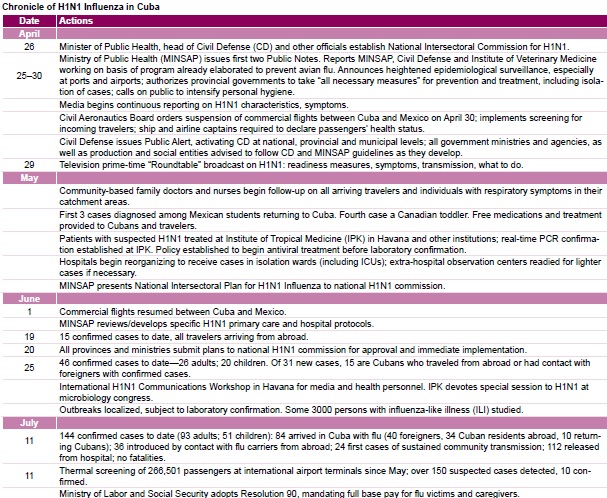

Last April, the same week that the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency due to influenza A(H1N1), Cuban government and public health authorities met to chart a course for prevention and management of the flu that by year’s end had become pandemic, spreading to some 200 countries.

Like disaster response, epidemic-containment strategies depend largely on the situation before catastrophe: the resources and infrastructure at hand, readiness planning already in place, general population health, and social determinants like education and culture. Epidemic response must also take into account the unpredictability of the disease’s biological agent—in this case, a novel virus whose lethality and mutation probability were unknown.

Squaring off against H1N1, Cuba’s 11.2 million people had several things working for them and quite a few against. On the negative side, the global recession was hitting hard, making 2009 the most economically dim year for Cuba since the 1990s and prompting a complete overhaul of land use to urgently increase food production. Fresh resources were exceptionally scarce. What’s more, they depended in large part on continued promotion of international tourism, Cuba’s second highest earner of hard currency.

Second, while the general health picture was positive, some factors present were later associated with high risk for H1N1: several thousand more pregnancies in 2009 compared to the year before;[1] relatively high asthma prevalence (about 13%, according to the most recent national survey);[2] and an epidemiological profile that leaned strongly towards other non-communicable chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and heart disease. In addition, influenza and pneumonia were already the fourth cause of death on the island, the 2008 adjusted rate (28.9 per 100,000 population) slightly up from 2007 (25.4 per 100,000 population).[3] Cuban health authorities could predict an exacerbation of asthma attacks, as well as seasonal flu, colds and all acute respiratory infections come November, as the country’s fickle climate would bring warm, sunny days turning to chilly, humid nights.

During 2009, the health system itself was still in the throes of reorganization at the primary care level in some provinces, and many secondary and tertiary institutions were in the midst of refurbishing. Going into the fall, Havana City was also handling simultaneous, localized outbreaks of viral conjunctivitis and dengue.

Finally, there were the cultural factors: “Cubans don’t go to the doctor for a cold,” says Dr Manuel Villar, Deputy Director for Urgent Care at the Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital in Havana, indicating that risk perception would be a persistent challenge. But perhaps more worrisome was what Dr Luis Estruch, Vice Minister of Public Health, calls Cuba’s “kissing culture”. “Mere acquaintances in Cuba greet each other with bear hugs, women are kissed on the cheek…anything less is just impolite.”

On the positive side for Cuba were several key social determinants, most importantly high levels of education, especially among women (99.8% literacy and constituting 62% of the professional and technical workforce),[4] and access to water (76.7% of population with connection to safe drinking water at home; nearly 100% with public or easy access).[5] Other important resources to confront the epidemic were the single, universal public health system offering free health services; primary care coverage in all 169 municipalities; a proven early-warning system for epidemiological surveillance; formidable health indicators (4.8 per 1,000 live births infant mortality in 2009 and 99.4% child survival at 5 years in 2008);[1,5] and a history of public involvement in containing earlier epidemics,[6] vaccination drives, vector control, and disaster preparedness and recovery. In the latter, coordinated by Civil Defense, the public health sector has played a central role.[7] Taken together, these factors have produced public engagement and palpable confidence in health and disaster mitigation programs.[8]

Evolution of Cuba’s H1N1 Strategies

Cuba’s H1N1 approaches evolved over time, the main guidelines adapted from contingency plans already in place against a possible outbreak of avian flu (H5N1) and designed at the outset for a “worst-case scenario”. The following report on development, implementation and initial results of the national effort was written from several in-depth interviews with Dr Estruch, staff at Havana’s Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital, other health professionals, and patients. In addition, the epidemic’s “public record” was consulted through review of government alerts, ministerial resolutions, media coverage and educational materials on H1N1 prevention.

