ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION In 19th century colonial Cuba, Boards of Health (Juntas de Sanidad) were created to administer public health, in tandem with and later replacing the older Royal Protomedicato Court (Real Tribunal de Protomedicato). Development of the Board of Health in the northeastern city of Holguín reflected local historical processes, as well as class relations and social issues characteristic of this period. Among the highlights of the Board’s activities were epidemic control during cholera and smallpox outbreaks, monitoring the city’s sanitary conditions, and support for charitable work. Studying the history of such epidemiological surveillance activities may benefit design and implementation of related current research and prevention/control campaigns.

OBJECTIVE Describe the development of the 19th century Board of Health in the city of Holguín.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION The research was conducted through a critical analysis of primary sources contained in the Historical Archives of (today’s) Holguín Province, specifically relevant documents from the regional and city government (Fondo Tenencia de Gobierno y Ayuntamiento) and town council (Cabildo). Cuban and international scientific publications were also consulted.

DEVELOPMENT The Board of Health was the main institution conducting health and hygiene control and charitable activities in the city of Holguín during the 19th century. It was created mainly to take preventive measures against diseases affecting the population, an effort it undertook with support from the Urban Health Police. Its efforts to confront smallpox and cholera epidemics greatly helped to reduce the toll of these diseases on the population, albeit not sufficiently to prevent their reccurrence. Beginning in the 1870s, weakened government support eroded the Board’s position, and health-related measures were implemented mainly by the Board of Charity, which focused on matters concerning the city’s Civil Hospital.

CONCLUSIONS Although established in 1820, Holguín’s Board of Health carried out preventive actions most actively from 1850 to 1865, with support from the Urban Health Police. Its gradual disappearance from the health policy arena beginning in the 1870s reflects its failure as an institution, in large part due to weak government support.

KEYWORDS Board of Health, prevention, epidemics, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

Boards of Health (Juntas de Sanidad) were institutions created in Spain in the early 18th century to organize measures to combat the epidemics that plagued the country at the time. The Supreme Board, a judicial administrative body established in 1720, centralized Spanish health policy. Although it collaborated with other institutions such as the Royal Protomedicato Court (Real Tribunal del Protomedicato), the Supreme Board relied on provincial and local boards to ensure strict compliance with its policies. In addition to ensuring passage of laws and measures to protect population health, the Board’s influence in the 18th century extended to other areas all the way from shelters for the poor, sick and aged to medical publications.[1]

Early 19th century Cuba was shaped by important economic transformations such as development of the sugar industry, but also by political and social changes. An increase in the demand for slaves on the island and Spain’s neglect of the education and health sectors had major social impacts.[2] In this context, the colony’s public health measures fell short in the preventive control of diseases and public education in hygiene. Each of these developments manifested differently in different regions of the country, depending on their economic activities, local government policies and the general conditions in each location.

IMPORTANCE The history of health and hygiene surveillance in Cuban public health adds meaningful knowledge relevant to current health promotion campaigns and research on more recent disease trends and outbreaks, including those of dengue and cholera.

Boards of Health were created in Cuba in the early 19th century to carry out preventive actions. Initially, they performed this function jointly with the Royal Protomedicato Court, until the latter was dissolved in 1833 during the island’s first cholera epidemic. The work of the Boards of Health was essential in the fight against cholera, smallpox and yellow fever epidemics and facilitated health surveillance on the island during the colonial period. Its Superior Board was located in the Cuban capital of Havana, with subordinate boards in provincial and municipal capitals. This topic has been researched by several health historians in Cuba, including Gregorio García Delgado,[3] Enrique Beldarrain Chaple[4] and Gabriel José Toledo Curbelo.[5] Holguín city is located in northeastern Cuba. Its main 19th century health-related achievement was the creation in 1820 of the city’s Board of Health.

New outbreaks of dengue in Cuba since 1997,[6] as well as cholera in 2012 and 2013[7] demonstrate the ongoing importance of surveillance of infectious disease threats, particularly when effective vaccines may still be lacking. Studying the history of such epidemiological surveillance activities may benefit design and implementation of related current research and prevention/control campaigns.

This study is one of the first to research the development of the Board of Health’s prevention and control work in 19th century Holguín. (NOTE: unless otherwise indicated, Holguín hereafter refers to the city, not the province of the same name, established in 1976). It aims to describe the institution’s antecedents and its evolution during that period. The Board’s development reflects local historical processes, class relations and social problems of the era. Local historiography includes several works from this period partially related to this topic, such as those by José García Castañeda[8] and Adisney Campos,[9] although they do not detail the Board of Health’s work.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

To interpret the available sources, the authors applied critical, analytical and hermeneutic approaches to primary sources from the regional and city government (Fondo Tenencia de Gobierno y Ayuntamiento) and town council (Cabildo) historical archives of (today’s) Holguín Province. These contain the minutes of Board of Health and town council meetings. A literature review was also conducted of publications, both Cuban and non-Cuban authors.

