Individually, genodermatoses are rare, but together they comprise a large group that is difficult to diagnose, treat and monitor due to their diversity in presentation and inheritance, even within the same disease.[4] Neurofibromatosis, Leopard syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and tuberous sclerosis are diagnosed via clinical exam,[5,6] while ichthyosis, Darier disease, epidermolysis bullosa and mastocytosis are confirmed through histopathology.[5] In other cases, such as xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), supplemental studies are not conclusive. To diagnose the aforementioned conditions, Cuba uses histopathology, which is not conclusive, and single gel electrophoresis (SCGE) on isolated lymphocytes from peripheral blood to evaluate DNA’s ability to repair itself after damage is induced by ultraviolet light, a test which is not 100% specific to XP.[7] In general, there are no genetic tests available for mass screening of these conditions.

Genodermatosis lesions can be very visible and have a psychological impact on patients, and can result in social stigma, negatively impacting their quality of life. Many genodermatoses lead to chronic disability, others to death.[4]

It is difficult to gather precise data on the prevalence of genodermatoses (especially in developing countries), due to the diversity of diseases that are grouped under this common name, many of which go undiagnosed. In the most studied diseases, the results vary from one country to the next. Worldwide, the incidence of hypomelanosis of Ito is 1 per 7540–10,000 live births;[8] ectodermal dysplasia, 1 per 100,000 births;[9] oculocutaneous albinism, 1 per 18,000 births;[10] incontinentia pigmenti, 1 per 40,000–50,000 births;[11] tuberous sclerosis, 1–5 per 10,000 live births;[12] epidermolysis bullosa, 1 per 500,000 live births;[13] and Waardenburg syndrome, 1 per 42,000 births.[14]

Few population studies on genodermatoses have been conducted in Cuba. Dorticós conducted research to characterize them in a study involving 10 hospitals in Havana from 1980 to 1986, in which ichthyosis (37.7%) and neurofibromatosis (18.8%) were the most common genodermatoses.[15] Campo Díaz published a study on Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type III conducted in Pinar del Río Province in 2010–2011, finding 100% with manifestations on the skin and 59.3% with associated bleeding disorders.[16] Orraca also made a genetic, clinical and epidemiological characterization of neurofibromatosis type 1 in Pinar del Río Province, finding a prevalence of 1 per 1141 in pediatric patients, above rates reported globally for this disease.[17] One study performed in 2015 in Las Tunas, an eastern Cuban province, suggested that 85% of genetic diseases treated at the Provincial Medical Genetics Department (PMGD) were diagnosed in pediatric patients; of those, 22% were dermatological.[18]

WHO estimates that there are approximately 10,000 genetic diseases affecting 7% of the world population.[19] Genetic diseases make up 25% of pediatric hospital admissions, with 15% of cases affecting the skin and adnexa.[20]

Since 1963, WHO has urged member states to focus on the control and prevention of genetic diseases (through early diagnosis, access to care, genetic counseling, etc.).[21] In developed countries, there are numerous foundations dedicated to the treatment of specific genetic diseases, but there is no unifying vision that involves all levels of health care. In 1980, Cuba’s national health system implemented the National Program for the Diagnosis, Care, and Prevention of Genetic Diseases and Congenital Abnormalities,[22] which we will identify below as NGP (National Genetics Program). This program is supported by a network of Genetics Counseling Service comprising 172 Medical Genetics Municipal Departments (in every municipality in the country), 16 PMGD (located in all Cuban provinces), and the National Medical Genetics Center (CNGM), a lead institution that provides coverage to the entire population. CNGM is a collaborative center focused on genetic developments that help promote health worldwide.[22]

NGP’s work is guided by the Manual of Regulations and Procedures for medical genetics services in Cuba,[23] which offers standards for mass screening for some genetic diseases via specialized screening. NGP not only offers specialized medical care, but also conducts preventive prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal services (at the three levels of prevention: primary, secondary, and tertiary) for early detection of congenital diseases and abnormalities; supports research aimed at designing education strategies for patients, their families, and the general public; and works to promote social inclusion of affected persons and improve their quality of life.[22] Masters and specialists in clinical genetics regularly conduct exchanges for diagnostics and patient follow-up with those in other fields (gynecology and obstetrics, ophthalmology, endocrinology, orthopedics, otorhinolaryngology, neonatology, immunology, molecular biology, dermatology, pediatrics, psychology, neurology, cardiology, oral medicine, pathology and imaging, etc.).[23]

