Joan O’Connell MHSc PhD, Ana María Gálvez-González PhD, Jean Scandlyn PhD, María Rosa Sala-Adam MS DDS,

Xiomara Martín-Linares MS

ABSTRACT

In 2011, the US Department of the Treasury changed its regulations to allow US students to participate in short-term education programs in Cuba. Beginning in 2012, and each year thereafter, Cuba’s National School of Public Health and the Colorado School of Public Health have jointly taught a class on the Cuban public health system. The program goals are to provide US students with an opportunity to learn about the Cuban national health system’s focus on 1) prevention and primary health care services; 2) financial and geographic access to services and health equity; 3) continuum of care across the home, family doctor-and-nurse offices, polyclinics and hospitals; 4) data collection at all levels to understand health risks, including outbreaks, and to guide resource allocation; 5) assessing patients’ health and risks using a comprehensive definition of health; 6) multisectoral collaborations between the Ministry of Public Health and other Cuban agencies and organizations to address population health risks; 7) disaster preparedness, response and recovery; and 8) provision of international health assistance. The class incorporates information about health systems in Latin American and other Caribbean countries to provide context for understanding the Cuban health system.

The course includes: 1) seminars, online readings and discussions before travel to Cuba; 2) seminars at Cuba’s National School of Public Health, visits to Cuban national health institutions at all levels, from community-based family doctor-and-nurse offices and multispecialty clinics (polyclinics) to internationally recognized national health institutions, and guided visits and activities about Cuban culture and history during their 12 days in Cuba; and 3) followup course work upon return to the USA in which students integrate what they learned into their final class reports and presentations. During time spent planning, implementing and revising the program, both institutions have learned from each other about global health teaching methodologies and have laid a foundation for future teaching and research collaborations. To date, 49 individuals have participated in the program.

KEYWORDS Medical education, public health system, collaboration, Cuba, USA

INTRODUCTION

Cuba is known for implementing a public health model based on universal health coverage, equity and efficient resource allocation.[1–5] With a focus on prevention and primary care, Cuba has achieved health indicators that match or exceed those of countries with substantially more resources.[1–5] Many ask how Cuba has been able to accomplish this.

In 2011, the US Department of the Treasury changed its regulations on travel to Cuba to allow US students to participate in short-term education programs in that country.[6] Since 2012, Cuba’s National School of Public Health (ENSAP)[7] and Colorado School of Public Health (CSPH)[8] have jointly taught an annual class on public health in Cuba comparing it with approaches in other Latin American and Caribbean countries.

What can US students learn from studying the health system of a country where the government provides and finances health services and the average GDP is significantly lower than that of the USA? Furthermore, what are the benefits to Cuban and Colorado faculty who participate in the program? This paper addresses those questions and decribes ongoing collaboration between our two schools of public health.

IMPORTANCE Collaborative course development and teaching methods are key in this course, which provides opportunities for students and faculty members to learn about the way key health services and policies, curricula and teaching strategies are organized and implemented in Cuba.

COLLABORATION

Antecedents It would not have been possible to establish the program in 2012 without previously established relationships and collaborations. Dr O’Connell traveled to Cuba multiple times between 2001 and 2011, many of the trips associated with a community nonprofit, the Boulder–Cuba Sister City Association (Boulder, Colorado has a sister-city relationship with the municipality of Yateras in rural Guantánamo Province). During these trips, she learned about the Cuban public health system and worked on projects supported by the Cuban Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP) and the Sister City Association. Those efforts led to development of oral health educational materials and an oral health program for children, known as Alerta Feliz. Three MINSAP oral health experts created the program in partnership with Dr O’Connell and an artist from Guantánamo Province.[9] In 2008, Dr O’Connell participated in the International Congress on Health Economics, held in Havana, and initiated discussions with ENSAP colleagues about possible collaboration. During this period, representatives from the US nonprofit, Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba (MEDICC) were invited to give seminars on the Cuban public health system at the University of Colorado to increase knowledge of key elements of Cuba’s public health system among administrators, faculty and students. CSPH is part of the university system and was interested in increasing global health opportunities for its students.

