INTRODUCTION

Vaccines have been developed to prevent disease and are generally administered to healthy people, primarily children. They have had a major impact on controlling infectious diseases, but as these become less frequent, adverse events that can appear following vaccine administration have acquired greater importance, raising doubts about immunization in the public mind.[1]

Vaccination programs are acknowledged as having prevented more infectious diseases and deaths worldwide than any other intervention in the history of public health.[2] Among public health measures, vaccination has the second most favorable cost-benefit ratio after provision of safe drinking water, contributing to increased life expectancy and time devoted to productive activities, and hence to poverty reduction.[2,3]

Nevertheless, vaccination is not without controversy. News about a 1999 British study linking the measles–mumps–rubella combination vaccine with autism[4] was widely circulated and many parents stopped having their children vaccinated. The unfortunate result was the emergence of measles cases and related deaths ten years later. Other countries such as Austria, Israel, Italy, Switzerland and the United States, also experienced measles outbreaks. Several studies found no evidence that the vaccine caused autism, but there was tangible evidence of new cases of measles and of measles-related deaths because of falling vaccination rates.[5,6]

Hence, sustained vaccination program effectiveness depends on continued public confidence. Like any drug or medical technology, vaccines are subject to rigorous testing to evaluate their safety, immunogenicity and efficacy before being licensed for human use, but the need for vigilance does not stop there. Once on the market, vaccines must be monitored to detect any rare or unexpected adverse events not observed in premarketing clinical trials.[7,8]

When WHO created the Expanded Program on Immunization in 1974, it recommended that its member countries set up postmarketing surveillance systems for adverse events following vaccination to enhance health systems’ ability to ensure vaccine safety and to maintain public confidence in and acceptance of vaccination programs.[9] Such systems monitor suspected vaccine-associated adverse events (VAAE) [8,10] and assess both their severity and likely relationship to the vaccine or to the circumstances of its administration.[8,11,12]

Common minor events such as local reaction, fever and malaise are part of the normal immune response and can also be caused by vaccine components, such as aluminum hydroxide or preservatives.[8,12] Virtually all rare and severe events (e.g., seizures, thrombocytopenia, hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes, persistent crying) leave no aftereffects or sequelae. Although anaphylaxis can be fatal, it leaves no sequelae if treated in a timely manner. Encephalopathy is cited as a rare reaction to the measles and the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis or whooping cough (DTP) vaccines, but a causal relationship has not been demonstrated.[8,12,13]

It is hard to determine whether a VAAE is actually the result of vaccination or simply coincides with it; most vaccines are administered in the first years of life, precisely when problems such as hearing loss and developmental disorders become noticeable. If a causal relationship does exist, it is furthermore necessary to distinguish between the effect of the vaccine itself and program errors in vaccine transport, storage, handling, or administration.[14]

In 1962 Cuba created the National Immunization Program (NIP), grounded in four basic principles: accessibility, provision of vaccines at no cost to the patient, universality and active community participation.[15] The NIP vaccination schedule includes 11 vaccines—70% of which are now domestically produced—protecting against 13 diseases (Table 1).[16] Vaccine-preventable diseases have become less of an issue in Cuba thanks to NIP’s effectiveness: with >95% coverage,[17] it has brought about the elimination of five diseases (polio, diphtheria, measles, pertussis, and rubella), two severe clinical forms (neonatal tetanus and tuberculosis meningitis), and two serious complications (congenital rubella syndrome and mumps meningoencephalitis). Other diseases—such as tetanus, typhoid fever, mumps and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infections—are no longer public health problems. Morbidity and mortality from meningococcal disease and hepatitis B have plummetted, falling by more than 95% since 2002 and 2003, respectively.[17]

Table 1: Current pediatric vaccination schedule in Cuba

AM–BC: meningococcus B and C

BCG: serious forms of tuberculosis

DT: diphtheria and tetanus

DTwP: triple bacterial vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis

DTwP+HB+Hib: pentavalent vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b

HB: hepatitis B

Hib: Haemophilus influenzae type b

MMR: measles, mumps, and rubella

OPV: oral polio vaccine

TA: typhoid fever

TT: tetanus toxoid

Adapted from: Reed and Galindo[16]

