MEDICC Review: Cuba’s history is entwined with migration, entangled as everywhere with political, social and economic forces of the times. Let’s start with the “now.” Can you give us a picture of current migration trends and how these emerged?

Antonio Aja: The whole world is facing the challenge of migration. Cuba is no exception, but has some peculiarities. Like many developing nations, we have few resources and limited alternative energy options. Additionally, for over 50 years, we have lived in conflict with the USA, the world’s richest country and our neighbor. After surviving the 1990s, [following the collapse of the socialist bloc and tightening of the US embargo], we stayed our essential course, but also embarked on a complete redesign of almost every aspect of our society, our socialism.

Development at this most difficult point requires major investment. We need substantial capital investment. Yet, despite renewed relations, we’re still in a face-off with the country that holds the reins of global finance, the embargo presenting a real obstacle that makes this much harder.

At the same time, Cuba’s social and educational policies over the years trained professionals beyond our own needs, who became educated intellectuals, professors, engineers. But our economy is not yet robust enough to provide the underpinning needed to support them.

Taken together, factors like these not only impact our daily lives but also the push–pull of emigration. For example, in the current situation, however much salary raises are needed and projected, they’re simply not possible across the board. And so, young professionals are the ones who are emigrating.

This is once again complicated by the fact that most of our emigrants go to the United States, one of the world’s most developed countries—where over a million Cubans or Cuban descendants have developed a strong network, and where laws favor Cubans over other immigrant groups. The result? After Cuba has made the investment to train our young professionals, we become exporters of their talent.

And for those who say remittances are a solution [for the country’s economic advancement], I would argue that remittances don’t develop a country. Only people do.

Finally, because Cuban social policies, public health in particular, have extended longevity, while birth rates are lower than required to replace population, the outflow of younger emigrants also contributes to the aging of Cuban society. The changing population pyramid, with nearly 20% of Cubans already 60 or older, means there are proportionately fewer people of working age to support children and the elderly, and to drive the economy forward.

MEDICC Review: Cuban emigration, especially to the USA, has been a real political hot potato over the years in both countries. You mentioned that US laws favor Cubans over other immigrants. What does this mean?

Antonio Aja: The Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 provides automatic entry and subsidies to undocumented Cubans who land in the USA—and only to Cubans—under the condition that they declare themselves “political refugees.” If you compare their status to that of Central Americans, for example, you start to see the injustice.

The Cuban Adjustment Act has been—and is—a real problem, even when the US and Cuban governments have reached migration accords, which they have done twice, in 1984 and 1994. It encourages people who want to leave to reach the USA through third countries or by sea, which is dangerous, instead of applying through the regular US visa process.

But the whole history of Cuban migration to the United States is fraught with politics, even before the Cuban revolution of 1959. And certainly more so afterwards.

MEDICC Review: Can you walk us through the different stages of Cuban migration and how this is revealed?

Antonio Aja: Until World War II, and in Cuba’s case until the 1930s, Latin America was still on the receiving end of immigration. Over time, immigrants became more selective: Germans made their way to Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, while Brazil was receiving Japanese and Portuguese. Meanwhile, Spanish were still migrating to Cuba. After about 1930, Cubans began to migrate in greater numbers, joining other Latin Americans especially after the War, when the global pattern of migration changed. Developing-country nationals began to move to developed countries, reversing earlier migration trends. This, in great part, began as a strategy by the western powers to revitalize a devastated Western Europe.

In the 1960s and 1970s, more Latin Americans began to leave the region for economic and political reasons, and mainly for the United States because of its economic and cultural influence and its geographic proximity. Also at that time, the USA opened its doors further to immigrants from this hemisphere. Today, of course, Latinos have become the number one minority in the United States.

In the particular case of Cuba, we’re also a nation of immigrants. Not just Spanish in earlier centuries, but also Africans who were forced into slavery, as well as Chinese, Japanese, and others in smaller numbers. In fact, Asians were brought to substitute Africans in the Cuban labor force because the Spanish feared the influence of “negritude.”

But, when not forced, migration patterns follow the path of history, of social networks already created. That has been so for Cuba, too. So from 1930 to 1959, Cuba became a source country for migration, above all to the USA, Spain, Venezuela and Puerto Rico. Mainly, this was economic emigration, but also political. Politics has always been part of this coming and going, and Cuba’s island status plays a part in the constant movement of its population, too.

MEDICC Review: And after the 1959 revolution?

Antonio Aja: By 1958, there were about 125,000 Cuban residents in the USA, including immigrants and their descendants, according the US census. The revolution provoked an almost immediate shift in migration patterns: for the first time, the upper classes migrated, the ones whose economic and political power was displaced in Cuba, who were associated either with US interests or with Batista. At the same time—and here is where it becomes even more political—successive US governments began to use the ‘exiles’ to mount open, and sometimes violent, opposition to the Cuban government from abroad. Witness Playa Girón (Bay of Pigs), the multiple assassination attempts and so on.