Program The program was designed to foster MPH students’ understanding of factors that influence public health and public health administration in Cuba and other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. It highlights Cuba’s focus on:

- prevention and primary health care services;

- financial and geographic access, and health equity;

- continuum of care across settings that include the home, family doctor-and-nurse offices, polyclinics and hospitals, in both urban and rural areas;

- data collection at all levels to understand health risks, including outbreaks, and to guide resource allocation;

- dispensarización, or continuous assessment and risk evaluation, assessing patients’ health using a comprehensive definition of health that includes patients’ and families’ physical, mental, economic and social status, and tailors followup protocols accordingly;[4]

- multisectoral collaborations between MINSAP and other Cuban agencies and organizations to address population health risks;

- disaster preparedness, response and recovery; and

- international collaborations that include providing public health services, training, consultation and disaster relief throughout the world.

Program readings, seminars and assignments include information on health systems in Latin American and other Caribbean countries to provide context for understanding the Cuban health system.

At the end of the course students must be able to describe these countries’ population health status; assess scientific evidence relevant to health, health service delivery and outcomes; assess differences between health service delivery models; analyze policies, resources and other factors that contribute to health; and engage with Cuban faculty, students, health administrators and providers to develop understanding of these health systems.

Justification Future health professionals in the USA can gain valuable insights from examining Cuba’s health service delivery model, which focuses on prevention and primary care, evidence-based approaches, and rigorous data collection to understand and address health risks, and which has produced impressive health outcomes, despite ongoing economic difficulties and limited resources.[3−5]

Participating institutions and their contributions Program Logistics ENSAP and CSPH personnel are responsible for organizing course content at their respective institutions.[7,8] ENSAP coordinates provision of ENSAP seminars and site visits in Havana, while Cienfuegos Province’s MINSAP personnel coordinate site visits in Cienfuegos. ENSAP faculty participate in site visits in Havana and Artemisa, and ENSAP faculty members travel with the class to Cienfuegos. Cienfuegos and Artemisa were chosen because they have achieved high standards in health services organization and for logistic reasons, because they are close to Havana. ENSAP faculty provide information on specific topics addressed and their relevance to other components of Cuba’s health system. Their perspectives as national and international health experts as well as Cuban community members are invaluable.

CSPH oversees Colorado-based academic content and arranges travel logistics for students and accompanying faculty. Course content is revised by ENSAP and CSPH faculty and MINSAP personnel. For example, ENSAP and MINSAP identify opportunities to revise seminars and schedule other site visits. A CSPH anthropologist has added content to improve student understanding of demographic, social and economic factors that contribute to population health.

Collaboration mechanisms Compliance with Cuban and US government regulations and academic requirements Each year ENSAP and the University of Colorado’s Office of International Studies (OIS) update their program agreement via a signed letter. Additionally, the course’s educational objectives and content satisfy CSPH requirements for MPH academic competencies and credits. MINSAP, ENSAP and CSPH organize program logistics and activities to ensure compliance with Cuban and US government regulations. ENSAP and MINSAP oversee compliance with Cuban regulations, including arranging for US students to have Cuban academic visas. CSPH and OIS provide logistical support and oversight to ensure compliance with US regulations and mitigate risks associated with travel. As part of this effort, CSPH and OIS personnel review information on Cuba from the US Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, US Department of State, and International SOS.[10]

Activities Program Description To achieve the program’s objective, the Cuba health program is organized as a semester class, with academic learning occurring in Colorado and Cuba. The three-credit course starts in the spring semester, spans 12–14 weeks and ends in the summer semester. This schedule allows for travel to Cuba to occur after spring semester ends.

In Colorado, students apply to participate in the program. The application process includes an interview to ensure the class supports students’ academic goals. This is particularly important as the program cost, which students pay, includes tuition and costs associated with student and faculty travel (airfare, lodging, transportation, meals, etc. in Cuba). Additionally, since most students are employed, many must use vacation time to take days off from work.