Hence, the greater attention to VAAEs and establishment in 1999 of a surveillance system for their detection.[18] Cuba’s National Drug Regulatory Authority (CECMED—its Spanish acronym) sets policy for research methodology, as well as roles and responsibilities in VAAE detection.[19] Thus, CECMED collaborates closely with the NIP’s VAAE surveillance system,[9,19] which carries out the basic functions established by WHO of compiling and evaluating information on vaccine quality, efficacy, and safety once they are in use.[19]

The VAAE surveillance system operates at all levels of the health system and includes not only reporting but educating health personnel and training heads of all immunization programs in the provinces and municipalities, including nurses and family physicians. The system is passive, in that it depends on health personnel—primarily the family physician—taking the initiative to report a VAAE by filling out an epidemiological questionnaire[19] and sending it to the polyclinic to which he/she reports, whence it proceeds to the municipal, provincial and national levels.

When reporting a severe adverse event, the family physician is required to immediately call the Deputy Director of Hygiene and Epidemiology at the polyclinic to which he/she reports, triggering an epidemiologic investigation, conducted by the polyclinic health area’s epidemiologist and the head of the municipal and provincial immunization program to confirm or rule out the possibility that the event is related to vaccine administration.[18] When there is a need for heightened surveillance of new vaccines in the immunization schedule, the head of NIP issues countrywide instructions for active surveillance. The Pedro Kourí Tropical Medicine Instititute (IPK, its Spanish acronym) processes data received to meet established program objectives. The director of VAAE surveillance at IPK and the head of NIP in the Ministry of Public Health are jointly responsible for quality assurance, data analysis and VAAE surveillance system performance.[18]

The objective of this study was to describe the type, extent and impact of reported VAAEs in children in Cuba between 1999 and 2008.

METHODS

A retrospective descriptive study was conducted of VAAEs reported in Cuba from January 1, 1999 through December 31, 2008 in children aged ≤16 years.

Study variables The definition of VAAE used is that established by PAHO for use by member states with VAAE surveillance systems: clinical symptoms following the administration of a vaccine that might be related to it and that arouse concern in the population.[12] Variables examined included demographics, vaccine type, events reported and event classification by cause (Table 2).

Table 2: Study variables

VAAE investigation A national multidisciplinary expert commission, including both physicians and nurses, investigates all cases of reported severe VAAEs to confirm or rule out causality and determine other possible causes of any event severe enough to cause death or residual disability.[18] The commission reviews data on patient demographics, vaccine(s) administered, and program operations, to determine probable cause as follows:

- VAAE related to vaccination:

- Caused by the vaccine itself, when the VAAE is closely related to components of the vaccine, to which the vaccinated person may be allergic.

- Program error, when vaccines are administered at the wrong site or via the wrong route; when needles and syringes are unsterilized or are handled improperly; when vaccines are reconstituted with inappropriate dilutants; when the recommended dose is exceeded; when vaccines or dilutants are contaminated; when other products are substituted for vaccines; or when vaccines are stored improperly.

- VAAE unrelated to vaccination or coincidental, when it is demonstrated that the event could have occurred even if the individual had not been vaccinated.

- Inconclusive VAAE, when the commission is unable to conclude that the event is coincidental and cannot rule out causation by vaccine or program error.[19,20]

Data collection and analysis The primary source of information was the epidemiological reporting questionnaire.[21] All questionnaires received from all Cuban provinces during the study period were reviewed. Data were entered in an Excel database for calculations of absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) and of overall and specific rates (by age, sex, province of residence, vaccine). The adverse event rate was calculated per 100,000 doses administered (DA) by year. Data were organized in tables and figures for analysis.