The strategy for confronting influenza A(H1N1) in Cuba can be divided into 7 areas:

- Intersectoral leadership, centralized coordination

- Epidemiological surveillance and control

- Public information and engagement

- Active screening of risk groups

- Clinical protocols and research

- Adaptation of hospitals and other health facilities

- International cooperation

Intersectoral leadership, centralized coordination In late April, coordination of the effort was entrusted to a national commission headed by Civil Defense, with the Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP) providing strategic direction for epidemiological surveillance, prevention measures and clinical management. The commission included delegates from 15 ministries, plus provincial government representatives; this intersectoral composition was replicated at the provincial level. It is worth noting that in Cuba, only Civil Defense national headquarters is a permanent body; all other levels are civilians mobilized for national emergencies, disasters or epidemics, with provincial government heads automatically assuming the role of civil defense chiefs in their territories.

While the National Intersectoral Plan for Influenza A(H1N1) was not officially approved until late May, the commission had already begun adopting measures as early as April 28. Commission meetings—often daily from then on—served to update international information, review Cuba’s situation nationally as well as in each sector and province, and refine tactics at different stages of the epidemic and within different population groups.

Under this H1N1 Plan, each ministry and province was given responsibility for actions in its own domains in what amounts to the broadest intersectoral campaign launched in Cuba outside of hurricane season.

In July, the commission called on the Labor and Social Security Ministry to issue a special resolution mandating full base pay for employees with H1N1, for those whose workplaces shut down due to the epidemic, and for mothers caring for sick children or children whose school or classroom were closed.[9] Through the end of 2009, no schools were shut, although a number of classrooms were sent home and dormitory sections isolated for 7 to 10 days.

The Tourism Ministry began alerting hotel and restaurant chains, tourist agencies, and the travel industry in general, providing H1N1 prevention information for employees and patrons. The Transportation Ministry posted stickers in interprovincial buses and local public transportation, including taxi fleets. Public service announcements were distributed to bus stations. Cleaning crews were provided with disinfectants to scrub down bus doors, railings and seats.

Production sectors were also assigned roles: essential stocks of oseltamivir (generic Tamiflu®) were guaranteed by the pharmaceutical industry, and several textile plants around the country began round-the-clock shifts to produce several hundred thousand face masks for health workers, customs and immigration personnel, among others.

Before the Culture Ministry loomed a series of large events going into the epidemic’s predictable peak period: the London Royal Ballet’s performances in September (5 ballerinas were diagnosed with H1N1 in Havana); the September 20th “Peace without Borders Concert” in Havana’s Revolution Square (attended by over one million people); and the early December New Latin American Film Festival, traditionally a draw for thousands. But events were not cancelled. Instead, says Dr Estruch, prevention relied on airport epidemiological surveillance and on the public information campaign.

An H1N1 advisory circulates on the dashboard of a Havana taxicab. Photo credit: E Añé

The Ministries of Education and Higher Education were charged with the especially difficult task of mounting preventive efforts in the country’s 12,000 schools where over 2 million students were enrolled. According to Idelsis Brito, a fourth-grade teacher hospitalized with H1N1 this January, such measures in her Havana school included suspension of the morning assembly, which normally begins the school day all over Cuba. “Canceling the assemblies was a general orientation to avoid unnecessary conglomeration of students,” she told me. As a result of the guidelines, she said, “We also took more care to make sure children washed their hands before snacks and lunch, and reinforced messages about hygiene and flu-like symptoms.” School administrators were advised to report respiratory cases to their local community polyclinic for follow-up. Schools told parents to keep symptomatic children at home and see a doctor at once.

