ABSTRACT

Cuba’s maternity homes were founded in 1962 as part of the general movement to extend health services to the whole population in the context of the post-1959 social transformations. The overarching goal of the homes was to improve the health of pregnant women, mothers and newborns. Hence, in the beginning when there were few hospitals in Cuba’s rural areas, their initial purpose was to increase institutional births by providing pregnant women a homelike environment closer to hospitals. There, they lived during the final weeks before delivery, where they received medical care, room and board free of charge. Over time, and with expanded access to community and hospital health facilities across Cuba, the numbers, activities, modalities and criteria for admission also changed. In particular, in addition to geographical considerations, expectant mothers with defined risk factors were prioritized. For example, during the 1990s economic crisis, the maternity homes’ role in healthy nutrition became paramount. The purpose of this essay is to provide a historical perspective of this process, describe the changes and results during the 55 years examined, and take a critical look at the challenges to successful implementation of this model, a mainstay at the primary healthcare level of the public health system’s Maternal–Child Health Program.

KEYWORDS Maternal health, maternal–child health, obstetrics, pregnancy, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

Throughout history and in different parts of the world, the term “maternity home” conjures up a variety of notions and descriptions. These institutions, which nearly always refer to facilities where women live and receive medical attention during some period of their pregnancy, have also been known as “maternal homes,” “maternal waiting homes,” and “centers for protection of rural women.”[1,2] In 1891, the prominent obstetrician Adolphe Pinard founded a shelter for poor Parisian women who were pregnant, and whose delivery and medical services were provided free of charge by Pinard and his colleagues. Similar institutions later sprang up in Sweden, the USA and Latin America, but without notable expansion into the 20th century. It wasn’t until the 1950s, faced with alarming maternal mortality, that similar homes appeared near hospitals for women in rural areas of poorer countries.[3,4]

IMPORTANCE This paper describes and analyzes Cuba’s 55-year experience with maternity homes for vulnerable and at-risk pregnant women, admitted or day boarders in the weeks and months before giving birth. The institution was founded at the primary care level as part of the nation’s implementation of the right to health in the context of limited resources.

In Cuba, as elsewhere, early versions of maternity homes were destined for poor women, and in the 18th century particularly for “disgraced” single women, to hide their shame from society during the last months of pregnancy. Pinard’s influence later found disciples on the island, in particular with Dr Eusebio Hernández Pérez, who took the maternity home idea to heart. And while no homes as such were created, a four-bed ward was set aside in Havana’s América Arias Maternity Hospital, known as the “maternity home.” The ward was intended for single women who had nowhere to live before or after delivery, since most were domestic workers whose employers fired them prior to giving birth. Supported by charitable donations, such initiative disappeared in the 1920s.[5]

A NEW HOME IN A NEW SOCIETY

The creation of the first maternity home in Cuba was part of the swift and radical transformations of the early 1960s, aimed at creating a more just and inclusive social order, first focusing on the most vulnerable and marginalized populations. Hence, the Agrarian Reform Law of 1959 gave deeds to 150,000 landless farmworkers, generating new economic opportunity; the 1960 Rural Medical Service sent recently graduated physicians to the country’s most remote regions, many of whose residents had never seen a doctor; and the 1961 Literacy Campaign (later lauded by UNESCO) sent over 120,000 young volunteers across the island, teaching 700,000 to read and write.[6]

Today, population health experts would say that these programs were aimed at tackling the “social determinants of health,” which they certainly were. A 1956–1957 University Catholic Association study of a representative sample of 1000 rural families had found only 11% of farmworker families had milk to drink; just 2% had eggs; 64% had no latrine; and 84% no place to bathe.[7] Over half the population was undernourished; just 10% of children received pediatric care, while 80% suffered from intestinal parasites; and the first cause of death for all ages was gastroenteritis. Maternal mortality was recorded as 138 per 100,000 live births and infant mortality as 34.8 to 70 per 1000 live births, both certainly underreported (even considering that newborn deaths were not counted in the first 24 hours after birth). Medical services were curative and concentrated in Havana; there was essentially no medical care in the countryside, with only one rural hospital.[8–10]

