This May, when the earthquake’s death toll passed 60,000 and another 30,000 poured into hospitals in Southwest China’s Sichuan province, Cuba responded to the call for medical assistance with a team of 35 health professionals. At their helm: Dr José Jorge Rodríguez, who a rrived on May 23, less than a week after our interview in Havana. At press time, the team was working at th e province’s larg est public hospital, treating victims of the massive quake and its after- shocks.

Sichuan is half a world away from the Faustino Pérez Provincial Teaching Hospital in Matanzas, Cuba, where Dr Rodríguez is on staff, but being far from home is nothing new for this Cuban surgeon. Since the Henry Reeve Team of Medical Specialists in Disasters & Epidemics was founded three years ago, it’s hard to tell exactly where you will find him. In that time, he has accumulated a world of disaster experience: from treating earthquake survivors on the Pacific island of Java, to overseeing his team as they set up field hospitals in quake-shaken Peru; from an operating room in a remote Himalayan village to his latest assignment in this public hospital in China.

Originally established in September 2005 in response to Hurricane Katrina, the Henry Reeve Team is named after a Brooklyn-born hero of Cuba’s independence wars in the 1800s. (See: Gorry C. Cuban Disaster Doctors in Guatemala, Pakistan. MEDICC Review. 2005; 7(9):11-12 and Gorry C. Cuba’s Response to Katrina Disaster. MEDICC Review. 2005; 7(8):31-32.) Although the US administration rejected the Cuban offer of assistance, the Team has been requested by seven disaster-stricken countries since then -and Dr Rodríguez has been called into action four times himself, directing field hospitals in Pakistan and Indonesia, and most recently coordinating the contingents sent to Peru and China.

Dr Rodríguez (r.) with Cuban and Chinese colleagues in Sichuan public hospital.

MEDICC Review: Although Cuba has been sending disaster response teams abroad for years before the Henry Reeve, it’s my understanding there was no experience operating field hospitals. Yet, in Pakistan, the Cubans had to set up and run 32. What does it take to set up one of these hospitals.

José Rodríguez: Before Pakistan, we had no experience in setting up and running field hospitals. Many other countries had this experience, but not Cuba. Pakistan was a first for Cuba, and it was a school for all of us.

When we got to Peru, we already had two earthquake-response experiences under our belts. We were the first [international medical team] to land in the disaster zone, three days after the quake. When we arrived, there was still a cloud of dust in the air. By that time, our ambassador and the Mayor of Pisco had identified two suitable sites for field hospitals in Pisco. What is a suitable site. You need a large space with access to water and either a waste disposal system or the possibility of building latrines. With these basics in place, then you can set up electrical generators and water purification and storage systems, and you’re up and running. Without water and electricity, you can’t work.

Our goal is always to have the operating room and intensive care units functioning within 24 hours of arrival, so we can begin operating on the first cases. We try to have the whole hospital – the emergency room, patient wards, examining rooms, clinical laboratory, and x-ray – up and running within 72 hours.

Everyone in the team helps set up the hospital, doctors and hospital directors included. Of course we are exhausted the next day when we begin operating, but somehow we make it work.

In Pisco, we set up our hospitals in two parks on the opposite extremes of the city, about 15 minutes apart by car. Both were locat ed near large refugee camps sheltering several thousand people. Other international medical teams from Chile, the United States, and Pakistan arrived a few days later, and set up hospitals in the neighboring cites of Chincha and Ica.

We succeeded in having operating theaters ready within 24 hours after arriving on site. The surgical team began operating while the others were still setting up the rest of the hospital. Within 48 hours, we had housing set up for our personnel, and on the third day we opened the hospital at 7:30am. Our team saw 1,740 patients that first day.

MEDICC Review: One thing that disasters have in common is that they often disable the local health infrastructure, making it difficult for survivors to get help. We’ve seen the photos of the Henry Reeve members with their backpacks heading out to affected communities. Can you tell us a little more about the role of these outreach teams in disaster response?

Cuban physician in the field after Pakistan earthquake, 2005.

José Rodríguez: Some of the people affected are able to come to the hospital, but there are others who aren’t able to make it, either because of the severity of their injuries, or because of the distance. Maybe they don’t have transportation, or the resources to pay for transportation. When they can’t come to us, we go to them.

