ABSTRACT

Cuba has one of the fastest aging populations in Latin America and the Caribbean (20.4% of the population aged ≥60 years by 2018) and life expectancy has climbed to nearly 79 years. This demographic shift has prompted a number of initiatives to address the needs of older adults and promote active, healthy longevity.

At the community level in Cienfuegos Province, an educational program was implemented designed to foster a more active role in society for older adults and improve their quality of life upon retirement, as well as to reinforce a positive culture of aging. The program ran from June 2010 to June 2018 in the Mental Health Department of the Dr Enrique Barnet Polyclinic in the Santa Isabel de las Lajas Municipality. Twenty-two groups were constituted of 330 older adults who were trained for 10 weeks in techniques of self-awareness, personal growth, development of social skills, use of social support networks, adoption of healthy lifestyles and formulation of retirement plans. Results were assessed for each group one year after program completion and the information summarized.

Participants whose definitions of “older adult” and “retirement” were rooted in nondiscriminatory concepts increased from 53 to 303 and retirees not incorporated into active social/economic life decreased from 228 to 36. At the outset, only 22% had coping mechanisms to manage their new role as retirees and 9% had a life plan for retirement. One year after finishing the program, 318 (96%) reported they were prepared to face this new stage in their lives and 294 (89%) had completed life plans; at the start, 116 (35%) were taking antidepressants and one year later, 103 of them had reduced or eliminated the drugs. The program enriched participants’ culture of aging, as well as relationships with their families and their communities.

KEYWORDS Retirement, aging, community health planning, Cuba

INTRODUCTION

Cuba has one of the fastest aging populations in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 1999, 13% of the population was aged ≥60 years, while by 2018, this proportion had climbed to 20.4%. Meanwhile, life expectancy has risen to nearly 79 years.[1–3]

This demographic shift demands attention from all of Cuban society and from the health system in particular, aimed at improving quality of life for older adults. This has prompted initiatives at the community level to address the financial, social and cultural needs of this population; promote their social and family inclusion; foster their active role in society; and continue to ensure their safety, health and wellbeing.

Within the older-adult population, retirees face a particular set of issues, since retirement has major consequences that alter the life course. The change in status from active participant in the labor force to retiree occurs in phases, which begin before retirement and continue well beyond.[4–7] We do know that adjustment to and satisfaction with the retirement process is greater among those who have prepared for this new stage, while those who did not prepare have reported greater dissatisfaction and difficulty adjusting.[8,9]

In Cuba, Social Security Law 24/79 (in effect 1979–2008) set a minimum retirement age at 60 years for men and 55 for women.[10]

IMPORTANCE The Educational Program for Retiring Persons has been under way for nine years in one community setting. Results indicate it has promoted a culture of aging that includes active retirement and improved quality of life in adults aged ≥60 years. As a result, the Program has been extended to several municipalities in Cienfuegos Province, central Cuba.

In 2009, Social Security Law 105/08 increased the minimum retirement age for men to 65 and to 60 for women, with a 5-year transition period, during which the retirement age was gradually increased until reaching those set by the new law.[11] On average, Cubans will live between 13 and 20 years after the set retirement ages (although retirement is not obligatory), taking into consideration the differences in life expectancy between men and women (men at 76.50 years and women at 80.45).[2]

This paper describes a community-based program in the Santa Isabel de las Lajas Municipality in central Cuba’s Cienfuegos Province. On the program’s start date in 2010, the municipality’s working age population was 12,504, 5625 women (45%) and 6879 men (55%); 9581 (76.6%) were employed, of whom 3079 (32.1%) were women. By 2019, the total working age population had risen to 15,111, of whom 6394 (42.3%) were women. Of the 7986 employed (52.8%), 3851 (48.2%) were women. In 2010, there were 4160 adults aged ≥60 years (20.1% of the population); by 2019, this had increased to 5031 (22.7%). Among adults aged ≥60 years, the respective proportions of women for 2010 and 2019 were 50.2% and 50.8%. There were 2488 retirees in the municipality in 2010 and 3532 in 2019 (53% men, 47% women). In 2010, there were 386 actively employed persons aged ≥60 years; in 2019, there were 867.[12]

Intervention universe, design and recruitment The program was designed for persons who either reached retirement age or retired during a one-year period before or after the program’s start in 2010 and was implemented in three stages. The first stage, program planning, was carried out in 2010; the second, program implementation, was developed from 2010 to 2017; and the third, program assessment, began one year after the first group concluded the program in 2011 and lasted until 2018, one year after the last group ended the program. It was carried out in the Mental Health Department of the Dr Enrique Barnet Polyclinic in Santa Isabel de las Lajas Municipality, a community-based multi-specialty health center serving the surrounding health area. The program was authorized by the Santa Isabel de las Lajas Municipal Public Health Department and each retiree provided written informed consent to participate.