One rural hospital meant that women throughout the island faced the prospect of home delivery, mainly without skilled birth attendants, or trying to make it to a city hospital kilometers away—if they had the means. This partially explains the low percentage of in-hospital births (20%–60%, according to various authors) in Cuba before 1959.[11,12]

In 1961, noted physician Dr Celestino Álvarez Lajonchere was charged with obstetrical care within the newly unified public health system responsible for all medical services, provided free from this point forward. A main objective was to increase institutional births as a way to address obstetric complications and thus reduce both maternal and infant mortality. In his interviews with expectant mothers, they referred to distance from hospitals, poor roads and lack of transportation as the main reasons they delivered at home.[13]

This observation led to the creation of the first maternity home in 1962 in eastern Camagüey Province. The home was purposefully located near the province’s best-equipped maternity hospital to provide preterm care for apparently healthy pregnant women who nevertheless lived far away, so they could be easily transported to hospital for delivery.[11,14,15] Through 1969, as homes were established primarily in the rural and mountainous eastern provinces, geographic isolation was the main criterion for admission, although poor nutritional status and social conditions contributed to the decision.[16]

In that first period, 15 homes were set up in various provinces. Spacious, vacant houses were usually chosen, adapted to accommodate 15–20 pregnant women. The homes, resembling guest houses, included living and dining rooms (for activities and family visits), several bedrooms, bathrooms, kitchen and laundry, as well as areas that could be converted into nurses’ stations and basic exam rooms. Administrators were often midwives (a profession that later disappeared with the training of obstetric nurses), with hospitals providing both budgets and other medical personnel who visited the homes regularly. The result was a relatively inexpensive way to provide care, monitoring and health education to the expectant mothers, as well as to reduce hospital bed occupancy.[16]

CHANGING CONDITIONS, MODELS, PROTOCOLS

Maternity home development in Cuba has been divided into three distinct periods: 1962–1969, 1970–1989 and 1990–2010, to which this essay adds a fourth: 2011–2017. Although the main goal has always been to improve care for pregnant women to ensure healthy mothers and newborns, various aspects of implementation developed with the health system itself.[17]

In the first period, described above, maternity homes functioned essentially as annexes to the hospitals they reported to, without independent budgets, and operated under the guidance of hospital medical staff. Health education of expectant mothers (including care of themselves and their newborns) was informal, recreational activities spontaneous, and meals responded to basic norms of healthy nutrition within limited means. The numbers of homes grew slowly, reaching 15 by 1969 and 24 by the beginning of the second period in 1970. By that year, women in remote areas also had greater access to medical care in general: in addition to improved roads, 53 rural hospitals had been built, and in 1971, the majority of doctors were no longer practicing in the capital, 42% in comparison with 65% in 1958.[18,19]

Over the next two periods, the maternity home concept was adopted and adapted on a national scale, the numbers of homes and beds expanded throughout the country, and more resources were assigned to these institutions. Admissions also grew.[20]

From 1970 to 1989, the numbers of homes and beds multiplied rapidly (the latter reaching 150 by 1989, 10 times the number 20 years earlier), and homes had been established in each risk factors that also considered social determinants and mental health. Among these were insufficient gestational weight gain, prior miscarriage, adolescent pregnancy, macrosomia, risk of low birth weight, anemia, preeclampsia, asthma, history of epilepsy, single women who faced family rejection, depression, stress, domestic violence, low socioeconomic status, and overcrowded or otherwise unhealthy living conditions.[21] In other words, geographic isolation became only one of many factors that could complicate delivery and put mother or infant at risk, and needed to be addressed. In addition to increasing institutional births, a finer point was put on this broader array of risk factors in order to reduce both infant and maternal mortality.

