MEDICC Review: How does UNICEF’s work in Cuba differ from its work elsewhere?

José Juan Ortiz: Cuba is a country of limited economic development, but high human development, so the fundamental difference between our work in Cuba and other UNICEF member countries is that our priorities are different. In other countries, the main health priority is surviving infancy and the top educational priority is ensuring children go to school. This doesn’t apply here since these goals were achieved 50 years ago, prompting a somewhat different strategy for our Cuba country program. Instead of implementing specific projects addressing these issues as we do elsewhere, our work in Cuba is organized to support fulfillment of the Convention on the Rights of the Child at different stages of childhood development.

These stages are divided into early childhood (0–5 years), childhood (6–11 years), and adolescence (12–18). Health, education, and cultural programs cut across all ages, but a health program for a young child, for instance, is not the same as for an adolescent, which is why we support efforts within specific age groups instead of issue-based macro projects.

MEDICC Review: Regarding Cuba’s youngest, newborns to 5-year-olds: what are UNICEF’s main programs in the area of health?

José Juan Ortiz: There are two: breastfeeding and anemia. In terms of anemia, we work with a consortium of United Nations agencies fortifying baby food with essential micronutrients, primarily iron. [Iron-deficiency anemia is found in 30–45% of Cuban infants aged 6 to 23 months; 25–35% of reproductive-age women; and 24% of pregnant women in their 3rd trimester.—Eds.].[1] This program is aimed at pregnant women and children aged 0–3 years and is implemented on a national level, with an emphasis on the most vulnerable five eastern provinces and Pinar del Río. UNICEF coordinates the program in collaboration with the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (production), World Food Programme (distribution), UN Development Programme (distribution and stimulation of production), and the World Health Organization (WHO). Of course, we work closely with the Cuban Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP) on this and other programs.

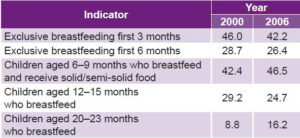

Breastfeeding is an area of concern both for UNICEF and the Cuban government. Despite all our outreach work and educational campaigns, we have not been able to increase the percentage of women exclusively breastfeeding their babies through the first 6 months of life. This is the global standard set by UNICEF and WHO, and in Cuba we’ve seen a slight decline in exclusive breastfeeding (see box).

We’re not entirely sure of the causes, especially since all Cuban maternity hospitals are UNICEF/WHO-certified “baby friendly,” meaning they meet all the personnel, infrastructure, and educational requirements for preparing new mothers to breastfeed. Furthermore, all Cuban mothers are guaranteed 12 months maternity leave. As far as we can figure, the tendency to discontinue breastfeeding early is caused, in part, by the evolution of the modern Cuban woman, who enjoys access to breast milk substitutes, considerable family support for child care, and personal and professional independence.

Two other areas in which UNICEF Cuba works to improve the health of 0–5 year-olds are maternity homes, where we provide comprehensive support for the renovation of the homes themselves and professional capacity-building, and the early child development program known as Educa a Tu Hijo (Educate your Child).

Percentage of Breastfed Children in Cuba, 2000 & 2006

Source: Cuba. Encuesta de Indicadores Múltiples por Conglomerados 2006. Ministry of Public Health (CU) National Medical Records and Health Statistics Bureau, UNICEF, 2006 Dec.

MEDICC Review: The British Medical Journal recently highlighted Educa a Tu Hijo as an example of an intersectoral program that is “shifting the norms of early child development.” Can you explain this program and how it evolved?

José Juan Ortiz: Cuba had been looking at ways to institutionalize early childhood learning when the economic crisis known as the Special Period hit in the early 1990s. Whereas they had been focusing on establishing more pre-schools throughout the country, the economic collapse made that impossible, so in 1992, UNICEF, along with the Ministry of Education and the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), launched a pilot Educa a Tu Hijo program. The pilot was based on Cuban studies of early childhood learning and the role played by educational initiatives in the psycho-emotional development of 0–6 year-olds, which found that such initiatives are most effective when based on active participation by the child’s family and community. It’s a simple concept really: providing active and loving stimulation to young children, by paying attention to them, being affectionate, playing games, practicing sports and dancing, improves psycho-emotional development.

In practice, families—parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, etc.—bring their children to a community space two or three times a week for two hours at a time where volunteers help them to learn and play in a safe, loving environment. You’ll find Educa a Tu Hijo in the most incredible places. Whereas in a Havana neighborhood, classes may be held in a community cultural center, in other areas they may be held on a front porch or backyard, even under a big tree in the local park—anywhere local people gather.

