Excerpted by the author, translated and reprinted with permission from Novedades en Población. 2013 Jul–Dec;18:55–68 Original available at: http://www.novpob.uh.cu/index.php/rnp/article/view/43

ABSTRACT

The article examines the effects of immigration on the population dynamics of a traditional immigrant-recipient country, Canada. Data from the 2011 Canadian census suggest that Canadian population growth, as well as the stability of the economically active and reproductive-age population, largely depends on the steady arrival of new immigrants. Management of immigration flows to suit [domestic] development needs is therefore an essential component of Canadian policy regulating entry of new permanent residents. The Cuban immigration case study illustrates how Canadian migration regulations influence the sociodemographic features of a specific group of immigrants and the impact that such movements may have on the development of traditional countries of emigration, such as Cuba, because of the loss of human potential.

KEYWORDS: Population dynamics, census, immigration policy, migration policy, Canada, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

Immigration plays an essential role in population dynamics worldwide. How it affects a particular country, however, is closely related to each country’s immigration tradition. Immigration, especially of working-age immigrants, can contribute significantly to population growth in destination countries, whereas for countries of origin it often entails a serious drain of human potential.

. . . Promoting entry of new immigrants has been a primary concern for Canada, regardless of the political party in office. Canada’s traditional immigration policy, as stated in the Immigration Act of 1910, was based on a consistent philosophy that immigration flows should make a special contribution to achieving the country’s social and economic objectives. This approach was recently revised by the government agency Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), which stated that immigration’s primary aim is to respond promptly to labor market pressures and employer needs while helping maintain a flexible and competitive workforce.1 . . .

Because of its high social development, Canada has long been one of the most attractive destinations for immigrants from around the world. It is regularly among those with the highest annual human development . . . and its dynamic economy provides employment opportunities for new arrivals.2

Results of the 2011 census clearly showed the growing importance of immigration flows as a key element in Canada’s current population growth. However, this feature is not new. For more than three decades, the country’s natural increase has been dropping, making immigration the main growth driver reported in recent census periods. Canada’s current population dynamic is heavily dependent on new immigration flows.

Thus entry of new immigrants becomes a strategic issue for Canada . . . However, not all immigration is welcome. In maintaining a selective policy on permanent residency for more than 100 years, Canada has been able to attain both objectives: it successfully attracts immigrants who are young but also highly skilled and experienced in their respective professions, as will be seen below.

The case study of Cuba-to-Canada migration clearly illustrates the foregoing. As will be seen in the second section of this paper, there has been a documented presence of Cubans permanently residing in Canada since the mid 1970s, although this group gained greater visibility after the mid 1990s. From the beginning, a constant feature of Cuban immigration to Canada has been the presence of relatively younger and well-educated immigrants, especially in the technical sciences.

A comprehensive analysis considers the effect of departing immigration flows on countries of origin, particularly concerning their real development potential. This assumption takes on greater importance in light of the fact that skilled individuals can obtain temporary immigration status in 92% of developing and 100% of developed countries; approximately 62% of developing countries and 93% of developed countries offer permanent residency to such qualified immigrants. At the same time, in some 38% of developing countries and 50% of developed countries, unskilled workers are not allowed to apply for permanent residency.3 This suggests that Canada, despite its long tradition in selecting new immigrants (especially highly skilled individuals), is not an isolated case but exemplifies a global practice.

IMMIGRATION AND POPULATION IN CANADA: A DEPENDENT RELATIONSHIP

Canada—like the United States, Australia and New Zealand—is traditionally a country of immigrants. As a result of their colonial history, these countries have a long tradition of accepting immigrants (who, in turn, have played a key role in their formation as nations), a practice that continues to the present. These countries also participate in the current international division of labor, and immigration is a vital factor in maintaining their economies and productivity.4 Canada’s current population5 is a mixture of aboriginal peoples, those introduced with the conquest and colonization of North America, and the waves of immigrants who have come to settle in Canada’s vast territory for several centuries . . .

1. Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC): Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, 2009, p. 5.

2. International Organization for Migration: World Migration Report 2010. The future of migration: building capacities for change.