Below we describe the types of students who participate in the program and academic activities in Colorado before travel to Cuba, during the 12 days in Cuba, and in Colorado upon return.

Program participants include students from a wide range of personal and professional backgrounds and experience; this diversity contributes to their learning. Most participants are students enrolled in the MPH degree program at CSPH. Students may also be enrolled in other University of Colorado academic programs in the Schools of Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Public Affairs, Liberal Arts, and Business, some of whom are dually enrolled in CSPH to obtain an MPH. Most students are employed as health professionals at local and state departments of health, health provider organizations (e.g., hospitals, clinics); as clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurses); or as administrators at university research centers or other health organizations. Thus far, four faculty from University of Colorado programs other than CSPH have participated.

Before the trip, students attend 3 seminars and complete 10–12 online educational modules that include readings, discussions and other academic content. Seminars and modules describe aspects of the public health system and MINSAP’s relationship to other governmental organizations. Modules address provision of services for specific populations such as pregnant women, children and elders; communicable diseases such as diarrheal disease, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS; and chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Other topics include workforce development, vector control (e.g., Aedes aegypti mosquito), vaccine and medication production, natural and traditional medicine, and an overview of Cuba’s history and economy.

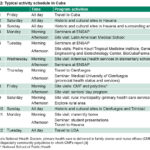

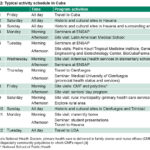

The course’s central assignment is a comparative report on how Cuba and another country in Latin America or the Caribbean address a specific public health topic. Table 1 provides an overview of topics selected to date. Before the trip, students write a short report on Cuba’s strategies for addressing their topics. The Colorado coursework provides a basic understanding of Cuba’s health system and a foundation for more in-depth exchanges with Cuban faculty, students, health providers and the community during the trip.

The trip to Cuba includes a full-time schedule (typical schedule in Table 2). During the first three days, students engage in activities to learn about Cuba’s history, economy and culture, and how social determinants of health influence service provision. The schedule includes seminars at ENSAP that build on the learning that occurred in Colorado. ENSAP faculty address the school’s educational programs; Cuba’s health care system principles, services, and transformations over time; workforce development; health statistics and disease surveillance; health promotion; research on current health priorities (including economic studies) and disaster preparedness. Faculty are national experts in their fields and students benefit from their experiences in Cuba and internationally.

The trip to Cuba includes a full-time schedule (typical schedule in Table 2). During the first three days, students engage in activities to learn about Cuba’s history, economy and culture, and how social determinants of health influence service provision. The schedule includes seminars at ENSAP that build on the learning that occurred in Colorado. ENSAP faculty address the school’s educational programs; Cuba’s health care system principles, services, and transformations over time; workforce development; health statistics and disease surveillance; health promotion; research on current health priorities (including economic studies) and disaster preparedness. Faculty are national experts in their fields and students benefit from their experiences in Cuba and internationally.

Students have opportunities to interact with Cuban health professionals who deliver services on site visits to national health institutions in Havana and health providers in other provinces. During the visit to the Latin American Medical School,[11] students learn about Cuba’s role in training physicians from other countries, as well as Cuba’s history of international assistance. Researchers at the Pedro Kourí Tropical Medicine Institute[12] provide information on their collaborations overseas and Cuba’s history of managing HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and dengue. Students learn of US collaborations with BioCubaFarma (which specializes in pharmaceutical and biotechnology research, development, production and marketing)[13] and with the Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology Center[14] from representatives who describe development and production of commonly used medications and vaccines, as well as innovative medications used in Cuba and exported.

Students start their five-day stay in Cienfuegos Province at the Medical University of Cienfuegos, where faculty provide an overview of provincial population health status, health services and medical training programs. In Cienfuegos City, students visit four key health care providers: a family doctor-and-nurse office (CMF), a polyclinic, a maternity home and a seniors’ day center. One day is spent in a rural municipality to observe how primary health care services are delivered there. During these urban and rural site visits, students learn how health care facilities coordinate services between various levels of care while addressing their communities’ environmental and occupational risks, including those associated with vector control and disasters.