One of the reasons Educa a Tu Hijo is so innovative is that it translates seamlessly from city to countryside, requiring few resources other than those already in the community. Also, like the best Cuban programs, it is also intersectoral, combining health, education and sports through the work of the FMC, the community block associations, the National Sports and Recreation Institute, and family doctors. The results have been spectacular, with 70% of Cuban children participating in Educa a Tu Hijo before entering kindergarten. The program has been implemented in five other Latin American countries,[2] and UNICEF is recommending that it be adapted to other countries as well.

It’s interesting because Educa a Tu Hijo is often considered an educational program, but it isn’t. Rather, it’s a development program focusing on integrating both the physical and mental health development of young children, which when complemented by Cuba’s dynamic social structure, delivers positive results in children’s intellectual development.

MEDICC Review: Where do you see challenges for UNICEF’s work in Cuba?

José Juan Ortiz: Teen pregnancy. Cuba has quality sex education, young people have access to birth control and family planning, and there’s a culture of permissiveness in the best sense of the word, meaning Cuban teenagers can have safe sex at home, but we still haven’t been able to definitively lower teen pregnancy rates. In some provinces the rate goes up, in others it goes down, but despite programs and campaigns focusing on the problem, we haven’t seen a uniform decrease in teen pregnancy.[3]

This year, UNICEF is launching targeted campaigns to address this concern by adapting our communications strategy to use a peer group approach, with teens talking to other teens about pregnancy. A 15-year-old talking about her experience as a teen mother—how radically her life has changed, how she can’t finish school, for example—is a much more effective way to get the message across. Traditionally the message comes down from above, with teens hearing it from parents, teachers, MINSAP, whomever. Our goal now is to communicate horizontally, with teens telling their peers: ‘you can say no, you can negotiate with your partners’ and ‘being a parent is much more complex than just being biologically able to have a baby; giving birth doesn’t automatically make you a responsible parent.’ It’s an educational process above all else.

MEDICC Review: In 2008, Cuba was hit by three hurricanes that caused damages estimated at 20% of the country’s GDP. I know you have extensive disaster response experience and wonder if UNICEF was involved in recovery efforts?

José Juan Ortiz: Yes. In the immediate recovery period, the Cuban government asked for our help in ensuring safe drinking water by providing water tanks for homes and apartment buildings, and helping to repair municipal water systems. In the next phase, two months or so later, we began focusing on repairing schools. As you know, schools function as hurricane shelters here. So those schools that were not flattened or damaged by the hurricanes, were filled with evacuated families. Still, children in hurricane-affected areas were back in school the day after the storm(s) had passed—whether classes were held in a home or a cafeteria. These children, even those temporarily housed in shelters, were back learning the next day. This has both educational and mental health benefits since the children are right back in their normal, daily routine: we go to school at 8 in the morning, we sing the national anthem, and we begin classes. In the fantastic world of children, the tragedy loses some of its magnitude and it becomes almost a game once they recover their routine.

MEDICC Review: Amnesty International recently issued a report titled The US Embargo against Cuba: Its Impact on Economic & Social Rights, citing the policy’s effect on the work of international agencies. Have you found the embargo adversely affecting your work?

José Juan Ortiz: The embargo affects everyone in Cuba, personally and professionally. Many of the materials that UNICEF needs for its work with Cuban children and youth come from the United States, but we are prohibited from bringing them here. To give you a concrete example, if we need baseballs for an after-school sports program, ideally, we would buy them in Miami, but we can’t, due to the embargo. Instead, we have to buy them in Taiwan, where they are more expensive. Plus, we have to pay for long-distance shipping, so in the end we only have the budget to buy five baseballs. And this is repeated across the board with vaccines, medicines, pediatric anesthesia and heart valves…That is to say, the embargo has a direct and severe impact on the health of Cuban children.

MEDICC Review: What can we learn from Cuban initiatives to protect children’s rights?

José Juan Ortiz: I always say that applying the tenets of the Convention of the Rights of the Child isn’t a question of resources, but rather one of political will. Cuba has demonstrated that a country doesn’t need to be rich to protect children’s rights. The Convention has been in place for 20 years and we’re still talking about hundreds of millions of children living in the street, not in school, or enslaved as laborers or sex workers, but not one of those children is Cuban and that’s due to the government’s political will to create a protective, rights-based environment. In Cuba, this protective environment is based in the family and the community, but extends to the provincial, national, and ultimately international level in cooperation with agencies like UNICEF. By guaranteeing social and community development, the Cuban government has shown the political will to provide for and protect children. This is also what has allowed Cuba to achieve health outcomes on par with the world’s most developed countries.