ABSTRACT

A major challenge to achieve health coverage in Nigeria is expansion of health access to the poor, vulnerable and informal sectors, which constitute over 70% of the population of more than 186 million. Evidence from other countries suggests that it is difficult for contributory insurance schemes to achieve universal health coverage in such conditions, especially with such a large informal sector. In fact, Nigeria’s national social health insurance program has provided coverage to less than 5% of the population since its implementation in 2005, private voluntary health insurance has shown poor potential to extend coverage, and community-based health insurance has failed to expand access to poor, vulnerable and informal sector populations as well. Decentralization of health insurance to the states has limited potential to expand health insurance coverage for the poor, vulnerable and those in the informal sector. Furthermore, social health insurance in many developed countries has taken many years to achieve universal health coverage.

This paper suggests that policy makers should consider adopting a tax-based, noncontributory, universal health-financing system as the primary funding mechanism to accelerate progress toward universal health coverage. Social health insurance and its decentralization to states for formal sector workers should serve as a supplement, while private voluntary health insurance should cover better-off groups. Simultaneously, it is critical to tackle issues of poor governance structures, mismanagement of funds, corruption, and lack of transparency and accountability within regulatory and implementing agencies, to ensure that monies allocated for expanded health insurance coverage are well managed.

Although the proposed universal health coverage reform may take some years to achieve, it is more feasible to collect taxes, improve tax administration and expand the tax base than to enforce payment of contributions from nonsalaried workers and those who cannot afford to pay for health insurance or for services out of pocket.

KEYWORDS Health financing, access to health care, health services accessibility, tax-based universal system, financial risk sharing, Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

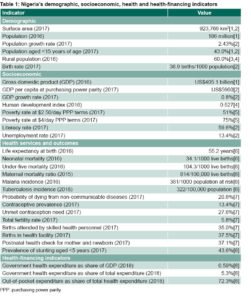

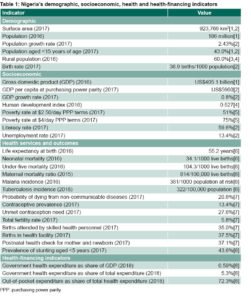

Nigeria—Demographic, administrative, socioeconomic and health context Nigeria has the largest population of any African country, an estimated 186 million in 2016.[1] It is rich in natural resources, particularly oil. Bordered by Benin to the west, Chad and Cameroon to the east and Niger to the north, Nigeria is a political federation with 36 states and a federal capital territory (in six geopolitical zones), and multiple ethnic groups. It is classified among the low- and middle-income countries; Table 1 displays selected demographic, socioeconomic, health and health-financing indicators.[1−8]

As can be observed, Nigeria’s performance in health indicators is poor and has not improved as fast as might be expected, given its per capita GDP greater than $2000.[1,2,8,9] In 2016, the first ten causes of death were malaria, HIV/AIDS, diarrheal diseases; lower respiratory tract infections, neonatal encephalopathy, ischemic heart disease, preterm birth, congenital defects, meningitis and neonatal sepsis.[10] In addition, there are variations in health status and health outcomes between rural and urban areas and across geopolitical zones and socioeconomic groups, as well as inequities in access to health care services. Informal employment constitutes over 90% of total employment in Nigeria.[11] Furthermore, 53.5% of Nigerians live in poverty ($1.90 a day) with 70% of the poor residing in rural areas.[12] The majority of Nigerians who remain uninsured are poor, unemployed and nonsalaried workers.

IMPORTANCE The article highlights the need for governments in Nigeria to adopt a tax-based, noncontributory, universal health-financing system in order to significantly extend health coverage and access, given the country’s large poor, vulnerable and informal sector population.

Nigeria’s health system is structured in primary, secondary and tertiary levels,[13] with the three tiers of government (national, provincial and local) sharing responsibility for provision of health services. The private sector delivers approximately 60% of health care services and the public health sector 40%.[14] Nigerians should have reasonable geographic access to health care with about 32,000 public and private primary health care (PHC) facilities spread across the country.[15] Nonetheless, new PHC facilities are needed in rural areas and the Northern states, especially those affected by conflict, in order to address geographical barriers to access.