NGP was established in Las Tunas Province in 1989. In 2010, a specialized multidisciplinary provincial service was established to care for genodermatosis patients. This bi-weekly service is managed by specialists in clinical medical genetics and dermatology, the service’s main specialties, with support from psychologists, immunologists, pediatricians and others, depending on patient characteristics and symptoms. From 2010 to 2012, the most common genodermatoses were ichthyosis (16.7%), mastocytosis (11.7%), and neurofibromatosis (8.3%). The most affected were patients <12 years of age (61.6%).[24]

The objective of this study was to describe genodermatoses in Las Tunas Province, Cuba, since the establishment of NGP, and after the creation of a specialized multidisciplinary provincial service for genodermatosis patients.

METHODS

Study type and participants A descriptive observational study was performed, with cross-sectional and retrospective components. It was conducted at the PMGD’s specialized multidisciplinary provincial genodermatoses service in Las Tunas Province, Cuba, and comprised the years 1989–2019. The universe was composed of 942 patients with genetic disease diagnoses, registered in the PMGD database and, for non-probability sampling, 249 patients who met the diagnostic criteria of genodermatoses.

Inclusion criteria Patients seen at the service, who met genodermatosis diagnostic criteria, and who gave written informed consent to participate in the study (in the case of minors, parents or guardians authorized patient participation).

Exclusion criteria Patients seen at the clinic, but whose medical records did not contain all data necessary for the study, or who had psychiatric conditions that would prevent necessary data collection.

Diagnostic criteria Genodermatoses are considered clinical conditions whose primary phenotypic manifestations involve the skin and adnexa and that have a genetic component. Patient genealogy was examined to determine genetic history, inheritance patterns and the diagnosis of new cases in the family since the proband case.[23] In all cases the diagnosis was confirmed by a clinical geneticist.

Supplemental studies were performed to corroborate the diagnosis or presence of complications. These studies were: hematological (liver transaminases, eosinophil count, peripheral blood smears to explore the presence of mast cells in peripheral blood);[25] histopathological (skin biopsy for microscopic diagnosis of aplasia cutis, cutis laxa, cutis verticis gyrata, congenital ectodermal dysplasia, Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, epidermolysis bullosa, hypomelanosis of Ito, ichthyosis, incontenencia pigmenti, mastocytosis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, porokeratosis of Mibelli, palmoplantar keratoderma, Netherton syndrome, Proteus syndrome, and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome);[1,2] imaging (ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging; fundamental in diagnosing neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis and Sturge-Weber syndrome);[23] genetic, to corroborate genodermatosis diagnoses whose clinical presentations were not conclusive on their own or to differentiate them from other clinically similar conditions, such as SGCE on isolated lymphocytes XP diagnosis;[7] indirectly using five markers: four microsatellite markers (IVS27AAAT2.1, IVS38GT53.0, IV27AC28.4 and Mfd15) and one restriction fragment length polymorphism (Rsa I NF1 exon 5) to diagnose neurofibromatosis type 1;[17] and other studies required to diagnose infectious complications, such as bacterial and fungal cultures.[2]

The foundation of all diagnoses in the study were initial clinical exam and personalized physician–patient relationships, the fundamental pillars of diagnostics in general, especially when advanced technology is not available to corroborate the suspected clinical condition.[26]

