“I had ten brothers and sisters. We were so poor,” relates Algimiro Ortíz in the honeyed afternoon light flooding the Seniors’ Center in Cruce de los Baños. “School wasn’t an option—there wasn’t a school here—only work; I began picking coffee when I was 11. When somebody got sick, we had to carry them on our shoulders to the hospital in Contramaestre, 16 miles away,” Ortíz, now in his 70s, told MEDICC Review.

Ortiz’s story is representative of pre-1959 life in this remote rural town nestled in the Sierra Maestra—Cuba’s highest mountain range. Typified by large families coping under the triple burden of poverty, illiteracy and malnutrition, rural populations like this one were among the country’s most vulnerable and forsaken over half a century ago.

At that time, Cuba had only one rural hospital, 80% of children had intestinal parasites (the number one cause of death nationally) and 60% of the population was undernourished.[1,2] Life expectancy in rural regions was 50 years and infant mortality was 100 per 1000 live births.[3] Social determinants affecting health were equally dismal: a survey by the University Catholic Association conducted between 1956 and 1957 in a representative sample of 1000 rural families found that only 6% of homes had indoor plumbing, 64% had no latrine and 83% had no bathing facilities. Only 11.2% of farmworker families drank milk; likewise, only 2% were eating eggs.[4] Making matters worse, nearly 42% of rural people could not read or write.[5]

The precariousness of life in the Sierra Maestra and other remote areas was not lost on Fidel Castro and the rebel forces, who depended on logistical and material support from rural communities throughout the years of their fight against the Fulgencio Batista regime. Trudging over the same rugged, unforgiving terrain plowed by these subsistence farmers and landless peasants, sleeping in their homes, and sharing food, stories and similar pathologies, underscored the fragility of life for Cuba’s rural poor. The need for integrated social development policies was obvious.

One result, even before the war was over, was the establishment of a series of rural hospitals and medical posts deep in the Sierra Maestra to treat the wounded (rebel and enemy), and expressly to provide basic medical and dental care to surrounding communities.[6] This seminal initiative in rural health was both turning and starting point for a coordinated strategy for health services provision in the country’s most remote areas.

Sowing Seeds of Health

Following Batista’s ouster in 1959, the new government initiated three programs that were to have significant impact on health and its social determinants in the Cuban countryside: the 1959 agrarian reform (giving deeds to 150,000 landless peasant families),[7] the 1961 literacy campaign (which according to UNESCO taught some 700,000 Cubans throughout the country to read and write[8] and the Rural Medical Service (RMS) begun in 1960. The latter was followed by the Rural Dental Service (1961) and the Rural Red Cross (1963). These programs were complemented by educational reform and road improvements in remote areas. Ortíz notes that his family and those of farmers like him learned to read and write at that time; meanwhile, seeking medical care no longer required a 16-mile hike, and parasites and serious infections ceased to mean certain death.

In any health system, remote posts are notoriously hard to fill—and in Cuba’s case, nearly half the country’s total number of 6300 physicians emigrated between 1959 and 1963, complicating the picture.[9] When the University of Havana reopened in 1959 following the war, rural service was hotly debated among medical students. The often tumultuous assemblies struck at the heart of the issue: the right to health care, especially for vulnerable populations. As a result of these discussions, students voted unanimously to volunteer in rural areas for a period upon graduation. Thus, the Rural Medical Service, built into the health system by Law # 723 of 1960, was born. Health authorities created posts for the newly graduated MDs, and in March 1960, the first group of 357 volunteers arrived in the countryside.[10]

Challenges faced by the Rural Medical Service, c. 1960. / Granma Archives

The population health approach that came to define the Cuban health system after 1959 was rooted in the RMS: the Service’s guidelines reflected national priorities to make health services universally accessible, prevent disease and provide population health education. As a result, vaccination campaigns were launched, as well as other programs, such as one to combat gastroenteritis, and reporting became mandatory for certain infectious diseases. By 1970, the total number of rural hospitals had reached 53, and by 1971 the proportion of doctors practicing in the capital city was estimated at 42%, compared to 65% in 1958.[6,11] In his 1976 assessment for PAHO of Cuban health services and resources, UCLA’s Dr Milton Roemer concluded: “The greater equity achieved in distribution of health resources, as between urban and rural areas, has been one of the most impressive results [since 1959].”[11]

To complement the RMS and address human resource shortages, provincial medical schools were established[12] with a social accountability component that required doctors to serve in rural settings for a year following graduation. This commitment was subsequently extended to two years in a national social service program for all graduates, most serving closer to home. But those at the top of their class are still posted to the most remote and precarious areas, including the Sierra Maestra mountains.

