INTRODUCTION

The HIV/AIDS epidemic extends worldwide and threatens human survival. When the first cases were reported in 1981, no one suspected that the world would be faced not only with one of history’s most serious health problems, but also one of its gravest social problems. HIV/AIDS has destabilized families, resulting in illness or death of some and abandonment of others; and it has meant extreme economic losses for various countries, affected by, among other things, the magnitude of death rates in their economically active population.[1]

According to estimates by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization, at the beginning of 2009 over 33 million people were living with HIV/AIDS, 50% of them women. Among adults in the Caribbean, AIDS is one of the main causes of death, and the region has the highest HIV prevalence in the world after Sub-Saharan Africa.[2] Cuba’s estimated 0.1% HIV prevalence in adults is considered low, although incidence is rising.[2,3] From 1986 through 2009, HIV was diagnosed in 12,217 persons; of those, 4,938 developed AIDS; and 2,127 have died from the disease. In Cuba, men are 81% of persons with HIV/AIDS; and of those, 72% are men who have sex with men, the latter the primary means of HIV transmission.[4,5]

In late 1985, the Ministry of Public Health established the National HIV/AIDS Program,[6] its launch facilitated by the existence of a comprehensive and universally accessible public health system.[7]

Beginning in 2001, the Cuban government decided to produce generic antiretrovirals, to ensure access to free antiretroviral therapy for all HIV/AIDS patients who needed it, aiming to increase overall survival and decrease opportunistic infections.[7]

As long as there is no cure for AIDS, the only effective means of containing its spread is prevention, primarily through public education.[8] Cuba has excelled in preventive actions, their effectiveness improved by involving persons living with HIV/AIDS.[9]

The first sanatorium providing comprehensive in-patient care for people infected with HIV was established in 1986 in Santiago de Las Vegas, Havana City province, an approach later extended to the entire country. In 1994, ambulatory care was established as an alternative[7] and by 2006, the main focus had shifted to strengthening decentralized delivery of comprehensive care at the community level through primary health care.

The AIDS Prevention Group (GPSIDA, its Spanish acronym) emerged in 1988 at the Santiago de Las Vegas Sanatorium. In 1991, GPSIDA was officially constituted as a community-based organization of both seropositive and seronegative members. Its main purpose is to support the National HIV/AIDS Program in its attempts to curb the rising (albeit slowly) incidence of HIV infection. GPSIDA’s activities are intended to educate the public, prevent new infections, and support people living with HIV/AIDS and their families. Today, 16 GPSIDA groups are active throughout Cuba, with over 300 members and 500 collaborators. They are organized at the local and provincial levels, and rely on a strengthened communications and exchange network of health professionals and technicians, psychologists, sociologists, health promoters, counselors, and facilitators.[10] GPSIDA’s Memorias, affiliated with the International NAMES Project,[11] is one of the group’s programs aimed at prevention and public awareness of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS.

The NAMES Project was created in 1985 in the United States to remember those who had died of AIDS, make public the devastating impact of the epidemic, and increase public awareness of HIV/AIDS issues.[12] In 1987, the first quilt panel was made, six feet long and three feet wide, to evoke the dimensions of a coffin. Thousands of panels were added in short order and the quilt has been exhibited nationally and internationally.[13]

INTERVENTION

In 1996, GPSIDA began an exchange with Elena Schwolsky, a US nurse who had considerable experience in HIV/AIDS prevention, and specifically with the NAMES Project. The idea of adapting the NAMES experience to Cuban customs and culture arose during a workshop she led for people with HIV/AIDS in the Santiago de Las Vegas Sanatorium.[14] The resulting project was called Memorias(“memories”).[15]

Memorias aims to:

- contribute to effective prevention activities, particularly the educational component of the National HIV/AIDS Program;

- contribute to understanding the consequences of HIV/AIDS for society;

- promote solidarity with, and sensitivity towards, those affected by HIV/AIDS;

- put a human face on HIV/AIDS statistics, making people understand that it touches them as well, and that they too could be at risk of infection; and

- remember all those who have died from AIDS.

Memorias carries out its work in two main ways. First, it convenes sessions and workshops with family members, friends, colleagues, and partners of the deceased, to explain the project’s objectives, train participants in quilt-making, create a reflective space for discussion of HIV/AIDS, and begin sewing the panels. Then, public exhibitions are organized to put the quilts on display.

