These statements indicate that these participants managed to grow in the face of difficulties they encountered from changes in their personal lives as students and in the general social context. While they spent more time living at home or in the student residence with no face-to-face therapeutic support, they nevertheless were able to overcome stress-induced consumption temptations, retaining some of the progress achieved during their earlier face-to-face therapy sessions. They also adequately addressed challenges posed by the unexpected switch to remote therapy modalities.

Difficulties in dealing with specific events and situations Despite the aforementioned coping mechanisms and strategies, the greatest danger to each patient’s continued recovery lay in having to face specific events and situations that exceeded their personal resources. Such difficulties were experienced by 25 participants (67.5%), as stated in interviews. For example, some expressed doubt as to the need for some of the guidelines issued by health authorities. Although they accepted the necessity of hygienic measures and specialized care for infected patients, they questioned preventive social isolation and the suspension of face-to-face classes and alternative care activities such as psychotherapy and self-help groups.

Other statements reflected participant uncertainty about the efficacy of COVID-19 treatments, expressing critical views of some of the indicated therapies, opinions that relied on sources other than health authorities or healthcare providers. It was also evident that several participants were struggling with time management in their daily lives. ‘Time management’, for our purposes, is the particular way in which individuals organize their daily activities and implies setting aside time for study, work, family and relationships, childcare, hobbies, rest and relaxation, etc. They said that staying at home or in student residences forced them to give up their usual physical and recreational activities, and some students made little effort to resume these activities.

Some participants referred to the emergence or re-emergence of family or group disagreements. This disruption is common within families of addicts and required negotiating complications like renewed consumption or other situations that are caused or aggravated by social isolation. Likewise, other participants reported difficulties in accepting isolation from family and friends with whom they weren’t living. This was a frequent comment among students whose families were either living abroad or in other Cuban provinces.

Participants also described alterations in their sleep–wake cycles generated by the changing circumstances. This was especially evident among students who did not elect to participate in research activities, for whatever reason. Additionally, students expressed worry about the inaccessibility of other sources of complementary professional help, such as psychotherapy and self-help groups (alcoholics anonymous, narcotics anonymous, etc.).

Perpetuation of myths related to drugs and addictive activities These were referred to in 19 participant interviews (51.3% ). Such misconceptions increase the likelihood of succumbing to addictive temptations by attributing beneficial qualities to psychoactive substances and addictive behaviors—among these, greater ability to avoid adversity, generate enjoyment and strengthen sociability. The myths relayed in patient interviews referred mainly to use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana and social networks.

Myths about tobacco. This is a drug with considerable addictive power that can lead to addiction shortly after initiating use. Tobacco’s main component, nicotine, is a stimulant. The idea that tobacco is capable of generating peace or relaxation, much less that it conveys a sense of maturity or responsibility, has no basis in fact. Drugs that are smoked also produce damage to the respiratory tract, which can put users at a greater risk for developing severe forms of COVID-19.[24]

Participants expressed misguided ideas about tobacco, even if they did not habitually use the drug. For example, one participant said they had thought they might begin smoking cigarettes to decrease tension, as doing so during quarantine wouldn’t result in addiction. Others said smoking during isolation would generate peace and help them relax, and some of the younger participants thought that it might make them look more mature and responsible. A few mid-level students in the allied health professions commented that since the novel coronavirus cannot survive high temperatures, smoking drugs like tobacco and marijuana might contribute to its control. These myths, gathered from participant interviews, could contribute to setbacks and addiction relapses.

Myths about alcohol. Alcohol is a depressant whose consumption in excess can generate or exacerbate problems in work and study, as well with family and other social relationships. Low alcohol concentration per drink does not lessen addictive potential, as any alcoholic beverage consumed in large quantities is capable of generating an addictive response. Alcohol’s unquestionable utility in external disinfection does not mean that its consumption constitutes a preventive measure against disease.