The fact that Nigeria has consistently had the largest economy in Africa provides fiscal space for financing to meet the health needs of the population, including all Nigerians, but there has been limited progress in addressing health-financing challenges to date.[9]

Universal health coverage (UHC) and Nigeria UHC aims to increase equity in access to quality health care services and reduce associated financial risk.[16] Evidence from other countries suggests that it is difficult to implement contributory insurance schemes for UHC where there is a large informal sector.[17−19] According to WHO, expanding health insurance coverage to the entire population requires substantial funding from general tax revenues, these fully or partially subsidizing care for poor and vulnerable groups.[20] Countries like Thailand, Brazil and Costa Rica were able to achieve UHC by adopting tax-financed, noncontributory, universal coverage schemes to benefit particularly poor, vulnerable and informal sector (PVIS)populations.[21] General tax revenues have also been used to cover PVIS populations in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Vietnam, with tax financing predominant.[22]

Documentation from the 2014 Presidential Summit on UHC held in Nigeria,[23] the 2018 Health Policy Dialogue on UHC,[24] and the launch of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund under the National Health Act of 2014,[25] indicates that successive Nigerian governments have supported the objectives of UHC. Yet, health coverage is far from universal.

Nigeria’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) and UHC After several attempts to introduce health insurance beginning in the 1960s, legislation establishing the NHIS was passed in 1999 and the program launched in 2005 (after delays due to political instability).[26] NHIS is a contributory health insurance scheme (combining compulsory and voluntary contributions) targeted at formal sector workers as well as PVIS populations. It aims to ensure access to quality health care services, provide financial risk protection, reduce rising health care costs and ensure health care efficiency. NHIS has been implemented through programs such as the Formal Sector Social Health Insurance Programme, Mobile Health, Voluntary Contributors Social Health Insurance Programme, Tertiary Institution Social Health Insurance Programme, Community Based Social Health Insurance Programme, Public Primary Pupils Social Health Insurance Programme and Vulnerable Group Social Health Insurance Programme, which aim to provide health care services for children under 5 years, pregnant women, prison inmates, disabled persons, retirees and older adults.[27] However, NHIS has been performing poorly with very low coverage; since its implementation in 2005, evidence suggests that NHIS has provided health insurance coverage to less than 5% of the population.[21]

The Social Health Insurance Programme has entrenched inequities in access to health care as only federal government workers and their dependents are provided with coverage.[28] Community-based health insurance has also failed to expand coverage to PVIS populations,[29] and private voluntary health insurance has shown poor potential to extend health insurance coverage.[30] Voluntary membership, limited government support and poor management are some of the reasons why private voluntary and community-based health insurance do not work in Nigeria and result in high dropout rates, high administrative costs and low coverage of the poor.

Exemption schemes and waivers aimed at the poor and vulnerable groups have not been effective in increasing enrollment and addressing barriers to access for these groups due to problems associated with targeting and failure to enforce exemption systems. Thus, PVIS populations are disproportionately exposed to catastrophic and impoverishing effects of high out-of-pocket expenditures. Furthermore, the NHIS has been bedeviled with poor governance structures, mismanagement of funds, corruption, and lack of transparency and accountability.[31] Nigeria has to provide health insurance coverage for the >90% of its population who remain uninsured in order to achieve UHC by 2030.

A tax-financed noncontributory scheme has emerged as a viable option for financing UHC in countries at all income levels,

including those with large informal sector populations.[17,32−35] In addition, providing health insurance to PVIS populations represents a bottom-up approach to expanding coverage that is a feasible option for developing countries, including Nigeria.[22] Policy makers should consider a tax-based noncontributory universal health-financing system as the primary financing mechanism toward achieving UHC, as it is capable of addressing the factors responsible for poor enrollment in NHIS by PVIS populations.