University and high school boarding students would prove more difficult and require special attention, since generally low risk perception in this age group would conspire with dormitory living—just when emerging international evidence was flagging young adults among the groups accounting for the majority of cases in some countries.[10]

Epidemiological surveillance and control It was, in fact, among university students that the first H1N1 cases were detected in early May: 3 Mexican medical students returning to a Matanzas Province campus, whose cases were confirmed by real-time PCR at Havana’s Pedro Kourí Institute of Tropical Medicine (IPK, its Spanish acronym). The entire group of 150 traveling from Mexico was isolated at the school for 15 days and treated preventively with oseltamivir, as were university faculty and workers in contact with them—485 persons in all—in order to contain the chain of transmission.

These first cases also illustrate the particular complications Cuba faced with travel to and from the island: in addition to over 2 million tourists annually, regular passengers at the country’s airports include over 70,000 Cubans serving abroad—most of them health professionals—and another 30,000 foreign students studying in Cuban universities.

Early measures were instituted at international ports and airports: captain’s declaration of passenger health status, plus active passenger screening by public health nurses and doctors. From May forward, all incoming passengers—Cubans and foreigners alike—were required to complete a health questionnaire. Eventually, these were supplemented with thermal sensors at airport terminals to detect body temperatures over 37.5°C. Healthy travelers were given a card advising them of H1N1 symptoms and urging them to see their family doctor or visit hotel medical posts if they felt ill. Cubans received follow-up visits by family nurses or doctors within 72 hours after returning home, and all travelers were subject to follow-up for as long as 10 days.

Passengers with fever and respiratory symptoms were evaluated at airport isolation units, and, if necessary, hospitalized or treated at their hotels. Despite the fact that all treatment was provided free of charge, this measure ruffled some tourists early on, a few of whom complained that they ended up spending their vacation in an isolation ward.

The other early measure that caused some international displeasure was Cuba’s decision—along with Argentina, Ecuador and Peru—to temporarily suspend commercial flights to and from Mexico.[11] However, Dr Estruch defends the move: “At that time, no one knew how aggressive the virus would be, how contagious; Mexican authorities were themselves cancelling classes, soccer matches and other events; and people were dying. We had the option of canceling flights for a period, while countries like the United States, with a land border and so many travelers, really didn’t have that option. US authorities recommended travelers postpone plans to visit Mexico.”

Domestically, MINSAP’s provincial and municipal hygiene and epidemiology centers collected data on local cases, suspected cases, deaths and their demographics from family doctors, community-based polyclinic epidemiological centers, and hospitalization records, which were then fed into a national data base at MINSAP. Alerts of possible localized outbreaks of influenza-like illness (ILI) in schools, university dormitories, workplaces, prisons and other population centers were also reported, and these were handled by treating patient groups (including laboratory confirmation) and isolating when feasible. Of nearly 800 ILI outbreaks recorded through the end of 2009, 185 were confirmed as H1N1.

From April through December, H1N1 proceeded through various transmission routes: no transmission (no local transmission; imported cases only); limited local transmission (local circulation limited to imported cases and their local contacts); and sustained community transmission (virus circulating among local residents with no established link to imported cases or their contacts). The epidemic phase of the influenza began in September, with the virus widely circulating in all provinces.

Until late June, transmission was limited to imported cases (15 confirmed cases, all among travelers from abroad). On June 25, health authorities announced the first cases among Cubans in contact with travelers (“introduced cases”), with total confirmed cases at 46. On July 11, they reported the first 24 cases due to sustained community transmission among a total of 144. Another 84 of these cases were imported; 36 introduced. The proportion of sustained community transmission rose from August through November, during the epidemic phase.

By late August, children and young adults with underlying chronic conditions, plus women who were either pregnant or had just given birth, were beginning to emerge as the most vulnerable groups—consistent with the global behavior of the pandemic. The first H1N1 deaths were reported in early October: 3 pregnant women. Through December, of 973 confirmed cases and 41 total fatalities, 9 deaths were reported among pregnant and postpartum women, and 5 among children. All the children suffered from conditions already compromising their health: 3 had cerebral paralysis, and 2 had leukemia.