Most of the false notions about alcohol expressed in interviews came from participants in therapy for other addictive substances or activities, who believed that alcohol is not a drug and that its consumption helps relaxation. Some participants also stated that beer and wine are not capable of generating addiction, that they are healthy lifestyle choices and useful during social isolation. Some younger students expressed that since alcohol is being used to curtail transmission by using it to disinfect hands and surfaces, then its consumption can destroy the virus in the body. These myths, if acted upon, can result in difficulty controlling alcohol misuse and may even contribute to novel addictions.

Myths about marijuana. Like any other psychoactive substance, marijuana has the potential for medicinal use, but the idea that marijuana is beneficial for health simply because it is ‘natural’ has no basis in fact. Like tobacco, it can result in respiratory difficulties and can contribute to severe manifestations of COVID-19.[25] Likewise, marijuana does not enhance learning abilities or the assimilation of information; on the contrary, it can have a negative effect on motivation for studying or for self-care.[26]

Some participants expressed beliefs that over-estimated the medicinal benefits of marijuana. They also described it as a ‘natural product’ whose use is thus beneficial to people’s health. Several stated that during preventive social isolation, people in higher education may benefit from marijuana, as its use stimulates learning abilities. A Latin American participant argued that the use of natural medicines containing marijuana is a common practice in his country and that it is beneficial for relieving tension and anxiety symptoms. While we recognize cannabis’ medicinal benefits, people who smoke or ‘vape’ (either tobacco or marijuana) are at elevated risk of severe COVID-19.[25]

Myths about social networks. Social media facilitates information sharing, but indiscriminate use can generate addiction and other problems. During disasters and emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, social media can become a source of confusion and stress if all information is assumed to be factual or objective. Rumors can spread through social networks and can negatively affect people’s health and well-being. Spending inordinate blocks of time on social media, including online games, can also be harmful.[27]

Themes related to the indiscriminate use of social networks and techno-addictions in general emerged during analysis. These myths were described by patients currently undergoing treatment for addiction to chemical substances who had also engaged in excessive social media use during the pandemic, often searching for information about COVID-19 in a compulsive manner. One participant stated that social networks are secure sources of information which only disseminate truthful news; another argued that in order to stay up-to-date regarding the pandemic, one must be aware of the rumors that are constantly generated about the SARS-CoV-2 virus. These notions can lead to indiscriminate acceptance of all manner of unsubstantiated claims made in social media, and to obsessive behaviors. In the case of social media addicts, myths prevailed regarding the habitual use of social networking activities, like the idea that regular participation in online games is a non-dangerous practice that makes social isolation more acceptable.

Irrational tendencies and lack of emotional control Of the 37 participants, 16 (43.2%) expressed difficulty in controlling their emotions in conditions of preventive social isolation. They added that they often engaged in compulsive behaviors. Several participants referred to higher incidences of negative emotions like fear, sadness and anger. One participant commented that in their current circumstances, fear constitutes a frequent and unpleasant emotion, which led to feelings of immobilization, anxiety, panic and insecurity. The constant concerns surrounding not only the very real possibility of getting sick, but also the possibility of infecting family and friends, caused distress and led to feelings of melancholy and depression.

Emotional dysregulation is common during rehabilitation and social integration processes, manifesting with greater intensity during critical or difficult situations. Some participants spoke of frequent and sometimes uncontrollable anger, which was sometimes linked to feelings of resentment toward others. Additionally, several participants from outside Cuba noted that they were very affected by not knowing the current situations of their relatives, which caused them serious worry, leading to a tendency towards feelings of immobilization while waiting for news. One participant expressed frustration and sadness at what was perceived as the unfair fact that reality fails to coincide with one’s desires. Many students described negative emotions associated with the belief that it is unacceptable to not be competent and successful in all circumstances one happens to encounter. However, most patients navigated these difficulties without experiencing setbacks in their recovery.