Figure 1: Quilt ceremony, Mariana Grajales Park, Havana, December 1, 2007

Source: GPSIDA archives

The quilts, made of eight panels sewn together in a square, contain words, photos, and personal effects of loved ones who have died of AIDS. The creative design is the work of participants, taking into account the wishes of the family. Family members are asked for their consent—and, if willing, participation—before any panel is begun.

Workshops The impetus for a new panel comes from family members, friends, partners or colleagues to honor the memory of a person who has died of AIDS and to serve as a prevention message for the general public, to avoid more infection and deaths. Participants provide all the necessary materials, including fabric swatches and thread, and any other material resistant to wear. Panelmakers add the name, birth and death dates of the person the panel honors, including details and phrases to personalize the panel and sensitize viewers.

Public Exhibits A Memorias exhibit begins with a ceremony in which eight people unfold each quilt while another reads the names of the deceased (Figure 1).

Surnames are not used, because mentioning “Alfredo” is intended to evoke all Alfredos, “María” all Marías. If someone hears their first name mentioned, they are more likely to identify with the deceased, and realize that it might just as well be their name on the quilt.[16] Once the quilts are spread out, visitors are invited to take a closer look (Figure 2).

As the reading of names continues, messages are also inserted about individual responsibility; sensitivity toward those who are infected or affected; stable, loving relationships; and respect for others. Educational materials are also handed out. Generally, exhibits are held in neighborhoods, schools and other places where community members gather. Local leaders invite people to participate, creating a space to exchange thoughts about HIV/AIDS.

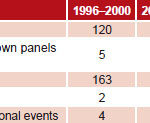

The first panel made was exhibited on the Santiago de Las Vegas Sanatorium’s tenth anniversary in 1996, and was dedicated to deceased members of GPSIDA. In October the same year, the first seven Cuban quilts participated in an international exhibit of the NAMES Project in Washington, DC; and in December, in another at Havana’s Pabellón Cuba exhibit center.

In 1997, a Memorias international display was held in the Capitol building’s gardens in Havana, with quilts from the United States and Venezuela as well as Cuba. In December the same year, a national exhibit toured the entire country, with panels made in the provinces added during the tour, prompting provincial GPSIDAs to work on their own quilts for prevention activities.

In 1998, Memorias joined the European tour of the NAMES Project in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. During 1999, there was a second national tour to all of Cuba’s provincial capitals; by then there were 120 panels, and every province organized multiple prevention activities to coincide with the exhibit.

Figure 2: Memorias Project exhibit, November 22, 2008, Santa Clara, Villa Clara

Source: GPSIDA archives

From 1999 forward, the project continued to grow, as did the number of panels contributed by each province. Exhibits have been held in schools, universities, workplaces, military units, public squares, parks, and communities (Table 1).[17–20] The Memorias Project is also used in World AIDS Day activities, event openings, meetings, and workshops,[21–23] such as the Pedro Kourí Tropical Medicine Institute International AIDS Event (Havana, 2000); the 2nd Latin American and Caribbean Forum on HIV/AIDS (Havana, 2003); the Solidays Festival (Paris, 2003); and the CHANGO (Spanish NGO) HIV/AIDS Workshop (Madrid, 2005). Since 2004, the Memorias exhibit has toured Cuba annually. Support for these activities is reflected in Ministry of Public Health planning documents, emphasizing a broad multisector response to HIV/AIDS.[24]

Table 1: Memorias Project panels and exhibits, 1996–2009

Source: GPSIDA archives

During the exhibits, visitors are interviewed to ascertain their opinions, impressions, and reflections after they view the quilts. The semi-structured interviews use both open-ended and closed questions. Responses are analyzed periodically to inform and improve GPSIDA’s work and evaluate the project’s impact on the public.

RESULTS

Some authors report use of the commemorative quilt helps people deal with pain and loss and thus diminishes depression following a loved one’s death.[25] In GPSIDA’s experience, Memorias‘ impact varies depending on the kinds of people involved.

The following are examples of thoughts expressed by relatives and loved ones of people with HIV/AIDS, interviewed while they were working on quilt panels:

- I can’t bring him back, but being here with all of you, it brings back my good memories of him; and I feel as if he were here to remind us all to be careful, to protect ourselves.—Partner of a young man who died of AIDS at age 25.