Against this backdrop, this paper’s objective is to propose the design and effective implementation of a noncontributory mechanism for health financing toward achieving UHC in Nigeria. This UHC reform proposal is in the spirit of those used in Thailand, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, Philippines, Brazil, Argentina and Mexico, aiming to expand health insurance coverage to PVIS populations.[22,32]

DESIGNING A UHC STRATEGY (UHCS)

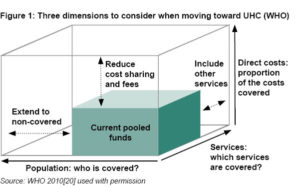

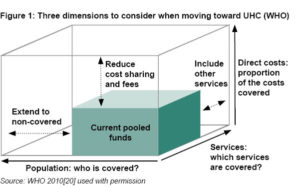

Figure 1 illustrates the dimensions of UHC: depth (proportion of costs covered), scope (range of services covered), and breadth (proportion of the population covered).[20]

A comprehensive health benefit package should be designed for the whole population (including PVIS populations) in order to ensure equity and access to essential health services. This package should include a portfolio of health services, complemented by a negative list of services, products and interventions that would not be tax funded under any circumstances—for example, medications not considered cost effective by health technology assessment agencies.[36,37] The following health services should be made available under the UHCS for the whole population (including PVIS populations): maternity services, emergency services, hospital services, physician services, pharmaceuticals, public health services, outpatient primary care, inpatient specialist care, preventive care, curative care, mental health care services, health promotion services, palliative care services and interventions for diseases.[22] This should be modelled on experiences in countries such as Chile and Colombia,[38] Liberia pre-Ebola[39] and Thailand.[40]

The package should also be guided by equity, financial protection and empirical evidence on cost-effectiveness of health services and interventions.[18,36,37] It should be constantly reviewed and refined as new evidence, technologies and preferences emerge.

[36,37] Beneficiaries of a noncontributory UHCS would not be allowed to seek medical care at secondary and tertiary care levels except with a referral from PHC facilities or in emergency situations. Efforts should be made to make the gatekeeper policy effective by ensuring improved quality in PHC and smooth running of referral processes.[30] The bulk of additional public health spending should be allocated to pay for PHC services because these services are currently woefully inadequate in Nigeria, and are globally recognized as the foundation of good health care.

With respect to provider payment mechanisms, capitation and diagnosis-related group mechanisms should be attached to prioritized and nonprioritized health care services under the UHCS rather than fee for service and copayments, which undermine the objectives of UHC.[41]

Tax base and revenue collection In Nigeria, governments at national and subnational levels need to increase the tax base to finance such a comprehensive health benefit package, a noncontributory UHCS, in order to expand coverage to all. This will provide the large funding pool needed for provision of health services for PVIS populations, the majority of the Nigerian population. Efforts to expand taxation should include taxes on tobacco, alcohol and sugary soft drinks, without increasing relative tax burden on PVIS populations who pay proportionately more of their income in taxes than their wealthier compatriots. Other tax sources that should be explored include effective collection of corporate and business taxes, especially of natural resources profits—including oil. Taxing oil profits properly would bring in significantly more funds without adversely impacting the poor.

Funds for the UHCS should be collected by government tax agencies from all potential sources of taxes: in addition to those mentioned above, these might include mobile phone use, luxury goods (such as cars, yachts and private jets), unhealthy foods, tourism and imported goods (such as salt, plastics, cereals, machinery, frozen fish, vehicles, iron and steel). Other sources of funding should include special levies on large and profitable companies, currency exchanges, financial transaction flows, diaspora bonds and luxury air travel.

In general, it is important to ensure that a progressive taxation model is adopted for such prepaid health financing, in which richer population groups pay a higher percentage of their income than poorer groups. The UHCS should be financed through allocation of these tax funds and innovative financing mechanisms by government tax agencies. Expected revenue from the various types of “sin taxes” proposed and the financial implications of the UHCS would be calculated by a technical working group composed of technical experts and stakeholders—such as legislators, academics, policy makers and civil society groups.