LESSONS LEARNED

Narrative designs are especially useful in social and health sciences, as they encompass attempts to understand the succession of facts, situations, phenomena, processes and events involving thoughts, feelings, emotions and interactions related by the people who experienced them.[28] Participants’ statements made it possible to verify that most of them had developed coping strategies for maintaining self-control, which facilitated addressing and overcoming addictive temptations. Their treatment prior to suspension of face-to-face therapy sessions contributed to these strategies, exposing and reinforcing the incongruities of consumption and other addictive practices with the process of their professional training and their lifelong goals. The above arguments and adherence to treatment, fostered in part by commitment to their therapists, facilitated consistent positive changes in many of the patients over a short time, which in turn contributed to effective psychological coping mechanisms, allowing them to face unexpected difficulties imposed by the pandemic without setbacks or relapses.

During circumstances such as social isolation, the risks of initiating, continuing or re-initiating drug use can manifest in various ways. This depends largely on substance type or specific activities and how much treatment each individual patient has already undergone.[29] This last aspect could explain how these patients were able to face the stressful circumstances experienced: that is, they were in an intermediate stage of treatment characterized by partial progress in their rehabilitation, and already possessed a foundational understanding and an appreciation of the negative impacts consumption had on their professional training, their life goals and their interactions with their psychologists.

Participants raised doubts about the need to stop academic activities and treatments not considered to be medical emergencies. Compliance with health authorities’ instructions related to social isolation and distancing as well as hygiene minimizes risk of becoming ill with COVID-19. If patients trust that complying with established guidelines will result in greater probabilities of success, they are more likely to adhere to those guidelines.[30] The background literature consulted underscores that success in COVID-19 prevention and management depends on people’s behavior and on changes in their usual lifestyle.[31]

The rational use of time has been proposed as a preventive measure against risky behaviors like drug and alcohol abuse, as has attempting to maintain routines as much as possible.[32] During preventive social isolation, perception of time is altered; people often have the impression that days and nights are extremely long, they tend to be more inactive, and they sleep excessively.[33] Their normal routines disrupted, participants often failed to take into account that various activities can be done at home, including individual study, preventive actions within their residential communities and other forms of individual work or collaborative telework.

Living together in limited space can generate or exacerbate disagreements among family members or cohabiting individuals. In this case, appropriate negotiations aimed at fostering an atmosphere of understanding that facilitates continued abstinence should be promoted. One guide for psychological management of confinement during the COVID-19 crisis[34] insists these steps are essential to avoid or ameliorate symptoms of acute stress, exhaustion, irritability and insomnia.

Maintaining connections with family, friends and colleagues with whom one habitually participates in social activities, psychotherapies and self-help groups,[35] and maintaining a ‘normal’ sleep–wake cycle (which can help patients avoid insomnia, fears or even generalized anxiety and panic attacks)[36] are both practices that can help individuals face novel challenges.

SC-CEDRO provides patients with a care regimen based on planned consultations. However, many patients also seek guidance for challenges arising from specific needs and conflicts through psychotherapy and self-help groups. Study participants referred to the potential negative impact of the suspension of these groups during this period.

Tobacco and rum have traditionally been considered part of Cuban culture. Globally, the purported benefits of marijuana have been disseminated through media campaigns aimed at its legalization and decriminalization.[25] Study participants made reference to myths that were exacerbated during social isolation regarding tobacco, alcohol, marijuana and the indiscriminate use of social networks.

Tobacco use generally leads to addiction.[37] Adolescents often correlate smoking with ‘maturity.’ Cigarette smoking can cause high blood pressure and other oncological, cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, which can lead to poor disease progression in persons infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.[38]

Some so-called ‘new myths’ were identified during interviews, which erroneously confer protection against the SARS-CoV-2 virus to certain addictive drugs and practices. The false nature of these claims is especially true in the case of drugs that are smoked, like tobacco and marijuana, as COVID-19 mainly affects the respiratory system. The harmful effects of cigarette smoking include a significant reduction in defenses and a progression towards chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, both risk factors for COVID-19.[39]

Alcohol use can also increase an individual’s vulnerability to COVID-19, as it is associated with negative health effects including but not limited to a weakened immune system and an increased susceptibility to pneumonia and other acute respiratory infections.[40] Irresponsible alcohol use can lead to a lack of social discipline and a lapse in preventive measures.

