Just over 25 years ago, when volunteers returning from international service in Africa showed signs of a mystery illness, Cuban health authorities acted swiftly and decisively. Their response was modeled on classic infectious disease control and included an epidemiological surveillance system, contact tracing and screening of at-risk groups and blood donations, accompanied by intensive research and development. The first AIDS-related death occurred in April 1986 and a policy of mandatory treatment in sanatoria was established, thought to be the most effective way of delivering the comprehensive medical, psychological and social care needed, and limiting the spread of the disease.[1] The sanatorium policy was harshly criticized by global media, human rights advocates, and some public health specialists.

As scientific data emerged elucidating the pathology of the disease, public health understanding and Cuban policy evolved with it. As of 1993, an ambulatory care system made sanatorium treatment an option rather than an obligation.[1] By then, thanks to the global introduction of antiretrovirals (ARV) in 1987, AIDS was no longer assumed a death sentence. Cuba’s challenge at the time was to find the funds to afford costly medications, and simultaneously turn more attention to nationwide prevention. The pro-active incorporation of people living with HIV in educational campaigns organized within the National HIV/AIDS Program—most notably the founding of the AIDS Prevention Group (GPSIDA, its Spanish acronym) by patients in Havana’s Santiago de Las Vegas Sanatorium in 1991—underscored this effort. Over two decades later, UNAIDS has lauded Cuba for its “exceptionally low 0.1% prevalence rate,”[2] and low rate of AIDS-related mortality.[3]

Still, despite systematic efforts to contain the spread of the disease and improve quality of life for those living with it, HIV/AIDS continues to present serious challenges to the Cuban health system and the country’s at-risk populations.

HIV/AIDS in Cuba: The Current Picture

Today, the pathways of HIV/AIDS in Cuba are different from other countries in some respects: transmission by intravenous drug use is extremely rare, as is infection from blood or blood derivatives, all of which are screened. Rates of mother-to-child HIV transmission are negligible.

In Cuba, HIV is largely urban and male, with 99% of cases contracted through sexual relations. The epidemiological profile of infection has shifted from early predominance of heterosexual transmission to that of men who have sex with men (MSM), who now constitute over 80% of people living with HIV in the country. Provinces with the most new cases in 2010 were Havana City, Isle of Youth (special municipality), Havana, and Cienfuegos.[4]

HIV prevalence in Cuba is slowly increasing, partly because people with HIV are living longer. However, more worrisome is the fact that incidence is also increasing: from 13.9 to 16.2 per 100,000 population between 2009 and 2010. Recent national surveys relate low risk perception and social constructs such as machismo to increases in HIV infection in Cubans under age 49.

HIV/AIDS in Cuba, 1986–2010

Source: Pedro Kourí Tropical Medicine Institute data, 2011

Selected HIV/AIDS Indicators in Cuba, 2009 & 2010

Source: Pedro Kourí Tropical Medicine Institute data, 2011

Cuba provides comprehensive care to all people living with the disease, and guarantees antiretrovirals (ARVs) for those needing them. Despite deep financial difficulties, treatment in Cuba, including medication, is free. In 2003, Cuba achieved universal antiretroviral therapy with domestically-manufactured ARVs for patients meeting international clinical criteria. In 2010, over 5,600 people received ARV therapy in Cuba, more than a 10% increase from the previous year.[4] The Cuban government estimates it costs US $6000 annually to treat each person with HIV/AIDS.[5]

A strategy to further decentralize services for HIV/AIDS counseling, testing, treatment and support groups was begun in 2005. Establishing and equipping additional clinical microbiology and pathology laboratories, locating specialized services in Havana City, Villa Clara, Sanctí Spíritus, Holguín, and Santiago de Cuba provinces, and closing 11 sanatoria deemed superfluous are results of this strategy, designed to improve access.

The decentralization process is slow however, and requires financial and human resources that aren’t always available. A chronic challenge in Cuba, resource scarcity in the fight against HIV is addressed by prioritizing vulnerable groups and localities, strengthening intersectoral strategies at the provincial and municipal level, and strategically channeling aid from international organizations including the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Unfortunately, the global financial crisis means these and other large organizations have fewer funds to apportion as they compete for shrinking commitments from donor countries.[6]

Nevertheless, ARV availability and such decentralization are factors that have translated into a low AIDS-related mortality rate in Cuba—between 1.5 and 1.7 per 100,000 population annually for the period from 2008 to 2010. Hidden within these statistics however, is a troubling detail: in 2010 alone, over 25% of AIDS-related deaths were people presenting with AIDS without prior HIV diagnosis.[4] In other words, despite free, universal and increasingly accessible life-extending treatment and care, people are becoming ill before being diagnosed as seropositive. Stigma, another challenge in HIV management and control, has been identified by health professionals as one reason these people don’t seek the help they need in time.