Pooling UHCS funds should create a pool that guarantees coverage of PVIS population health care costs. In other words, under the UHCS, risk associated with illness would be shared, rather than borne individually. Needs-based resource allocation mechanisms should be used rather than historical budgeting. It is recommended that the NHIS, together with the state social health insurance schemes (SSHIS) should simply manage, coordinate and regulate the UHCS, social health insurance, and voluntary health insurance. In addition, a different national purchasing agency and fund manager—preferably the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) at the national level and subnationally, the State Primary Health Care Development Agencies (SPHCDA)—should manage this pool of funds in order to ensure inclusivity and facilitate resource allocation and redistribution.[42,43]

Nigeria has a decentralized health system; hence, funding for a UHCS should come from the national and subnational levels of government. Federal and state governments should work together to enroll PVIS populations in the UHCS. The Boards of the NPHCDA and SPHCDAs as the new purchasing agencies and fund managers should allocate annual per capita budget directly to public and private PHC providers in the states based on registered population, weighted by health needs.

Strategic purchasing Tax funds generated for the UHCS should be allocated to purchase health services from public and private PHC providers, guaranteeing a comprehensive health benefit package for PVIS populations, a responsibility assigned to both the NPHCDA and SPHCDAs as administrators/managers of the UHCS. These agencies should also coordinate registration and accreditation of public and private PHC facilities for participation in the UHCS scheme and negotiate prices for health services included in the comprehensive health benefit package. A contract should be drawn up between the new national purchasing agency and PHC providers, specifying the health benefit package, cost of health services, payment mechanisms and other performance requirements related to provision of health services for PVIS populations.[32] The proposed mode of payment such as capitation and diagnosis-related group rates should be fair and updated annually, as is done in Thailand,[20] in contrast to Nigeria’s situation with failure to update capitation rates for years.[28]

The NPHCDA and SPHCDAs should guarantee monitoring and supervision of health services provided by enlisted public and private PHC facilities, to ensure quality of care and take necessary actions against poor practices. They should also ensure continuous availability of medicines, diagnostic equipment and constant improvements in health service quality. Programs should be developed to strengthen NPHCDA and SPHCDA purchasing skills, operational capacities and administrative capabilities.

BENEFITS OF A UHC STRATEGY

Affordability and financial accessibility The lack of direct out-of-pocket payment and user fees for public health care by PVIS populations would ensure financial accessibility for health services, thereby expanding coverage. Enlarging the tax base and achieving greater efficiency in managing health care resources would provide additional annual health spending needed to provide UHCS for PVIS populations. Public health spending of at least 3% of GDP is needed to kick-start this UHC reform, while governments work toward the goal of 5% of GDP in the long term. Government health expenditure as a percentage of total health expenditure would increase as a result of such a tax-based noncontributory universal health-financing system. Also, government health spending as a percentage of GDP would increase, since out-of-pocket payments for priority health services among poor and vulnerable groups would be virtually eliminated. However, the increase in government health spending as a percentage of total health expenditure and GDP would require significant political commitment and a serious attempt to increase the tax base and revenues, allocating a large share of these resources to health.

Equity and efficiency The UHCS would ensure equity in access to health care by allocating funds and purchasing health services based on health needs of PVIS populations. The design of a comprehensive health benefit package for the whole population, including PVIS groups, can be expected to ensure equity in health benefits in several ways. It would increase health services utilization among PVIS populations and prevent catastrophic health expenditures and resulting increased impoverishment. NPHCDA and SPHCDAs’ purchasing power would help control prices and increase access to quality care for beneficiaries. UHCS would generate greater funding with lower administrative costs.[32] It would shift funding away from tertiary care to PHC services for the PVIS population and ensure resource allocation to cost–effective interventions and services that address the heaviest burden of ill health among PVIS populations.[32] Thus, UHCS would ensure provision of resources to a range of health services at lower cost, while improving health outcomes and financial risk protection.[32]

Political acceptability, implementation and sustainability Political support for UHCS can be obtained based on the following principles and arguments:

- Access to health care is a right of all Nigerian citizens and should not depend on individual income or wealth.

- The current targeting of specific programmes for the poor is ineffective.

- There is low coverage with voluntary health insurance.

- PVIS populations cannot afford premiums/contributions.