During seminars and site visits in Cuba, students obtain information on the specific health topics each is researching. Because students have basic background information, we all benefit by their insightful questions about those topics. One program highlight for class instructors is the seminar scheduled toward the end of the trip when students give presentations on their topics (synthesizing information they obtained before and during the trip), discuss their findings and ask remaining questions. Cuban health care providers and community members also participate in the seminars, offering their perspectives and contributing to the question-and-answer period.

Accompanying CSPH faculty members are particularly intent on developing critical thinking among students by encouraging them to ask key questions, not only about the achievements and advances but also about the challenges Cuba’s health system faces in for taking a deeper look into both Cuba’s and comparison-country health systems.

When students don’t have a scheduled activity, they learn about public health through interactions with Cubans in the community and by exploring their surroundings. For example, they are able to obtain a community perspective on the complexities of specific health issues (e.g., nutrition, exercise, aging), hurricane preparedness and mosquito control. Upon return to the USA, students incorporate what they learned in Cuba in their final reports, in which they share highlights of their comparisons between the two countries selected, during presentations given in the last class seminar, a few weeks after their return.

Although each activity makes its unique contribution to the course, CMF visits considerably expand students’ understanding of primary health care. Students directly observe one of the few health care systems that has fully implemented community-based primary health care. They learn first hand from family doctors and nurses about services delivered in their neighborhoods in collaboration with other providers, have an opportunity to walk through a neighborhood with a family doctor to conduct a home visit and discuss a variety of health topics with doctors, nurses and patients.

Outcomes To date, 49 individuals have participated in the program (45 students, 4 faculty). Students demonstrate their understanding of factors influencing public health and resource allocation for health services through verbal communication, online discussions, class presentations and written reports. As described above, the central course assignment is a report on how Cuba and another country in Latin America or the Caribbean address a specific public health issue. A grading rubric is shared with students and used to give them written and verbal feedback on drafts. The rubric and feedback support students’ ability to demonstrate competencies related to program objectives; the vast majority of students demonstrate high competency levels. More information about the course and types of student assessment used to determine their course grade may be obtained on the CSPH website.[15]

Students provide comments about the course throughout the class and through course evaluations. In morning planning and afternoon debriefing sessions during the trip, students have opportunities to discuss program activities and make suggestions. At the end of the course, students submit anonymous evaluations that include open-ended questions and use of a 5-point scale (1 = needs much improvement, 5 = excellent) to provide feedback on specific class components. To date, the overall course rating is 4.6.

Students provide comments about the course throughout the class and through course evaluations. In morning planning and afternoon debriefing sessions during the trip, students have opportunities to discuss program activities and make suggestions. At the end of the course, students submit anonymous evaluations that include open-ended questions and use of a 5-point scale (1 = needs much improvement, 5 = excellent) to provide feedback on specific class components. To date, the overall course rating is 4.6.

At the end of each year, MINSAP, ENSAP and CSPH personnel involved conduct an informal evaluation of program activities and the institutions’ respective contributions to program objectives. We revise the Cuba program based on faculty and student evaluations. Online course content now includes a greater emphasis on economic evaluation and resources allocated to health service provision, because of the importance assigned these issues in Cuba. ENSAP faculty now include more practical applications of key Cuban public health concepts, programs and outcomes in seminars. Over the years, we have incorporated new site visits. For example, in 2017, students visited Artemisa Province to learn about provision of health education and preventive dental services in elementary schools.

ANALYSIS

Program challenges and benefits Although we encountered many challenges developing and implementing the program, due in part o political differences between our two countries, we addressed them with support from our academic institutions, aided by flexibility, persistence, good humor and friendship. As health professionals, we stayed focused on our mutual interest in providing an educational program about a health care delivery system with notable outcomes. Based on our experiences collaborating on this education program and the oral health project, we appreciate the importance of ongoing communication between US and Cuban colleagues to improve understanding of each institution’s goals and objectives, address all aspects of the collaboration, comply with US and Cuban regulations, and become aware of and allow time to address changes.

