ABSTRACT

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is an ongoing threat to public health. Its elimination requires greater efforts to broaden antiretroviral treatment coverage, availability and personalization. HIV drug resistance is currently a global problem due to its continuing increase in recent years, undermining efficacy of antiretroviral therapy. Pretreatment HIV drug-resistance surveillance is part of WHO’s strategy for addressing antiretroviral drug resistance.

This paper describes and analyzes pretreatment HIV drug-resistance surveillance in Cuba. It presents a chronology of HIV resistance studies in untreated patients, along with their results and programmatic actions related to first- and second-line treatment regimens. Cuba’s incorporation into the Global HIV Drug Resistance Surveillance Laboratories Network and the advantages of having a WHO-designated laboratory in which to conduct periodic studies of HIV drug-resistance surveillance are described.

HIV drug-resistance surveillance in Cuba is a necessary tool in HIV/AIDS monitoring and control, as it obtains population-scale data used to inform programmatic decisions related to optimizing first- and second-line treatments for children and adults, as well as helping meet goals of eliminating HIV transmission.

KEYWORDS HIV; anti-HIV agents; drug resistance, viral; antiretroviral agents; Cuba

INTRODUCTION

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is one of the most significant advances in battling the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Since ART does not eliminate the virus in individuals, treatment must be lifelong.[1]

Many factors can affect short- or long-term ART success, including poor adherence to treatment, drug intolerance, drug interactions, individual pharmacokinetic variations and pre-existing drug resistance due to transmission of a resistant virus. Transmitted HIV drug resistance occurs when a person becomes infected with an antiretroviral (ARV) drug-resistant strain of HIV. This phenomenon may contribute to rising treatment failure rates, undermining long-term effectiveness of recommended first-line regimens.[2]

Faced with grave public health consequences associated with the emergence and transmission of HIV drug resistance, surveillance studies in untreated infected populations are crucial. An understanding of current patterns of pretreatment drug resistance can help clinicians select the most appropriate ART regimens, as well as anticipate trends that may affect optimization of resources allocated for effectively treating HIV-positive persons.[1,2]

IMPORTANCE

Pretreatment HIV drug-resistance surveillance is a vital tool in combatting the HIV/AIDS epidemic. This article describes and analyzes pretreatment HIV drug-resistance surveillance in Cuba, which has enabled identification of the most effective therapeutic combinations for achieving viral suppression and reducing transmission of resistant HIV variants; thus, Cuba expects to surpass 90% treatment adherence, proceeding towards WHO’s goal of eliminating AIDS as a health problem by 2030.

Alerted to increasing HIV drug resistance in low- and middle-income countries in recent years, WHO has issued guidelines aimed at minimizing drug resistance and contributing to achieving targets for ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030.[3]

The Global Action Plan (GAP) on HIV drug resistance, created in 2017, established requirements for providing people living with HIV (PLHIV) with more effective treatments and for preventing drug resistance from undermining efforts to meet global health goals. GAP’s strategic goals include increasing laboratory capacities for HIV drug-resistance genotyping, as well as adequate HIV drug-resistance monitoring and surveillance to obtain quality data through studies performed at regular intervals.[4]

Cuba has adopted WHO directives to confront HIV drug resistance. Monitoring and surveillance activities have been specified in several editions of the Cuban Ministry of Public Health’s (MINSAP) National Strategic Plan for Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI), HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis.[5,6] Surveillance activities include periodic studies of HIV drug resistance in patients who have not received ART, useful to MINSAP as it evaluates current and potential treatment regimens, since pretreatment resistance to ARVs in use in Cuba can affect patient results and strategies for meeting national and global goals for HIV/AIDS elimination. This paper analyzes the role surveillance of pretreatment HIV drug resistance has had as a tool for monitoring and controlling the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Cuba.

MONITORING PRE-TREATMENT HIV ANTIRETROVIRAL RESISTANCE IN CUBA

HIV drug resistance in untreated Cuban patients Since the first HIV-positive patient was diagnosed in Cuba in 1986, the national health system, through the National Program for the Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS,[5,6] has designed strategies for the prevention, diagnosis, treatment and epidemiological surveillance of the disease.

Several studies have focused on determining which genetic variants of the virus are circulating in the seropositive Cuban population, given their implications for diagnosis, transmissibility and clinical progression.[7–9]