RESULTS

In the ten years following implementation of the surveillance system, 45,237,532 doses of vaccine were administered. A total of 26,159 VAAEs were reported using the epidemiological questionnaire, yielding an overall rate of 57.8/100,000 DA. In 1999, 2004, 2005, and 2008, values above the overall rate for the decade were reported. The highest rates were reported in the first and last years of the study period, 1999 and 2008, (76 and 75/100,000 DA, respectively). The lowest rate was reported in 2003 (39.7/100,000 DA).

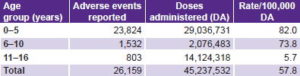

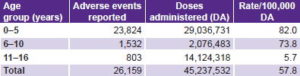

No substantial differences were found in the reporting of VAAEs by sex. A total of 12,621 events were reported in male (48.2%) and 13,538 female children (51.8%). The group aged 0–5 years had the highest VAAE rate (82/100,000 DA), while the group aged 11–16 years had the lowest (5.7/100,000 DA) (Table 3).

Table 3: Incidence of adverse events following vaccination by age group in Cuba, 1999–2008

Source: Adverse events surveillance system, IPK

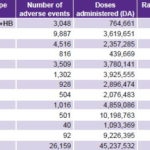

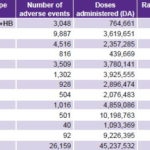

The DTwP vaccine and combinations thereof had the highest rate of reported adverse events; oral polio vaccine (OPV) had the lowest (Table 4).

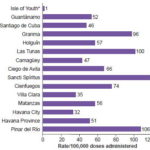

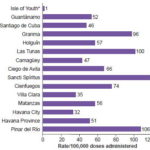

All 14 provinces and the Isle of Youth Special Municipality reported VAAEs. Sancti Spíritus (115/100,000 DA), Pinar del Río (106/100,000 DA), and Las Tunas (100/100,000 DA) had the highest rates. The provinces of Havana City (32/100,000 DA), Villa Clara (35/100,000 DA), and the Isle of Youth Special Municipality (1/100,000 DA) had the lowest rates (Figure 1).

The vast majority of VAAEs reported were common minor effects (percentages add to >100.0 because one VAAE could involve multiple symptoms): fever, 17,538 (67.0%); local reactions at injection site, 4470 (17.1%); systemic side effects, 2422 (9.3%). Rare events reported included persistent crying, 2666 (10.2%); febrile seizures, 112 (0.4%); hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes, 3 (0.01%); and encephalopathy, 2 (0.008%).

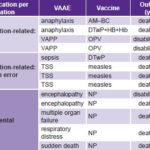

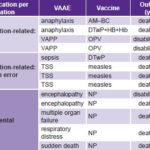

There were 13 events severe enough to cause death or disability and trigger an investigation into causation. These included two cases of anaphylaxis (0.007%); one each of respiratory distress, multiple organ failure and sudden death (0.004%); two of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) (0.007%), three of toxic shock syndrome (0.01%); and one of sepsis (0.004%) (Table 5).

Table 4: Adverse events reported by vaccine type in Cuba, 1999–2008

AM–BC: meningococcus B and C

BCG: Bacillus Calmette Guerin (serious forms of tuberculosis)

DT: diphtheria and tetanus

DTwP: triple bacterial vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis

DTwP+HB+Hib: pentavalent vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type b

HB: hepatitis B

Hib: Haemophilus influenzae type b

MMR: measles, mumps, rubella

OPV: oral poliomyelitis vaccine

TA: typhoid fever

TT: tetanus toxoid

Source: Adverse events surveillance system, IPK

Figure 1: Provincial* variation in vaccine-related adverse event rates in Cuba, 1999–2008

*includes Isle of Youth Special Municipality / Source: Adverse events surveillance system, IPK

The expert commission’s investigation of the 13 severe VAAEs concluded that eight of these were vaccination‑related, four of them related to program error and four to the vaccine: two cases of VAPP caused by OPV, both left with disabilities; and two cases of anaphylaxis. Both cases of anaphylaxis and all four VAAEs due to program error were fatal. The other five VAAEs were considered coincidental and unrelated to vaccination (respiratory distress, multiple organ failure, sudden death, and the two cases of encephalopathy). There were four deaths among the coincidental VAAEs and one patient was left with encephalopathy-related disability, for a total of ten deaths (0.022/100,000 DA) and three cases of disability (0.007/100,000 DA) among all VAAEs (Table 5).