DEVELOPMENT

Historical Antecedents of the Boards of Health Early civilizations suffered greatly from ignorance of the causes of diseases and were thus ill-equipped to protect communities from them, leaving populations exposed to infectious disease epidemics in particular. With the development of science, more policies were devised to successfully combat problems of health and hygiene. In 18th century Europe, studies were conducted using a social approach to medicine in order to improve the structure and function of existing health institutions.[10,11]

The Royal Protomedicato Court, founded in the 15th century, was the first institution created to organize public health in Spain, although it was not integrated into the country’s health surveillance system until 1752.[10] In 1780, it was subdivided into three new boards—Medicine, Surgery and Pharmacy—which would continue to operate under the Protomedicato until its final dissolution in 1833.[12,13]

The Urban Health Police, an institution established in Europe during the 18th century and operating throughout the 19th century, had its greatest impact in Western Europe. Its mission consisted of health surveillance and control, as set forth in the work of German physicist and hygienist Johann Peter Frank,[14] who proposed a set of actions aimed at protecting pregnant women, controlling epidemics and organizing hospitals and shelters for the poor, sick and aged. In Spain, the works of Valentín de Foronda, Vicente Mitjavila and Tomás Valeriola were noteworthy. They contained regulations aimed at maintaining sanitary control in cities and towns but did not take into account the social causes linked to epidemics.[15–17]

From 1832 to 1833, the Iberian peninsula and its colonies suffered a cholera epidemic that in Spain alone affected 449,264 people, of whom 102,511 died. This led to the creation of another important institution, the Central Board of Charity, to facilitate cooperation between government and religious authorities to confront the epidemic and supervise handling of donations, alms, budgets and charitable facilities such as hospitals and shelters.[17]

The Supreme Board of Health, created in Spain in 1720 in response to an outbreak of plague in Marseille, France, remained in operation until 1847. It was the country’s main institution dedicated to managing health policy, and established protocols to follow during epidemics such as plague and yellow fever. It was also charged with control and surveillance of ports, pharmacies, hygiene in prisons and shelters, and management and supervision of scientific research. Concerning the latter, the Board provided guidance to physicians studying contagious diseases and the best practices known at the time to treat and manage them.[1,11]

In Latin America, Boards of Health were established early in the 19th century and functioned similarly to those in the metropole. However, Spain’s centralized governance of its American colonies––which triggered the region’s independence movements in the early 1820s––also hindered the functioning of the Boards of Health. This dysfunction was exacerbated by local colonial governments’ disregard for sanitation, as evidenced in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (today Mexico), where problems such as poverty and precarious sanitation facilitated the spread of epidemics in its growing cities.[18] Cuban independence leader José Martí identified such problems as the main cause of disease and death in the American colonies, and referred to the importance of applying proper sanitation policies, noting: The true medicine is not that which cures, but that which prevents: hygiene is the true medicine. [19]

With the culmination in 1826 of the Latin American struggles for independence in South America and the final recognition by the Spanish government of the status of independent republics in 1836, Boards of Health ceased to exist as such and were replaced by similar institutions responding to the interests of the new republics.[20,21] However, Spain maintained its colonial rule over Cuba until 1898, and thus the Boards of Health continued to operate with more or less effectiveness during the greater part of the 19th century.

Genesis of Boards of Health in Cuba The period of Spain’s conquest and colonization of the island began in 1492 with the arrival of Christopher Columbus on Cuban coasts. The indigenous population was decimated by the conquerors in a process that began in 1502. Nicolás de Ovando, the first Spanish governor of the island, was charged with promoting colonial expansion by allocating lands that would lead to formation of towns. Diego Velázquez, Ovando’s capitan and later governor, became a main player in this process when he founded five of the first seven towns—the last of them, Santiago de Cuba, in 1515. The towns, organized Spanish style, had as their main form of government the cabildo, a council led by the most powerful residents.[2,15]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Cuba’s population was small compared to other American colonies, as the indigenous population had been all but wiped out and many Spaniards abandoned the island when they discovered there was no gold. Cattle ranching became the main economic activity, making for autonomous population centers, where trade in contraband goods also flourished. However, by the end of the 18th century, tobacco and sugar cultivation had gained more prominence.[2,15]

In colonial Cuba, the first public health institution established was the Royal Protomedicato Court of Havana in 1634, which Spain previously had instituted only in the Viceroyalties of Mexico and Peru.