The universe consisted of 356 retirees of both sexes, all of them residents of the health area served by the Dr Enrique Barnet Polyclinic, who were organized into 22 groups from June 2010 to June 2018. Of these, 330 completed the program and 26 left for various reasons; of those completing the program, 221 (67%) were women. Each group included 15–20 participants of both sexes. New members were not added to a group once its activities had begun. The program consisted of ten two-hour sessions, held once a week for ten weeks. The Labor and Social Security Office of Santa Isabel de las Lajas supplied the retirees’ information and location records, issued in the period from June 2010 to June 2018.

Inclusion criteria Individuals who reached retirement age (according to Social Security Law No. 24/79 and No.105/08) or who had retired within one year before or after each group began its activities, and provided informed consent to participate.

Exclusion criteria Individuals who retired due to total disability (as stipulated in Social Security Law No. 24/1979 and No. 105/08) or partial disability (as stipulated in Resolution 6 of Social Security Law No. 24 /1979); persons with an intellectual disability or severe cognitive impairment who were unable to express their wishes; and individuals who refused to join the study.

Reasons for loss to followup Emigration: 20, death: 6.

Program planning The program was based on a diagnostic study of main factors influencing adjustment to retirement, which included 164 retired seniors. These persons would later enroll in the first of the program’s 22 groups. During this stage, participating health professionals learned from the retirees about their problems, how they perceived retirement, and how they wanted to change their lives to approach it more positively. To collect this information, individuals completed a questionnaire after receiving an explanation of program objectives.

This diagnostic tool consisted of 43 sections with closed- and open-ended questions, approved by the Scientific Council and Ethics Committee of the of Santa Isabel de las Lajas Municipal Public Health Department. It was based on an extensive review of the literature on retirement. To evaluate its reliability, the questionnaire was applied to the same group of retirees twice, the second time four weeks after the first, to measure stability over time. This comparison was done using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, using the usual cutoff point for reliability of 0.80.

Two aspects of the questionnaire’s validity were assessed. Its construct validity was evaluated through principal component analysis. When the information collected can be summarized by a few linear combinations of the original variables, the questionnaire is considered consistent. Content validity was evaluated by ten specialists, each with at least two years’ experience working with seniors and retirees in three municipalities (Santa Isabel de las Lajas, Cruces and Palmira), all in Cienfuegos Province. The content of each section was rated according to Moriyama’s principles.[13]

The validated questionnaire was administered to participants in each of the 22 groups during their first session to learn about their expectations of the program and to eventually adapt the questionnaire to the specific needs of each group. It was readministered during the groups’ last session to learn how well the program met expectations.

We assessed the availability of qualified staff and material resources in the municipal Mental Health Department and identified community institutions and social support networks whose directors and employees were willing to help implement the program.

Program implementation The program used therapeutic and participatory techniques, presentations and dramatizations, experiential techniques, audiovisual methods, discussions of cases and situations/problems, and information-sharing and interactive techniques, as well as methods aimed at greater self-control and personal growth. To foster family support and expand retirees’ use of social networks to implement their plans for retirement, we held sessions with relatives and visited social institutions. The latter included senior centers (day facilities for older adults, offering lunch, social and recreational activities, etc., supervised by health professionals); senior clubs (often led by family doctors, involving neighborhood seniors in exercises and other activities); and the older-adult university centers (offering continuing education opportunities at the municipal level). In each place, retirees met the institutions’ leaders/directors.