- The current basic minimum package does not provide financial risk protection.

- Middle- and high-income households will support this proposal because of the benefits accruing from UHCS: increased utilization of and access to health services, reduction in out-of-pocket health payments, improved financial risk protection and improved health service quality.

Beneficiaries of a tax-based noncontributory health-financing scheme would ensure the reform’s continuity by demanding political and financial commitment from political parties during election campaigns. Effective and strong political leadership as well as succession planning within implementing and regulatory agencies—NHIS, SSHIS, NPHCDA and SPHCDAs—would enhance UHCS sustainability.

Payment mechanisms (capitation and diagnosis-related group rates) would be used along with a spending limit in order to enhance political acceptability of the UHCS by political actors at national and subnational levels. Development of operational capacity and administrative capability in purchasing organizations would promote effective UHCS implementation, also enhanced by effective communication and awareness among beneficiaries. The proposed UHCS is sustainable if governments can generate more tax revenue and effectively tackle corruption in the health sector by using an e-payment mechanism to block leakage of health care resources, as well as ensuring transparency and accountability. Funding UHCS through general tax revenue in the context of a strong tax collection mechanism would ensure its implementation over the long term.

As Nigeria has consistently had the largest economy in Africa, there is a potential for increasing the fiscal space for health financing to meet the health needs of the population and provide a comprehensive health benefit package. There is also fiscal space for increasing tax funding.

The creation of this health benefit package for PVIS populations would ensure increased utilization of and access to needed health care services without financial hardship. Poor service delivery for PVIS populations should be bridged by providing financial incentives for health workers in rural areas and increasing the number of health workers. Efforts should be made to address other factors affecting motivation and retention of health workers in rural areas such as low and unpaid salaries and incentives; housing difficulties and distance of housing from the workplace; travel costs and hardships incurred from commuting to health facilities as well as unmet career development priorities.[44]

DRAWBACKS OF CURRENT UHC REFORM EFFORTS

Social health insurance in many developed countries has taken many years to achieve UHC.[45] Although the proposed UHC reform for Nigeria may also take some years, it is easier to collect taxes, improve tax administration and expand the tax base than to enforce payment of contributions from nonsalaried workers and those who cannot afford to pay for health insurance premiums or out of pocket. Efforts to decentralize health insurance to the states have limited capacity to expand insurance coverage for PVIS populations, who constitute >70% of Nigerians.

The National Health Act (No. 8, 2014) established a Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) with 50% to be used to provide a basic minimum package of health services to all citizens in eligible primary and secondary health facilities.[46] However, this is not an adequate health-financing mechanism toward achieving UHC in Nigeria, because a limited health benefit package will not reduce high out-of-pocket payments that result in a high incidence of catastrophic medical expenditures and impoverishment for poor and vulnerable households.[47] Furthermore, donor funding fluctuates from year to year and is dwindling, while the Federal Government annual grant of ≤1% of its Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) to the BHCPF is at the mercy of political uncertainty. In fact, the 1% of the CRF to BHCPF has yet to be allocated or disbursed; the federal government promised to begin disbursement in August 2018.[48]

While uncertainties remain about inclusion of 1% of the CRF in the 2018 appropriations bill almost four years after the National Health Act became law, there was presidential approval, without legislative approval, of withdrawal of $469.3 million for purchase of aircraft from the US government.[49] This alone indicates a lack of political will or commitment to address the issue of inadequate health spending for Nigeria’s health system. Nor is it clear that state and local governments are committed to implementing the BHCPF, since their refusal to support similar policies over the decades has affected successful implementation.

In addition, the eventual approval of 57.15 billion naira (US$158.75 million) for BHCPF in the 2018 Appropriations Bill[50] may be affected by poor budget implementation and lack of clarity on how to manage the fund.

