INTRODUCTION

Since 1978, WHO has emphasized the importance of primary health care (PHC) for promoting and protecting population health.[1] PHC is highlighted as the mechanism through which countries can provide better health to persons, families and communities, with greater equity and lower costs,[1,2] because it “brings promotion and prevention, cure and care together in a safe, effective and socially-productive way at the interface between the population and the health system.”[2]

Colombia is a culturally and ethnically diverse country with a highly varied demographic and epidemiologic profile, and an increased burden of chronic non-communicable diseases in the past decade without yet having eradicated infectious diseases.[3–5] Until recently, Colombia’s health system favored development of a hospital-based, curative health care model, oriented toward highly specialized care (the system revolving around specialists) under a free-market model (with users seen as consumers and with a variety of public and private insurers and service providers) that generates inequities in financing and limits access to health care, patient-centered care and community-based health improvements.[6]

In 2011, Law 1438 modified Colombia’s health system, putting PHC legally at the center of the system to address the country’s health priorities, emphasizing:

- public health actions such as health promotion and disease prevention;

- coordination of intersectoral actions;

- a culture of self-care;

- comprehensive health care involving individuals, families and communities; and

- active community participation and local approaches to attaining long-term, continuous and intercultural attributes of care.[7–9]

This article describes an intervention based on PHC and community-oriented primary care (COPC) principles,[10] aimed at building capacity for community participation to change population health status in Colombian communities.

INTERVENTION

Purpose, rationale and participants The Citizenship for Healthy Environments (CxES), a qualitative participatory action research (PAR) project to build community capacity to influence health, was carried out from January 2012 through June 2014 (30 months) with organizations in Bogotá and Cundinamarca, Colombia. In alliance with several institutions (Corona Foundation, Universidad de La Sabana, Organization for Excellence in Health, Community Development Consortium and Social Foundation) the authors invited several community organizations to become part of a joint project.

The rationale for CxES was that implementation of PHC initiatives aimed at solving priority health needs requires the integration of multiple actors (decision makers, health institutions, academia, human resources in health, and communities),[11,12] with the community playing a major role in successfully leading and managing this type of initiative and adapting it to local conditions.[13,14] COPC is an approach that places the community at the center of PHC; it enables concerted, community-based identification of the population’s problems and needs and their solutions, transforming health services and improving local capacity to bring about behavioral changes in the population.[15–17] In Colombia, however, the population and local health department and hospital officials are barely aware of PHC and COPC concepts or the practical application of PHC-based initiatives.[13,18]

PAR was selected because it is a methodology oriented toward generating change in persons using collective experience as a starting point (beginning with an assessment of community needs and problems) through an intersectoral approach and planning and implementation of actions for health improvement. Both quantitative and qualitative methods can be used for PAR, which serves as the foundation of COPC because it contributes to community contextualization, health assessment, prioritization, program implementation, and ongoing evaluation and improvement.[16,19]

PAR is carried out in complex sociopolitical contexts where dialogue and negotiation about objectives and means are integral to researchers building relationships with participating communities. In building such relationships, PAR encourages deepening local knowledge and stimulates interest in becoming part of research to better understand the community’s health. PAR increases the community’s understanding of its health status and empowers local actors to take committed action.[20] Its results are not limited to description but rather focus on action to improve public health practice, complementing common epidemiologic approaches and promoting capacity to conduct research at the local level.[21,22]

Participating organizations Organizations were recruited that were involved in various community actions addressing diverse health problems and vulnerabilities (children, people with disabilities, pregnant women, older adults or victims of armed conflict in Colombia).[5] Organizations were selected based on the following criteria: organizational life (people in the organization work collectively toward a common goal and distribute responsibilities accordingly; development of actions oriented toward a specific goal and in a particular community); prioritization of collective over individual interests; and influence in the surrounding area the organization’s territorial location.[23] The eight participating organizations included public, private, religious or charitable, and community-based groups: two grassroots women’s organizations in Soacha (Families for Progress and the We Are Women, We are Families Association), one school in Sopó (Paul VI State School), four institutions providing services to vulnerable communities in Bogotá (Center for Stimulation and Development, Royal Friends Foundation, Child Welfare Association, and Medalla Milagrosa Ambulatory Care Center), and one institution with links to the rest (the Archdiocese Food Bank).