The National HIV/AIDS Program Today

Cuba’s universal public health system and a coordinated national strategy spanning prevention, detection, treatment and supportive care, help facilitate disease control. The country’s robust biotechnology sector, utilizing a closed-loop strategy prioritizing research, development and manufacture of products that directly impact population health, is another pillar of the country’s integrated approach. Active screening and contact tracing contribute to positive outcomes in the country’s fight against HIV/AIDS; in fact, more than 30% of Cubans with HIV have been diagnosed via this method.[7]

Today, intersectoral approaches and more targeted prevention are cornerstones of new initiatives to reduce HIV infection.

An intersectoral strategy Coordinating programs across sectors—including health, education, and the mass media—is the job of the multidisciplinary Working Group for Confronting and Fighting AIDS (GOPELS, its Spanish acronym). Founded in 1986, GOPELS’ work is complemented by the Ministry of Public Health’s National HIV/AIDS Program established the same year. Together, these groups oversee implementation of the National Strategic Plan for Sexually-Transmitted Infections (STI)–HIV/AIDS, 2007–2011.[8]

This strategy emphasizes work across a broad spectrum of institutions and entities: for example, the Federation of Cuban Women carries out prevention and advocacy; the Ministry of Labor and Social Security ensures constitutional anti-discrimination provisions protecting people with HIV are upheld in the workplace; and the Ministry of Domestic Trade makes condoms available in bars, discos, and restaurants. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Education, together with the Ministry of Health, the National Center for Sex Education (CENESEX, its Spanish acronym), and other institutions, coordinate the National Sex Education Program in schools nationwide.

Priorities established in the Strategic Plan through 2011 include: continuing the decentralization process; improving integration of primary care services for people living with HIV; increasing active screening for new cases (especially in at-risk populations); activating municipal epidemiological sentinel sites for vulnerable groups (MSM, people engaging in transactional sex, and women of childbearing age); expanding and strengthening the national diagnostic network; increasing the supply of condoms and access to them outside health care settings; and strengthening prevention messages by involving broader sectors in the communications strategy.[8,9]

Integrated, targeted prevention In 1998, the National STI–HIV/AIDS Prevention Center was founded to design, implement and coordinate all educational and prevention activities across the country. Located in Havana, the Center is the country’s technical partner to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. Using a community-based, participatory approach, the Center carries out consultation, research, training, education, and evaluation at local, regional, and national levels. These include anonymous counseling hotlines, design and dissemination of prevention materials, free condom distribution, and HIV/AIDS-specific training for health professionals.

Key to the Center’s approach is actively involving members of vulnerable groups and people living with HIV/AIDS in program design, implementation, and evaluation. This peer-to-peer format, whereby members of the same group volunteer as health promoters, work as counselors, or distribute condoms, is considered highly effective for reaching at-risk groups.

Examples of peer-to-peer prevention activities include Carrito por la vida (Little Car for Life, a mobile counseling and condom distribution center staffed by and for youth); Línea de Apoyo (The Support Line, a hotline where an HIV-positive counselor advises callers); and Proyecto HSH (Project MSM, an activist group of men who have sex with men, providing information, condoms, and lubricants at popular gay gathering sites).

Over the last decade, CENESEX has played an increasingly active and public role in HIV/AIDS prevention, support, and research, particularly among gender and sexual minorities. Core activities include training transgender and sexual minority health promoters, designing education campaigns, and holding workshops for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Cubans and their families. In 2007, CENESEX coordinated the country’s first Day against Homophobia, now an annual intersectoral event held countrywide, featuring rapid HIV tests, free condoms, and expert panels tackling issues including sexual diversity, HIV and the family, and the media’s role in promoting health.

Taking Stock to Move Ahead

The Survey on HIV/AIDS Prevention Indicators conducted by the National Statistics Bureau’s Center for Population and Development Studies measures knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding HIV prevention among Cubans aged 12 to 49.[10] Piloted in 1996, expanded in 2001, 2005, 2006, and conducted most recently in 2009, the survey identifies strengths and weaknesses in the national prevention program in order to design more effective measures—especially for vulnerable groups.

The survey of nearly 29,000 Cubans across the country on variables such as educational level, skin color, alcohol consumption, age at time of first sexual relations, relationship status, condom use, and a variety of socio-demographic factors, indicated:

- 37% of respondents perceived some personal risk of contracting HIV;

- 78% of MSM had used a condom during their last casual sexual encounter, compared to 72% of the total sample surveyed;

- 63% of men responding and 32% of women expressed severe or moderate prejudice against MSM;

- 29% of men and 24% of women expressed severe or moderate prejudice against people living with HIV; and

- 64% of MSM and 73% of sex workers reported consuming alcohol, compared to 46% of the total sample surveyed.