Fast forward a few decades and Cuba’s human and capital investment in rural health was paying dividends in longer life expectancy; a dramatic drop in maternal and infant mortality; and a shift in disease burden away from preventable communicable diseases—including parasites and diarrheas—towards chronic noncommunicable conditions. In short, the health picture in these remote, once forsaken areas was beginning to resemble that of the rest of the country. But as health evolved, so too did the Cuban approach.

Tilling & Tending Fertile Ground

In 1984, the Family Doctor Program was launched, aligned with tenets laid out in the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration, which stated health as a right and primary health care as the primordial strategy for fulfilling that right.[13] Family doctor and nurse teams were located in neighborhoods across the country—from the city to the mountains, from the swamplands to the coast—where each cared for between 120 and 160 families and reported to a community-based polyclinic. In a major shift, medical graduates were required to complete a residency in family medicine before choosing a second specialty.

These teams supplanted the community polyclinic as the health facilities closest to people’s homes in both rural and urban settings, representing a sea change for primary care in Cuba. Having health professionals living and working in each neighborhood facilitated prevention and promotion activities, epidemiological surveillance, and more attention to lifestyles, environmental factors, housing conditions and other social determinants affecting health. Yet, in the rural and remote areas in particular, it became clear that to continue improving population health, a more comprehensive intersectoral approach was needed.

Over 700,000 people—approximately 6% of the country’s total population—live in Cuba’s most remote and mountainous areas.[14] These communities are far flung, but tightly knit; vulnerable, yet resilient. Here, interdependency, working with your neighbors to solve problems, and pooling resources and knowledge to affect change are a way of life. In order to systematize this knowledge and provide support for sustainable, comprehensive development of these regions, the PlanTurquino-Manatí was launched in 1987.

Covering 50 remote municipalities across the country, the Plan uses a decentralized, coordinated approach to improve production and promote economic efficiency, protect local ecosystems, and foster food security and population health. The stated goal is to provide the necessary support for these regions to advance economically and socially, independent from urban centers (with the aim of stemming brain drain to the cities) using contextually-appropriate strategies. Health services for example, incorporate natural and alternative medicine, traditionally used for health maintenance and improvement in rural areas.

The key to achieving the program’s goals was to foster cooperation among various sectors to improve social determinants at the local level—what WHO and others have termed ‘health in all policies.’ Easier said than done, says Dr Pastor Castell-Florit, director of Cuba’s National School of Public Health (ENSAP, the Spanish acronym). He notes that in the health field alone, effective coordination of this sort requires political will, public awareness and organization, highly trained human resources, multidisciplinary health sciences curricula and universal access to health care. Although these factors were in place in Cuba by the end of the 1990s, ten years after the Plan Turquino-Manatí had gone into effect, intersectoral efforts had stalled.[15]

In response, the National Plan Turquino Commission was formed in 1997 to coordinate among sectors and ministriesincluding health, education, culture, and agriculturecomplemented by new provincial and municipal commissions charged with local-level cooperation; a 260-point program was developed to carry out the strategy. Sports fields and housing, post offices and radio transmitters were constructed; libraries and cultural centers were established; the electrical grid, potable water sources, and telephone services were expanded; and a consortium of 29 scientific institutions carried out knowledge and technology transfer (specifically addressing agricultural yields).[16]

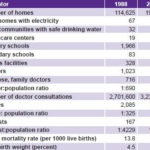

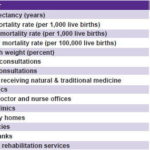

Selected Outcomes of Rural Cuba’s Plan Turquino, 1988–2003

Source: Programa de desarrollo integral de la montaña. Plan Turquino Manatí, 17 años de avances.

Case Study: Cruce de los Baños

Today, the cumulative efforts of the Rural Medical Service, the Family Doctor program and Plan Turquino are showing results in the small mountain town of Cruce de los Baños in Santiago de Cuba province’s Tercer Frente municipality. The demographics and health picture here are similar to the rest of the country, with adults 60 and older comprising 16% of the population, the single largest group in this health area served by the local polyclinic (one of two in the municipality). Chronic diseases—specifically cancer, but also hypertension and high cholesterol—represent the number one causes of death.

Snapshot: Tercer Frente Municipality, 2010-2011

Source: Municipal Health Department, Tercer Frente, Santiago de Cuba province, Cuba.

But Plan Turquino towns also present unique health challenges including water-borne diseases and those specific to the agricultural sector.[17] For instance, leptospirosis, a disease contracted through contaminated water, soil or animals is a pressing health problem in these areas, as are intestinal parasites.[18]

The case of leptospirosis offers an example of the coordinated approach: a national vaccination program for those at high risk (including most people over age 15 in the Cruce de los Baños health area) is coupled with health promotion efforts and a Red Cross clean water program to control and prevent the disease. The Red Cross program also contributes to curbing water-borne diseases through public service announcements, community activities, and brochures that describe safe water sources, how to treat unsafe water and why this is important for good health.