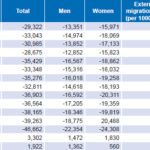

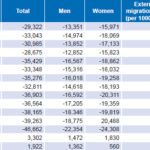

Cuba: Net Migration 2000–2014*

*In 2013, a new law took effect, making it possible for those leaving the country for up to two years to maintain Cuban residency.

Source: National Statistics Bureau (CU). Anuario Demográfico de Cuba. Habana. 2014.

This raises a second difference characterizing the waves of migration after 1959: the source and destination countries’ governments were completely, unremittingly at odds. And this was reflected at social, individual and family levels. Emigration became in essence a political phenomenon, a function of this reality. And on the Cuban government side, for the reasons mentioned, it became a matter of national security.

Finally, the numbers of people migrating post 1959 were also greater than previous years. After 1970, economic reasons predominated, but not exclusively. In sum, from 1960 to 2005, the US Census registered 946,716 Cuban-born residents in the USA; the number reached over one million by 2010.

MEDICC Review: Then there were decades of back-and-forth with both the USA and Cuba giving more or less opportunity for Cuban migration at different points…a subject you address in depth in your book Al cruzar las fronteras,* but certainly too complex for this interview. Can we once again jump to the present?

Antonio Aja: Of course. In 2013, the Cuban government adopted a new migration law, in which virtually every Cuban citizen has the right to travel abroad for any purpose. It also provided for people to live abroad for up to two years without losing their residency status in Cuba, and even then, with options for extension of that period. This is quite important and a first, because now Cubans can go back and forth, and they maintain their rights in Cuba, including social and other benefits such as free health care and education.

Migration conversations with the US government are also continuing, in the context of renewed relations, in an attempt to move beyond the 1994 migration accords that are still in effect between the two countries.

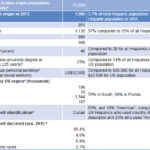

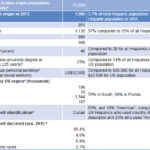

Hispanic and Cuban-Origin Population in the United States

a Source: Lopez G. Hispanics of Cuban Origin in the United States, 2013. Statistical Profile. Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends. September 15, 2015. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/09/15/hispanics-of-cuban-origin-in-the-united-states-2013/

b Source: Hispanic Population: 2010. Census Brief. May, 2011. Available at: https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf

MEDICC Review: Recently, Cuba’s Ministry of Public Health also authorized return to the island and to their professions of health workers who had left the country, even permanently at the time. Or under the so-called Medical Parole Program instituted under President George W. Bush. What can we expect from this in terms of reversing the brain drain you referred to earlier?

Antonio Aja: It’s interesting that young people who are professionals in various fields increasingly characterize the emigration profile of Cubans moving abroad. And their educational levels contribute to the fact that Cubans in the USA are better educated than most of the Latino population, and garner better salaries—70% of all Cuban-born US residents have at least a high school education. This, despite the fact that there are considerable socioeconomic disparities within the Cuban-American population today.

The US Medical Parole Program you mentioned began in 2006 and offers visas to any Cuban health worker who has volunteered abroad under a Cuban Health Ministry program, and leaves his or her post. This not only affects Cuba, but also the countries and people where these health professionals were working, mainly in underserved areas of Africa, the Americas and Asia. However, it does not guarantee them employment in their fields in the USA.

Concerning health workers returning to Cuba: the decision not only authorizes them to return, but commits to ensuring them employment similar to the one they had when they emigrated. We’ll have to wait and see what the results will be. Historically, migrants become accustomed to the living conditions in the place where they have relocated, so this is one factor to be considered and in this context, Cuba’s development will play a role over time.

In any case, with the new Cuban regulations, both professionals in all fields, and others, have opportunities to come and go: spend part of their time abroad, perhaps increasing their earnings or savings, then return home for another portion of time. This “circular” or “transnational” migration could be very important to mitigate the brain drain in Cuba’s case, and also for investment. Emigrants can play an important part in a country’s development, its economy, and thus Cuba’s own investment in human capital wouldn’t be entirely lost. Take a look at China for example. We need macro and micro investment. And we need the inspiration of younger generations.

We aren’t going to stop migration; it’s a fact in our world. But of necessity we’re changing our thinking, which is a good thing. We, and those leaving, if only temporarily, are moving away from the word “emigrant”, and certainly from “exile.” We’re beginning to identify ourselves as we are: Cubans.

And frankly, in any scenario, all Cubans need the US embargo lifted in order for our country to prosper and develop.

*Aja A. Al cruzar las fronteras. Editorial Nuevo Milenio, La Habana. 2014. Spanish.