Variables

Diagnosed genodermatoses (based on diagnostic criteria) The following were considered: Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) [OMIM 203100 203200 203290 606574 615312 113750 615179 606952 ORPHA 55 GARD 10958], aplasia cutis [OMIM 107600 600360 ORPHA 1114 GARD 5835], cutis laxa [OMIM 123700 6144434 616603 219100 ORPHA 90348 90349 GARD 1639 8480], cutis verticis gyrata (CvsG) [OMIM 123790 ORPHA 671 GARD 1643], autosomal dominant hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED-AD) [OMIM 129490 224900 614940 617337 ORPHA 238468 GARD 76], Darier disease (Darier) [OMIM 124200 ORPHA 218 GARD 6243], Hailey-Hailey disease (Hailey-H) [OMIM 169600 ORPHA 2841 GARD 6559], Niemann-Pick disease (Nieman P) [OMIM 257200 607616 257220 607625 ORPHA 77292 77293 646 GARD 7206 10729], generalized epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EB simplex) [OMIM 131900 ORPHA 79399 GARD 2147], junctional epidermolysis bullosa, Herlitz type (EB Herlitz) [OMIM 226700 ORPHANET 79404 GARD 2153], tuberous sclerosis (TS) [OMIM 191100 613254 ORPHA 805 GARD 7830 946], hypomelanosis of Ito (H. Ito) [OMIM 300337], ichthyosis vulgaris (Ichthyosis V) [OMIM 146700] Lamellar ichthyosis (Ichthyosis L) [OMIM 615024 ORPHA 313], incontinencia pigmenti (I.Pigmenti) [OMIM 161000 ORPHA 69087 GARD 3912], cutaneous mastocytosis [OMIM 154800 ORPHA 66646 GARD 7842], neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) [OMIM 162200 ORPHANET 636 GARD 7866], segmental neurofibromatosis (Segmental NF) [OMIM 162200], piebaldism [OMIM 172800 ORPHA 2884 GARD 4344], pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) [OMIM 173200 ORPHA 2897 GARD 7401], classic porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM) [OMIM 175800 ORPHA 735 GARD 4438], epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) [OMIM 144200 600962 ORPHA 2199 496 GARD 2826 5186], Albright syndrome (S. Albright) [OMIM 174800 ORPHA 562 GARD 6995], occipital horn syndrome (OH) [OMIM 304150 ORPHA 198 GARD 4017], classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (ED) [OMIM 130000 130010 ORPHA 98249 GARD 6322], LEOPARD syndrome (LEOPARD) [OMIM 151100 611554 613707 ORPHA 500 GARD 1100], Netherton syndrome (Netherton) [OMIM 256500 ORPHANET 634 GARD 7182], Noonan syndrome (Noonan) [OMIM 163950 605275 609942 610733 611553 613224 613706 615355 616559 616564 618499 618624 ORPHA 648 GARD 10955], Proteus syndrome (Proteus) [OMIM 176920 ORPHA 744 GARD 7475], Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (R-T) [OMIM 618625 ORPHANET 2909 GARD 4392], Sturge-Weber syndrome (S-W) [OMIM 185300 ORPHA 3205 GARD 7706], Waardenburg syndrome type I (W-I) [OMIM 193500 ORPHA 3440 GARD 5525] and xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) [OMIM 278700 278720 278730 278740 278760 278780 610651 ORPHA 910 GARD 7910].

New cases New cases diagnosed per year, for each genodermatosis.

