Statistics have the capacity to startle: in Cuba, suicide is one of the top ten causes of death and 25% of people presenting in health facilities have been diagnosed with depression. Almost 25% of all Cuban adults smoke, and while smoking overall is on the decline, the figure spikes at 31% for both men and black Cubans. Meanwhile, 25% of those admitted to Cuban emergency rooms test positive for alcohol use and there’s a slow upward alcohol consumption trend among Cuban women aged 15–24 years. [1–3]

Mental disorders and substance abuse are global health problems not specific to Cuba of course—one in every five people in the United States experienced a mental health problem in 2011;[4] some one third of the world’s population smokes; and 80% of men in the developing world have consumed alcohol in their lives.[5] A cornerstone of Cuba’s health system is to implement (or improve existing) programs when the evidence argues for a more effective response. It’s not surprising then that the Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP), in an intersectoral effort that also includes Cuban families and communities, has taken measures to strengthen and broaden its national mental health program.

Mental Health Services in Cuba: the Basics

In 1995, a watershed PAHO conference in Havana marked a fundamental shift in approach to mental health services in Cuba. Entitled Reorienting Psychiatry towards Primary Care, the event called upon the region’s health systems to integrate mental health services into communities and adopt more preventive strategies. This dovetailed with the expansion of primary care in Cuba begun in 1984 with the Family Doctor-and-Nurse Program, embedding this pair of professionals in each neighborhood, a vital step in providing integrated, comprehensive primary care.[6]

“The Havana Charter of 1995 changed how our mental health services were structured,” says Dr Carmen Borrego, director of MINSAP’s national mental health services and substance abuse program. “Psychiatry as a specialty took on more urgency and began to develop in earnest. Whereas before we had a medical approach to mental health, from the mid 1990s, we began looking at the entire health picture. We adopted a more integrated approach of prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. This transformed our strategy.”

In practice, this transformation meant mental health services were now accessible at the neighborhood level. Each of the country’s 11,500 neighborhood doctor-and-nurse offices is supported by a multiservice community polyclinic (452 polyclinics throughout Cuba;[1] where patients are referred who require specialized ambulatory care. The backbone of every polyclinic is the multidisciplinary basic work group (GBT, the Spanish acronym), headed by a team leader (family physician) and incorporating other health professionals and specialties, including a supervising nurse, internist, pediatrician, OB/GYN, statistician and psychologist. The GBT provides continuous monitoring and assistance to the family doctor-and-nurse duos it supervises, including review of their annual health situation analyses—a snapshot of the neighborhood’s health.

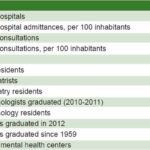

While there are 17 specialized psychiatric hospitals in Cuba (see table), post-1995, psychiatric services were also established in all general and pediatric hospitals across the country and a nationwide system of 101 community mental health centers was launched. These centers are staffed by a team of specialized nurses, psychiatrists, child psychiatrists and psychologists who offer clinical services, including psychotherapy and addiction treatment, and teach residents in the various medical specialties.

“Our goal is to provide a continuum of care. We work closely with the polyclinics and family doctors to ensure our patients receive the services they need, when they need them,” explains Dr Paula Lomba, director of the Community Mental Health Center in Guanabacoa, across the bay from Havana. Patients either walk in or are referred to community mental health centers by their family doctors, psychologists at the polyclinics or from psychiatric hospitals. Dr Lomba is quick to point out that all patients seen at any of Cuba’s mental health centers must provide written informed consent; in cases of minors or those deemed mentally incapacitated, the patient’s parents or guardians are responsible for giving consent. “We have an open-door policy and see everyone who walks,” says Dr Magalys Levya, one of the psychiatrists at the Guanabacoa center. “I see 12 to 15 people a day.”

Guanabacoa Community Mental Health Center / E. Añé

Rosa Ascaño with her hooked rug. / E. Añé

An innovation after 1995 was the introduction of ‘day hospitals’, community-based outpatient psychiatric services where people with more severe mental disorders (not requiring hospitalization) can spend weekdays. The day hospitals operate out of the community mental centers, and offer such additional services as necessary. The guiding principle is individualized care. Since you “can’t separate physical health from mental health,” Dr Lomba says, treatment includes comprehensive care for these patients—everything from an eye exam and fitting for glasses to complete dental work.

“The change was like night and day,” says 54-year-old Rosa Ascaño who had been hospitalized in a psychiatric ward for over half her life before transferring to the day hospital at Guanabacoa five years ago. “I stick to my treatment and follow my doctor’s orders; I feel much better. Everyone tells me how different I am,” Rosa explains, displaying a hooked rug she made in occupational therapy—one of the many activities at the day hospital.

Though the day hospital, with its team of specialists on site every weekday, requires significant resources, it allows patients to live at home and remain active participants in their communities. Rosa emphasizes how important it is to her to be living at home and have these services nearby. She also appreciates her treatment team, which has reconciled her with relatives through family meetings convened since she was transferred to the day hospital.