In any serious reform towards UHC, it will be critically important to tackle issues of inadequate governance, funding mismanagement, corruption, and lack of transparency and accountability within the NHIS, SSHIS, NPHCDA and SPHCDAs. This is essential to ensure that funds for expanding health insurance coverage to PVIS populations are well managed to provide equitable access to quality health care, financial risk protection and improved health outcomes. As indicated in this paper, there is urgent need for major tax policy reforms at national and subnational levels to increase general tax revenues from 6% of GDP to the international benchmark for developing countries of ≥15%,[51,52] and for these funds to be dedicated to provision of health insurance coverage, particularly for PVIS populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding health coverage to PVIS populations is a major challenge for achieving UHC in Nigeria. Evidence from other countries suggests that it is difficult to achieve UHC through contributory insurance schemes when there is a large informal sector. Therefore, policy makers should ensure design and effective implementation of a tax-based, noncontributory, universal health-financing system. This will be critical if Nigeria is to achieve UHC by 2030.

References

- The World Bank [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: World Bank; c2018. Where We Work. Nigeria at a glance; [updated 2017 Dec 12]; [cited 2018 Apr 25]. Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria

- Central Intelligence Agency [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency; c2018. Library. The world fact book: Nigeria; [cited 2018 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.html

- Welcome MO. The Nigerian health care system: need for integrating adequate medical intelligence and surveillance systems. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011 Oct;3(4):470–8.

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2016: Human Development for Everyone [Internet]. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2016 [cited 2018 Apr 25]. 271 p. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf

- The World Bank [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; c2018. Publications. Nigeria bi-annual economic update 2017: Fragile recovery; 2017 Apr [cited 2018 May 1]. 48 p. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/349511494584937819/Nigeria-Bi-annual-economic-update-2017-fragile-recovery

- World Health Organization. Reports. World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring health for the SDGs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 Jun 6. 85 p.

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2016−17, Survey Findings Report. Abuja (NG): National Bureau of Statistics; United Nations Children’s Fund; 2018 Feb. 525 p.

- World Health Organization. 2018. National Health Account: Nigeria [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 Feb 6 [cited 2018 Apr 25]. Available from: https://knoema.com/WHONHA2018Feb/national-health-accounts?country=1000340-nigeria

- World Health Organization. Nigeria: Factsheets of Health Statistics 2016 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 [cited 2018 Mar 30]. 7 p. Available from: http://www.aho.afro.who.int/profiles_information/images/3/3b/Nigeria-Statistical_Factsheet.pdf

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [Internet]. Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; c2018. Results. Country Profile. Global Burden of Disease Profile: Nigeria 2016; 2016 [cited 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.healthdata.org/nigeria

- International Labour Office. Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical picture. 3rd ed. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2018 Apr 30. 155 p.

- Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. Nigeria Country Briefing, Multidimensional Poverty Index Data Bank. Oxford: OPHDI, University of Oxford; 2017 [cited 2018 May 1]. Available from: http://www.dataforall.org/dashboard/ophi/index.php/mpi/country_briefings

- Asuzu MC. The necessity for a health system reform in Nigeria. J Community Med Primary Health Care. 2004 Jan;16(1):1−3.

- Federal Ministry of Health. National Strategic Health Development Plan (NSHDP) 2010−2015 [Internet]. Abuja (NG): Federal Ministry of Health; 2010 [cited 2018 Apr 25]. 134 p. Available from: http://www.health.gov.ng/doc/NSHDP.pdf

- Kress DH, Su Y, Wang H. Assessment of primary health care system performance in Nigeria: Using the primary health care performance indicator conceptual framework. Health Syst & Reform. 2016;2(4):302−18.

- Aregbeshola BS. Enhancing political will for universal health coverage in Nigeria. MEDICC Rev. 2017 Jan;19(1):42−6.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Patcharanarumol W, Ir P, Aljunid SM, Mukti AG, Akkhavong K, et al. Health-financing reforms in southeast Asia: challenges in achieving universal coverage. Lancet. 2011 Mar;377(9768):863−73.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Pitayarangsarit S, Patcharanarumol W, Prakongsai P, Sumalee H, Tosanguan J, et al. Promoting universal financial protection: how the Thai universal coverage scheme was designed to ensure equity. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013 Aug 6;11:25.