Embedded in this shift was the recognition that maternity homes were also needed in urban areas. In 1972, geographic isolation was the criterion for 1176 admissions, with only 5 the result of maternal–fetal risk factors; 10 years later, 809 admissions were geographic and 225 attributable to other risk factors.[3] In the 1980s, additional risk factors were added, such as jobs requiring heavy labor in agriculture.

At the same time, some of the original premises underwent changes: homes were relocated near community-based multispecialty polyclinics instead of hospitals, sometimes, in fact, far from hospitals; one home had as many as 120 beds, while others were closed, particularly ones that had been established near rural hospitals that no longer provided birthing services; and homes had their own budgets, which raised costs and increased personnel.[3] While most physicians assigned to the homes were still on hospital payrolls, maternity homes now had teams of nurses as well as administrative employees, dieticians, bookkeepers, cooks, housekeepers, launderers and gardeners.[21]

Care during this time was focused on both medical and social aspects, with regular obstetric visits interspersed with those by other specialists. In general, education was enhanced to include information on contraceptives, preparation for labor and delivery, and advice for pregnancy and newborn care, the latter focusing on aspects such as the importance of nursing, vaccination and diet. Noteworthy are two momentous initiatives launched in this period: in 1983, the National Maternal–Child Health Program was established by the Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP), providing both guidelines and benchmarks in this already prioritized sector of the health system. The same year, the Family Doctor-and-Nurse Program was piloted, and soon extended throughout the country, locating a family doctor and nurse in every Cuban neighborhood. These two taken together strengthened the primary health care system, already anchored in the community-based polyclinic, and improved organization of preventive, curative and rehabilitation services. Family doctor-and-nurse offices were handed the main responsibility for regular antenatal visits, well-baby checkups and vaccinations. Patients were also seen by polyclinic obstetricians and pediatricians.

The third period, 1990–2010, saw the fastest growth of homes (153 in 1990 to 336 in 2010), and admission criteria were once again expanded. A new modality was added to the already flexible schedule: that of day boarder—women would spend their days there, returning to their own homes at night. The main purpose was to ensure nutrition, three meals a day, especially for the growing number of expectant mothers with insufficient weight gain during pregnancy. This modality was critical during the 1990s, when the socialist bloc collapse and tighter US sanctions shrank the Cuban economy by some 35%, making food and other scarcities common. In particular, low birth weight rates—fueled by expectant mothers’ poor nutrition, causing intrauterine growth retardation—had begun to creep upward, a sure warning that an increase in infant mortality was not far behind. In 1990, Cuba’s low birth weight rate was 7.6%, steadily declining since 1978. But by 1995, after the worst years of the economic crisis, the rate stood at 7.9%.[22]

Many maternity homes had the cooperation of workplace lunchrooms or private farmers, who provided meals and produce free of charge, and novel ideas were implemented in some towns: in Cardenas, Matanzas Province, a restaurant was established catering solely to pregnant women and in other cities, nutrition centers attracted expectant mothers, among others.[3]

Late in this period, the Maternal–Child Health Program issued a series of methodological guides for maternity home aims, organization, evaluation and record-keeping, which are still in place today. By 2007, criteria for admission included multiple pregnancy (>20 weeks), risk of premature birth, fetal growth retardation, maternal age >35 years, anemia, vaginal sepsis, high blood pressure (even if controlled), insufficient weight gain, adolescence, epilepsy, low placental insertion, geographic isolation and social risk (any living conditions that might endanger mother or newborn health). Management of each of these criteria was addressed in the methodological guides, which were quite extensive. They included everything from a questionnaire to ascertain satisfaction with services received, to differential attention to adolescents (since teen pregnancy, although relatively rare, is considered a public health problem) and specific dietary instructions for different recommended levels of calorie intake.[21–23]