WHO has warned that abuse of social media can lead to an increase in anxiety and anguish,[16] which was perceived in our interviews, whether or not participants were addicted to social media. The wave of misinformation available on social networking sites has been called an ‘infodemic’ and is considered a pandemic parallel to COVID-19.[41] In Cuba, ample information is provided daily on COVID-19, as national and global data are published in daily Ministry of Public Health bulletins, and resources are continually updated via national media and internet. Top Cuban health authorities appear daily in media briefings that address ongoing problems generated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and government authorities provide timely public reports on decisions taken in the national pandemic working group, charged with systematic analysis of the ever-evolving situation.[42]

New terms have also emerged in youth slang and popular parlance: a ‘video-drink’ of alcohol with friends, ‘online sex’, or ‘sexting’ as a compulsive practice.[43] A very real risk is the practice of games linked to alcohol consumption, like the one known as ‘Neknomination’, or ‘Neknominate’. This game involves ingesting a large amount of alcohol, taking a video, uploading it to social media and inviting friends or other people to meet the ‘challenge.’[44] Given that patients in this study are young and most have alcohol-related disorders, the rise of such practices constitutes a latent risk.

Lack of emotional control and tendencies toward irrationality were observed in some study participants who had to adapt to different sociocultural environments, most notably living with classmates in student residences while separated from their families. Emotional disorders are common in patients struggling with addiction and are compounded by critical situations like the pandemic. Such situations constitute mental health emergencies.[45] The control of stress-generating compulsive thoughts should be exercised as a prophylactic measure, and attention diverted to rewarding aspects of an individual’s personal, family and community life. SC-CEDRO teletherapy is framed around encouraging patients to plan their days well and exercise responsible coping mechanisms when faced with challenges. Psychological interventions are based on the acceptance that reality is independent of individual will, but individuals can adopt resources allowing them to effectively deal with changes in their situations.[46] This is true for both vulnerable populations and for all those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Controlling negative emotions does not constitute their denial, as they are normal in these kinds of situations.[35] Breathing exercises, relaxation, meditation and other activities have been useful in managing the anxiety caused by news about the novel coronavirus.[47] Fear can be handled positively, enhancing the perception of, and allowing individuals to better recognize, risk; and even sadness can grant individuals enriched inner dialogues and deeper self-knowledge.[48] Refusing to acknowledge these emotions can result in inadequate ability to cope with adversity. Even extremely negative reactions like anger and rage can be vehicles in achieving security, confidence and a sense of firmness. The proper management of these emotions can promote individual assertiveness and help prevent uncritical subjection to outside expectations. These emotions foster young people’s defensive capacities and, when accompanied by self-control, promote the development of self-confidence and self-esteem.[49] Strengthening one’s self-control of emotional states and controlling one’s tendencies toward irrationality are essential.[50]

The importance of this study lies in the fact that at the time it was carried out, there was no research in Cuba that considered possible effects of situations generated by COVID-19 on people with addictions. There was concern within the services that attend to these patients, since rehabilitation requires routine therapeutic monitoring for variable time periods, plus subsequent follow-up appointments. The health emergency posed by COVID-19 prevented these therapies from continuing as planned, which could affect therapeutic adherence and recovery. The results of this study are useful in developing corrective strategies and preventive interventions applicable to this situation and other special circumstances related to disasters or other emergencies.

The main study limitation was the application of a qualitative narrative design through telepsychology. This implied difficulties in obtaining data from visual observation and extra-verbal communication. Even after interviews were conducted, coded and interpreted by several researchers independently and then reconciled among all researchers, it was not possible to rule out alternative interpretations. Such a case would be less likely with the use of other resources or with face-to-face interviews.