- Every time I help unfold the quilts, I feel I am contributing to fighting the epidemic. It’s as if I were doing what I couldn’t with my daughter. I remember her and help others who might also be my children.—Mother of a young woman who died of AIDS at age 22.

- The pain never stops, it never goes away completely, memory brings it back. But here, it’s less, as I see all of you struggling so that others don’t get sick. It gives me the energy to go on.—Sister of a man who died of AIDS at age 31.

- Whenever I hear about an exhibit, I come and put flowers on my daughter’s panel. It feels more real than going to the cemetery. I see her more vividly. I am surrounded by people; they ask, and I give them my advice, and then I feel much better.—Mother of a young woman who died of AIDS at age 23.

When people with HIV participate in workshops and exhibits, they convey to others the emotional, physical, family, and social challenges of living with HIV/AIDS,[26] GPSIDA health promoters organize the exhibits and share with the general public their experiences, challenges, anguish, and their dedication to prevention. Here are some comments from interviews with these GPSIDA activists:

- “I’d like to be here every day to let people know that I didn’t protect myself, I wasn’t careful. I didn’t believe that AIDS existed and now I am sick; I take lots of pills and I don’t know how much time I have left. That’s why I want others to take care of themselves.”—Man with AIDS, health promoter with Memorias Project, age 38.

- “When I unfold the quilts, I get very emotional. I remember everyone I knew with a mixture of pain and nostalgia, and that gives me a lot of strength to convince young people to protect themselves, so that they don’t suffer. But above all, so that we don’t lose more young lives.”—HIV-positive man, Memorias Project promoter, age 40.

- “When I see these smiling, happy girls, flirting with boys, it reminds me of myself, of who I was. So I go and talk with them, and tell them that this sick woman they see today was once a smiling girl just like them. I tell them to be very careful, that they can do what they want, but responsibly.”—Woman with AIDS, health promoter with Memorias Project, age 35.

Memorias exhibits attract the general public: children, adolescents, and young and older adults, who gather to learn about a different life experience that helps them reflect on their own. The Memorias Project illustrates the importance of the epidemic, and increases public awareness of HIV/AIDS and the need for people to protect themselves. This is consistent with various studies that suggest such commemorative AIDS quilt exhibits reinforce and clarify messages designed to promote healthier behavior,[27] encourage people to become more informed, openly discuss HIV/AIDS,[28] and generally contribute to preventing new infections.[29] Memorias Project exhibits stir up strong emotions, which in turn prompt reflections on HIV/AIDS prevention, as these viewer comments illustrate:

- This exhibit is educational, but also highly experiential. These are real situations. The display manages to communicate feelings and makes us think, because we see up close the complex problems associated with this disease.—Woman from Havana City.

- I have known about AIDS for some years, but I had never experienced anything like this. It has touched me very deeply. I wish the best of health to those who are ill. This makes us more aware; it should be done more often.—Man from Havana City.

- Looking at these quilts, I realize that AIDS can be anywhere and we should always protect ourselves.—Woman from Matanzas.

- This exhibit stirs the emotions of students and colleagues; it brings us face-to-face with the problem and makes us think.—Teacher from Ciego de Ávila.

- This is very powerful, it hurts. Because anyone who comes here sees that other people have died because of this virus; here, a simple image moves you more than any words.—Man from Santiago de Cuba.

- There are friends who are rejected because of this disease. But no—if they’re our friends, we have to take care of them, so they know we’re their friends in bad times as well as good.—Man from Guantánamo.

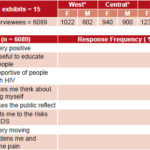

Opinions collected from people who have seen Memorias exhibits as they tour the country (Table 2) indicate that the quilts are useful educational tools, that they encourage reflection on the risks of HIV infection and solidarity with people who are infected. Participants see the exhibits as a positive experience, although they arouse feelings of sadness and pain.

Table 2: Memorias Project national exhibits: interviewees by region, sex, and most frequent opinions

*West: provinces of Havana, Havana City, Matanzas, and Pinar del Río. Central: provinces of Camagüey, Cienfuegos, Ciego de Avila, Sancti Spíritus, and Villa Clara. East: provinces of Granma, Guantánamo, Holguín, Las Tunas, and Santiago de Cuba. Source: Memorias Project, GPSIDA