Public information and engagement Dr Estruch notes that elevating risk perception has been one of the main challenges to achieving behavioral changes that help prevent viral transmission. His team set up weekly meetings with Cuban reporters, creators of public service announcements (PSAs) and National Health Promotion Center staff. As a result, the epidemic was consistently covered in the Cuban press, and the media ran a total of 24 PSAs during 2009. The youth paper, Juventud Rebelde, also published and distributed a series of supplements on H1N1 prevention. In addition, the national health system’s web portal, INFOMED, generated a special site for health professionals with information updated daily from global and national sources (http://ah1n1.sld.cu).

A jolt to public awareness came with the announcement of the first fatalities, all pregnant women, in October. From then on, many of the hospitalized patients filmed and interviewed for nightly news came from this high-risk group. “These women’s stories emphasized the real threat the virus presented,” comments Dr Estruch.

Labor unions, churches, block organizations and the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC, its Spanish acronym) became engaged at the local level—the goal being to achieve the active partnership needed for effective prevention, between public health authorities, communities and members of vulnerable populations.[12]

Active screening of risk groups The FMC was involved in a particularly innovative strategy that took advantage of Cuba’s universal primary care network. FMC health promoters joined family doctors and nurses, plus medical and nursing students, to go door-to-door to seek out residents most at risk. Advised to make daily home visits, they reminded these people to see their doctor upon appearance of respiratory symptoms or fever, and also found people who were already symptomatic. From September through December, repeated house calls were thus made to over 80,000 of the country’s pregnant and postpartum women (over 90% of total), as well as to nearly 75,000 children under one year. [1,13] Similar efforts were pursued among the country’s 40,000 children with disabilities at home and in child care centers and schools; other children with specific underlying conditions; as well as adult asthmatics and those with chronic respiratory conditions.

Active screening provided a layer of “community triage” in which cases identified were either treated locally by family and polyclinic physicians or referred by them to specific hospitals, depending on risk group and severity of symptoms. For example, guidelines indicated admission for all symptomatic pregnant and postpartum women, as well as for infants, asthmatics and children with underlying conditions such as diabetes, or neurological or motor disorders. They were admitted either to hospitals or to observation and treatment centers established for cases of mild ILI.

Home stay under a family doctor’s care was indicated for children without associated risk factors, and for adults with milder symptoms. From September through December, some 57,000 ILI cases, including 15,999 pregnant women and 1154 postpartum women, were admitted to hospitals or observation and treatment centers. Of the pregnant and postpartum women, 419 required ICU hospitalization. Another 128,504 people were hospitalized at home for a required week.[1]

Early identification of cases also facilitated earlier treatment, an important factor since the global experience was showing that antivirals were most effective when given within the first 48 hours after onset of symptoms.

Clinical and laboratory protocols Earlier epidemic-specific guidelines on aspects such as patient flow, isolation, case management, and health-worker protection, as well as l aboratory analysis, were adapted for the H1N1 influenza.

Throughout 2009, the Pedro Kouri Institute of Tropical Medicine, a WHO/PAHO Collaborating Center for the Study of Viral Diseases, was established as the national reference laboratory for confirming H1N1 cases. The IPK is also expected to lead continuing research on H1N1 and its behavior in Cuba over time.

In the early months, laboratory confirmation was applied to all suspected cases, but later, the lab used real-time PCR only for establishing extent of H1N1 circulation in the country (through sentinel sites), identifying viruses responsible for specific outbreaks in population clusters, and for studying serious cases. Thus, the “treat-before-confirmation” national policy became “treat- without-confirmation”.

Clinical management of suspected H1N1 was reviewed by expert panels, which issued new guidelines for certain population groups, such as pregnant and postpartum women. For example, in June, a panel at Havana’s Enrique Cabrera General Teaching Hospital led by Dr Albadio Pérez, head of the national critical care expert group, was charged with developing guidelines for management of obstetric patients with suspected H1N1. Relying on their own protocols and experience, as well as other international expert opinion and WHO/PAHO guides for managing H1N1, the resulting norms were later adopted and published for national use.[14] Among other aspects, the document covers clinical diagnostic criteria; primary antiviral treatment regimen (two 75 mg doses of oseltamivir daily); hospitalization criteria; intensive care (ICU) admission criteria; main complications and their treatment protocols; and step-by-step management from initial reception and triage through all stages of illness, hospital care and follow-up.