3. United Nations Development Program: People in motion: who moves when, where and why. Human Development Report 2009.

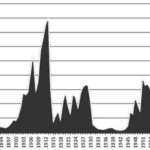

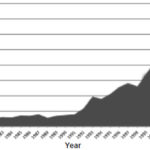

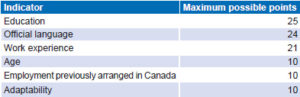

. . . According to expert Sandra Harder, the steady influx of new immigrants into Canada over the last 160 years has played a decisive role in the country’s population growth.6 Close analysis of Canada’s population dynamics reveals that only twice in its history has population growth been based exclusively on natural increase. The first occurred from 1861 to 1901, coinciding with the period known as the Long Depression,7 when many residents of eastern Canada resettled in the eastern part of the United States, attracted by its thriving industrial sector (Figure 1) . . . The second occurred during the period in world history known as the Great Depression (1931 to 1941). In those ten years, annual influx of immigrants dropped significantly from 123,000 in the 1920s to 16,000. Fertility rates, in turn, dropped to their lowest figures recorded up to that time (fewer than three children per woman). However, this was enough to sustain the country’s positive population growth rate (albeit at lower rates than those previously registered).8

The two periods of highest population growth occurred in the early 1900s and the two decades immediately following World War II, the result of a combination of high fertility and immigration rates. From 1901 to 1911, more than 1.2 million immigrants entered Canada, attracted by the newly approved Land Act,9 which aimed to stimulate settlement in the extensive Canadian west. There was also a high fertility rate, with an average of five children per woman.

Figure 1: Total immigrants to Canada (1852–2011)

Source: Prepared by author with data from Citizenship and Immigration Statistics (1966–1996) and Citizenship and Immigration Canada Facts and Figures (2002, 2003, 2008 and 2010).

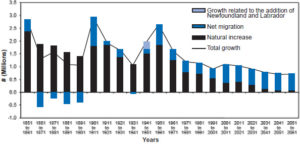

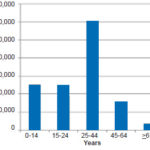

The period from 1941 to 1961 is known as the baby boom . . . Although fertility rates did not attain the same levels as in the early 1900s, the average rate of 3.9 children per woman in the 1950s, along with the equally high immigration rate, enabled this phase to be one of the most dynamic in Canada’s population growth (Figure 2)10.

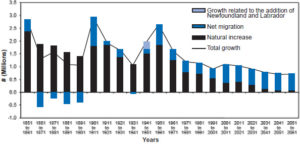

Starting in the 1970s, natural increase began to drop markedly as a proportion of overall population growth; currently, it accounts for only one third of the total population growth rate. This shift is due to a lower fertility rate (down to an average of 1.5 to 1.8 children per woman), a range that has held steady to the present. The Canadian population has also begun to experience a significant increase in number of deaths, as cohorts born in the high fertility periods have begun to reach advanced ages.11

The numbers of births and deaths have converged, making the immigration rate the primary contributor to population growth. Some experts suggest that by 2061, Canada’s population growth could depend exclusively on influx of new immigrants . . . This assumption is reinforced by Statistics Canada projections estimating that by 2031 immigration will account for 80% of population growth, significantly higher than the current 67%. These estimates have led some specialists to predict that, without a sustained level of immigration, Canada’s population growth could be close to zero by the 2020s. . . .

Moreover, immigration is considered by many to be one of Canada’s social strengths. Owing to the country’s historical and social development and the interaction of different coexisting cultures, Canada is considered a multicultural country, a concept that has become embedded in Canadian ideological discourse. In the words of Adrienne Clarkson, Canada’s Governor General from 1999 to 2005:

[As John Ralston Saul has written,] it is a strength and not a weakness that we are a “permanently incomplete experience built on a triangular foundation—aboriginal, francophone and anglophone.” What we continue to create, today, began 450 years ago as a political project, when the French first met the aboriginal people. It is an old experiment, complex and, in worldly terms, largely successful. Stumbling through darkness and racing through light, we have persisted in the creation of a Canadian civilization.12

4. Maria Elena Álvarez: Siglo XX: migraciones humanas, pp. 79-80.

5. Canada (9,984,670 km2) is the second largest country in the world. Its primary natural resources include iron, nickel, copper, gold, lead, diamonds, silver, fishing resources, mineral carbon, petroleum, natural gas and hydroelectric potential. Some 4.57% of all land is arable and approximately 0.65% is permanently planted with crops.