In Peru, we depended on the civil defense and the military to guide us to the most damaged areas. With their help, we worked in 176 districts of the country. When we arrived, we started seeing patients right away. While the medical aid donated by Cuba was still being unloaded from the cargo planes at the Pisco Airport, we started treating patients in the immediate area. Later, after the two field hospitals were up and running, we continued to go out into the field to care for survivors who couldn’t make it to the hospitals.

MEDICC Review: Do you tailor the composition of the team to the nature of the disaster. Or do the same kinds of specialists go to each place?

José Rodríguez: To some degree, the composition of the teams is standard. There are ten specialties that are the core of every team: surgery, orthopedics, dermatology, emergency medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, pediatrics, anesthesiology, radiology, epidemiology, and critical care. Beyond these, the composition of the team depends on the specific situation, the type of disaster, and at what stage post-disaster we are arriving.

As time passes after the initial catastrophe, the composition of the team also changes. Luckily in Peru, the Pisco airport was not destroyed, and many people with serious injuries were evacuated to hospitals in Lima immediately after the quake. After their discharge from the hospital in Lima, they returned home to areas where there was no place for them to continue treatment or begin rehabilitation. Pisco’s hospital had been destroyed. Our team ended up staying in the country much longer than we had originally planned to fill this gap. A month after we arrived, we were joined by a team of physical therapists from Cuba who helped in the rehabilitation of these patients.

MEDICC Review: After the team’s experiences in Pakistan and Indonesia, the curriculum of the Henry Reeve’s training program for new members was revised. I understand that now one of the first activities is a question-and-answer session with veteran members, to pass on their experiences. What is the process for learning from the team’s experiences abroad. How does the team use these lessons.

José Rodríguez: After each mission, the Henry Reeve Team directors also sit down and reflect on the experience. We ask our-selves, what did we need that we didn’t have to get the job done. Medications, personnel, logistical problems: everything goes into a report that we call “Lessons Learned”.

One of the lessons we learned in Peru was the importance of having psychologists and psychiatrists as part of our team when we go to a Spanish speaking country. In Indonesia and Pakistan we didn’t bring them because of the language barrier, but when we arrived in Peru, we found that we really needed them.

Acute psychological traumas after an earthquake of that magnitude can last up to six months after the event. When you ask someone about their experience, they will tell you that they saw the ground move under them like a wave and when it stopped they had lost everything. Not just materials things, but their families and loved ones. Some psychologists will tell you that every aftershock is a new trauma for an earthquake survivor. The psychological traumas we saw were so severe that psychiatrists were just as important part of the team as the emergency medicine specialists.

Youngster, mom and Cuban pediatrician in Sichuan hotimespital, June, 2008.

In Peru, Civil Defense asked us to come to a meeting for all the groups that had been part of the relief effort, to evaluate it and make improvements for the future. Before leaving, we were also asked to teach a course on disaster preparedness and response, so we designed 25 workshops to share what we had learned in Pakistan, Indonesia, and Peru. They were most interested in how to set up and run field hospitals. At the time, Peru had no experience with field hospitals. Our two field hospitals were donated to the country, and later they invested in their own field hospital modules, which are not tents like ours, but containers that can be moved by truck. They are very comfortable, with heating and airconditioning, and most importantly, they make it easy to maintain sterile conditions. Peru is vulnerable to many natural disasters, not only earthquakes, but torrential rains, landslides, and mudslides, and these mobile units can be set up anywhere in the country. Peru now has more tools to face future disasters.

MEDICC Review: And can you give us a picture of what it’s like personally, being part of the Henry Reeve Team?

José Rodríguez: When you’re part of this team, you’re always on call, ready to go. The phone rings, and we’re off. I’d heard about the earthquake in Peru on the news but didn’t even know yet whether Cuba would send doctors. I was in the middle of a surgery at the hospital when my supervisor came in and asked me if I was almost done. She said she’d come to take over my shift because they needed me in Peru. I finished the surgery, went home to tell my wife and daughter, and when I got there, a car was already waiting to take me to the airport.

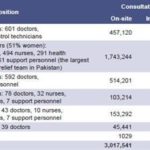

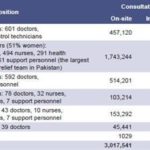

The Henry Reeve Team, 2005-2008

MEDICC Review, Summer 2008, Vol 10, No 3