Students encounter challenges related to language and costs. Students who do not speak Spanish or Portuguese are not able to access health information published in Cuban and other academic journals. However, much information on Cuba’s health system is available in English language journals (e.g., The Lancet, American Journal of Public Health, MEDICC Review) and in reports from PAHO, WHO and other international agencies. Although translation is provided for seminars and site visits, opportunities for additional conversations in small groups are more limited for these students.

Over the years, Colorado and Cuban faculty have identified opportunities for additional collaborations, based on faculty expertise and interests and a desire to expand opportunities for students at both institutions. A challenge limiting such activities is the availability of financial support; e.g., Colorado students wishing to pursue additional educational activities (e.g., independent studies, practicums, capstone projects) require funding for travel in addition to Cuban and Colorado institutional approvals. Nonetheless, such activity is occurring.

In addition to earning credits toward their degree programs, students benefit from the program in numerous ways in the short and long term. Some students’ academic programs include a global health concentration and learning from this program will contribute to their future studies and work. For example, a doctoral student is using knowledge obtained from the class in her dissertation research. The program gives future US health professionals opportunities to engage with Cuban faculty and health care providers on Cuba’s health system model and provision of specific services. Despite differences between the US and Cuban health systems, many lessons learned from Cuba are applicable to addressing US health needs. Students learn about home visits, comprehensive health assessment and cross-sectoral coordination of services—concepts that are increasingly being applied in the USA to address a broad array of health issues, including mental health.

MINSAP, ENSAP and CSPH have also derived benefits from this collaboration, including academic exchanges in both countries that facilitate learning about health systems and research methods. For example, funds were secured to support three ENSAP faculty visits to the University of Colorado, where they gave seminars and discussed their research and education programs with peers. Additionally, CSPH faculty have given papers and participated in roundtables at international health conferences held in Cuba and have had exchanges on qualitative and quantitative research methods (including those associated with economic studies) with ENSAP faculty.

Through in-person meetings and email, ENSAP and CSPH faculty have collaborated with MINSAP as the Alerta Feliz oral health education program is revised and deployed to other locations. During the 2017 site visit to Artemisa Province, Colorado students learned about research on the Alerta Feliz program conducted by dentists in ENSAP’s master of health economics program. The research objective was to improve children’s oral health practices, using Alerta Feliz program concepts and materials. CSPH faculty are advisors to this work, providing information and guidance on research methods and oral health.

An important limitation of this endeavor is the course’s short duration, which limits the number of field activities and topics covered. This is partially offset by pre- and postcourse assignments required of participants.

A key message of the course is that experiences and methods cannot be extrapolated from one scenario to another but must be critically assimilated. Political, economic and cultural factors influence strategies to implement programs and policies and modify intervention effects.

ENSAP and CSPH faculty learn educational methods from each other. For example, ENSAP learned methods for integrating practice and research into student seminars. Furthermore, ENSAP faculty and MINSAP personnel have an opportunity to deepen their understanding of Cuba’s health system through the program activities and engagement with each other, as well as CSPH faculty and students. Throughout the trip, CSPH faculty improve their Spanish language skills and conversely, Cuban faculty improve their English.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge support from faculty and administrative personnel at MINSAP in Havana and Cienfuegos, ENSAP, CSPH and OIS. The national institutions and health care providers we visit warmly welcome students while providing valuable information. We value their time spent away from patients and other activities. Finally, the class could not be offered without the translators’ skill and expertise.

References

- Reed G. Charting the Course to Universal Health in the Americas: Cristian Morales PhD, PAHO/WHO Representative in Cuba. MEDICC Rev. 2016 Jul;18(3):6–8.

- Campion EW, Morrissey S. A different model–medical care in Cuba. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 24;368(4):297–9.

- de Andrade LO, Pellegrini Filho A, Solar O, Rígoli F, de Salazar LM, Castell-Serrate P, et al. Social determinants of health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development: case studies from Latin American countries. Lancet. 2015 Apr 4;385(9975):1343–51.