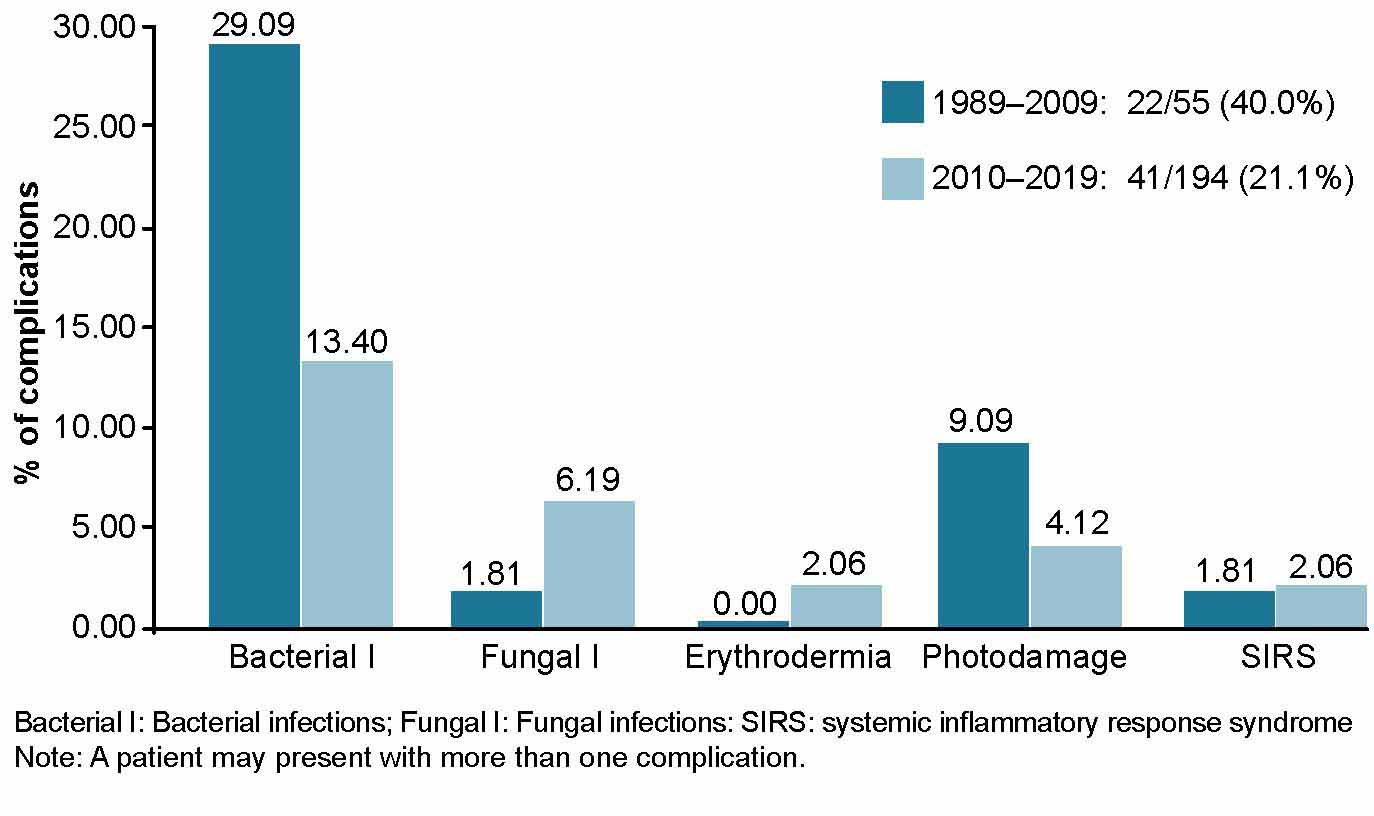

Complications We considered complications secondary to skin abnormalities due to genodermatosis, such as secondary pyoderma (Bacterial I),[2] superficial cutaneous mycoses (Fungal I) and within these, dermatophytosis and mucocutaneous candidiasis, erythroderma, sun damage (sun burns, sun freckles, elastosis, premalignant lesions, skin cancer) and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). The number of patients with each complication were considered.

Number of deaths and diagnosis Deceased patients with genodermatosis and genodermatosis diagnosis at death.

Geographic location by municipality All municipalities of the province were considered: Amancio Rodríguez, Colombia, Jesús Menéndez, Jobabo, Las Tunas, Majibacoa, Manatí, and Puerto Padre. This variable provides important epidemiological elements pertaining to inheritance patterns, potential consanguinity and prevalence of specific genodermatoses within particular regions.

Data collection and analysis Information was collected using primary sources consisting of patients of legal age and parents or guardians of patients who were minors, and secondary sources consisting of the patient’s medical record and records from PMGD and specialized multidisciplinary provincial clinic for patients with genodermatoses. Techniques used to obtain information included participatory structured observation, face-to-face medical interviews, and general and more targeted physical examinations, as well as a review of secondary sources. All information was gathered in a Microsoft Excel database and was processed using the SPSS Version 18 for Windows.

Prevalence rates were calculated per 100,000 population, taking into consideration the population of Las Tunas Province in 2019 (535,335 inhabitants), according to the Cuban National Statistics and Information Bureau (ONEI).[27]

The annual incidence rate of genodermatosis was calculated for 2010–2019 (the period following the implementation of the specialized multidisciplinary provincial service for patients with genodermatoses), as was the proportion of complications. Two periods of time were compared, from the start of the National Genetics Program in 1989 to implementation of the specialized multidisciplinary provincial clinic for patients with genodermatoses in 2009, and during the clinic’s operation in 2010–2019. We also calculated the survival index (100 x number of survivors annually/total patients), fatality rate (100 x number of deaths per year/total patients), and number of genodermatoses diagnosed per municipality (number of patients/municipality population) x 100) for each genodermatosis.

To compare results among municipalities, the population of each was taken into consideration (according to ONEI data): 37,695 inhabitants in Amancio; 32,167 in Colombia; 48,208 in Jesús Menéndez; 42,603 in Jobabo; 211,596 in the municipality of Las Tunas; 41,287 in Majibacoa; 29,930 in Manatí, and 91,879 in Puerto Padre.[27]

Ethical considerations The research protocol was approved by the research ethics committee and scientific council at Mártires de las Tunas Provincial Pediatric Hospital and research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.[28] To participate in the study, written informed consent was obtained from patients (or parents or guardians of patients who were minors). The written information provided explained the importance of participation, the risks and benefits, participants’ rights and study characteristics. Data was coded to protect patient identity.