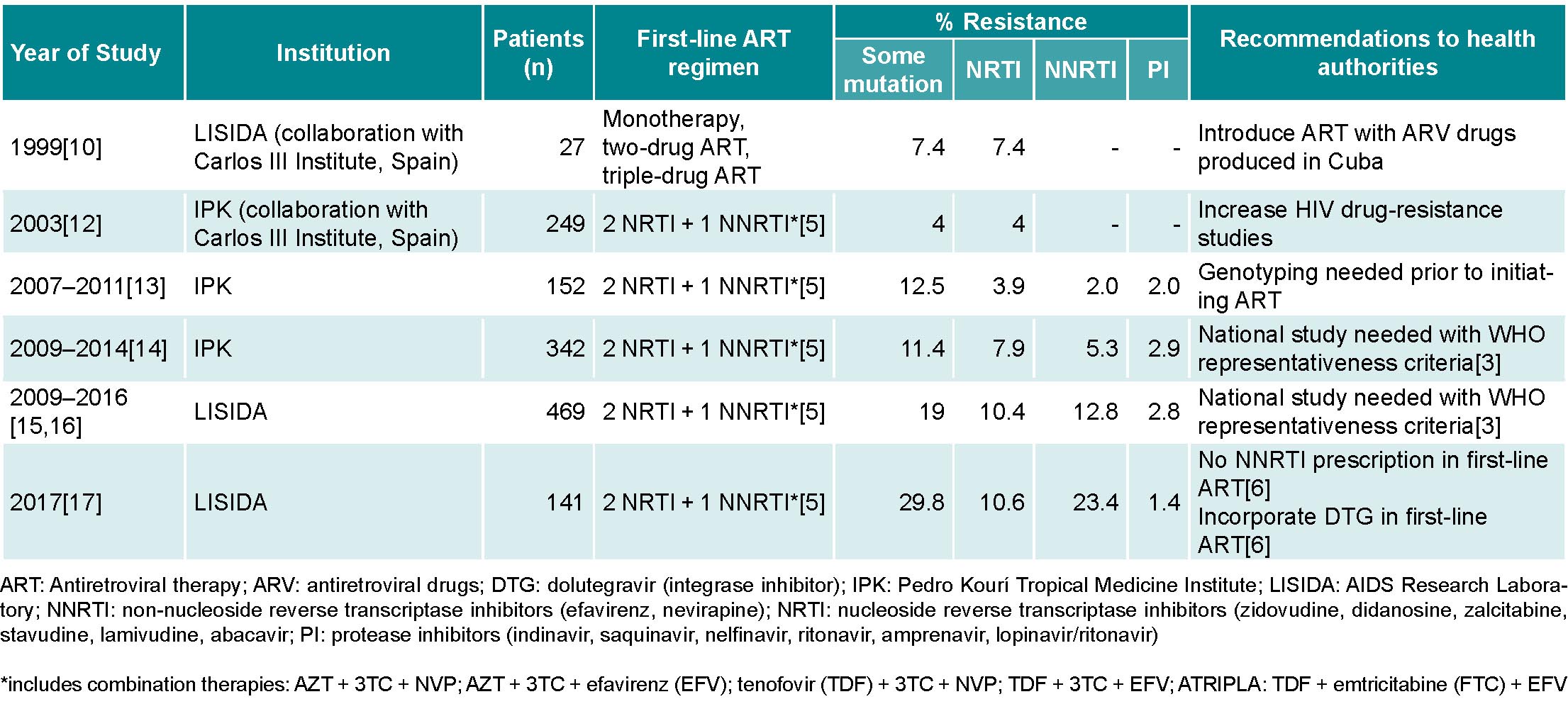

Before ART was initiated in Cuba, a group of Cuban researchers, in collaboration with the Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII) in Spain, conducted a pilot study to determine HIV drug-resistance prevalence in seropositive patients treated with monotherapeutic or two-drug ARV regimens, as well as in patients not receiving ARV. The results showed a low prevalence of mutations that generate resistance to reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTI) and protease inhibitors (PI),[10] which aided in selecting ARVs that would later be produced by Cuba’s domestic biopharmaceutical industry: zidovudine (AZT), nevirapine (NVP), lamivudine (3TC), stavudine (d4T), indinavir (IDV) and didadosine (DDI) (Table 1).[11]

The introduction of ART in Cuba in 2001 (with domestically-produced generic ARVs) helped reduce the incidence of opportunistic infections and mortality from HIV/AIDS, as well as improve quality of life in PLHIV.[11] By the end of 2018, more than 90% of all PLHIV who initiated treatment in 2007 remained alive.[5,6] However, prolonged ART use in the seropositive population is known to foster emergence of HIV drug-resistant genetic variants in these patients and therefore potential transmission of the resistant strains to the untreated HIV-positive population.[18]

Two years after the introduction of domestically-produced generic ARVs, another group of Cuban researchers in collaboration with the ISCIII in Spain evaluated HIV drug resistance in seropositive Cuban patients. That study included 249 untreated patients and detected a low prevalence (4%) of mutations associated with HIV drug resistance.[12] During 2007–2011 and 2009–2014, researchers at the Pedro Kourí Tropical Medicine Institute (IPK) in Havana studied changes in drug resistance in 152 treated and 342 untreated patients (samples obtained immediately prior to beginning treatment), and results showed moderate resistance prevalence (12.5% and 11.4%, respectively) (Table 1).[13,14]

Although several factors interfere with the goal of achieving total ART coverage, Cuba has experienced a sustained increase, reaching approximately 83% of PLHIV.[6] In order to support this goal, and with financial assistance from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, HIV drug-resistance genotyping was introduced in 2009.