The Enrique Cabrera hospital, reference center for complex obstetric cases from 2 provinces (including Havana City), and now the institution designated to receive all pregnant and postpartum women with ILI in those provinces, also became the pilot institution for testing the new guidelines. By year’s end, the staff had achieved commendable results: of the 2300 pregnant and postpartum women admitted with ILI between June 2009 and January 15, 2010 (135 into a special ICU), only one fatality was registered.

Adaptation of hospitals and other health facilities Health care facilities, from primary to tertiary care, began preparing to receive patients in May. Isolation wards were set up at hospitals in all provinces, and other health facilities were converted into observation and treatment centers to accommodate milder cases. By the time the epidemic phase set in, provinces were concentrating serious ILI cases in designated hospitals’ ICUs. But all of Cuba’s over 120 hospital ICUs and some 100 municipal (mainly polyclinic) ICUs were readied for H1N1 patients if needed, their total capacity expanded to over 2000 beds.

The Enrique Cabrera hospital also offers a good example of Cuban hospitals’ transformation in the face of H1N1. The 477-bed institution reorganized patient flow, employee shifts and physical spaces to handle the influx of cases. The key, says its director, Dr Armando Garrido, was reorganization and staff commitment to the discipline imposed by the dangers of viral transmission. “We received some extra resources, but these were not the most important thing,” he noted. The hospital set up special triage areas for receiving suspected H1N1 patients, five 20-bed isolation wards for admission, and an acute respiratory ICU with 20 beds (separate from their 60-bed ICU) exclusively for pregnant and postpartum women. The latter was particularly important since WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) was warning that pregnant women with H1N1 were ten times more likely to need ICU hospitalization than other flu patients.[10]

Swift application of antivirals at the Havana hospital was confirmed to me by Idelsis Brito, the teacher. She was 7 months pregnant when referred by her family doctor for shortness of breath, cough and fever. “I received the first pill when I was still being processed for admission,” she said. After 3 days in the ICU, her symptoms relieved, she was about to be released into the isolation ward. Domestically-produced generic antivirals are in sufficient supply, according to health officials, but restricted to medical prescription and available free-of-charge only through physicians or hospital pharmacies to avoid indiscriminate use.

The biggest challenge for the hospital, says Dr Garrido—a veteran of Cuban disaster relief in Pakistan and Bolivia—has been maintaining the quality of other hospital services during the epidemic. While evaluation is still underway, at least one of the institution’s indicators is noteworthy: of 4330 births in 2009—including a share of complex cases—the hospital registered 1.58 per 1000 live births infant mortality.

International Cooperation Cuban health authorities collaborated with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and WHO over the course of the epidemic, generating reports required by International Health Regulations (2005) and participating in PAHO Executive sessions on H1N1. “Cuba is prepared (for H1N1),” said Dr Lea Guido, PAHO/WHO resident representative in Havana last April, noting the agency had stepped up its communication and cooperation with local health authorities.[15] In October, WHO Director Dr Margaret Chan visited Havana, where she praised the “good work” against H1N1 and announced Cuba was among the 95 low- and middle-income countries on the list to receive WHO-donated vaccines once manufacturers released enough doses.[16,17]

Current Situation and Lessons

The 2009 pandemic’s second wave is waning in the northern hemisphere, Cuba included. By January 2010, at least 14,000 deaths were reported worldwide from laboratory-confirmed cases, half of these in the Americas and 53 in Cuba.[18,19] At the height of the epidemic, Cuban health facilities reported 150,000 cases of acute respiratory infections weekly, including all types of influenza, colds, and a minority of confirmed H1N1 cases.

What is to be learned from the Cuban experience to date? Health authorities are the first to admit they don’t have all the answers, and, in fact, need to work toward generating earlier risk perception, greater consistency in implementing prevention measures, and long-term change in individual habits to ensure better hygiene. Nevertheless, the overall positive results of their battle with H1N1 may offer some useful lessons:

Importance of coordinated, intersectoral strategies for effective planning, prevention and management. Cuba’s response was aided by the fact that a plan for avian flu was already in place.