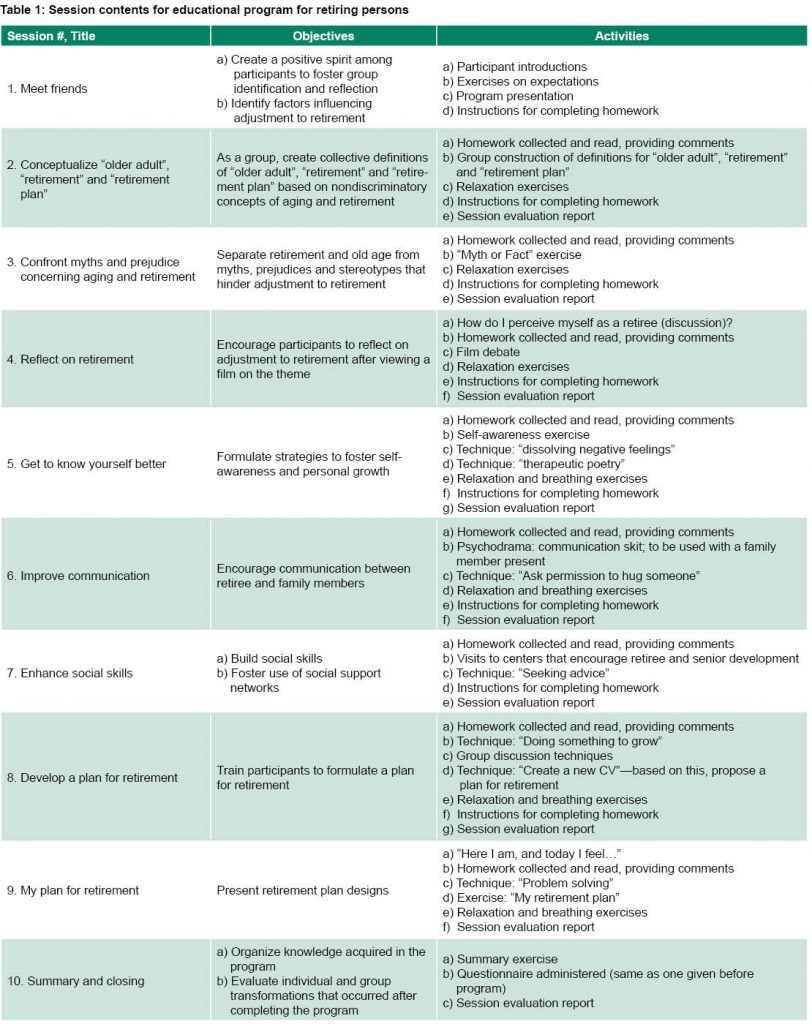

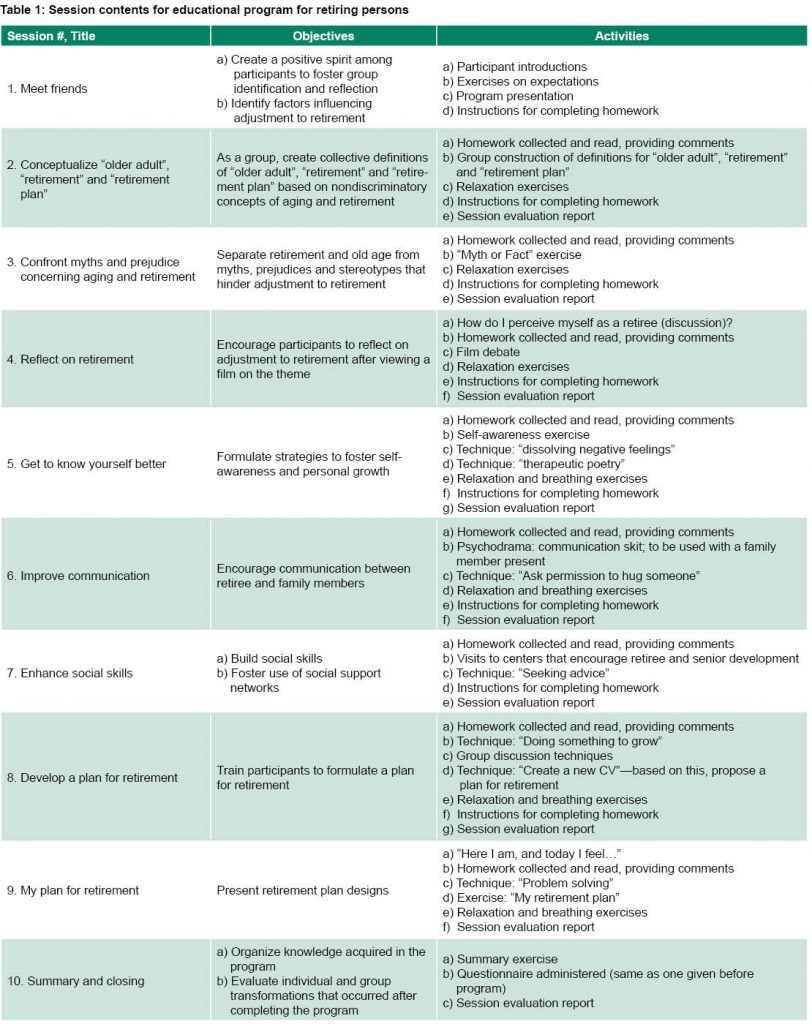

Table 1 summarizes activities in each of the program’s ten sessions.

One year after each group completed the program, a structured interview was conducted to measure the satisfaction of both participants and their families, lifestyle changes, and how participants had applied what they learned to their plan for retirement.

Participants accessed the program through human resources managers in their workplaces, in coordination with local offices of the Ministry of Labor and Social Security and the National Social Security Institute, or through family doctors, psychologists, geriatricians, social workers, community health activists and older-adult university faculty, as well as other organizations and institutions working with seniors and retirees.[14]

Trained staff, supervised by the program director, implemented the program. A psychologist from either the Mental Health Department or primary health care teams served as the main program facilitator, assisted (depending on the session) by a geriatrician, occupational therapist and social worker affiliated with the Department. All had been trained to work with seniors and retirees, including enrollment in workshops on use of participatory techniques and the Comprehensive Elder Care Course, the latter approved by the Santa Isabel de las Lajas Municipal Public Health Department’s Scientific Council.

PROGRAM RESULTS AND LESSONS LEARNED

Although men outnumber women among the municipality’s 3532 retirees (in 2019, 53%), most program participants were women (221, 67%). This result bears monitoring in any extension of this program, given potential implications for advancing goals of greater social inclusion and satisfactory aging.

At the program’s start, sociocultural, family and individual factors were observed that could adversely affect adjustment to retirement. As sessions developed, retirees worked together in their groups to construct definitions of “older adult” and “retirement” based on nondiscriminatory notions, discussed how to apply these in their daily lives and received training in self-control, relaxation and breathing exercises, among other activities. The structured interview, conducted one year after each group completed the program, assessed participant satisfaction with what they had learned and its application to their plan for retirement. Among the most salient results, as declared in the interview, were:

Participants with nondiscriminatory definitions of “older adult” and “retirement” increased from 53 (16%) to 303 (92%). Retirees with active social participation increased from 102 (32%) to 294 (89%). Of these, 190 (57%) were participating in two or more activities (119 women and 71 men); 104 (32%) were participating in one activity (74 women and 30 men). Stated differently, the number of those who had not changed lifestyles and remained more socially isolated decreased from 228 (69%) to 36 (11%) (28 women and 8 men).

Among the 294 engaged in active social life one year after completing the program, retirees engaged in farming increased from 34 (12%) to 76 (26%); 65 (22%) had returned to work in the education sector, 24 (8%) in the health sector; 85 (29%) were self-employed—food vendors, florists, seamstresses, tobacco selectors, carpenters, craft vendors and caregivers for children and the elderly; 141 (48%) were providing (unpaid) support to family at home by caring for grandchildren and dependent elders; 112 (38%) had joined senior clubs where they practiced physical exercise (data verified with the clubs); 132 (45%) were taking older-adult university classes; 135 (46%) had joined in recreational activities organized by community institutions; 44 (15%) reported a more active social life, visiting friends, family or places of cultural or recreational interest; 32 (11%) were participating in religious activities; and 42 (14%) were involved in sports clubs.

Improved family communications, more balanced division of household work and support for new retirement plans were also reported. Strengthening family relations was aided by participation of 259 (78%) family members invited to specific sessions. Retirees whose families did not participate were enrolled in senior-center programs. Of the 188 retirees who described an overload of household tasks, 115 (61%) reported improvements at year’s end—a factor that may have facilitated the greater social incorporation also reported by many participants.