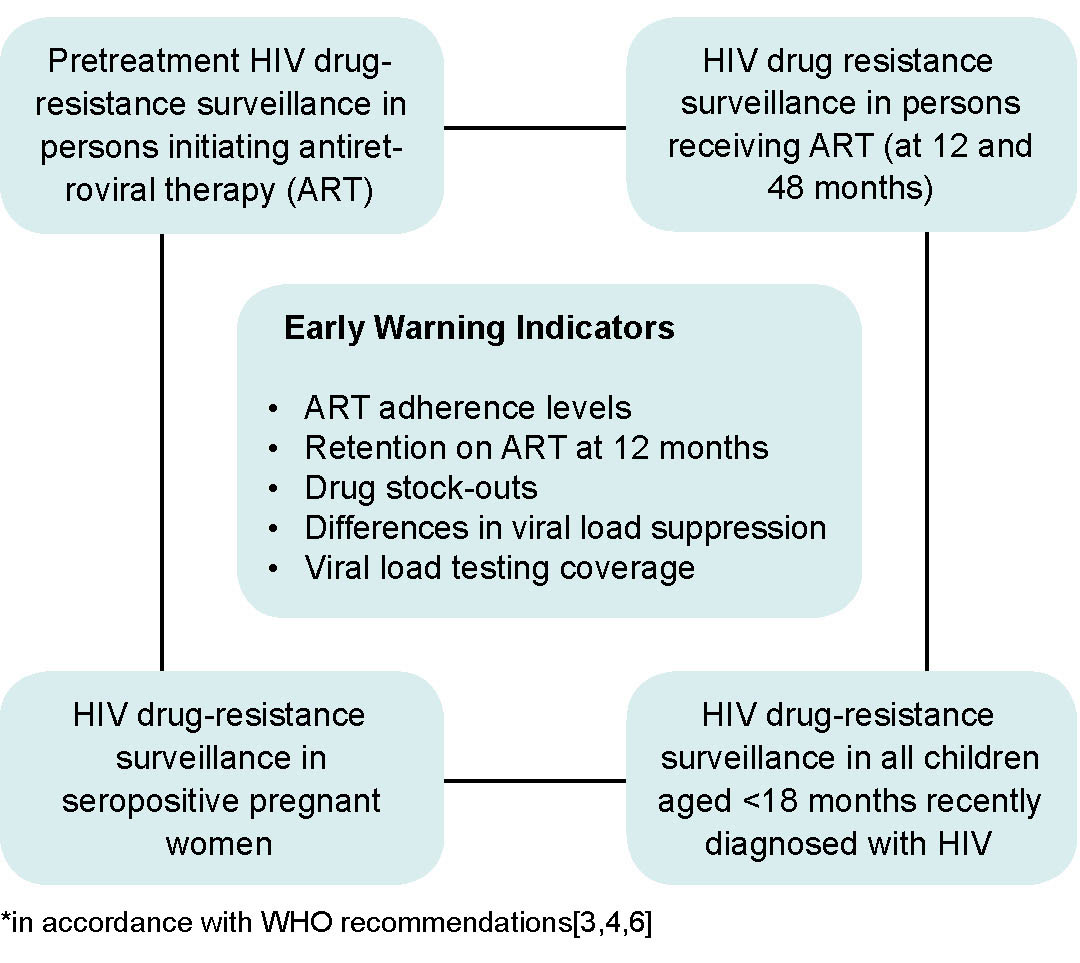

WHO recommends that countries with ART programs establish sentinel surveillance systems to detect HIV drug resistance and make evidence-based recommendations for preventing drug resistance. Such surveillance is aimed at minimizing the emergence of drug resistance, prolonging the efficacy of first- and second-line therapies, and selecting adequate therapeutic regimens for pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis (Figure 1).[3] In response to those recommendations, MINSAP decided that IPK and the AIDS Research Laboratory (LISIDA) would be in charge of HIV drug-resistance genotyping. Since then, surveillance of HIV drug resistance in a sample of patients with no prior treatment history was undertaken by LISIDA.[5,6]

Once infrastructure was created and staff trained, LISIDA initiated studies of HIV drug resistance in untreated individuals in June 2009. From that date until December 2016, with the permanent collaboration of primary healthcare teams at community polyclinics who were providing care to PLHIV in each province, 469 patients recently diagnosed with HIV infection who had not yet initiated ART were studied. Of those patients, 19% (89) presented a virus with some mutation associated with pretreatment HIV drug resistance: 10.4% (48) to nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), 12.8% (60) to non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) and 2.8% (13) to protease inhibitors. The most frequent mutations were K103N/S and Y181C in the NNRTI family, which reduced susceptibility to drugs like NVP and efavirenz (EFV). In the NRTI family, the most frequent mutations were M184V/I (resistance to 3TC) and D67N (resistance to AZT).[15,16] The results showed a high prevalence of pretreatment HIV drug resistance and, consequently, the need to change first- and second-line therapeutic regimens used by the National Program for the Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS. However, studies conducted in 2009–2016 did not take into account WHO recommendations for sampling and selection of individuals for surveillance of pretreatment drug resistance (Table 1).

In December 2016, LISIDA specialists, in collaboration with the MINSAP’s STI, HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis Program and PAHO, designed a national survey of HIV drug resistance in pretreatment patients, following WHO recommendations,[3] aimed at estimating pretreatment HIV drug-resistance prevalence in the seropositive Cuban population.