Condom Use by MSM in Cuba, by Year

*Casual sex encounter is defined as a relation lasting under one year. Source: National Statistics Bureau, Survey on HIV/AIDS Prevention Indicators, 2009

The survey narrative discusses the following conclusions: personal risk perception by both male and female respondents of contracting HIV is low; condom use is more frequent among MSM than the general population and is on the rise; alcohol consumption, as reported by the country’s two most vulnerable groups, could be linked to increased risk of contracting HIV; and men who have sex with men are more likely to face prejudice than people living with HIV; and women are more open-minded towards MSM and, to a lesser extent, HIV-positive persons than men.[10] .

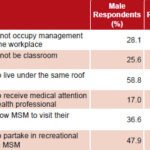

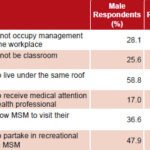

Opinions Reflecting Prejudice towards MSM

Source: National Statistics Bureau, Survey on HIV/AIDS Prevention Indicators, 2009

Opinions Reflecting Prejudice towards People with HIV

Source: National Statistics Bureau, Survey on HIV/AIDS Prevention Indicators, 2009

The challenge: raising awareness of risk Cuban HIV/AIDS experts believe success in HIV prevention and the oft-repeated statistic that Cuba has the lowest prevalence rate in the region (a real achievement—the Caribbean has the greatest HIV disease burden outside of sub-Saharan Africa) has instilled a false sense of complacency in some sectors of the population.

According to Dr Rosaida Ochoa, Director of the National STI–HIV/AIDS Prevention Center, combating this low risk perception and underscoring the disease’s severe societal impacts are key goals for 2011.[11] Targeted prevention campaigns, coordinated and strategic media coverage, and aggressive workplace outreach are tools for raising awareness. Early, comprehensive sex education including HIV prevention and sexual diversity in schools—areas where Cuba, as elsewhere, has faced challenges[12]—is imperative if young people are to internalize HIV/AIDS risk perception.

The challenge: reducing stigma Identifying low risk perception and the stigma attached to vulnerable groups is only part of the HIV prevention equation—actually changing attitudes is significantly more complex and slow to take effect. In Cuba, gender constructs such as traditional female roles and beliefs about masculine identity—especially machismo—have an impact on negotiating condom use, use of health services, and promoting confidential care in a discrimination-free and respectful environment. Such constructs also contribute to homophobia, inducing MSM to hide their sexual orientation and place themselves and their partners at potential risk.[13]

A coordinated, comprehensive strategy to combat stigma is part of Cuba’s National HIV/AIDS Program. Educational campaigns and sensitivity training in the workplace and for law enforcement officials; sexual diversity themes and the importance of condom appearing in television and radio shows, movies, and print media; and participation in the annual International Day against Homophobia, are chipping away at social constructs contributing to discrimination.

According to CENESEX Director Mariela Castro, sexual diversity is actively discussed in Cuban society and, while there are contradictions, “this signifies progress. People are learning about a reality that wasn’t talked about before. Still, there is a lot of prejudice and negativity about the work we’re doing.” One way to combat this she says is “education, education, education.”[14]

Throughout the world, constitutional provisions guaranteeing the rights of people with HIV/AIDS to health care, education and employment opportunities, and more legal instruments against discrimination, are key to protecting this vulnerable population and combating stigma. “Making the law work for the AIDS response, not against it” is one of the new frontiers for fighting the disease, says UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé.[15] Cuba, slated to debate the Gender Identity and Legal Sex Change bill this year[16] legislating similar rights for the country’s transgendered, is breaking ground in this respect.

The challenge: improving quality of life for people living with HIV/AIDS Continuing to locate diagnostic, care, and treatment services closer to those who need them through decentralization is a priority of the National Program. Maintaining adherence in a system now based primarily on ambulatory care has different challenges than one based on sanatorium care. Another related issue is guaranteeing client privacy and confidentiality—especially challenging in small towns and rural settings. Maintaining and extending specialized programs for people with HIV/AIDS—such as government-subsidized high-nutrient diets; and programs promoting self esteem and imparting life skills, such as assertiveness training, essential to sustaining responsible safe sex behavior—is another strategic area. Producing and introducing more effective ARVs is a goal that hinges on economic realities. And all of this requires a health care workforce with the training and sensitivity to deal with a range of patient needs, from emotional to biomedical.