- Keck CW, Reed GA. The curious case of Cuba. Am J Pub Health. 2012 Aug;102(8):e13–22.

- Pan American Health Organization. Core Indicators. Health Situation in the Americas 2016. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2016. 20 p.

- S. Department of the Treasure, Office of Foreign Assets Control. 2011. Code of federal regulations, Title 31 – Money and Finance: Treasury, Part 515- Cuban Assets Control Regulations, Section 515.565 Educational activities. Federal Register. 2011;76(19):5075–6.

- National School of Public Health (CU) [Internet]. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); c2017 [cited 2017 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.ensap.sld.cu/. Spanish.

- Colorado School of Public Health [Internet]. Colorado: University of Colorado; Colorado State University; University of Northern Colorado; c2018 [cited 2017 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/PublicHealth

- Sala Adam MR, Sardina Alayon SE, Orbay Arana MC; Ministry of Public Health (CU), National School of Public Health. Alerta Feliz, Para una Sonrisa Saludable. Denver: Signal Graphics Printing; 2013. Spanish.

- International SOS [Internet]. Philadelphia: International SOS; c2018 [cited 2018 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.internationalsos.com/

- Latin American Medical School [Internet]. Havana: ministry of Public Health (CU); c2017 [cited 2017 Sep 29]. Available from: http://instituciones.sld.cu/elam/. Spanish.

- Pedro Kourí Institute of Tropical Medicine [Internet]. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); c2017 [cited 2017 Sep 27]. Available from: http://instituciones.sld.cu/ipk/

- Biotechnological and Pharmaceutical Industries Group (BioCubaFarma) [Internet]. Havana: BioCubaFarma; c2017 [cited 2017 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.biocubafarma.cu. Spanish.

- Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology [Internet]. Havana: Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology; c2018 [cited 2017 Jan 8]. Available from: http://www.cigb.edu.cu. Spanish.

- Colorado School of Public Health [Internet]. Denver: University of Colorado; c2018. Community & Behavioral Health; [cited 2018 Mar 20]. Available from: http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/PublicHealth/Academics/departments/Communi

tyBehavioralHealth/About/Faculty/Pages/OConnellJ.aspx

- Anuario de la Unidad Central de Colaboración Médica. V Aniversario. Las historias de la Colaboración Médica Internacional de Cuba [Editorial]. Unidad Central Colab Médica. 2015;5(2):6–7. Spanish.

- Keck CW. The United States and Cuba — Turning Enemies into Partners for Health. New Engl J Med. 2016 Oct;375(16):1507–8.

- Roswell Park Comprehensive Care Center (US) [Internet]. New York: Roswell Park Comprehensive Care Center; c2018. CIMAvax Lung Cancer Vaccine; [cited 2018 Jan 8]. Available from: https://www.roswellpark.org/cancer-vaccine

- World Health Organization. Cuban experience with local production of medicines, technology transfer and improving access to health [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2015 [cited 2017 Sep 27]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21938en/s21938en.pdf

THE AUTHORS

Joan O’Connell (Corresponding author: Joan.OConnell@ucdenver.edu), health economist with a master’s degree in health sciences and a doctorate in economics. Associate professor, Department of Community and Behavioral Health and Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health, Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado, Aurora (CO), USA.

Ana María Gálvez-González, health economist with a doctorate in health sciences. Professor and chair, Department of Economics, National School of Public Health (ENSAP), Havana, Cuba.

Jean Scandlyn, medical anthropologist with a doctorate in anthropology. Associate clinical professor, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado, Denver (CO), USA.

María Rosa Sala-Adam, dentist with a master’s degree in health promotion; 30 de Noviembre Community Polyclinic; assistant professor, Department of Social Sciences, ENSAP, Havana, Cuba.

Xiomara Martín-Linares, economist with a master’s degree in medical education. Adjunct professor and director, International Relations Department, ENSAP, Havana, Cuba.

Submitted: October 17, 2017 Approved: April 18, 2018 Disclosures: None