Table: 5: Severe vaccination-associated adverse events in Cuban children, 1999–2008

AM–BC: meningitis B and C vaccine

DTwP: diphtheria, tetanus and whole-cell pertussis vaccine

DTwP+HB+Hib: pentavalent vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b

NP: not published (because VAAE ruled coincidental)

OPV: Oral poliomyelitis vaccine

TSS: Toxic shock syndrome

VAAE: Vaccine-associated adverse event

VAPP: Vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis

Source: Adverse events surveillance system, IPK

Among the four cases classified as program errors, three occurred in 2002 during the measles mop-up campaign conducted in Cuba every nine years to increase vaccination coverage. It was found that the three cases of toxic shock syndrome followed administration of an imported measles vaccine containing an unsterile dilutant. The fourth, a sepsis case reported in 2004, was due to lack of compliance with vaccine administration standards.

DISCUSSION

Differences in reporting systems make comparisons between countries, and hence, with this study, difficult. Cuba’s adverse events surveillance system routinely reports overall rates per 100,000 DA by year, type of vaccine, and province. The structure of Cuba’s health system, with the entire population enrolled at the primary care level for continuous assessment and risk evaluation,[22] facilitates collection and analysis of comprehensive and reliable data at the primary care level. This enables reporting on VAAEs per dose administered, not just per dose distributed, as in some systems. For example, the VAAE surveillance system in the United States (VAERS) provides the number of adverse events reported among doses distributed.[23] In the period 1991–2001, there were 128,717 VAAE for 1.9 billion doses distributed; the overall reporting rate for the 27 most common vaccines was 11.4 reports/100,000 doses distributed.[23] The rate per dose distributed is obviously lower than the rate per DA. A three-year study in Brazil did report doses adminstered, but not by year, simply the cumulative overall rate per DA for each type of vaccine (with BCG exhibiting the highest rate per DA during the study period and the DTP vaccine the second highest).[24]

The highest VAAE rates in the study period were seen in the first and last years of the series. The years 2004, 2005, and 2008 had adverse event rates that were higher than the overall rate for the period; this was likely related to changes in the immunization schedule connected with the introduction of Cuban vaccines such as Hib in 2004, the tetravalent vaccine (DTwP–HB) in 2005, and the pentavalent vaccine (DTwP–HB–Hib) in 2006, which were subject to stricter surveillance (unpublished information, NIP). The rate in 2003 was lower than in the other years, which may have been influenced by the reorganization of primary care at the time, involving a decrease in total number of family physicians.

The highest VAAE rate reported was in the group aged 0–5 years. This was expected, since Cuba’s vaccination schedule includes a large number of vaccines for this age group.[16] The literature contains reports of different studies on adverse events by age group, but they are not comparable because they do not match the age groups in our study.[23]

The DTwP vaccine exhibited the highest adverse event rates during these years. Despite its acknowledged efficacy, it is known to be associated with a significant number of adverse effects.[24] The causative agent of whooping cough is Bordetella pertussis. The whole-cell Bordetella pertussis component is largely (but not exclusively) responsible for reactions following admininistration of DTwP and its combinations with other components (such as HB and Hib).[25,26] Eliminating it from the NIP is not advisable, however. The experience in Japan reported in 1975 showed that a 20% reduction in DTwP vaccination coverage led to a pertussis epidemic that resulted in high morbidity and mortality.[27] A similar phenomenon occurred in the United Kingdom and Sweden.[28,29] The DTaP (acellular) vaccine currently available on the market is less reactogenic, but its high price puts it out of reach for developing countries, so it is currently infeasible to add to Cuba’s vaccination schedule.

VAAE reports submitted by Cuba’s 14 provinces and the Isle of Youth Special Municipality demonstrate the national scope of the VAAE surveillance system. However, VAAE rates reported vary widely by province. Other monitoring and analytic studies are needed to understand this provincial variability.