6. Sandra Harder: Accounting for Demographic Change in Migration Policy, p. 3.

7. The Long Depression began in 1873 and lasted until 1879. It is considered to be the first major global crisis in the history of capitalism and marks the end of capitalism’s initial phase, characterized by the prevalence of small businesses, open competition and the construction of national capitals. Resolution of this crisis is tied to expansion of capitalist production experienced in the last decades of the 19th century, as part of its new phases of imperialism and colonization.

8. Laurent Martel y Jonathan Chagnon: Population growth in Canada: From 1851 to 2061, p. 4.

9. The land property law was approved in 1872 and was one of the first policies applied by Canada to stimulate immigration of new inhabitants. Its basic objective was to populate the great extension of lands in western Canada known as The Prairies. The law, which stipulated giving land free in exchange for living on it, attracted approximately 400,000 immigrants in 1913 alone from [continental] Europe, Great Britain and the United States (cf. Nesta Scott: la política de inmigración a Canadá (un triunfo de la inclusión sobre la exclusión), p. 2 and Geneviève Bouchard: op. cit., p. 8).

10. Barry Edmonston: Canadian Provincial Population Growth: Fertility, Migration, and Age Structure Effects.

11. Op cit.; Sandra Harder: Accounting for Demographic Change in Migration Policy.

12. Adrienne Clarkson: Speech from the Throne, 7 October 1999, p. 4.

Figure 2: Population growth observed (1851–2011) and projected (2011–2061), with contributions from natural increase and new immigration flows

Source: Martel and Chagnon, Population Growth in Canada from 1851 to 2061, Statistics Canada

Given the importance of immigration from both population dynamics and ideological perspectives, regulations on admission of new residents are a strategic factor for the country. Hence, this policy includes specific features meant to sustain the steady immigration flows needed by Canada to help maintain relatively stable population growth and provide an influx of economically active people to maintain current productivity levels . . . [and who have] the qualities needed to adapt to the country’s society and effectively contribute to it.

Historically, Canada’s immigration policy has rested on three basic principles: selection of new immigrants, planning of immigration flows, and constant amending of the policy in response to specific needs of the job market and economy in a particular context.13

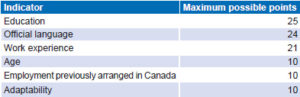

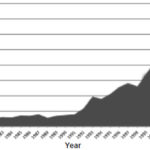

In the case of selection, the criterion for admission changed from being based on nation or region of origin to considering potential immigrants’ personal characteristics, such as age and educational level . . . This policy shift was determined by the restructuring of Canada’s economy after World War II, when industrial production replaced agricultural production as the most important economic driver. Currently, selection is based on a points system (Table 1), one of the main components of Canada’s immigrant policy. This instrument has enabled entry into Canada by a qualitatively consistent immigration flow with people high educational levels, competence in the official languages (for rapid insertion), relatively young average age, and prior work experience in specialized fields.

Although admission of new immigrants has been a constant in Canada’s immigration policy, the planning of immigration flows has also been a factor in the country’s approach. The planning process has gone through several phases . . . In the early 1900s, the number of immigrants accepted was based on “short-term absorption capacity.” This policy made the influx of new immigrants contingent on performance of the national economy and estimated short-term labor market needs. Since the mid 1980s, however, the focus has shifted to long-term planning.14 . . . The Canadian government began to be actively involved in immigration flow planning when CIC was instructed to submit an annual report on immigration to Parliament. Through these reports, Parliament is informed about the status of immigration flows, and admission plans for the following year are submitted and approved. The functioning of immigration regulations is also reviewed and any changes deemed necessary for the following years are proposed.