- Okungu V, Chuma J, Mulupi S, McIntyre D. Extending coverage to informal sector populations in Kenya: design preferences and implications for financing policy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Jan 9;18(1):13.

- World Health Organization. Health systems financing: path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 Nov 11. 106 p.

- McIntyre D, Ranson MK, Aulakh BK, Honda A. Promoting universal financial protection: evidence from seven low-and-middle-income countries on factors facilitating or hindering progress. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013 Sep 24;11:36.

- Cotlear D, Nagpal S, Smith O, Tandon A, Cortez R. Going Universal: How 24 Developing Countries are Implementing Universal Health Coverage Reforms from the Bottom-Up. Washington, D.C.: World Bank; 2015 Sep 28. 286 p.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; c2018. News. Presidential summit on universal health coverage ends in Nigeria; 2014 [cited 2018 Apr 25]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: http://www.afro.who.int/news/presidential-summit-universal-health-coverage-ends-nigeria

- Uwugiaren I, Ireogbu S, Oyedele D, Ajimotokan O, Ifijeh M, Obi P. At 2nd THISDAY Healthcare Policy Dialogue, Leaders Task Nigeria on Universal Coverage. Latest Nigerian News [Internet]. 2018 Apr 13 [cited 2018 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2018/04/13/at-2nd-thisday-healthcare-policy-dialogue-leaders-task-nigeria-on-universal-coverage/

- Essien G. Nigeria launches Basis Healthcare Provision Fund. Voice of Nigeria [Internet]. 2018 Apr 12 [cited 2018 Apr 25]; Health:[about 3 p.]. Available from: https://www.von.gov.ng/nigeria-launches-basis-healthcare-provision-fund/

- Uzochukwu B, Ughasoro MD, Etiaba E, Okwuosa C, Envuladu E, Onwujekwe OE. Health care financing in Nigeria: Implications for achieving universal health coverage. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015 Jul–Aug;18(4):437–44.

- National Health Insurance Scheme. National health insurance scheme decree No. 35 of 1999 [Internet]. Lagos: National Health Insurance Scheme; 1999 [cited 2018 Apr 25]. Available from: http://www.nigeria-law.org/National%20Health%20Insurance%20Scheme%20Decree.htm

- Onoka CA, Onwujekwe OE, Uzochukwu BS, Ezumah NN. Promoting universal financial protection: constraints and enabling factors in scaling-up coverage with social health insurance in Nigeria. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013 Jun 13;11:20.

- Odeyemi IA. Community-based health insurance programmes and the National Health Insurance Scheme of Nigeria: challenges to uptake and integration. Int J Equity Health. 2014 Feb 21;13:20.

- Onoka CA, Hanson K, Mills A. Growth of health maintenance organisations in Nigeria and the potential for a role in promoting universal coverage efforts. Soc Sci Med. 2016 Aug;162:11−20.

- Nwabughiogu L. Health insurance in tatters: N60 billion paltry 450,000 Nigerians! Vanguard [Internet]. 2017 Jul 9 [cited 2018 Apr 25]; News:[about 20 p.]. Available from: http://www.vanguardngr.com/2017/07/health-insurance-tatters-n60billion-spent-paltry-450000-nigerians

- McIntyre D. Learning from Experience: Health care financing in low and middle-income countries. Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research; 2007 Jan. 76 p.

- Mills A. Strategies to achieve universal coverage: are there lessons from middle income countries? [Internet] London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2007 Mar 30 [cited 2018 Apr 25]. 46 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/universal_coverage_2007_en.pdf

- Akazili J, Garshong B, Aikins M, Gyapong J, McIntyre D. Progressivity of health care financing and incidence of service benefits in Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2012 Mar;27 Suppl 1:i13–22.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Swasdiworn W, Jongudomsuk P, Srithamrongswat S, Patcharanarumol W, Prakongsai P, et al. Universal Coverage Scheme in Thailand: Equity Outcomes and Future Agendas to Meet Challenges. Background Paper, 43. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. 13 p.

- Glassman A, Giedion U, Sakuma Y, Smith PC. Defining a health benefits package: what are the necessary processes? Health Syst Reform. 2016 Jan 21;2(1):39−50.