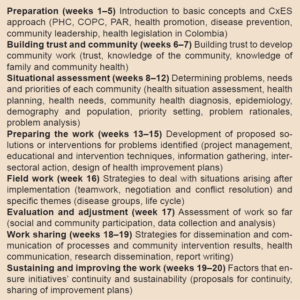

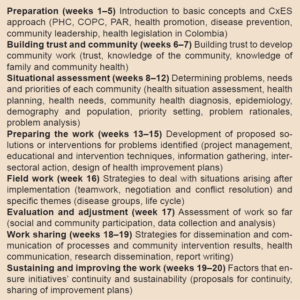

Activities Training community leaders for health initiative management Leadership trainers were eight professors from Universidad de La Sabana (three physicians and two nurses, all community health professors with master’s degrees and at least eight years’ experience in their respective professions) and the Community Development Consortium (a psychologist, a lawyer and a social worker, all with experience in social development in grassroots community organizations). Thirty leaders enrolled in the training, three or four selected by each organization based on the following criteria: current membership, responsibility for developing actions related to health or its determinants, length of time in the organization, interest, and time commitment. Training was based primarily on COPC principles[15] and Universidad de La Sabana’s community health experience. A modular, cyclical training process was designed to give leaders an opportunity to reflect on their understanding of PHC and COPC concepts, and to identify problems and needs in their communities.[10,17,24−26] The training lasted a total of 20 weeks over six months in weekly five-hour sessions using a variety of pedagogical techniques including master classes, practical demonstrations, debates, case studies and problem-based learning, supported by an online learning platform for complementary asynchronous reflection and discussion outside meetings.

Development and implementation of organizational improvement plans As part of the training, each organization developed and submitted a proposal for an improvement plan to address one priority problem. Once each proposal was formulated, it was implemented based on the principles covered in the training (16 months) (Table 1). Four tutors or facilitators supervised and participated (known as accompaniment) in practical implementation of the plans until the end of the project. Tutors were professors of community health at Universidad de La Sabana (three public health physicians and one public health nurse, all with master’s degrees), who were selected for having at least five years’ experience in community health actions.

Systematization of experiences and extraction of lessons learned Systematization was carried out simultaneously with the other two activities and throughout the process (a progress and adjustment report reflecting achievements and challenges midway through the process, and a final report on achievements, challenges and commitments). Content analysis was carried out on all reports, as well as photographic records, meeting notes, field journals and recordings of each plan’s activities. This activity involved analytical reflection and reconstruction, leading to knowledge generation from and for practice, through extraction and comprehension of lessons learned.[27,28]

An external team from the Community Development Consortium (an economist and a psychologist with experience in social development and qualitative research who were not part of the training and planning team) conducted systematization. They held semistructured interviews, triangulated data from all sources, obtained lessons learned from the pedagogical process, and reviewed and performed content analysis on documents generated by the organizations (community description and needs assessment, improvement plan, progress and adjustment reports, partial results, and final reports). The four tutors and one representative of each organization were interviewed based on an open-ended question: What factors enable or limit citizen capacity-building, generating a sense of ownership in the community and the territory for building a healthy environment? Three analytical categories were defined: (1) citizen capacity-building for PHC (individual and collective competencies to be developed in grassroots PHC community managers); (2) intra- and interinstitutional conditions organizational and community factors needed for creation of healthy environments; and (3) sense of ownership elements that foster behaviors contributing to healthy environments.

Table 1: Training modules, content and topics

COPC: community-oriented primary care CxES: Citizenship for Healthy Environments PAR: participatory action research PHC: primary health care

Data were organized and validated by two people from the systematization team, two tutors and two members of participating organizations, who identified lessons learned in each category. This activity was ongoing throughout the process but most intensively in the six months following implementation.

Ethics All organizations gave written informed consent to participate, by means of a voluntary agreement setting out their understanding that the project originated in the community, whose participants and organizations were the owners and active subjects of the process.[29]

RESULTS AND LESSONS LEARNED

Training of community leaders Of the 30 leaders who initiated training, 28 completed it (93.3%). Training objectives were met, including comprehension and explanation of their reality based on assessments of their communities’ principal needs and problems (Table 2). The training phase included their designing improvement plans and leaders expressly committing to lead their organizations in implementing them.

Organizational improvement plans Once each organization had defined their problems and needs, they designed an improvement plan related to one problem, defined by type of social response, vulnerability addressed and organizational characteristics. In all eight improvement plans, interventions were based on promoting healthy lifestyles, improving living conditions and finding opportunities for participation. The main results were evaluated per objectives, achievements and indicators set forth in the planning stage, using quantitative and qualitative instruments according to each organization and topic (Table 3).

