INTRODUCTION

Chronic non-communicable diseases (NCD) represent a serious health problem, contributing greatly to the global burden of morbidity, mortality and disability.[1] They are the leading causes of death in adults in most countries,[2] accounting for an estimated 63% of deaths worldwide in 2015.[2]

NCDs are also the leading causes of death and disability in the Americas, accounting for over 3.9 million deaths annually, 75% of deaths in the region.[3] In Cuba, NCDs account for 76% of deaths, and NCD-related mortality is 10 times the combined rates for communicable diseases and maternal, perinatal and nutritional causes.[1]

Metabolic syndrome comprises a set of NCD risk factors: hypertension, dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance and central obesity. Most metabolic syndrome patients have insulin resistance and a greater risk of atherosclerosis and its sequelae.[4]

Most of these risk factors are preventable and controllable using cost-effective nonpharmacological measures, aimed primarily at lifestyle changes that include a healthy diet, increased physical activity and elimination of harmful habits such as smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. Controlling them may also require pharmacological measures.[5,6]

The first step in vulnerable population groups is to identify metabolic syndrome risk factors. Determining their prevalence rates enables assessment of the magnitude of metabolic syndrome as a public health problem, as a basis for better allocation of material and human resources.

Previously published papers on metabolic syndrome’s frequency and its component risk factors in Holguín Province focused on only a few health areas (primary health care catchment areas) and studied relatively small samples, limiting extrapolation of their results.[7–9] It is important to determine prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors in adults in representative samples from the province, the objective of this research.

METHODS

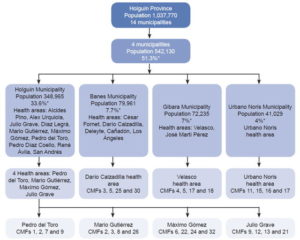

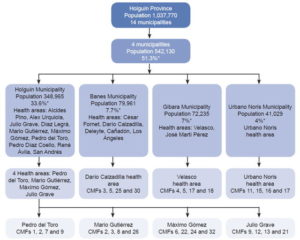

Setting With an area of 9293 km2 (8.5% of Cuba) the northeastern province of Holguín has an estimated population of 1,037,770 (9.3% of Cuba’s), with the sexes evenly distributed and some 789,265 persons (76.1%) aged ≥20 years. The province has 46 health areas (each served by a community-based polyclinic and the neighborhood family doctor-and-nurse offices it supervises) in 14 municipalities, the most populous of which is Holguín, with 348,965 residents, 33.6% of the provincial population.[10]

Design and sampling strategy This was a descriptive study. A complex sampling strategy was used to ensure a representative population from the province and minimize selection bias. In the first stage, simple random sampling (SRS) was used to select 4 of the province’s 14 municipalities—Holguín, Gibara, Urbano Noris and Banes—comprising 51.3% of the population. Second-stage units were chosen by SRS among the 18 health areas in the selected municipalities: 1 health area for each of the smaller municipalities and 4 from Holguín Municipality, home to over 30% of the sample. For third-stage units, 4 family doctor-and-nurse offices from each health area were chosen by SRS, for a total of 28 (Figure 1).

SRS was used to select participants from the chosen doctor-and-nurse offices, progressively added to the complex sample from 2004 through 2013. The final sample consisted of 2085 adults aged ≥20 years. The desired sample size was calculated using EPIDAT 3.1 (Xunta de Galicia, Spain, PAHO, 2006) according to WHO criteria for observational studies,[11] specifying an expected proportion of 0.30, 95% confidence interval (CI), 3% precision and design effect of 2.3.

Figure 1:Sampling flow chart

CMF: family doctor-and-nurse office SRS: simple random sampling

*of provincial population

Variables and procedures Venous blood samples were taken following 12–14 hours fasting and at least three days of a low-fat diet. Most test reagents were produced domestically (EPB Carlos J. Finlay, Havana): blood glucose, Rapiglucotest; triglycerides, Triglitest; total cholesterol, Colestest; HDL cholesterol, C-HDL Inmuno FS. LDL cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald formula.[12] Laboratory tests were performed in duplicate by the health areas’ chemistry laboratories and the Applied Biochemistry Laboratory at the Medical University of Holguín.

Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed according to the National Cholesterol Education Program (ATP-III) by presence of three or more of the following criteria:[13]

- fasting blood glucose ≥5.55 mmol/L (≥100 mg/dL) or treatment for diabetes

- fasting plasma triglycerides ≥1.70 mmol/L (≥50 mg/dL)

- HDL cholesterol <1.03 mmol/L (<40 mg/dL) for men and <1.29 mmol/L (<50 mg/dL) for women

- systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic ≥85 mmHg or antihypertensive treatment

- abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥102 cm for men, ≥88 cm for women)

Prediabetes and diabetes were classified according to American Diabetes Association guidelines.[14] Cuban guidelines were followed to determine blood pressure and hypertension classification.[15] Weight and height were determined using a calibrated scale and stadiometer, with precision of 0.1 kg and 1 cm, respectively. Body mass index was calculated by dividing weight in kg by height in m2. Waist circumference was measured above the iliac crest and the mid-axillary line, with the patient standing, and a precision of 0.5 cm.

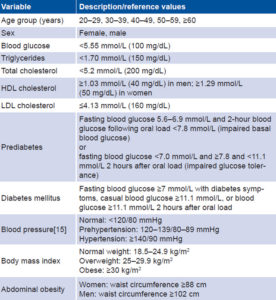

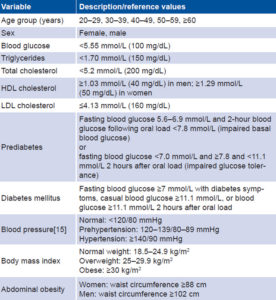

All measurements were done twice by technicians and other personnel previously trained for the study, taking the average of the two measurements. Table 1 describes study variables and lists reference values.

Analysis EPIDAT 3.1 was used to calculate risk factor prevalence rates (percentages with 95% CI). Because of the long data collection period, rates were not age adjusted.

Ethics The study was approved by the Scientific Council and Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Holguín, the institution that funded the research (code 0804099). Participants provided written informed consent and anonymity preserved.

RESULTS

Mean age was 45 years (SD 12.0, 95% CI 44.5–45.5, range 20–94). Mean age in women was 45.4 years (SD 12.0, 95% CI 44.7–46.1, range 20–94) and in men 44.4 years, (SD 12.1, 95% CI 43.6–45.2, range 20–86).

Crude metabolic syndrome prevalence was 27.2% (CI 25.3%–29.1%). Rates for groups aged 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59 and ≥60 years were 10.2% (CI 4.9%–15.5%), 13.2% (CI 10.3%–16.1%), 22.7% (CI 19.6%–25.8%), 36.6% (CI 32.0%–41.2%), and 56.6% (CI 50.9%–62.3%), respectively.

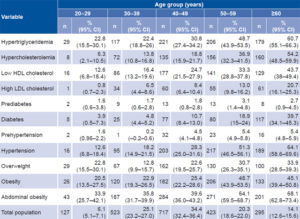

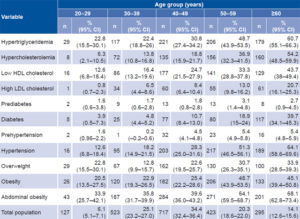

Prevalence rates for metabolic syndrome risk factors are listed by age group in Table 2 and by sex in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

The high prevalence rates for metabolic syndrome risk factors found in this study may be related to underreporting of patients with occult disease. For example, the US CDC found 26% of adults in the USA had multiple chronic diseases.[16] Population studies in the USA have found high prevalence of risk factors and undiagnosed NCDs, supporting the importance of active searching for these factors in the general population and in higher-risk groups in particular.[17]

Table 1: Variables

Table 2: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors by age group, Holguín Province, Cuba (2004–2013)

CI: confidence interval

Variability in prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors is strikingly wide in Cuban and international studies, depending on criteria used, sample size, and genetic and environmental factors, which differ among countries and regions.[18–39] Most studies agree that rates increase with aging. Genetic risk factors explain 40%–50% of prevalence variability by ethnic group.[40] Environmental factors are mainly lifestyle related, such as diet, physical activity and harmful substance use.

The higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors in older adults in this study could be explained by the metabolic and hormonal changes of aging responsible for high morbidity in this stage of life; these results coincide in part with those of other studies in the Middle East and North Africa.[31,41]

Hypercholesterolemia is an independent risk factor for metabolic syndrome, in which dyslipidemia is characterized by hypertriglyceridemia, high LDL cholesterol and decreasing HDL cholesterol.[4] The high rates of dyslipidemia we found are consistent with the variability and high prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors.

This study found type 2 diabetes rates in Holguín Province higher than those reported in 2013 for the province (3.4%) and Cuba (5.4%).[42] Other authors, such as Bustillo[21] in Sancti Spíritus, found a diabetes prevalence of 13.6%, mainly type 2, starting in the fifth decade of life and predominantly in women; the figure was even higher in a primary care setting in Pinar del Río Province.[18]

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes also varies around the world. The Middle East and North Africa region have one of the highest diabetes rates, at 9.2%, led by Saudi Arabia with 23.8% and Kuwait with 23.1%.[41] In Europe, 2013 prevalence was 8.5%, with rates in different countries varying from 2.4% to 14.9%.[43] Diabetes prevalence also varies in Latin America, at 6% in Mexico,[30] 6.3% in Brazil,[3] 9.5% in Costa Rica[3] and 9.6% in Argentina.[5]

Table 3: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors by sex, Holguín Province, Cuba (2004–2013)

CI: confidence interval

asignificant difference between groups (p = 0.05%)

Hypertension prevalence rates were also found to be higher than those previously reported for the province (21.3%) and Cuba (21.5%), while concurring on predominance of women and older adults.[44] However, Cuba’s Third National Survey on Risk Factors and Chronic Diseases found higher hypertension rates with no differences by sex. [44]

In this study, prevalence of obesity is higher than overweight, contrary to most researchers’ findings and in contrast to a national Cuban study (which found 30.8% overweight and 11.8% obesity),[22] but consistent with those of Pérez[45] in Puerto Rico and Rodríguez[46] in Spain, who found higher rates for obesity.

Knowing community-level prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors enables assessment of its magnitude serves as evidence for more effective resource allocation. This is crucial in countries such as Cuba that provide free delivery of health care in a public system with universal access and coverage.

Moreover, although metabolic syndrome is itself consi-dered a multiplex risk factor,[4] it would be useful to measure prevalence of risk factors for metabolic syndrome, to be able to go further upstream in the prevention chain. This study did not attempt to measure such common risk factors as sedentary lifestyle, alcohol consumption and dietary habits, a study limitation.

Research on these factors is recommended. However, this study is the broadest to date on prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors in Holguín Province, as a first step for design and implementation of intervention strategies based primarily on lifestyle changes in the affected population.

Prevalence, of course, cannot be used as a risk surrogate, because it is affected by survival rates. Period prevalence for longer periods (≥10 years) is used internationally in chronic disease surveillance as an indicator of population burden,[47] although, as noted by Ward, may not reflect current population status.[48] Our lengthy data collection period may mean the period prevalence observed does not precisely reflect current population burden.

Nevertheless, this study provides an indication of the magnitude of metabolic syndrome as a public health problem in Holguín Province. Few studies using representative samples have been published on metabolic syndrome risk factor prevalence in the province, representing a disadvantage when judging this study’s external validity, but an advantage when considering the data gap it fills for clinical and epidemiological characterization of these conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

High prevalence of metabolic syndrome risk factors confirms the magnitude of this public health problem in Holguín Province, Cuba.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the managers and workers in the study health areas and at the Medical University of Holguín.