In 1804, the Economic Society of Friends of the Land (Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País) promoted the founding of the Board of Vaccines, whose main goal was to immunize the island’s population. One of the most illustrious members of this Society was Dr Tomás Romay who was familiar with Edward Jenner‘s work. Dr Romay’s efforts were essential in the fight against smallpox. He played an important role in introducing the vaccine:[22] in cooperation with the Spanish mission that brought it to Cuba in 1804, he immediately vaccinated his own children as a first step. On July 30, 1804 the Central Board of Vaccines was established and Dr Romay appointed as secretary. He directed the Board for more than 30 years.[15,22]

Boards of Health were established in Cuba in 1807 to help the Royal Protomedicato Court carry out its functions. The Superior Board was located in Havana, several subordinate boards in the provincial capitals and local boards in the rest of the country’s municipalities. Their functions were similar to those of their counterparts in Spain; they were tasked with confronting diseases (specifically epidemics) afflicting the population, inspecting ships arriving at Cuban ports and monitoring sanitary conditions where food was sold. In 1848, following the closing of the Board of Vaccines, shortly after Dr Romay’s death, and due to organizational reasons, they took on implementation of vaccination programs.[15,22] Yet, constant political changes in early 19th century Spain made for instability in the organization’s functioning.[21]

The Holguín Board of Health: Creation and early years The city of Holguín is located in northeastern Cuba, about 774 km from Havana. On January 18, 1752, the Governor of Santiago de Cuba, Alonso de Arcos y Moreno, in compliance with a Royal Decree issued by Spain’s King Ferdinand VII, awarded the title of city to the settlement of Holguín and handed over a large portion of land, previously belonging to the territory of Bayamo. The municipality of Holguín thus gained 5084 useful hectares for agriculture and a 2.4 km2 area to be used for the city’s subsequent growth.[8] From an initial population of 1426, the jurisdiction grew nearly ten fold in the early years of the 19th century, to 12,695 inhabitants by 1820. In 1822, the construction of a major port facility in the village of Gibara, located 32 km north of the city on the Atlantic Ocean, provided an important stimulus for the region’s agriculture and livestock industry and led to extensive economic growth for Holguín.[23]

The 1820s were a period of economic prosperity, at least for some classes, under the administration of Lieutenant Governor Francisco de Zayas, who was responsible for major building projects, development of agriculture and commerce, and revitalization of Holguín’s Board of Health.[8] This was indeed the main health-related achievement in this period.

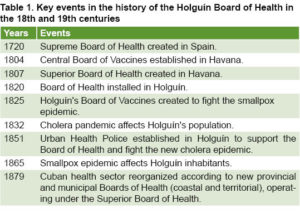

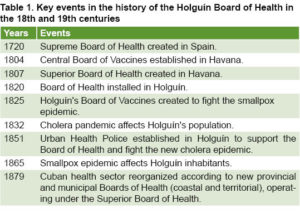

After some irregularities and changes, Holguín’s Board of Health was definitively installed on May 24, 1820. Presided over by Dr Juan Buch, the Board’s main function was monitoring and control of the city’s health and hygiene. Table 1 summarizes some of the main events associated with development of this institution in Holguín.[24]

Illustrative of the Board’s importance is a document dated May 17, 1815, detailed a meeting of Holguín’s town council members, who called on the city’s doctors to maintain strict control over diseases most affecting the jurisdiction, especially leprosy. This provision was in addition to the existing obligation for doctors to report illnesses in their populations by order of the Royal Protomedicato Court which, in turn, sent monthly reports to Spain.[25,26]

The Holguín Board of Health carried out activities similar to those of other municipal boards across Cuba, such as control of ports, hospitals, asylums and pharmacies. Another important function was sanitary control of food markets, especially meat sales, due to various cases of dysentery that appeared from consuming spoiled beef. The first agreement was (…) making the Constabulary and the slaughterhouse manager understand the need to ensure that spoiled meat…must not be admitted.[27]

The Holguín Board of Health carried out activities similar to those of other municipal boards across Cuba, such as control of ports, hospitals, asylums and pharmacies. Another important function was sanitary control of food markets, especially meat sales, due to various cases of dysentery that appeared from consuming spoiled beef. The first agreement was (…) making the Constabulary and the slaughterhouse manager understand the need to ensure that spoiled meat…must not be admitted.[27]