Table 2: Community leader training results

PHC: primary health care

Systematization In the citizen capacity-building for PHC category, organized actions regarding PHC were understood in direct relation to participants’ empowerment as central actors in health promotion, disease prevention and a culture of self-care. The aforementioned empowerment results were facilitated by having taken on a community health initiative based on organizations’ protagonism in identifying their own PHC needs and strategies for action, by breaking with the dynamic usually found in non–community-oriented interventions. Changes were observed in perception of health as a collective matter, in which the subjects are protagonists in generating healthy community environments, helping overcome a hospital-centric vision. Throughout the training process and during plan implementation, it was observed that, as part of the PAR process, organizations made a clear conceptual and practical differentiation between disease prevention and health promotion, the latter understood as a collective matter and not the exclusive purview of the health system.

In the intra- and interinstitutional conditions category, it was emphasized that sustainability of building healthy environments with community participation requires a regional approach and not only training of people and organizations to act as replicators in their surroundings. This was because improvement plans were limited by organizational characteristics and did not involve all sectors in their context, health institutions among them. Given the heterogeneity of organizational contexts, these were expected to have only modest influence in their territory. At the same time, such heterogeneity was useful for comparing different experiences to generate lessons learned for creation of a PHC model with community participation.

Intersectoral work in PHC may be oriented toward influencing policies as well as broadening and improving the quality of interest groups’ action strategies. Throughout the training and accompaniment process, participants displayed an interest in connecting with other actors they had not initially considered influential for achieving healthy life styles; this interest enabled leaders to facilitate opening new spaces for participation by other community members. Initiatives for creating alliances and seeking opportunities for greater influence in their surroundings varied by type of organization, organizational structure, flexibility for change and ownership of PHC’s conceptual framework (Table 3).

In the sense of ownership category, community leaders expressed and reflected in the improvement plans that family and nutrition are two central elements in community ownership of healthy lifestyles and environments. Nutrition was not given special emphasis during the training process or in drafting improvement plans, but organizations made it a central focus of their initiatives. This may suggest that nutrition is a fundamental first step in developing community ownership of healthy lifestyles. Organizations certainly considered nutrition a main driver and promoter of healthy behavior within families.

Table 3: Community improvement plans by issue, reach and main results

ARD: acute respiratory disease PHC: primary health care

One of the main factors influencing the sense of ownership of healthy lifestyles and environments is related to organizations’ communication mechanisms and strategies. The experience demonstrated the effects of organizations’ participation in local discussion forums and community radio to present ideas, challenges and strategies promoting the concept of health as a social construct requiring broad participation.

General lessons This project demonstrates the potential importance of community participation in developing health programs and confirms the utility of working with preexisting social capital to foster community empowerment.[30,31] PAR methodology favored development of PHC action in organizations, guaranteeing the initiatives’ continuity and adjustment to the COPC conceptual framework,[10,17,19] as well as enabling community members to claim ownership of the research. The intervention showed that developing community-based health initiatives is possible and can generate greater sustainability and sense of ownership.

Experiences in Colombia have traditionally focused primarily on top-down or institutional PHC initiatives rather than on integrating the community at the grassroots level.[13,18] It is therefore important to involve all the actors in order to strengthen PHC initiatives and meet the population’s health needs.[11,15] A community participation approach to building healthy environments requires overcoming an excessive focus on health care services, which can encourage people to depend on treating specific ailments rather than addressing their fundamental vulnerabilities and improving their health (bearing in mind the importance of including the hospital sector to achieve more comprehensive plans). Linking organizations with PHC training and action processes does not in itself guarantee that the process will include all social actors present in a community, nor that it will bring about tangible changes in health status, but needs to be matched with changes to social determinants and generation of community leadership and empowerment.

CxES contributes important lessons for implementing Colombia’s new, legislatively mandated,[7] comprehensive health care model,[32] which includes prevention, promotion, diagnosis, treatment and palliative care, all under a local approach in which the community plays a key role. It facilitated and evaluated development of primary care initiatives in different types of organizations to address a variety of problems. In all cases, participants demonstrated comprehension of their role as health agents, promoting community participation and intersectoral action. Forming alliances among community actors, health services and academic institutions that train human resources is equally important for achieving knowledge transfer to all necessary social actors, thus ensuring sustainability of PHC-based health systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank participating communities and their leaders and organizations, as well as the tutors and facilitators who accompanied the CxES process.