At the program’s start, only 22% of participants said they had coping mechanisms in place to address life changes implied by retirement and only 9% had a plan for retirement. One year later, 318 (96%) participants reported feeling motivated and prepared to face this new life stage, and 294 (89%) had a developed a plan for retirement. Among the program aspects contributing most to these changes, 303 (92%) named personal growth and acquisition of social skills to address aging; 294 (89%) mentioned creation of a retirement plan, adoption of healthy lifestyles, such as care for physical well-being, exercising and options for use of free time;[14] and 261 (79%) noted that the program strengthened their social skills for relating to people outside the group and added personal resources to facilitate both self-awareness and personal growth as well as to overcome negative emotional states.

At the program’s start, 116 (35%) participants were taking anti-depressants; one year later, depression morbidity had decreased and 103 (31%) had appreciably reduced or eliminated their intake of such medications, according to our communication with specialists in geriatrics and psychiatry in the health/catchment area served by the Dr Enrique Barnet Polyclinic in Santa Isabel de las Lajas. We hypothesize that the psychological coping mechanisms and lifestyle changes acquired during the program may have offset more negative biopsychosocial changes characteristic of this life stage.

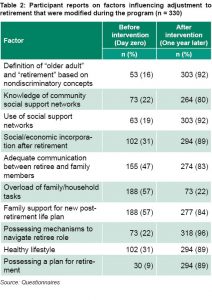

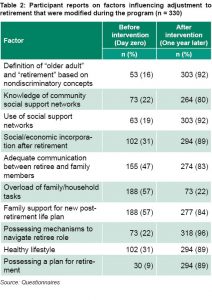

Table 2 compares a number of self-reported participant variables, before and one year after program completion, illustrating changes perceived.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FURTHER STUDY AND ACTION

The team of health professionals involved in the program gained experience in working with retirees and benefited both professionally and personally. Participating professionals reported that the program spurred actions for community-engaged health promotion and disease prevention, and created a place for retirees to obtain information and guidance about municipal institutions and support networks, as well as their purpose, usefulness and how to access them. They identified the need to find new ways for people to get involved in community social and cultural activities and to create new intergenerational community development projects to pass on craft, culinary and artistic traditions, among others, allowing retirees to become more socially involved.

The program was submitted in response to the 2018 National Call for Health Research and was approved for inclusion in the National Program for Research on Health Determinants, Risks and Prevention in Vulnerable Groups, coordinated by the Ministry of Public Health’s National Hygiene, Epidemiology and Microbiology Institute. In January 2019, the program was extended throughout health care institutions in the Santa Isabel de las Lajas and Cruces Municipalities of the province, and in May 2019, it began operating among retiring workers at the Cienfuegos thermoelectric plant and the Dr Gustavo Aldereguía Lima University Hospital, both in Cienfuegos Province.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Omar Frómeta Rodríguez MS for his help in conducting interviews.

References

- World Economy Research Center (CU). Investigaciones sobre el desarrollo humano y equidad en Cuba, 1999 [Internet]. Havana: United Nations Development Programme; 2000 [cited 2019 Jun 20]. Available from: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20191016055729/Investigacion_sobre_desarrollo_humano_y_equidad.pdf. 195 p. Spanish.

- National Health Statistics and Medical Records Division (CU). Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2018 [Internet]. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 30]. 206 p. Available from: http://files.sld.cu/bvscuba/files/2019/04/Anuario-Electrónico-Español-2018-ed-2019-compressed.pdf. Spanish.

- National Bureau of Statistics and Information (CU). El Envejecimiento de la Población Cubana 2018 [Internet]. Havana: Centro de Estudios de Población y Desarrollo. Havana: 2019 Mar [cited 2019 Jun 30]. 42 p. Available from: http://www.one.cu/publicaciones/cepde/envejecimiento/envejecimiento2018.pdf. Spanish.

- Aguilera Velasco MA. Intervención socioeducativa para la preparación de la jubilación en los adultos mayores. RCSO [Internet]. 2013 Mar 1 [cited 2019 Jun 30];3(1):3–4. Available from: https://revistas.unilibre.edu.co/index.php/rc_salud_ocupa/article/view/4849.