Repeated smallpox and cholera epidemics severely affected Holguín’s population in the 19th century, hindering the city’s economic and social development. Holguín implemented vaccination against smallpox with Dr Buch leading this effort. On April 6, 1825, Lieutenant Governor De Zayas presided over the establishment of the Board of Vaccines.[27]

However, Holguín Board of Health actions during the 1820s were few and limited to small-scale inspections in the city’s public establishments and sanitation. These are only recorded in town council minutes, since separate documentation of Board sessions did not begin until 1832. Francisco Javier Martínez poses one possible reason why the Board of Health actions are not discussed in other documents from the period:[28]

We are ignorant of the difficulties faced by [Cuba’s] Superior Board of Health between the Wars of Independence [in the Americas] and the restoration of absolutism in 1824 [in Spain], during which there were frequent and often contradictory changes in public health in Spain. The Superior Board of Health may have temporarily disappeared because, as a result of the dengue epidemic in the Antilles, Mexico, Colombia, Peru and the United States that affected Cuba in 1828, Captain General Francisco Vives decided to establish a new board that functioned as the higher body of health on the island until 1832.

Nevertheless, an 1832 document alludes to a report sent by the first heads of the Royal Treasury of Santiago de Cuba and Puerto Príncipe (charged with the colony’s fiscal records and tax collection),[29] expressing concern for strict control of ports. Specifically, the port of Gibara, a small village lacking a local government of its own, was deemed to require strict surveillance and control by the Holguín town council, lest it pose a danger to the city’s population. [30] Also noteworthy in the same report is a donation by the Count of Villanueva of 1636 pesos and 2 reales for the first month and 579 pesos and 7 reales for the remaining months during the epidemic duration to provide care for the infected poor, a fact underscoring the scarce resources available to the Board, which often needed to seek funds from private citizens.[31]

Martínez’s conjecture[28] may explain why, in the documents consulted, the first one referring to a Board of Health meeting is dated September 22, 1832 and relates to the cholera epidemic that struck several countries and eastern Cuba. This epidemic, which lasted until 1833, forced Spain to review its health policies and reorganize the structure of its main institutions. One of its actions was the creation of the Central Board of Charity, giving the colonial government a leading role in functions previously undertaken by the Catholic Church.

The Board of Charity arrived late in Holguín. During the epidemic of 1833, no documents were found drawing a connection between it and the Board of Health’s actions to fight the outbreak. The first document mentioning the Board of Charity’s work is dated 1861.[32,33] Unlike the Board of Vaccines, the Board of Charity did not have a close relationship with the Board of Health at the time. When its work became more systematic and organized beginning in the 1860s, the Board of Charity focused solely on managing the city’s Civilian Hospital and on collecting donations.[33]

Prevention and control efforts by Holguín’s Board of Health (1848–1865) The main topics discussed at Board of Health meetings reflected the priority of attention to diseases most affecting the population, especially those that reached epidemic proportions: thus, cholera and smallpox were the most frequent subjects in the first half of the 19th century.

The measures mandated by the territorial and Urban Health Police, approved on December 12, 1848 by the Superior Board of Health, were aimed at preventing the spread of cholera. These were endorsed in the Royal Order of December 26. In the same year, a regulation was approved establishing the economic and administrative structure of Cuba’s health sector.

Another example of the Board’s actions during epidemics is found in a document dated March 15, 1850, in response to a rabies outbreak in Holguín. Since a main cause was determined to be the many stray dogs roaming the streets, an order was issued to eliminate them. In addition, local leaders were required to ensure that only dogs needed for collecting or herding farm cattle would circulate, but these would also be eliminated if they showed any rabies symptoms.[34]

The creation of the Urban Health Police in Holguín in 1851 supported the Board of Health work by putting into practice many measures that, though officially adopted, had not been implemented with the priority required. It also bolstered the Board’s role by adding an executive branch to carry out its decisions. Although still dependent on the city’s town council, the new surveillance body gave the health institution greater freedom of action.[34]

Some of the first tasks entrusted to Holguín’s Urban Health Police were related to the appearance of a new cholera epidemic and were mentioned in the minutes of the Board of Health meeting of January 19, 1851. Police commissioners were ordered to abide by the following guidelines: defer cadaver burial for 16 hours after certification of death by an attending physician; publicly burn clothes and other belongings of deceased; provide 14 cots for the Charity Hospital and two stretchers, one for patient transfers to the hospital and the other for cadavers.[34]

Repeated outbreaks tested the Board’s level of organization and effectiveness. Cholera, in its variant known as Asiatic morbus, was a major public health problem in the Americas during the 19th century.[35] In Holguín, four periods were recorded in which, according to minutes of the town council and of the Board of Health, the disease appeared with greater strength: the first in 1832–1833, the second in 1851–1852 and the third and fourth in 1870 and 1883.