RESULTS

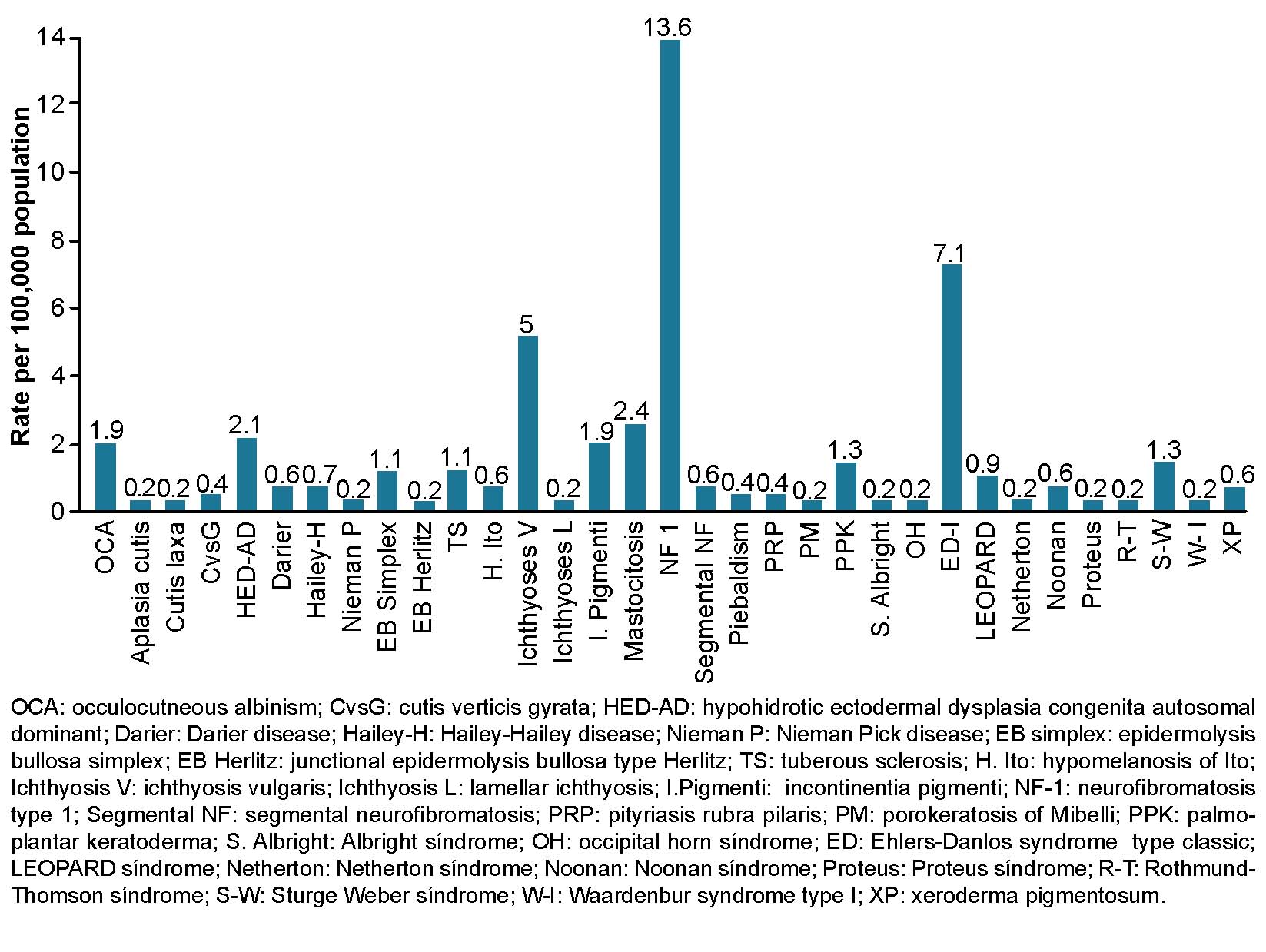

From 1989 through 2019, general prevalence rate of genodermatoses in Las Tunas Province was 46.5 per 100,000 population. Neurofibromatosis type 1 was predominant at 13.6 cases per 100,000 population, followed by classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome at 7.1 per 100,000, ichthyosis vulgaris at 5 per 100,000 and cutaneous mastocytosis at 2.4 per 100,000 (Figure 1).