Table 1: Distribution of maximum points in Canada’s points system

Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2008

Provincial and regional governments also play an active role in immigration flow planning through regional programs that endorse admission of human resources to specific areas as needed, since these governments share jurisdiction on immigration issues with the federal government. In the case of the [relative rural] Province of Quebec, it asserts its prerogative to establish its own promotional programs and selection process, according to its specific needs.15 This type of strategy helps address the tendency toward high population density in urban areas reported in the last two census periods, peaking in the 2011 census (with over 69.1% of Canada’s population concentrated in urban areas).16

Periodic review of immigration regulations is another tenet of Canada’s immigration policy. In general, major changes in context (such as an economic crisis, for example) normally trigger changes in legislation on immigration, adjusting regulations to the country’s specific needs so that immigration flows do not become a deceleration factor damaging to Canadian society.

Application of a coherent immigration policy for almost 200 years (based on the previously described principles) and maintenance of stable and organized immigration rates have made Canada one of the world’s most important immigrant destinations. In demographic terms, the immigrant population accounted for 18% of the country’s population in the 2000 census, rising to 20.1% by 2006. In 2008, Canada had the highest permanent immigration rate in the world, approximately 0.8 [typographical error in Spanish: printed as 0.8%—Eds.] per 1000 inhabitants.17

13. Ivis Gutiérrez: Cubanos en Canadá: apuntes para una caracterización (1959-2011), p. 160.

14. Geneviève Bouchard: The Canadian Immigration System: An Overview; Peter Rekai: US and Canadian immigration policies. Marching together to different tunes.

15. Idem; y Nesta Scott: La política de inmigración en Canadá (Un triunfo de la inclusión sobre la exclusión).

16. Statcan: The Canadian Population in 2011: Population Counts and Growth.

17. Tina Chui and John Flanders: Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada, pp.11-12

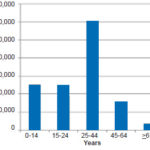

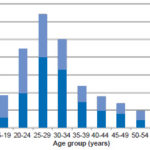

Canada’s immigration policy ensures that the population entering the country each year with permanent resident status tends to be very young, mostly of working age, and with high educational levels (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Educational level of permanent residents aged >15 years admitted to Canada in 2011

Source: Prepared by the author with data from Citizenship and Immigration Canada Facts and Figures, 2011

Figure 4: Immigrants by age group admitted to Canada in 2011

Source: Prepared by author with data from Citizenship and Immigration Canada Facts and Figures, 2011

Attracting new immigrants with ever-higher levels of professional skills is one of the aims of documents outlining the development strategies of important sectors such as science and technology, agriculture and defense. Canada’s science and technology strategy (Mobilizing Science and Technology to Canada’s Advantage) explicitly states that the country should be a magnet for talent, since population aging and the exodus of Canadians to work in other countries compels the country to create the conditions needed to “. . . attract, retain and develop the talent and ingenuity Canada needs.”18

18. Industry Canada: Mobilizing Science and Technology to Canada’s Advantage: Progress Report 2009, p. 18.

19. Department of Manpower and Immigration: Immigration Statistics (1967-1996).

20. Antonio Aja: Al cruzar la frontera.

21. Luin Goldring: Latinoamericanos en Canadá: Historia migratoria, el contexto de recepción y diversidad en las formas de transnacionalidad, pp. 17-18.

22. Malluli Díaz: Estudio del asentamiento de cubanos en Canadá. Yohanna de las M. Rodríguez: Los programas de promoción de inmigrantes implementados por Canadá y su influencia en los flujos migratorios cubanos.

CUBAN EMIGRATION TO CANADA: A CASE STUDY (1959–2012)

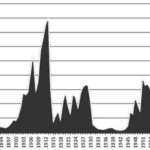

A case study on Cuba-to-Canada immigration shows how Canada’s immigration policy has succeeded in shaping immigration flows into the country. Immigration flows can be assessed not only from a population perspective but also from a human potential standpoint. In the case of Cubans residing in Canada, since the mid 1970s, CIC statistics have kept track of Cubans entering as permanent residents, and, while the numbers are low, the flow has been uninterrupted for the last 45 years (Figure 5).19

. . . Cuban immigration to Canada became increasingly more visible in the 1990s during the crisis known as the Special Period, which led to major changes in Cuba’s economic and social dynamics. Emigration became one of the strategies most used by individuals, not just looking for better opportunities but to help their families remaining at home . . . Concomitantly, a destination “diversification” process of Cuban emigration took place, leading to ever-larger numbers of Cubans becoming permanent residents in nontraditional destinations such as Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom and Canada, among other countries.20

Canada is currently the fifth most popular destination for Cuban emigrants, after the United States, Spain, Mexico and Italy. Cuban immigration to Canada has unique features compared with other destinations since it occurs in the context of the immigration policy described above. However, other factors are also at play, such as well-established family, professional and social networks resulting from the history of exchanges between the two countries, and Canada’s long tradition of admitting refugees.