The fourth period (2011–2017) coincides with a series of transformations in Cuba’s health system as a whole, aiming for both more efficient use of scarce resources and improved quality of care. These transformations were summarized in three dimensions: service reorganization, consolidation and regionalization. In essence, these initiatives were designed to reduce waste and bureaucracy, concentrate high-tech equipment where most often utilized, and locate services and facilities according to need (as defined by use).[24]

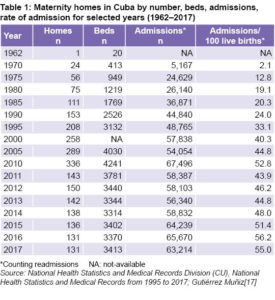

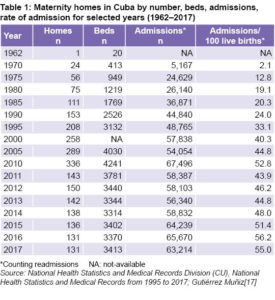

This process had specific consequences for the maternity home program: admissions had decreased from 2002 to 2006, when they began increasing once again. But with the 2010 transformations, according to Iñiguez, “the care pregnant women receive in maternity homes is being reorganized based on occupation rate (pregnant women per maternity home), distance to polyclinics with beds, and rapid access to the corresponding obstetrical–gynecological hospital. A reduction of maternity homes is expected, accompanied by a downsizing of maternity care organizational structures.” She noted that consolidation of homes had already begun in some provinces.[25] As a result, the number of homes went from 336 in 2010 to 131 in 2017 (a 61.1% reduction); the number of beds was not cut as drastically, from 4241 to 3413 (a 20.5% reduction); and admissions remained fairly high (67,496 in 2010 and 63,214 in 2017, a reduction of just 6.3%) (Table 1).

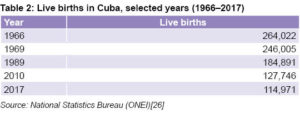

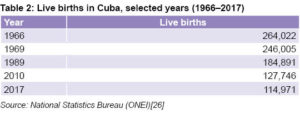

While the numbers of live births decreased during the same period (from 127,746 to 114,971, see Table 2), the admission rate per 100 live births actually increased in 2010–2017, from 52.8 to 55. This, along with the reduction in numbers of homes, leaves questions unanswered as to the balance between regionalization and access to needed care, both in terms of increased distance of the homes from women requiring them and in terms of how length of stay may or may not be affected by the new norms—both important to overall health results.

see Table 2), the admission rate per 100 live births actually increased in 2010–2017, from 52.8 to 55. This, along with the reduction in numbers of homes, leaves questions unanswered as to the balance between regionalization and access to needed care, both in terms of increased distance of the homes from women requiring them and in terms of how length of stay may or may not be affected by the new norms—both important to overall health results.

RESULTS & OBSERVATIONS

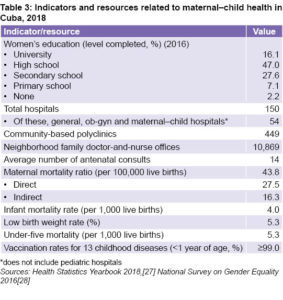

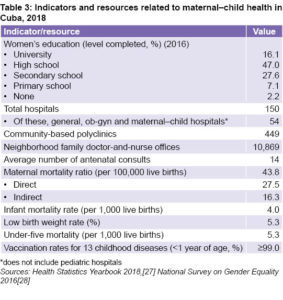

Cuba’s improvements in maternal–child health are multifactorial—from women’s educational levels and other social determinants, to quality of OB/GYN and pediatric care, the national Maternal–Child Health Program’s development and implementation, and in particular the strength gained in primary health care services as pillars of the country’s universal health care system (Table 3). It is within the primary care context that maternity homes play a role, and where their results and influence can be described and evaluated.