The challenge: improving care with fewer resources Resource scarcity has been a limiting factor since the inception of Cuba’s National HIV/AIDS Program. Now the global financial crisis is restricting those resources even further, and costs of treatment continue to rise. This is compounded by the fact that international funding for global AIDS efforts remains flat. “The AIDS response was always underfunded,” says UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé, “but now the economic crisis is widening the gap and inflation is increasing the costs of delivery.”[15] Cuba is also in a uniquely difficult position due to the US embargo, which prohibits exports to Cuba of any items or inputs to be used in the domestic pharmaceutical industry. In March 2011, the United States government also blocked USD$4 million in funding from The Global Fund destined for Cuba’s National HIV/AIDS Program.[17] These economic pressures make efficient, effective strategies vital, to generate maximum results from minimum resources.

The Road Ahead

Cuba’s experience has shown that a nationally-coordinated strategy and universal access to testing and treatment are fundamental for effective HIV/AIDS management and control. Emphasizing intersectoral cooperation, involving the most vulnerable groups in program design and implementation, and rigorously evaluating program shortcomings are key to improving national efforts to sustain progress. Finally, a critical analysis of social constructs contributing to disease spread, coupled with a pro-active strategy to address these, are necessary complements to scientific evidence to effectively combat HIV/AIDS.

Furthermore, the country’s results in HIV disease prevention and management illustrate how positive outcomes can be achieved in a resource-limited setting. Analyzing the national program’s results—including best practices as well as shortcomings—could benefit similarly resource-limited settings in the Global South and elsewhere.

For more on Cuba’s HIV/AIDS national program, see Cuba’s HIV/AIDS Program: Controversy, Care and Cultural Shift in MEDICC Review, Fall 2008, Vol 10 (4).

References

- Pérez J, Pérez D, González I, Díaz Jidy M, Orta M, Aragonés C, et al. Approaches to the Management of HIV/AIDS in Cuba. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

- UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010.

- UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update 2009 [Internet]. 2009 Nov [cited 2011 Mar 21]. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/jc1700_epi_update_2009_en.pdf.

- Pedro Kourí Institute of Tropical Medicine. IPK data 2011. Havana: IPK; 2011.

- Rodríguez M. Atención integral a las personas con VIH/SIDA. Girón (Havana) [Internet]. 2011 Feb 16 [cited 2011 Mar 13]. Available from: www.giron.co.cu/Articulo.aspx?Idn=9218&lang=es. Spanish.

- The Global Fund: A bleak future ahead [editorial]. Lancet. 2010 Oct 16;376:1274.

- Estruch L, Santín M, Lantero MI, Ochoa R, Joanes J, Pérez JL, et al. República de Cuba. Informe nacional sobre los progresos realizados en la aplicación del UNGASS. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2008 Jan. Spanish.

- Ministry of Public Health (CU). Plan estratégico nacional ITS/VIH/SIDA, 2007-2011. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); Jan 2007. Spanish.

- Estruch L, Santín M, Lantero MI, Ochoa R, Joanes J, Alé K, et al. República de Cuba. Informe nacional sobre los progresos realizados en la aplicación del UNGASS. Havana [Internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010 Mar [cited 2010 June 20]. 42 p. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/cuba_2010_country_progress_report_es.pdf. Spanish.

- Centro de Estudios de Población y Desarrollo. Encuesta sobre indicadores de prevención de infección por el VIH/SIDA, 2009. Havana: National Statistics Bureau (CU); 2010. Spanish.

- Edith D. Cuba: VIH, descubrir todos los riesgos. SEMLAC Servicio de Noticias de la Mujer de Latinoamérica y el Caribe (Lima, Peru) [Internet]. 2010 Nov 29 [cited 2011 March 8]. Available from: www.redsemlac.net/web/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=824:cuba-vih-descubrir-todos-los-riesgos&catid=43:sida–vih&Itemid=62. Spanish.

- Gorry C. Transgender health in Cuba: Evolving policy to impact practice. MEDICC Rev. 2010 Oct;12(4):5–9.

- UNAIDS. HIV prevention hampered by homophobia. UNAIDS [Internet]. 2009 Jan 13 [cited 2011 March 30]. Available from: www.unaids.org/en/Resources/PressCentre/Featurestories/2009/January/20090113MSMLATAM/. Spanish.

- Castro M. Keynote speech. Primer Coloquio Internacional Trans-Identidades, Género, y Cultura. Havana; 2010 Jun 9.

- Sidibé M. Letter to partners, 2011. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011.

- Interview with Zulendrys Kindelan, 16 Sep 2010.

- Berbeo RA. Cuba denounces U.S. seizure of health funds. Juventud Rebelde (Havana) [Internet]. 2011 Mar 13 [cited 2011 March 8]. Available from: http://www.juventudrebelde.co.cu/international/2011-03-12/cuba-denounces-us-seizure-of-health-funds/.

Disclosures: None