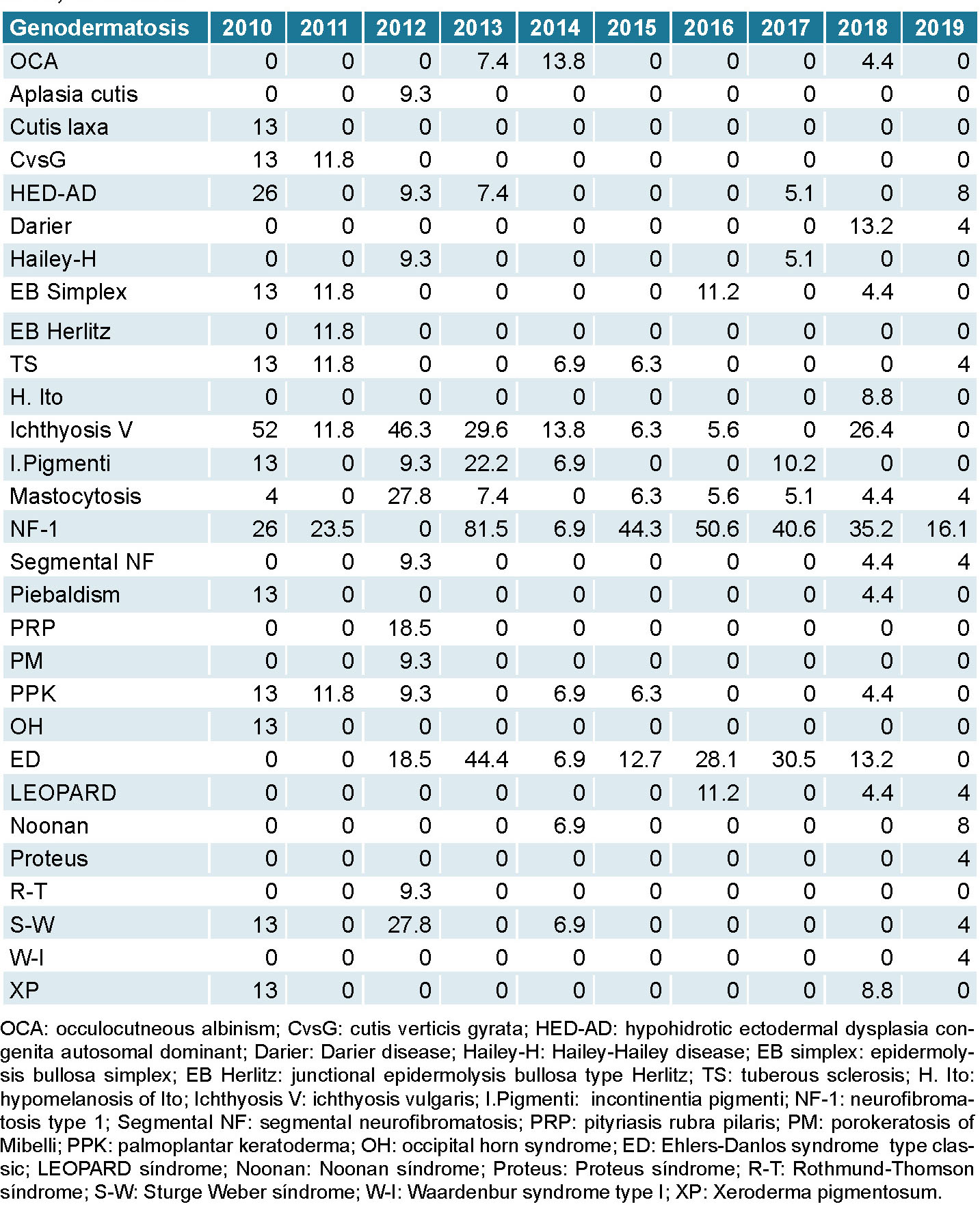

From 2010 through 2019 highest recorded incidence rates were for neurofibromatosis type 1 at 81.5 per 1000 (2013), 50.6 per 1000 (2016), and 40.6 per 1000 (2017). The next highest rates were for ichthyosis vulgaris at 52 per 1000 (2010) and classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome at 44.4 per 1000 (2013). During this time, all rates decreased and the lowest were observed in 2019, the last year of the study (Table 1).