Evolution  tailored to needs Cuba’s maternity homes have offered admission to pregnant women at risk due to different factors in different contexts at different times. The institution has shown great flexibility in addressing these needs in terms of location, admission criteria, main activities and personnel. Thus, in the first period (1962–1969), when the main aim was to increase institutional deliveries for geographically isolated women, the homes contributed to more in-hospital births, a percentage that has dramatically increased, reaching 85% by 1968, and 99.9% in 2018.[21,27] A collateral result was a marked increase in registered births, 100% in 2017.[29] Access to hospitals was also aided by extension of free health services throughout the country as well as building of rural hospitals, as noted above. This was complemented by construction of 27,650 kilometers of new roads between 1959 and 1980. In addition, over time, a greater share of the population was concentrated in urban areas (77% by 2017).[30]

tailored to needs Cuba’s maternity homes have offered admission to pregnant women at risk due to different factors in different contexts at different times. The institution has shown great flexibility in addressing these needs in terms of location, admission criteria, main activities and personnel. Thus, in the first period (1962–1969), when the main aim was to increase institutional deliveries for geographically isolated women, the homes contributed to more in-hospital births, a percentage that has dramatically increased, reaching 85% by 1968, and 99.9% in 2018.[21,27] A collateral result was a marked increase in registered births, 100% in 2017.[29] Access to hospitals was also aided by extension of free health services throughout the country as well as building of rural hospitals, as noted above. This was complemented by construction of 27,650 kilometers of new roads between 1959 and 1980. In addition, over time, a greater share of the population was concentrated in urban areas (77% by 2017).[30]

When the economic crisis of the 1990s moved the needle upward on low birthweight rates, the homes’ nutritional supplements (assisted by cooperating workplaces and farmers) became a prime objective. Later studies in both urban and rural Cuban settings reveal that maternity homes have played a positive role in gestational weight gain and improved nutritional status, and hence undoubtedly were a factor in bringing down rates of low birth weight (and continued reduction of infant mortality related to this factor).[31–33] For example, in a home in Havana’s Cerro Municipality, 71 expectant mothers were studied, most admitted because of insufficient weight gain and 36.9% with anemia; both these factors showed statistically significant improvements, and 69 infants (97.2%) were born with normal birth weight (≥2500 g).[31] This result is consistent with an international review of 36 antenatal interventions, showing that nutritional supplements during pregnancy are one of the few effective ways to address impaired fetal growth.[34]

The educational level of Cuban women (Table 3), as everywhere, is a factor in maternal–child health. Universal education, free through university, has meant ever greater ability of women to understand and implement actions necessary for their own and their children’s health. This has assisted health professionals in their maternity-home classes on healthy nutrition, exercise, infant care and medical attention. Certainly, the fact that vaccination rates for infants under one year are over 99% is one result of combined efforts by such health professionals and the mothers themselves, who are most often the ones to take their children to well-baby doctor visits.

Costs, benefits and satisfaction Although no literature specific to Cuba attests to reduction of hospital stays and associated costs due to use of the more economical maternity homes, the institution’s general contribution in this regard is recognized internationally.[4]

The more recent reduction in homes and beds must be assessed in light of maintaining equitable access to quality services, particularly related to issues of transportation. In The 2016 National Survey on Gender Equality, difficulty with transportation was rated by both women and men as one of the three most pressing problems faced, particularly stressful in Havana.[28]

The vast majority of Cuban women express satisfaction with antenatal care in general, with UNICEF data showing 97.8% receiving at least four antenatal consults, with a national average of 14. A 2003 study of pregnant women’s attitudes in four developing countries noted that “[Cuban] women expressed a high level of satisfaction about the information they receive during pregnancy. Still, they might be lacking information on how to deal with the emotional and psychological changes occurring during pregnancy.”[35] It is important to recall that maternity home admission is not mandatory, and depends both on a woman’s risk perception and her satisfaction with care received, since she can leave at any time.[36] It would be important to conduct research into the level of satisfaction with maternity homes in general, based on the questionnaires that women and their families fill out upon discharge.[22]