National programs prioritizing vulnerable groups are also instrumental in maintaining health in Cruce de los Baños. For example, maternal and child health—historically undermined by high mortality and morbidity in these areas—has improved in large part due to the National Maternal-Child Health Program (PAMI, the Spanish acronym). Through this program, women receive full intake exams by the ninth week of pregnancy, followed by at least 12 antenatal visits and standard screenings, including ultrasound. The continuum of care once the baby is born includes immunization against 13 childhood diseases and regular follow-up visits for mother and child. High risk pregnancies receive individualized care at the local maternity home and attention through consultation with specialists, including pediatric cardiologists and geneticists.[19]

“Health improvement is supported by bringing care closer to those needing it: Our doctors regularly go into the field to visit patients who can’t travel to the polyclinic and this has been especially important in maternal and child health,” Dr Julio César Luis Félix, Director of the Cruce de los Baños Polyclinic told MEDICC Review on a recent visit. “Indeed, this health area has registered zero maternal deaths over the last 20 years.”[18]

Dr Félix also noted that his polyclinic, which serves the over 18,000 people in this health area, offers some 20 services, using the same technology as those in urban settings.

Intersectoral work is a key piece of the quality-of-life puzzle and is coordinated via monthly meetings of the local Health Council, a group that includes representatives from culture, the small farmers association (ANAP, its Spanish acronym), the local Maternal-Child Health program, the polyclinic itself and others. In these meetings, strategy and progress are discussed, problems identified, and solutions presented and debated.

C Gorry

Mother and her infant at a well-baby visit, Cruce de los Baños Polyclinic. / C Gorry

Services at Cruce de los Baños Polyclinic Tercer Frente Municipality, Santiago de Cuba Province

Source: Personal communication, Dr Julio César Luis Félix, Jan 5, 2012.

Nevertheless, there is still work to be done. According to Dr Félix, anemic and undernourished expectant mothers account for the largest group of high-risk pregnancies in Cruce de los Baños, followed by teenagers, who account for 20% of expectant mothers in the Tercer Frente municipality (which includes Cruce de los Baños and Matías’ health areas).[18] Municipal health authorities emphasize that most of these teen mothers are between 17 and 19. They are designing mechanisms to lower the numbers of teen pregnancies by working with the community and other sectors. For example, family planning services offered at the polyclinic are complemented by prevention messages shared with the community by neighborhood associations and the local chapter of the Cuban Women’s Federation. Prevention work is supplemented by the Multidisciplinary Health Education Team which brings health promotion messages to the community through radio broadcasts and door-to-door visits.

Older adults are another vulnerable group in Cruce de los Baños. Under the auspices of the national Comprehensive Older Adult Program, the polyclinic’s Multidisciplinary Gerontological Care Team (EMAG, its Spanish acronym) takes the lead in community-based attention to elders. This multidisciplinary group is comprised of a family doctor, nurse, psychologist and social worker—all with specialist geriatric training—who provide regular medical checkups, coordinate specialist referrals and appointments as needed, and assess the overall health and wellbeing of the area’s older adults. The Team also makes weekly visits to the Seniors’ Day Care Center in Cruce de los Baños, which has a full-time nurse on staff.

Older adults at the Seniors’ Center, Cruce de los Baños. / C Gorry

Cruce de los Baños, 2011. / C Gorry

There are more than 230 of these centers for older adults around the country, where members spend their time gardening, playing games, taking exercise and other classes, participating in community activities, singing, dancing, conversing and eating. In the countryside, these centers serve as nutritional safety nets: each member is provided three meals and two snacks on a typical day. Indeed, after the camaraderie and engaging activities, it was the food that excited Cruce de los Baños elders most. “The food is so good!” exclaimed one senior during MEDICC Review’s visit. “Sometimes it’s even better than at home, where we don’t always have the resources they have here.”

Medical education remains instrumental in improving population health in rural areas including Cruce de los Baños. “Before, health professionals serving in this area came from Santiago de Cuba or elsewhere, but now, all the young people working here were born here. They feel a responsibility to our community; they feel like they belong,” said Dr Félix. The first doctors and dentists from the area began training here in 2005; currently 164 students train at this polyclinic to become doctors, nurses, dentists and health technicians. Familiar with the context and health problems particular to remote populations, these young health professionals represent the future of primary care in the Sierra Maestra.