Local government and Board actions during the 1851–1852 epidemic were insufficient to stop one of the century’s most dangerous cholera outbreaks. This prompted a communication in January 1851, from the Santiago de Cuba Provincial Board of Health to the president of the Holguín Board. It argued for stepped-up efforts to address the epidemic, given 29 cholera deaths in Holguín, continued infection among civilian and military populations, and the ineffectiveness of control measures thus far. This included the requirement that every doctor submit a daily report to the Board of Health detailing cholera cases and their evolution, as well as a general report to the Provincial Board.[36]

Other tasks undertaken by Holguín’s Board of Health in 1851 related to management of garbage dumps in empty lots to control their harmful effects. The Urban Health Police was in charge of controlling improper disposal practices.[34] This problem was not unique to Holguín. In Havana, poor sanitary conditions spread alongside the growth and development of the urban nucleus. Enrique Beldarrain also mentions contamination of Havana’s port from waste accumulation, causing diseases that spread throughout the population.[4]

In Holguín, the shortage of doctors to care for the affected population was another main challenge in fighting the epidemics. In July, 1853 local authorities asked the Board of Health to transfer Dr Manuel Castellanos to a rural area to care for cholera patients. Despite the absence of doctors offering services to this area, the Board denied the request arguing there were too few doctors in Holguín for the urban population. The city had been divided into five zones, with one doctor taking the lead and another physician in charge in each of the other four zones, plus one in the Military Hospital, another in the Charity Hospital and two in the Board of Health. This made a total of nine doctors, not enough to address the epidemic. The Board also argued that if Dr Castellanos attended to this rural population, he would have to leave another doctor in charge of his work.[34] This shows how difficult it must have been for doctors to care for the sick in epidemic periods. The lack of medical services in other towns highlights an overall problem in the colony, albeit more serious in the eastern region.[4]

Board of Health members continued to conduct routine inspections of food and liquor points of sale. In 1857, these establishments were inspected and spoiled food and adulterated liquor were found. The Urban Health Police ordered that they be collected and burned.[34]

In April 1862, Holguín suffered a new smallpox outbreak which, like the others, disproportionately affected the poor. The public health sector had few resources to tackle the epidemic, as demonstrated by the terrible conditions patients faced at the Charity Hospital. The Administrator of this facility wrote to the Board of Health, that the hospital was incapable of caring for the infected (…) due to the risk of spreading the epidemic to other sick people. Thus it was decided (…) to rent a house with six beds (…) for the poor, indolent and outsiders with no family.[34]

Smallpox outbreaks continued unabated over the next several years. In January 1865, in response to numerous smallpox outbreaks in several communities since the beginning of the decade, the Cuban Superior Board of Health published a circular attributing the main causes of smallpox propagation to absence of early diagnosis and treatment, insufficient monitoring of reported cases and health authorities’ abandonment of vaccination efforts. The Board of Health decided to inform Holguín’s Governor of the circular’s contents, to promote joint efforts to prevent further spread of the disease.[36]

Holguín’s Board of Health during Cuba’s independence wars: 1868–1878 and 1895–1898 During the Ten Years’ War (1868–1878), the public health system operated under the Spanish military health system. Documentation on Boards’ of Health work is sparse for this period. However, smallpox, yellow fever, cholera and other diseases returned with force to population centers in Holguín and throughout the island, afflicting both the Cuban population and Spanish troops.[38]

Despite Boards’ of Health insistence on smallpox vaccination, this was not effectively accomplished in Holguín during the Ten Years’ War, since public health was all but completely neglected. There is only one document available from this period, dated 1875, regarding a meeting of the Board of Health which, practically bankrupt, was forced to address a new outbreak of this dreadful disease. Lacking the necessary resources, the Board requested help from all the city’s administrative, judicial and religious entities to support the vaccination campaign and promote prompt reporting of new cases. This call for help reveals the institution’s inability to address public health problems and reflects the scant level of support by colonial governing authorities. [39]

Yellow fever, one of the main pandemics of the 19th century, did not severely affect the population of Holguín until the beginning of the independence war of 1868. Board of Health minutes make no mention of yellow fever in the city during this period. However, Toledo, in his study of yellow fever in Cuba, records its occurrence there in 1857, although without data on the number of people infected.[40]