Maternity homes’ relation to infant and maternal mortality Both infant and maternal mortality are indicators influenced by multiple factors. In Cuba, where infant mortality has been under 5 per 1000 live births for several years, maternal mortality remains a concern. While steady and sometimes sharp declines were registered from the early 1960s through even the most difficult years of the 1990s,[37] it has since risen slightly, reaching a plateau: maternal mortality ratio (MMR, direct and indirect deaths per 100,000 live births) was 41.9 in 2016, 39.1 in 2017, and 43.8 in 2018.[27]

It is unclear whether maternity homes have greater potential to contribute to lowering MMR at this point, since most causes of direct maternal deaths in recent years are related to postpartum complications, including infections; and hypertension accounted for 3.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2018.[27] Focusing more maternity home educational efforts on signs and symptoms related to these causes could be one area worth greater emphasis, as well as exploring paying greater attention to emotional and psychological factors that may contribute to MMR.

Anemia remains a problem for both maternal and newborn health, and excess weight gain and obesity also are on the rise. Maternity homes have a role to play in continuing to address nutritional issues. According to UNICEF, in 2014, 30.9% of pregnant women faced weight problems: 16.3% underweight, 9.8% overweight and 4.7% obese; while over the course of their pregnancies, 71.5% experienced normal weight gain.[38] In addition, one in five pregnant women suffer mild iron-deficiency anemia in their third trimester.[39] However, according to the same UNICEF survey, of the 31% of pregnant women who are prescribed iron supplements, 93% take their medicines. Since so many women are admitted to a maternity home for at least some time during their pregnancies, monitoring of both nutrition and weight gain can make an important contribution to reduce related risk. It may be worth reviewing both exercise and nutritional regimens for overweight and obese women.

Gender and equity lenses While women’s sexual and reproductive rights are explicitly guaranteed under Cuba’s Constitution and legal framework, and these rights are further explored and explained in maternity home educational sessions, it is also true that gender inequality has an effect as couples prepare for parenthood.[21] This has several implications for maternity homes: the first is the continued need for these homes, to relieve stress on pregnant women resulting from their greater burden of household responsibilities, estimated at 14 hours more than men weekly.[28] Second, through the Responsible Parenthood Program, initiated by MINSAP in collaboration with UNICEF,[40] prospective fathers are encouraged to play a greater role in pregnancy, birthing and care for their newborn child. Male partners are asked to attend psycho–physical classes at the maternity homes, preparing for participation when the time comes for delivery, but percentages of men who actually do so are unkown. More attention could be given to this aspect to further support and empower women during and after pregnancy.

A final word Cuban maternity homes were set up first and foremost to improve the health of women, mothers and children in the context of the drive for universal health within limited resources. Key to the continued success and relevance of these institutions will be the degree to which health authorities respond to needs expressed by pregnant women themselves, as participants in the construction of health, and in so doing propose new modifications to the maternity home model that extend equity and improve this vulnerable subpopulation’s health and well-being.

References

- Fescina RH, DeMucio B, Durán P, Martínez G. El hogar materno: descripción y propuesta para su instalación. Publicación Científica 1585. 2nd ed. Montevideo: CLAP/SMR; 2011. Spanish.

- Rojas Ochoa F. Acerca de la historia de la protección de la salud de la población. In: Rojas Ochoa F, Silva Hernández D, editors. Salud Pública/Medicina Social. Havana: Editorial Ciencias Médicas; 2009. p. 5–8. Spanish.

- Antecedentes de los hogares maternos. Cuad Hist Salud Pública [Internet]. 2007 Jun [cited 2019 Sep 9];(101). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0045-91782007000100005&lng=es. Spanish.

- Pan American Health Organization; Centro Latinoamericano de Perinatología / Salud de la Mujer y Reproductiva – CLAP/SMR. Hogar Materno. Descripción y propuesta para su instalación. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; World Health Organization; 2011 Aug 24. 12 p. Spanish.

- Castell Moreno J. Hogares Maternos. In: 17 Años de Ginecología y Neonatología. Havana: Imprenta Camilo Cienfuegos; 1976. p. 59–63. Spanish.