Predominance of fever and local reactions at the injection site among VAAEs seen here coincide with reports of the US surveillance system[23], a global pioneer in VAAE surveillance. The Brazilian study cited earlier also reported these symptoms as the most frequent, followed by persistent crying and seizures.[24] In Italy, Zanoni reported local reactions at the injection site as most frequent, followed by seizures.[30] Seizures did not figure among the most frequent symptoms in our study.

VAPP is a rare complication of OPV, first reported in the United States, with a rate of 1/3.2 million doses of OPV vaccine distributed.[31] When the polio eradication program was set up in Cuba in late 1962, a surveillance system was created for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) in children aged <15 years, predating the guidelines of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, which were endorsed by the World Health Assembly in 1988.[32] Since then, only 20 cases of VAPP have been reported in Cuba, the last diagnosed in 2006. The overall risk in Cuba, based on total OPV doses administered in the population aged <15 years, is 1/3,778,811 DA.[33] In another study published in Brazil in 2000, the estimated risk was higher (1/2.39 million doses).[34]

We used the Brighton Collaboration definitions for investigation and analysis of the two cases of anaphylaxis.[35] Vaccine-attributable anaphylaxis is a severe but rare event, estimated to occur in a range of 1 to 10/1,000,000 DA, depending on the vaccine studied; available data are limited and precise estimates are difficult to obtain.[36] A 1991–1997 study by Bohlke et al. in the United States identified 5 cases of anaphylaxis in 7.5 million DA (all vaccines included), yielding a risk of 0.65 cases/1,000,000 DA, concluding that risk of anaphylaxis was very low.[37] Our study found a rate some 15 times lower that that reported by Bohlke et al. and far below the range of 1 to 10/1,000,000 DA.

An 11-year study by the US VAERS reports deaths by study year and fatal event proportions ranging from 1.4 to 2.3%.[23] In our study, fatal events ranged from 0.0 to 0.1%. This corroborates the assertion that vaccination is still one of the health interventions with greater benefits than risks.

Nevertheless, our study shows that while vaccines are effective in preventing infectious diseases associated with high mortality, they are not risk free. Thus, it is essential to monitor their administration to determine actions to be taken to continue guaranteeing NIP’s success, defined by continued public trust and safety of the procedures and vaccines used, so that vaccination continues to yield the expected benefits with a minimum of risks.

The study shows that VAAE surveillance provides an important complement to information about NIP’s benefits in eliminating or dramatically reducing diseases that once killed and disabled children. It shows the scope of the risk side of the risk-benefit equation, allowing the public to appreciate the true net benefit of immunization for population health.[15–17]

Some limitations of the VAAE surveillance system placed constraints on this study. There was lack of systemwide computerized data processing that delayed reporting and analysis of adverse events. Only in severe cases were reports expedited to enable investigation within 24 hours of the event. The VAAE surveillance system has since been computerized in the provinces and municipalities, enabling information to flow more rapidly.

There were also issues with case definitions. Since its launch in 1999, the VAAE surveillance system has been working with standard reporting case definitions per 1997 WHO guidelines for VAAE surveillance for immunization program managers, updating them with WHO modifications.[18,38] The experience and reports of the US VAERS have also been taken into account.[39] Other institutions that have been working on the standardization of case definitions to develop a common international language are the Brighton Collaboration and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[35] These efforts have led to more systematic training of physicians and nurses to prevent adverse events associated with operational aspects of the program, over which vaccinators can and should have control.

CONCLUSIONS

This study sheds light on the type, extent and impact of vaccine- associated adverse events reported in Cuban children from 1999 to 2008. The low rates of severe vaccine-associated adverse events observed in this study underline the low risk of vaccination relative to its demonstrated benefits in Cuba. Decision-making for the continued success of the National Immunization Program is supported by reliable information from comprehensive national surveillance with standarized reporting, along with multidisciplinary expert analysis of rare and severe adverse events and program errors.