Once the first war was over in 1878, the colonial government approved a new territorial division into six provinces: Pinar del Río, Havana, Matanzas, Santa Clara, Puerto Principe and Santiago de Cuba. The new divisions led to a reorganization of the health sector that appears in the plans of March 12, 1879 approved by the Governor General of Cuba, establishing Provincial and Municipal Health Boards, which would report to the then named Superior Health Board. The Provincial Boards corresponded to each of the six new provinces, while the Municipal Boards were divided into coastal and territorial. The plan confirmed the new Governor General of Cuba and the new Civilian Governors and Mayors as higher directors of civilian health in their respective administrative demarcations, leaving the Boards as mere advisory bodies. [28]

From 1878 to 1895, Cuba made great strides in the field of health: in 1881, Dr Carlos J. Finlay presented his discovery of the vector transmitting yellow fever and his recommendations of measures for the disease’s eradication; cholera was eliminated in 1882, and the administration of rabies vaccine began.[15] However, information on the work of the Holguín Board of Health is virtually nil for this period.

With the independence war of 1895, public health was put to the test throughout the country. The return of diseases such as cholera, smallpox and yellow fever severely taxed the national and provincial health systems. According to research on the mortality rate of Spanish troops in Holguín, 1073 soldiers died during the war, 550 due to yellow fever. In 1896, the forced relocation of entire rural populations into the cities under the governorship of Valeriano Weyler caused an increase in infectious diseases. The Boards of Health across Cuba, deprived of funds and authority and completely disorganized, were weak in the face of the many diseases that affected Spanish troops and the general population (dysentery, smallpox, malaria and typhoid fever).[38,41]

CONCLUSIONS

Cuba’s Boards of Health were created in the 19th century by the Spanish colonial authorities to organize measures for public health and hygiene, and to address the frequent epidemic outbreaks that plagued the island. To do so, they directed inspections of ports, asylums, hospitals, food markets and pharmacies. To carry out their responsibilities, they collaborated with other organizations such as the Royal Protomedicato Court, the Board of Vaccines, the Central Board of Charity and the Urban Health Police.

In Holguín during this period, the Board of Health took measures to prevent diseases such as cholera and smallpox. No records are available on its work to counteract another great pandemic of the century: yellow fever. The Board tackled health problems by mitigating damage. It was more active from 1850 to 1865. Its decline, beginning in the 1870s, was due to the colonial government’s inability to support the actions of such an important institution created to safeguard the population’s health and sanitary conditions.

References

- Varela Peris F. El papel de la Junta Suprema de Sanidad en la política sanitaria española del siglo XVIII. Acta Hisp Med Sci His Illus [Internet]. 1998 [cited 2019 Feb 9];18:315–40. Available from: https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/dynamis/02119536v18/02119536v18p315.pdf. Spanish.

- Portuondo F. Historia de Cuba hasta 1898. Havana: Editora del Consejo Nacional de Universidades; 1965. p. 257–301. Spanish.

- Delgado García G. Conferencias de Historia de la Administración de la Salud Pública en Cuba. Cuaderno de Historia de la Salud Pública. Nº81 [Internet]. Havana: ECIMED; 1996 [cited 2018 Nov 20]. Available from: http://bvs.sld.cu/revistas/his/vol_1_96/hissu196.htm. Spanish.

- Beldarrain Chaple Enrique. Las epidemias y su enfrentamiento en Cuba 1800–1860 [thesis] [Internet]. [Havana]: University of Medical Sciences of Havana; 2010 [cited 2018 Nov 20]. 128 p. Available from: http://tesis.sld.cu/index.php?P=FullRecord&ID=387&ReturnText=Search+Results&ReturnTo=index.php%3FP%3DAdvancedSearch%26Q%3DY%26FK%3DBeldarrain%2BChaple%2BEnrique%26RP%3D5%26SR%3D5%26SF%3D62%26SD%3D1. Spanish.

- Toledo Curbelo GJ. El pensamiento preventivista en José Martí. Rev Cubana Hig Epidemiol [Inter net]. 2005 [cited 2018 Nov 8];43(1). Available from: http://scieloprueba.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1561-0032005000100008&lng=es&nrm=iso. Spanish.

- Sánchez Valdés L. Proceso y resultados de la prevención comunitaria del dengue en Cuba [thesis] [Internet]. Havana: Pedro Kourí Institute of Tropical Medicina; 2006 [cited 2019 Feb 10]. 159 p. Available from: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-34022013000100008. Spanish.