- Pérez-Cruz FJ. La Campaña Nacional de Alfabetización en Cuba. VARONA Rev Cient Metodol [Internet]. 2011 Jul–Dec [cited 2019 Jan 10];53. Available from: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3606/360635575pdf. Spanish.

- Agrupación Católica Universitaria. Encuesta de los trabajadores rurales 1956–1957. Rev Cubana Salud Pública. 2014;40(3). Spanish.

- De la Torre E, López C, Márquez M, Gutiérrez JA, Rojas Ochoa F. Salud Para Todos: Sí Es Posible. Havana: Cuban Society of Public Health (CU); 2004. p. 42–3. Spanish.

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Report on Cuba. Findings and recommendations of a technical mission («Informe Truslow»). Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press; 1951.

- Riverón Corteguera RL. Estrategias para reducir la mortalidad infantil. Rev Cubana Pediatr. 2000 Jul–Sep;72(3):147–64. Spanish.

- Ramos Domínguez BN, Valdés Llanes E, Hadad Hadad J. Hogares Maternos en Cuba: su evolución y eficiencia. Rev Cubana Salud Pública. 1991 Jan–Jun;17(1):4–14. Spanish.

- La contribución de los hogares maternos de Cuba a la salud materno-infantil. Cuad Hist Salud Pública. 2007 Jan–Jun;(101). Spanish.

- Delgado García G. Los hogares maternos: su fundación en Cuba y objetivos propuestos desde su creación. Cuad Hist Salud Pública. 2004 Jan–Jun;(95). Spanish.

- Gil de Lamadrid J. Hogar de maternidad. Casa Bonita. Bohemia. 1964;56(21):22–5. Spanish.

- Álvarez Lajonchere C. Antecedentes, evolución y desarrollo perspectivo de la ginecobstetricia en Cuba. Informe presentado al Consejo de Dirección del Viceministro de Asistencia Médica y Social. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 1973 Apr. Spanish.

- Gutiérrez Muñiz JA, Bacallao Gallestey J, Berdasco Gómez A. Contribución de los hogares maternos de Cuba a la maternidad sin riesgo. Havana: [publisher unknown]; 1990. Spanish.

- Gutiérrez Muñiz JA, Delgado García G. Los Hogares Maternos de Cuba. Cuad Hist Salud Pública [Internet]. 2007 Jan–Jun [cited 2019 Jan 1];(101). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0045-91782007000100001&lng=es. Spanish.

- Delgado García G. El Servicio Médico Rural en Cuba: antecedentes y desarrollo histórico. Rev Cubana Admin Salud; 1986 Apr–Jun;12(2):169–75. Spanish.

- Roemer MI. Cuban Health Services and Resources. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 1976.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU). Libro Registro de Hogares Maternos. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2012. Spanish.

- González López R, Díaz Bernal Z. Hogares Maternos: Experiencia cubana hacia transversalización de género y etnicidad en salud [Internet]. Havana: ECIMED; 2015 [cited 2019 Jul 7]. 39 p. Available from: http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/33898/9789592129771_spa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Spanish.

- Bonet López N, Choonara I. Can we reduce the number of low-birth-weight babies? The Cuban experience. Neonatology. 2009;95(3):193–7.

- Santana Espinosa MC, Ortega Blanco M, Cabezas Cruz E. Metodología para una acción integral en Hogares Maternos. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2006. Spanish.

- Ministry of de Public Health (CU). Transformaciones necesarias en el Sistema de Salud Pública. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2010. Spanish.

- Iñiguez L. Overview of evolving changes in Cuba’s health services [reprint]. MEDICC Rev. 2013 Apr;15(2):45–51.

