitia.

Cuba currently has some 30,000 health professionals volunteering in over 60 poor countries. Often, they are serving in the most remote communities, like this physician in the Garifuna village of Tocamacho, Honduras.

Photo credit Connie Field

Conclusion

ELAM is preparing doctors with critical skills for the global health workforce. In Working Together for Health, WHO says “countries [should] work together, as individual national strategies, however well conceived, are insufficient to deal with the realities of health workforce challenges today.”[1] ELAM is offering a unique opportunity, building a network of health professionals whose shared experience may lay a foundation for much needed international collaboration.

The extent to which these new doctors will be able to provide a long term response to their countries’ health needs, either by replacing the Cuban medical teams in the most remote regions or by becoming the first doctors in some areas of critical medical shortages, is a work in progress.

References

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health. Geneva, Switzerland; 2006.

- Dr Jorge Gonzalez Perez, Rector, Institute of Medical Sciences of Havana, Graduation Speech. July 24, 2007, Havana, Cuba.

- Personal communication with Dr Midalys Castilla, Dean of Academic Affairs on August 17, 2007.

- Dirección Nacional de Registros Médicos y Estadística MINSAP, La Habana, Cuba.

- For a detailed description of the ELAM, its curriculum and teaching methodology, see http://www.medicc.org/publications/ medicc_review/0805/index.html.

- Brito P. WHO/PAHO Presentation: The Decade of Human Resources: 2006 – 2015, Informatics Congress, Havana February 13, 2007.

- López C, Márquez M, Rojas Ochoa F. Human development and equity in Latin America and the Caribbean. MEDICC Review. 2005 Nov-Dec;7(9):21-9. Available from: http://www.medicc.org/ publications/medicc_review/0905/cubanmedical- literature-1.html.

- Bundred P, Martineau T, Kitchiner D. Factors affecting the global migration of health professionals Harvard Health Policy Review. 2004 Fall;5(2):77. Available from: http://www.hcs.harvard.edu/ ~hhpr/.

- Joint Learning Initiative. Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis. Cambridge (Massachusetts): Harvard University Press; 2004. p. 74.

- Carrizo J. Presentation to Charles Drew University Faculty, June 7, 2007.

- Personal communication, Dr Leonor Valdez, Vice Director of Cuban Medical Team Guatemala, August 4, 2007.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas de Guatemala, Censo 2002. Available from: http://www.ine.gob.gt/censosA.html

- Inforpress.com [homepage on the Internet]. Guatemala City, Guatemala. Servicios de Información Municipal. [updated 2007 August 1; cited 2007 August 24] Datos demograficos Coban. Available from: http://www.inforpressca.com/ coban/diagnostico_coban.pdf.

- Household incomes of $92,000 and up. Source: US Census 2000. Available from: www.census.gov.

- Cooke M, Irby DM, Sullivan W, Ludmerer KM. American medical education 100 years after the Flexner Report. NEJM. 2006 Sept 28;355 (13):1339 –44.

- Average US medical student debt is US$130,000. Source: Association of American Medical Colleges Graduate Questionnaires, 2006.

- Consejo de Educación Superior valida títulos de médicos graduados en Cuba. La Tribuna. 2007. April 20. Available from: http://www.latribuna.hn/news/45/ ARTICLE/7458/2007-04-20.html

- Médicos de la ELAM solo haran un año de servicio social, La Tribuna. 2007 May 11. Available from: http:// www.latribuna.hn/news/45/ ARTICLE/9254/2007-05-11.html.

- Pasantes de medicina de la universidad de honduras siguen de brazos caidos, La Prensa. 2007. May 5. Available from: http://www.laprensahn.com/ ediciones/2007/05/20/ pasantes_ de_medicina_de_la_universidad_de _honduras_siguen_de_brazos_caidos.

- Médicos internos y residentes aceptan volver a sus labores. La Tribuna. 2007 May 11. Available from: http:// www.latribuna.hn/news/45/ ARTICLE/9254/2007-05-11.html.

- Un día tiene MP para opinar sobre recurso del CMH. La Tribuna. 2007. August 22. Available from: http:// www.latribuna.hn/news/45/ ARTICLE/16081/2007-08-22.htm.