- Batlle Almodóvar M, Dickinson F. Notas para una historia del cólera en Cuba durante los siglos XIX, XX y XXI. Rev Anales Acad Cienc Cuba [Internet]. 2014 Jan 29 [cited 2019 Feb 9];4(1). Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=2ahUKEwigjbS7-cfgAhUo1VkKHVSHATsQFjADegQIBRAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.revistaccuba.cu%2Findex.php%2Frevacc%2Farticle%2Fdownload%2F103%2F103&usg=AOvVaw2ILtwbeiEzTjVWlLg3GVIv. Spanish.

- García Castañeda J. La Municipalidad Holguínera 1800-1850. Holguín: Ediciones Holguín; 2002. p. 1–43. Spanish.

- Campos Suárez A. Dimensión social de las enfermedades. Estudio en el Holguín colonial de 1800 a 1878 [thesis]. [Holguín]: Universidad de Holguín. Facultad de Humanidades. Departamento de Historia; 2011. Spanish.

- Jori G. Población, política sanitaria e higiene pública en la España del siglo XVIII. Rev Geog Norte Gr [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2018 Jun 18];54:129–53. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34022013000100008. Spanish.

- Aguilá Solana I. Consideraciones sobre la medicina en la España del siglo XVIII según algunos viajeros franceses [Internet]. Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza; 2007 [cited 2019 Feb 9]. p. 31–47. Available from: https://www.google.com.cu/search?source=hp&ei=OfluXNqLGsresAW34rmQDA&q=Consideraciones+sobre+la+medicina+en+la+Espa%C3%B1a+del+siglo+XVIII+seg%C3%BAn+algunos+viajeros+franceses&btnK=Buscar+con+Google#. Spanish.

- Tejera Concepción JF. La salud pública en Cuba durante el periodo colonial español [Internet]. Málaga: Universidad de Málaga; 2008 [cited 2018 Jun 18]; [about 4 screns]. Available from: www.eumed.net/rev/cccss/02/jftc10.htm. Spanish.

- Astrain Gallart M. El Real Tribunal del Protomedicato y la profesión quirúrgica española en el siglo XVIII. Acta Hisp Med Sci Hist Illus [Internet]. 1996 [cited 2019 Feb 10];16:135–50. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=9&ved=2ahUKEwjqmeCr-8fgAhVPj1kKHRjQBjwQFjAIegQIBBAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fddd.uab.cat%2Fpub%2Fdynamis%2F02119536v16%2F02119536v16p135.pdf&usg=AOvVaw18n68qq0GokyOZGA7sTfie. Spanish.

- Medina-De la Garza Carlos E, Koschwitz Martina-Christine. Johann Peter Frank y la medicina social. Med Univ. 2011;13(52):163–8.

- Delgado García G. La salud pública en Cuba durante el período colonial español. Cuad Historia Salud Pública [Internet]. 1996 [cited 2018 Nov 15];81. Available from: http://bvs.sld.cu/revistas/his/vol_1_96/his09196.htm. Spanish.

- Mantovani R. O que foi a polícia médica? Hist Cienc Saude-Manguinhos [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0104-59702018000200007. Portugues.

- Martin Tardío JJ. Las epidemias del cólera del siglo XIX en Mocejón (Toledo) [Internet]. [place unknown]: [publisher unkown]; 2004 [cited 2018 Jun 21]. 184 p. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=http://www.bvsde.paho.org/texcom/colera/sigloxix.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjP866855PjAhVwk-AKHa8IDzsQFjABegQIAxAB&usg=AOvVaw2okyAaicodZl3HAzDCoWYU. Spanish.

- Vera Bolaño M, Pimienta Lastra R. La acción sanitaria pública en el Estado de México: 1824-1937. Polít Cultura [Internet]. 2001 Fall [cited 2018 Nov 13]. Available from: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/267/26701604.pdf. Spanish.

- Martí J. Obras Completas. Tomo 8. Havana: Editorial Nacional de Cuba; 1965. p. 298. Spanish.

- Rodas Chaves G. Visión histórica de la antinomia salud-enfermedad. Enfermedades en Quito y Guayaquil Siglos XIX y XX [Internet]. Quito: Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar; 2010 [cited 2018 Nov 13]. Available from: http://www.uasb.edu.ec/UserFiles/380/File/Vision%20historica%20de%20la%20antinomia%20salud-enfermedad.pdf. Spanish.

- Fernández Muñiz A. Breve Historia de España. Havana: Editorial Ciencias Sociales; 2008. p. 125–210. Spanish.

- Espinosa López JA. El bicentenario de la introduccion de la vacuna en Cuba. Rev Cubana Salud Pública [Internet]. 2004 Jun [cited 2019 Jun 20];30(2) Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34662004000200012&lng=esPérez Concepción H. Holguín desde sus inicios hasta 1898. Holguín: Ediciones Holguín; 1992. p. 5–25. Spanish.