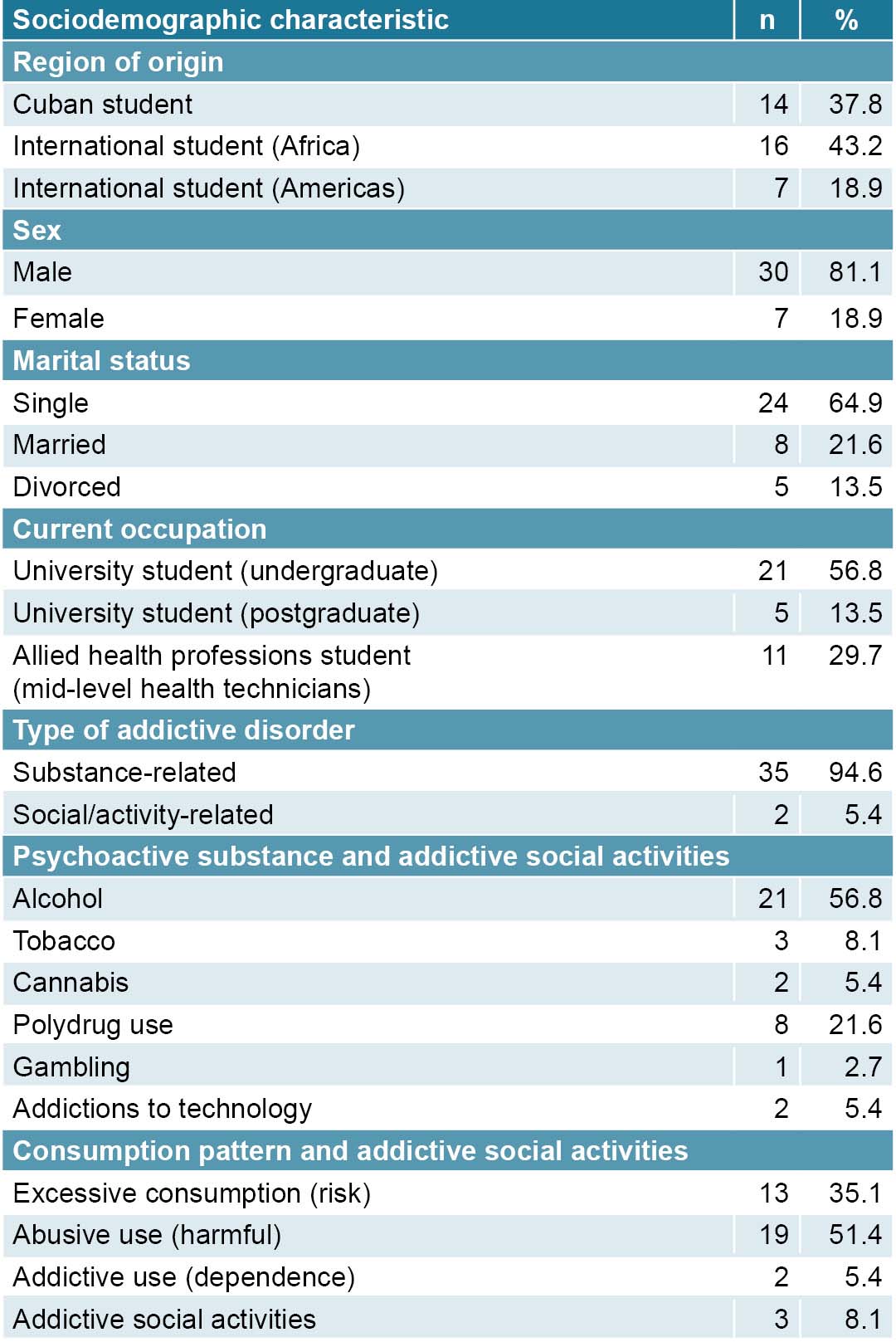

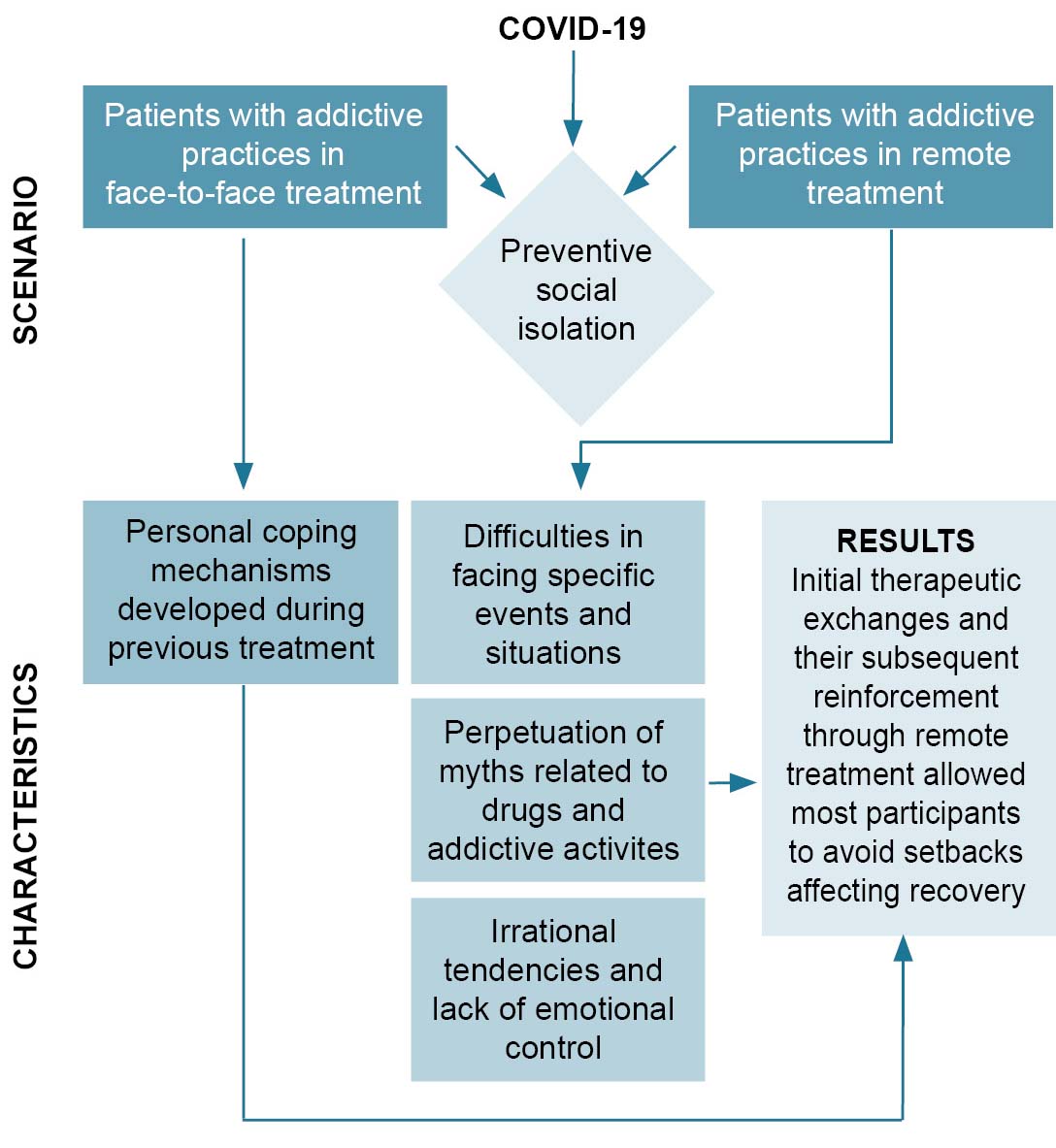

This study identified the characteristics of psychological coping mechanisms present before the COVID-19 pandemic in a group of people with disorders related to psychoactive substances and other addictions. Our findings suggest that despite the negative effects of the pandemic, the personal goals and mechanisms for self-control developed by participants during prior therapeutic exchanges and subsequent treatment conducted through telepsychology allowed many patients to face new and unexpected difficulties without compromising their recovery. We also identified circumstances favoring potential relapse, including difficulties in addressing specific events and situations, perpetuation of myths related to drug use and other addictive activities, and a tendency toward irrationality and lack of emotional control.