. . . Cubans residing in Canada do not constitute a sizable immigrant group, not even within the collective immigration flows from Latin America and the Caribbean (including immigrants from Mexico, Chile and Jamaica, which have a stronger history and tradition of immigration to Canada).21 However, from Cuba’s perspective, it is an interesting case study because of the volume of immigrants involved in the flow, the absence of policies of exception in admission and insertion of Cuban immigrants, and the cordial political relations maintained between the two countries.

The main reasons given by Cubans in Canada for their choice of destination include the possibilities for legal immigration and regularization offered by Canada; job opportunities; Canada’s political and economic stability and high standard of living; government programs for adaptation and insertion; and stable political and diplomatic relations between the two countries. Another factor influencing their decision is Canada’s comprehensive social benefits program, especially free health care. On the other hand, factors viewed as obstacles for insertion in Canada include the language barrier, the climate, and difficulties in finding work commensurate with qualifications obtained in Cuba.22

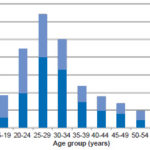

. . . This group’s average age is relatively young: a significant percentage aged 20–39 years. Statistics show the sexes are evenly distributed and educational levels are high, with many university graduates. The Cuban population in Canada is not very different from other immigrant groups [by age] (Figure 6) . . . An age-structure analysis (data from 1973 to 1996) shows that the most active subjects were in the group aged 20–34 years, in particular the cohort aged 25–29 years.

Figure 5: Annual admission to Canada of new permanent residents born in Cuba

Source: Prepared by author with data from Citizenship and Immigration Statistics (1966–1996) and Citizenship and Immigration Canada Facts and Figures (2002, 2003, 2008, 2010 and 2011)

Figure 6: Distribution by age group and sex of Cuban immigrants admitted to Canada, 1973–1996

Source: Prepared by author with data from Citizenship and Immigration Statistics (1966–1996)

As for gender distribution, from 1973 to 1996 significantly more men (actually twice the number of Cuban women) immigrated to Canada (Figure 6). This trend was common among immigration flows around the world during this period and, given the male-oriented division of labor, Cuban women did not have much opportunity to go to Canada except as partners or relatives in the family reunification process. By the late 1990s, however, immigration flows of women around the globe rose significantly, with the distinctive feature that women were undertaking the immigration process independently and traveling alone to the destination country . . .

In the late 1990s, the age distribution of Cubans residing in Canada was similar to the figures mentioned above (70% of Cubans immigrating to Canada by 2008 were in the group aged 20–50 years).23 The number of women immigrants, however, was rising: women accounted for 62.5% of the total Cuban population permanently residing in Canada from 2000 to 2011.24 Other factors that played a role in the growing number of women include the fact that a great many more were being trained as a result of equal access to higher education and the incidence of marriage between Cuban and Canadian nationals;25 at the time of study these data were not available.

Concerning racial composition, Canada’s Cuban-born immigrant community is similar to Cuban emigration in general: predominantly white (as self-defined by 49.2% of the total population, according to Canada’s 2011 population census).26 Almost half (49.5%) are married. This figure includes a large number of individuals married to nationals . . . However, it must also be kept in mind that Canada’s legal immigration programs not only provide for the right of families to be reunited once they are settled in the host country but also promote admission of entire families to establish themselves as new residents, since having the whole family there promotes their adaptation to Canadian society.27 . . .

Another interesting feature is the skills levels of those granted permanent residency. Earlier studies of Cuban residents in Canada show many immigrants with high educational levels. In 2008, 54% of the group studied had at least a bachelor’s degree and 22% reported some type of university-level education. The largest concentration of university graduates was found in the group aged 30–40 years, with women accounting for 52%. In the group aged 40–50 years, 34% of the total population had attended institutions of higher education, 40% of them women. The group aged 20–30 years had the fewest university graduates, but the highest proportion of women among them: 59% of the total with university degrees.28 This pattern suggests that the younger Cuban women are, the more educated they are compared to their male counterparts. The potential contribution of these women to the country’s birth rate should also be taken into account since they are in the age group with the highest fertility rates.