Consistent access to reliable epidemiological information nationally and internationally: an “early warning system” already in place (a lesson learned by Cuba in the 1992–93 neuropathy epidemic).

Fast action from the start to break chains of transmission wherever possible.

A strong public health system with accessible primary care as a frontline defense in public health emergencies. The family doctors and nurses, and community-based polyclinics played a central role in early detection, home hospitalization and follow-up.

Active screening of at-risk populations, involving community health promoters as well as medical personnel, cut precious time between onset of symptoms and treatment, saving lives and also limiting the burden on ICU facilities.

Early and persistent public education to increase risk perception, especially in most vulnerable groups. Health educators are now studying ways to better target messages, especially for young adults.

Monitoring, to ensure more consistent application of measures in all ministries and provinces. This is one of the most difficult things to achieve, given the massive involvement of people in all sectors and the general public as well.

Importance of increasing global health cooperation.

The virus behaved in Cuba much like it did in other countries: H1N1 was especially hard on pregnant and postpartum women and small children, and tended to attack young adults more than seniors. Individuals with comorbidities were especially at risk: a January 2010 PAHO report establishes that 60–77% of deaths in 8 countries of the Americas were among such patients. The same report indicates that asthma constituted the most frequent comorbidity among hospitalized patients in Chile (17%),[18] coinciding with empirical evidence from Cuba that this may be the single most dangerous underlying condition.

Clinically, as in other countries, pregnant and postpartum women, as well as immunosuppressed patients generally, tended to develop bacterial infection on top of the influenza, rapidly complicating their condition and proceeding quickly to pneumonia.

The IPK, National Genetics Center, and other research institutions have worked with hospital specialists to begin long-term study of the virus and its impact on specific population groups.

Ongoing research is being carried out based on fluid aspiration from the lungs of deceased patients. Another important area for study is whether the 895,573 Cubans vaccinated against seasonal flu will show any increased immunity against H1N1 as some literature is beginning to suggest. The risk groups vaccinated included persons over 75 years old, young adults with severe asthma, diabetics, and persons on dialysis, plus certain categories of workers.[20]

The most sobering lesson of the 2009 pandemic for Cuba and other developing countries, however, does not depend on the quality and efficiency of their health care systems. Despite what Dr Estruch calls the “highly ethical and humanitarian posture” of WHO itself, both the international agency and national governments and their health authorities are dependent on the generosity of richer nations and pharmaceutical companies for access to potentially life-saving vaccines.

In the current pandemic, WHO is attempting to muster enough vaccines to cover 10% of the population in 95 countries, 35 of them prioritized—including Cuba. Yet, at this writing, vaccine lots are being shipped to only 3 countries, while, in contrast, current supplies are enough for 35% of residents in places like the United States.[21,22] In a recent essay, Laurie Garrett and Dana March put it more bluntly: “The rich countries demand that the planet’s poor make sacrifices to slow down epidemics…but offer little in return, including access to precious vaccines.”[23]

But as luck would have it, H1N1 has been mild thus far. Just a rehearsal.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Laurie Garrett of the Council on Foreign Relations, USA, for her insights into the H1N1 pandemic, and for graciously sharing resources and interview time.

- De la Osa JA. ¡¡4,8!! Granma. 2010 Jan 4.

- Venero S, González F, Suárez R, Fabré D, Fernández H. Epidemiology of Asthma Mortality in Cuba and its Relation to Climate, 1989 to 2003. MEDICC Review. 2008 Summer;10(3):24–8.

- Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2008. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU), National Medical Records and Health Statistics Bureau; 2009. p 43.

- Informe sobre desarrollo humano 2007–2008. New York: United Nations Development Program; 2007. pp 271 and 332.

- Situación de salud en Cuba. Indicadores básicos 2008. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU), National Medical Records and Health Statistics Bureau; 2009.