Promoting health and providing the necessary services to maintain the health and wellbeing of those living in remote areas is an ongoing process, however, and challenges remain. For example, transporting patients over the rugged, steep and, in many cases, still treacherous roads is a perennial problem. Specially outfitted ambulances with four-wheel drive are a partial solution, as is ongoing road improvement, but maintenance of those ambulances and roads requires increasingly scarce resources. Distance and access to health facilities in these areas cannot be measured simply in miles, but according to “real accessibility which can be a decisive factor given the limitations of public transportation and the [high] price of private transport” for rural families.[20] In light of these realities, it is encouraging to see that very few health facilities have been closed in the Tercer Frente as the consolidation of health services that began across the country in 2010 continues apace. However, maintaining accessibility will need careful monitoring moving forward.

Conclusions

The health of rural populations in Cuba today can be traced back to concepts and strategies developed half a century ago and the subsequent high priority given to improving social determinants of health, particularly for vulnerable populations. Since the founding of the RMS in 1960, the approach to rural health has remained consistent in Cuba, with periodic innovations in response to the changing health picture. Such flexibility and capacity to evolve should be further studied and encouraged. Moreover, rural communities have shown a sustained capacity for working across sectors to improve health, an experience that could be adapted to other areas in the country where such coordination and cooperation have faltered. Although resource scarcity often limits what is practical in the Cuban context and certain goals like a world class road system may be out of reach for some time, the experience in rural health over the past 50 years in the Cuban mountains and countryside has shown that remote location, lack of resources and other unfavorable variables are not insurmountable barriers to better health.

References

- De la Torre E, López C, Márquez M, Gutiérrez JA, Rojas Ochoa F. Salud para todos: Sí es posible. Havana: Sociedad Cubana de Salud Pública (CU); 2004. Spanish.

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Report on Cuba. Findings and recommendations of a technical mission (“Informe Truslow”). Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press; 1951.

- Interview with Dorisbel Ramos, Lead Specialist, Tercer Frente Historical Complex, 12 Dec 2011.

- Agrupación Católica Universitaria. Encuesta de los trabajadores rurales 1956-1957. In: Economía y Desarrollo. 1972 Jul-Aug;12:198.

- Jeffries C. Illiteracy: A World Problem. London: Pall Mall Press; 1967.

- Delgado García G. El Servicio Médico Rural en Cuba: Antecedentes y Desarrollo Histórico. In: Cuadernos de la Historia de la Salud Pública No. 72. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 1987.

- Labrada E. Reforma Agraria en Cuba: la otra historia. Periódico Adelante (Camagüey). 2011 May 17. Spanish.

- Cuba’s Literacy Campaign was led by more than 160,000 (mostly) young people and teachers who volunteered to go into the countryside to teach the illiterate rural peasantry to read and write. As a result of these efforts, Cuba was declared illiteracy-free by UNESCO in 1962 (the first country in Latin America to be thus recognized). It is interesting to note that the Cuban approach emphasizing the effects education, land use, housing, road access, and other factors have on health predates the global understanding of social and environmental influences on health first described in the 1974 Lalonde Report in Canada.

- Navarro V. Health, health services and health planning in Cuba. Int J of Health Services. 1972 Aug;2(3):413.

- Rodríguez Rivera A. En el hocico del caimán. Havana: Ediciones Unión; 2007. Spanish.

- Roemer MI. Cuban Health Services and Resources. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 1976.

- In 1959, there was one medical university in Cuba; today there are 14 (13 provincial and the Latin American Medical School).

- Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1978 [cited 2011 Jan 15]. 3 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf

- FAO. Plan Turquino: Strengthening the Programme for Comprehensive Development of Cuban Mountains. c 2003 [cited 2011 Dec 22]. Available from: www.fao.org/forestry/forestsandwater/59080/en/

- Castell-Florit P. La intersectorialidad en la práctica social. Havana: Editorial Ciencias Médicas; 2007. Spanish.

- Gandul L, Luna EC, Sierra DC. Programa de desarrollo integral de la montaña. Plan Turquino Manatí, 17 años de avances [Internet]. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr. 2008 Jun [cited 2011 Dec 22];25(2). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/mgi/v25n2/mgi12209.pdf. Spanish.

- Interview with Dr Pablo Reyes, Municipal Health Director, Tercer Frente, 2011 Dec 12.

- Interview with Dr Julio César Luis Félix, Director, Cruce de los Baños Polyclinic, 2011 Dec 12.

- For a full discussion of Cuba’s maternity home program, see Cuban Maternity Homes: A Model to Address At-Risk Pregnancy in MEDICC Review. 2011 July;13(3):12–5.

- Iñiguez L. Aproximación a la evolución de los cambios en los servicios de salud en Cuba. Rev Cub de Salud Pública. 2012 Ene–Mar;38(1). Spanish.