- Martínez López AR, Soriano Ayala D, Vásquez Mancía YJ. Propuesta de programa psicoeducativo dirigido a facilitar el proceso de adaptación psicosocial para empleados del ministerio de educación de la departamental de San Salvador que se encuentren en período de jubilación [thesis] [Internet]. [El Salvador]: University of El Salvador School of Sciences and Humanities, Psychology Department; 2016 Sep 27 [cited 2019 Jun 30]. 135 p. Available from: http://ri.ues.edu.sv/12619/1/14102996.pdf. Spanish.

- Sahagún Padilla MA, Hermosillo de la Torre AE, Selva Olid C. La jubilación, hito de la vejez: revisión de aproximaciones psicosociales recientes. Quaderns de Psicología [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2019 Jun 30];16(2):27–41. Available from: https://www.quadernsdepsicologia.cat/article/view/v16-n2-sahagun-hermosillo-selva. Spanish.

- Campos González B, Escobar Fuentes D. Jubilación/Retiro Laboral: Un Estudio Exploratorio. Seminario para optar al título de Ingeniero Comercial, Mención Administración [Internet]. Santiago de Chile: University of Chile, School of Economy and Business; School of Economy and Administration; 2014 Jul [cited 2019 Jun 30]. 122 p. Available from: http://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/116641/Tesis%20Jubilaci%C3%B3n%20-Retiro%20Laboral.pdf?sequence=1. Spanish.

- Ministry of Justice (CU). Asamblea Nacional del Poder Popular. Ley No.105/08 de Seguridad Social. Gaceta oficial de la República de Cuba No. 004 [Internet]. Havana: Ministry of Justice (CU); 2009 Jan 22 [cited 2019 Jun 30]. p. 15–25. Available from: http://www.trabajadores.cu/documento/ley-105-de-seguridad-social/.

- Jiménez GC. Jubilación, ¿Premio o castigo? Alternativas para las personas jubiladas en las zonas rurales [Internet]. Salamanca: University of Salamanca; 2014 [cited 2019 Jun 30]. 19 p. Available from: http://casus.usal.es/blog/ep2015/files/2015/12/Borrador-de-Carmen-Jimenez.pdf. Spanish.

- National Assembly of People’s Power (CU). Ley Nº 24/ 1979 de Seguridad Social [Internet]. Havana: National Assembly of People’s Power; 1979 [cited 2019 Jun 30]. 25 p. Available from: http://www.sld.cu/galerias/pdf/sitios/insat/l-24-1979.pdf. Spanish.

- Monreal-Bosch P, Perera S, Martínez González M, Selva C. La percepción del colectivo médico sobre la gestión del proceso de desvinculación. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2017 Aug 21 [cited 2019 Jun 30];33(8):e00041915. Available from: https://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?pid=S0102-311X2017001005010&script=sci_arttext&tlng=es. Spanish.

- National Bureau of Statistics and Information (CU). Anuario Estadístico. Cienfuegos 2016. Lajas [Internet]. Havana: National Bureau of Statistics and Information (CU); 2017 [cited 2019 May]. 130 p. Available from: http://www.onei.gob.cu/sites/default/files/anuario_est_municipal/04_lajas_0.pdf. Spanish.

- Moriyama IM. Indicators of social change. Problems in the measurements of health status. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; 1968. 593 p.

- Ponce Laguardia TM, Matheu Jiménez D, Díaz Mora O, Cruz Cruz CA, Cabrera Parodis GM, Fernández Quintero N. Impacto de la implementación de un programa educativo de preparación de los trabajadores para la jubilación. Rev Cubana Salud Trabajo. 2017 [cited 2019 Jun 30];18(2):21–5. Available from: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/revcubsaltra/cst-2017/cst172d.pdf. Spanish.

THE AUTHOR

Tania Maité Ponce-Laguardia (taniapl710823@minsap.cfg.sld.cu), psychologist. Assistant professor with a master’s degree in satisfactory longevity, Medical University of Cienfuegos and director of the Educational Program for Retiring Persons described in this paper.

Submitted: July 02, 2020 Approved: January 18, 2020 Disclosures: None