- National Statistics Bureau (CU). Anuario Demográfico de Cuba 2018 [Internet]. Havana: National Statistics Bureau (CU); 2019 Jun [cited 2019 Jul 7]. 143 p. Available from: http://www.onei.cu/anuariodemografico2018.htm. Spanish.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division. Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2018 [Internet]. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 7]. Available from: http://files.sld.cu/bvscuba/files/2019/04/Anuario-Electr%C3%B3nico-Espa%C3%B1ol-2018-ed-2019.pdf. Spanish.

- Center for Women’s Studies (CU); Center for Population and Development Studies (CU). Encuesta Nacional sobre Igualdad de Género 2016 [Internet]. Havana: Center for Women’s Studies (CU); Center for Population and Development Studies (CU); 2018 Nov [cited 2019 Apr 27]. Available from: http://www.one.cu/publicaciones/cepde/ENIG2016/Publicaci%C3%B3n%20completa%20ENIG%202016.pdf. Spanish.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division CU. Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2017 [Internet]. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 7]. Available from: http://files.sld.cu/dne/files/2018/04/Anuario-Electronico-Espa%C3%B1ol-2017-ed-2018.pdf. Spanish.

- Comité Estatal de Estadísticas: Cuba: Desarrollo Económico y Social 1959–1980. Havana: Editorial Estadísticas; 1981. Spanish.

- Calzadilla Cámbara A. Impacto del Internamiento en un hogar materno sobre el estado nutricional de la embarazada. Rev Cubana Aliment Nutr. 2013 Jan–Jun;23(1):139–45. Spanish.

- Rubio Rodríguez M, Aranda Carrión M. Logros del hogar materno en la recuperación de peso de las gestantes. Rev Cubana Enfermer. 2000 May–Aug;16(2):73–7. Spanish.

- Boloy Crezco N, Lucas Ortíz F, Corrales Ortíz A. Caracterización de las embarazadas bajo peso ingresadas en un hogar materno. Rev Cubana Enferm. 2004 Sep–Dec;20(3). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-03192004000300002&lng=es&nrm=iso. Spanish.

- Gülmezoglu M, de Onis M, Villar J. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent or treat impaired fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1997 Feb;52(2):139–49.

- Nigenda G, Langer A, Kuchaisit C, Romero M, Rojas G, Al-Osmy M, et al. Women’s opinions on antenatal care in developing countries: results of a study in Cuba, Thailand, Saudi Arabia and Argentina. BMC Public Health. 2003 May 20;3:17.

- Bragg M, R Salke T, Cotton CP, Jones DA. No child or mother left behind; implications for the US from Cuba’s maternity homes. Health Promot Perspect. 2012 Jul 1;2(1):9–19.

- Cabezas Cruz E. Evolución de la mortalidad materna en Cuba. [Internet]. Rev Cubana Salud Pública. 2006 [cited 2019 Jan 10];32(1):32–6. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34662006000100005&lng=es. Spanish.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Encuesta de Indicadores Múltiples por Conglomerados 2014. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2015 Jul. 235 p. Spanish.

- Santana Espinosa MC, Esquivel Lauzurique M, Herrera Alcázar VR, Castro Pacheco BL, Machado Lubián MC, Cintra Cala D, et al. Atención a la salud materno infantil en Cuba: logros y desafíos. Informe Especial 42 [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 10]. 9 p. Available from: http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/34900/v42e272018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Spanish.

- López Fersser M. Padre desde el principio: promoviendo el desarrollo de la primera infancia en Cuba. Havana: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) [Internet]; 2017 Aug 2 [cited 2019 Aug 7]; [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/es/historias/padre-desarrollo-primera-infancia-cuba. Spanish.

THE AUTHOR

Francisco Rojas-Ochoa (rojaso@infomed.sld.cu), physician specializing in health administration with a doctorate in health sciences. Distinguished professor and researcher at the National School of Public Health and Distinguished Member of the Cuban Academy of Sciences, Havana, Cuba.

Submitted: March 07, 2019 Approved: August 29, 2019 Disclosures: The author founded Cuba’s first maternity home in 1962 in Camagüey.