With respect to the participation of Cuban residents in Canada’s workforce, the most common professions are in technical fields followed by social sciences and humanities. Although this pattern has been part of the dynamic of Cuba-to-Canada immigration since the late 1960s, it has become more pronounced with the increasing number of Cubans settling in Canada since the 1990s.29 Recent studies show that this trend has continued and is constant, with engineering and computer sciences predominating.30 . . . According to Malluli Díaz,31 the percentage of Cuban professionals residing in Canada is substantial, but the number of those finding employment commensurate with their professional skills is not.

23. Malluli Díaz: Estudio del asentamiento de cubanos en Canadá.

24. Yohanna de las M. Rodríguez: Los programas de promoción de inmigrantes implementados por Canadá y su influencia en los flujos migratorios cubanos.

25. Idem.

26. Idem.

27. Citizenship and Immigration: Canada Facts and Figures. Immigration overview. Permanent and temporary residents.

28. Malluli Díaz: Estudio del asentamiento de cubanos en Canadá.

29. Department of Manpower and Immigration: Immigration Statistics (1967-1996).

Cuban immigration to Canada includes a large component of skilled workers as a result of the impact of migration policy in the country of origin, which plays an important role in shaping features of migration flows. The effects of the 1990s economic crisis, however, should not be discounted: it led many people to leave Cuba in search of “new lands where they could solve the problems of daily life and continue seeking new directions and perspectives for the future.”32

It is important to examine the effects that this migration flow can cause in the country of origin. For example, preferential recruitment of young people could exacerbate the problem of Cuba’s aging population, particularly since the group aged 20–30 years is among the most economically active in the migration flows33 and is also in full reproductive age. Departure of skilled workers is a challenge for Cuba’s development at a time in the country’s history when it must rely on human potential to modernize the economy.

CONCLUSIONS

As was observed in the first section of this study, immigration plays a fundamental role in Canada’s population and its growth dynamics. The numbers reveal how Canada has increasingly depended on new immigration flows to maintain stable population growth rates as well as productivity and development. This indicates that the country is and will continue to be reliant on new immigration flows . . .

Immigration is essential for Canada, but not all applicants are accepted. According to the government, admission to the country is a privilege, not a right, and Canada will continue to be selective about who may enter and, equally important, who may not.34 The country’s immigration admission policy for new permanent residents becomes strategic, and selectivity and immigration planning become fundamental tools to help ensure that people entering Canada can effectively make contributions in different economic sectors.

The case study of Cuban immigrants in Canada shows how immigration policies can influence the configuration of the flow of immigrants with similar qualifications: relatively young people with high educational levels and specialization in branches of knowledge in demand by the economy of the host country and who have knowledge of the official languages to ensure rapid insertion in the destination society. Such policies, however, benefit destination countries but not countries of origin, such as Cuba, which is left with significant challenges: preserving the human potential of economically active age groups and facing the loss of reproductive-age population. These impacts are even greater in the context of Cuba’s current transition to having one of the oldest populations in the hemisphere and for modernizing its political economy, for which human potential is critically important in the country’s development plans.

Bibliography available online at Gutierrez_bibliography.pdf

THE AUTHOR

Ivis Gutiérrez Guerra (igg@rect.uh.cu), sociologist with master’s degree in social development and doctorate in economics, Center for International Migration Studies, University of Havana, Cuba.

30. Yohanna de las M. Rodríguez: Los programas de promoción de inmigrantes implementados por Canadá y su influencia en los flujos migratorios cubanos.

31. Malluli Díaz: Estudio del asentamiento de cubanos en Canadá.

32. Antonio Aja: Tendencias y retos de Cuba ante el tema de la emigración, p. 13.

33. ONE: Proyecciones de la población cubana 2010–2013.

34. Canadian Government, Multiculturalism in Canada, p. 10.

THE AUTHOR

Luisa Iñiguez Rojas, Center for the Study of Human Health and Wellbeing, University of Havana, Cuba.