- Rojas Ochoa F. Cuba’s Epidemic-Fighting Model. MEDICC Review [serial on the Internet]. 2005 Jul [cited 2009 Dec 30];7(7):2–5. Available from: http://www.medicc.org/publications/medicc_review/0705/spotlight.html

- Mesa G. The Cuban Health Sector and Disaster Mitigation. MEDICC Review. 2008 Summer;10(3):5–8.

- Thompson M. Weathering the Storm: Lessons in Risk Reduction from Cuba. Boston: OXFAM America; 2004.

- Pérez L. Tratamiento laboral y salarial ante la influenza A H1N1. Granma. 2009 Nov 11.

- WHO: Global Alert and Response (GAR) [homepage on the Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 briefing note 14: Experts advise WHO on pandemic vaccine policies and strategies; 2009 Oct 30 [cited 2009 Nov 2]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/briefing_20091030/en/

- Thomas. ALTA felicita a Ecuador por levantar las restricciones de viajes. Revista Aerea [serial on the Internet]. 2009 May 9 [cited 2009 Nov 2]. Available from: http://www.revistaaerea.com/2009/05/09/alta-felicita-a-ecuador-por-levantar-las-restricciones-a-los-viajes/

- Hutchins S, Truman B, Merlin T, Redd S. Protecting Vulnerable Populations from Pandemic Influenza in the United States: A Strategic Imperative. Am J Public Health. 2009 Sep 2;99(S2):S243–S248.

- De la Osa JA. Acerca del A H1N1. Realiza Cuba acción de salud sin precedentes con las embarazadas. Granma. 2009 Dec 16.

- For full guidelines, see Guía de diagnóstico y tratamiento en cuidados intensivos de pacientes obstétricas con influenza A(H1N1). Available from: http://www.sld.cu/galerias/pdf/sitios/urgencia/guia_de_diagnostico_y_tratamiento_en_uci_de_la_paciente_obstetrica_con_influenza_h1n1_grave..pdf

- De la Osa JA. Cuba está preparada ante la epidemia del virus A H1N1. Granma. 2009 Apr 6.

- De la Osa JA. Ustedes han hecho un buen trabajo en salud. Granma [serial on the Internet]. 2009 Oct 26 [cited 30 Dec 2009]. Available from: http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/2009/10/26/nacional/artic03.html

- Pérez D. Capacidad global de vacunas contra la Influenza A (H1N1) es limitada e inadecuada. Juventud Rebelde [serial on the Internet]. 2009 Oct 27 [cited 30 Dec 2009]. Available from: http://www.juventudrebelde.cu/cuba/2009-10-27/capacidad-global-de-vacunas-contra-la-influenza-a-h1n1-es-limitada-e-inadecuada/

- PAHO: Epidemiological Alerts [homepage on the Internet]. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; c2007–2010. Regional Update, Pandemic (H1N1) 2009; 2010 Jan 11 [cited 2010 Jan 20]. Available from: http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2192&Itemid=1167&lang=en

- WHO: Global Alert and Response (GAR) [homepage on the Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Disease Outbreak and News. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 – Update 84; 2010 Jan 22 [cited 2010 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2010_01_22/en/index.html

- De la Osa JA. Cerró con éxito vacunación contra virus estacional de la gripe. Granma. 2009 Dec 2.

- Bartlett JG. 2009-2010 H1N1: What’s New This Week – January 4, 2010. Medscape Today [serial on the Internet]. 2010 Jan 5 [cited 2010 Jan 22]. Available from: http://medscape.com/viewarticle/714506.

- Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccine deployment update – 23 December, 2009 [monograph on the Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 Dec 23 [cited 2010 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/vaccines/h1n1_vaccination_deployment_update_20091223.pdf

- Garrett L, March D. The long-term evidence for vaccines. Newsweek [serial on the Internet]. 2009 Dec 7 [cited 2010 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.newsweek.com/id/226097

“Life is in your hands”, one of 3 newspaper supplements published on H1N1. Photo credit: E Añé

“Life is in your hands”, one of 3 newspaper supplements published on H1N1. Photo credit: E Añé

Expectant mother Idelsis Brito: early treatment key to recovery. Photo credit: G Reed

Expectant mother Idelsis Brito: early treatment key to recovery. Photo credit: G Reed