- Glassman A, Giedion U, Smith PC. What’s in, what’s out? Designing benefits for universal health coverage. Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development; 2017. 357 p.

- Giedion U, Bitran R, Tristao I, editors. Health benefit plans in Latin America: a regional comparison. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank; 2014 May. 239 p.

- Hughes J, Glassman A, Gwenigale W. Working Paper 288. Innovative financing in early recovery: the Liberia health sector pool fund [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development; 2012 Feb [cited 2018 Apr 25]. 30 p. Available from: http://www.cgdev.org/files/1425944_file_Hughes_Glassman_Liberia_health_pool_FINAL.pdf

- Mohara A, Youngkong S, Velasco RP, Werayingyong P, Pachanee K, Prakongsai P, et al. Using health technology assessment for informing coverage decisions in Thailand. J Comp Eff Res. 2012 Mar;1(2):137–46.

- Lagarde M, Palmer N. The impact of user fees on health service utilization in low- and middle-income countries: how strong is the evidence? Bull World Health Organ. 2008 Nov;86(11):839–48.

- Van Oorschot W. Troublesome targeting: on the multilevel causes of non-take up. In: Ben-Arieh A, Gal J, editors. Into the promised land: Issues facing the welfare state. Connecticut: Praeger; 2001. p. 239–58.

- Spicker P. Targeting, residual welfare and related concepts: modes of operation in public policy. Public Adm. 2005 Jun;83(2):345–65.

- Ikpeazu AE. Can the Midwives Service Scheme (MSS) present an effective and health systems strengthening response to the shortages in hu man resources for maternal health services in Nigeria? [thesis]. [London]: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; 2018.

- Akazili J. Equity in health care financing in Ghana [PhD thesis]. [Cape Town (SA)]: University of Cape Town; 2010.

- National Assembly of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. National Health Act 2014 [Internet]. Lagos: National Assembly of the Federal Republic of Nigeria; 2014 [cited 2018 Apr 25]. 44 p. Available from: https://nass.gov.ng/document/download/7990

- Aregbeshola BS, Khan SM. Out-of-pocket payments, catastrophic health expenditure and poverty among households in Nigeria 2010. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018 Sep;7(9):798–806.

- Jannamike L. FG to commence disbursement of basic healthcare fund August – Osinbajo. Vanguard [Internet]. 2018 Jul 28 [cited 2018 Aug 7];News:[about 5 screens]. Available from: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2018/07/fg-to-commence-disbursement-of-basic-healthcare-fund-august-osinbajo/

- Busari K. Buhari ‘withdraws $462 million from excess crude account without national assembly approval’. Premium Times [Internet]. 2018 Apr 23 [cited 2018 Aug 7];News:[about 5 screens]. Available from: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/265969-buhari-withdraws-462-million-from-excess-crude-account-without-national-assembly-approval.html

- The Guardian News. Senate explains N57.15b vote for basic healthcare in 2018 budget. [Internet]. 2018 May 18 [cited 2018 Aug 7]; [about 4 screens]. Available from https://guardian.ng/news/senate-explains-n57-15b-vote-for-basic-healthcare-in-2018-budget/

- Aderinokun K, Chima O, Olaode F, Abone K, Alekhuogie N. Adeosun: Nigeria’s tax to GDP ratio among lowest in the world. [Internet]. 2017 Apr 23 [cited 2018 Sep 14] https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2017/04/23/adeosun-nigerias-tax-to-gdp-ratio-among-lowest-in-the-world/

- United Nations [Internet]. New York: United Nations; c2018. News. Countries urged to strengthen tax systems to promote inclusive economic growth; 2018 Feb 14 [cited 2018 Sep 14]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/financing/tax4dev.html

THE AUTHOR

Bolaji S. Aregbeshola (Corresponding author: bolajiaregbeshola74@gmail.com), public health specialist, Department of Community Health & Primary Care, College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Nigeria.

Submitted: May 09, 2018 Approved: October 07, 2018 Disclosures: None