- Pérez Concepción H. Holguín desde sus inicios hasta 1898. Holguín: Ediciones Holguín; 1992. p. 5–25. Spanish.

- Archivo Histórico Provincial de Holguín (AHP). Fondo Tenencia de Gobierno y Ayuntamiento (TGA). Legajo 65. Expediente 1949. Spanish.

- AHP. TGA. Legajo 64 I. Expediente 1943. Spanish.

- López Serrano E. Desarrollo histórico de las estadísticas sanitarias en Cuba. Cuad Hist Salud Pública [Internet]. 2002 Jan–Jun [cited 2018 Nov 15];91:206–18. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0045-91782002000100014&lng=es. Spanish.

- AHP. TGA. Legajo 64 (II), Expediente 1946. Spanish.

- Martínez-Antonio FJ. La Sanidad Española en Cuba antes y después de la Guerra de los Diez Años. Scripta Nova Rev Electrónica Geog Cienc Soc [Internet]. 2012 Nov 1 [cited 2018 Nov 15];XVI(418):20. Available from: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-418/sn-418-20.htm. Spanish.

- González Ochoa Y. Análisis histórico-contable de la Real Hacienda en Cuba colonial: la Caja Real de la Villa de Santa Clara (1689-1831) [thesis]. [Havana]: Editorial Universitaria; 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 9]. 197 p. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjt7IWpgcjgAhWqtlkKHU9tCDkQFjAAegQIChAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fbeduniv.reduniv.edu.cu%2Ffetch.php%3Fdata%3D1668%26type%3Dpdf%26id%3D1673%26db%3D1&usg=AOvVaw3oziblRbG6hmkP0qE0cvXy

- Doimeadios Cuenca E, Hernández M. Apuntes para una historia del municipio Gibara (1492-1878). Holguín: Ediciones Holguín; 2008. p. 46–8. Spanish.

- AHP. TGA. Legajo 139. Expediente 5273. Spanish.

- AHP. TGA. Legajo 139. Expediente 5281.

- Campos Suárez A. La Junta Municipal de Beneficencia de Holguín. Su creación y desenvolvimiento hasta 1878. Rev Caribeña Cienc Soc [Internet]. 2013 Nov [cited 2019 Feb 9]; [about 3 screens]. Available from: http://caribeña.eumed.net/beneficencia-Holguín/. Spanish.

- AHP. Fondo TGA, Legajo 139, Expediente 5279.Spanish.

- Ramírez AL. El cólera morbus en Guatemala: Las Juntas de Sanidad y prácticas médicas en la ciudad, 1837. Estudios Digital [Internet]. 2017 Aug 21 [cited 2018 Nov 11];8. Available from: http://iihaa.usac.edu.gt/revistaestudios/index.php/ed/article/view/216

- AHP. Fondo TGA. Legajo 139, Expediente 5277. Spanish.

- AHP. Fondo TGA. Legajo 139, Expediente 5275. Spanish.

- Delgado García Gregorio. Desarrollo Histórico de la Salud Pública en Cuba. Rev Cubana Salud Pública [Internet]. 1998 Jul–Dec [cited 2018 Nov 15];24(2)110–8. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34661998000200007. Spanish.

- AHP. Fondo TGA. Legajo 139, Expediente 5276. Spanish.

- Toledo Curbelo GJ. La otra historia de la fiebre amarilla en Cuba. 1492-1909. Rev Cubana Hig Epidemiol [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2018 Nov 20];38(3):220–7. Available from: http://bvs.sld.cu/revistas/hie/vol38_3_00/hie11300.htm. Spanish.

- Izquierdo Canosa R. Viaje sin regreso. Havana: Ediciones Verde Olivo. 2001. p. 32. Spanish.

THE AUTHORS

Adiuska Calzadilla-González (Corresponding author: acalzadillag@uho.edu.cu), historian with a master’s degree in Cuban history and culture. Assistant professor, Gibara Municipal University Center, Holguín, Cuba.

Isabel María Calzadilla-Anido, historian with a master’s degree in Cuban history and culture. Associate professor, Gibara Municipal University Center, Holguín, Cuba.

Aliuska Calzadilla-González, dentist with a master’s degree in emergency dentistry and specializations in comprehensive general dentistry and maxilofacial surgery. Assistant professor and adjunct researcher, Surgery Department, Gustavo Aldereguía Lima General Teaching Hospital, Gibara, Holguín, Cuba.