Addictions and Substance Abuse

A significant portion of the work carried out at community mental health centers focuses on abuse of both legal and illegal psychoactive substances and related addictions. Cuba’s history is inextricably linked with tobacco and rum production, which has imprinted on the society a culture of acceptance towards drinking and smoking. The good news is that data from three National Surveys on Risk Factors and Chronic Disease (1995-96; 2001; 2010), show both are on a general decline. The bad news is that there are troubling trends—a slight uptick in alcohol consumption by young women, for instance, and 80% of new smokers are under 20. [2,3] Additionally, some municipalities have a much higher disease burden related to smoking and alcohol use.

“Alcohol consumption is our number one problem,” says Dr Alejandro García, director of the Community Mental Health Center in Central Havana, Cuba’s most densely populated municipality, with more than 160,000 people living in a 2.1 square-mile area. “Not alcoholics, per se, but people who consume alcohol irresponsibly, which leads to family violence, accidents and behavioral problems.” In this center, like others across the country, the response is based on a three-pronged strategy of health promotion and disease prevention, clinical care and rehabilitation—the latter associated with rigorous followup.

Specially trained in addictions, doctors and nurses here provide individualized consultations and design a treatment plan that may involve group and/or one-on-one therapy at the center. Whenever possible, families are incorporated into the treatment plan. “We regard families as ‘cotherapists’, since they can offer support and help modify behavior. Often they provide a first alert if the patient is not complying with their treatment plan; and of course, families are an important element in effective rehabilitation,” says Dr García.

The experience of Iliam bears this out: a young musician from Havana, she called the national hotline for substance abuse (Línea Confidencial Antidrogas, coordinated by MINSAP), concerned that her brother was an alcoholic. By her own admission, she was skeptical when she first called, wondering if it would really be confidential, and most importantly, helpful. “Honestly, I was incredibly impressed by the specialist who took my call. She was informed and professional and I learned a lot about alcohol abuse and the services available. That allowed me to sit down with my brother and talk about options for recognizing his problem and getting treatment.”

While the national program for mental health is standardized across all centers—including, for instance, six-week smoking cessation clinics—each municipality has the flexibility to offer services that respond directly to the health picture in their area. In the case of Central Havana, this includes treatment plans for addictions to illicit drugs. According to Dr García, “drug addiction isn’t a generalized problem in Cuba, but this municipality has the highest prevalence of drug abuse in the country—marijuana and cocaine, including crack cocaine, mostly, and often in combination.” In this case, personalized consultations are complemented by diagnostic tests, with the treatment plan coordinated by a toxicologist. Referral to a detoxification program at the hospital level may be indicated. The treatment plan always includes scheduled followup and rehabilitation, aimed at integrating the patient back into society as swiftly, effectively and sustainably as possible.

Where Cuba’s national substance abuse program most differs from other contexts facing similar health problems is in limited access to pharmaceuticals for treatment of psychoactive substance abuse, due both to resource constraints and difficulties obtaining drugs patented in the USA, whose sale to Cuba is subject to export licenses under the US embargo. This means nicotine patches and other smoking substitutes are unavailable; and some newer drugs for anxiety, depression, bipolar disease and other mental disorders, are likewise unavailable to Cuban patients.

Mental Health in Cuba, Selected Data

Sources: Anuario Estadístico de Salud, 2012. Ministry of Public Health, Cuba; *Dr Carmen Borrego, director, national mental health services and substance abuse program, MINSAP.

This scarcity provided impetus for a two-pronged approach: development of Cuban medications by the country’s biotechnology sector (including the anti-anxiety medication Centralina, which underwent clinical trials at the Community Mental Health Center in Guanabacoa, a certified clinical-trial center) and emphasis on natural and traditional medicine (NTM, the Spanish acronym). The latter includes homeopathy, floral therapy, Eastern practices like tai chi and yoga, and auricular acupressure. “The embargo limits our access to technology and medications, but we’ve seen good results using natural and traditional medicine…if there’s a specialty that has really embraced NTM in Cuba, it’s mental health,” says Dr Borrego.

Priorities and Challenges

Today, Cuba’s mental health picture is a mix of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, and more widespread, multifactoral health issues including anxiety, depression and use of psychoactive substances. This is not dissimilar from the global health picture, especially in Europe, the USA and Canada. Nevertheless, Cuba is facing challenges specific to its context requiring a coordinated national response.

One of the greatest challenges, specialists agree, is rapid population aging. Cuba has a life expectancy close to 80 years, the lowest crude birth rate in the region, and a total fertility rate below that required for generational replacement. It’s estimated that by 2030, more than one third of the population will be over 60; Cuba is on track to be one of the 11 oldest countries in the world by 2050.[7] Such longevity has implications for the mental health of older adults and their caregivers, who in Cuba are usually family members. “Aging is a difficult and complex process for the individual, the family and the community,” says Dr García. “Healthy aging—mentally and physically—is one of our highest priorities.”

Addressing the mental health of older Cubans has motivated an intersectoral, multidisciplinary approach. At community mental health centers, psychologists offer separate, specialized consultations for older adults and their caregivers, coordinated with other facilities offering services to seniors including seniors’ centers (Casas de Abuelos, in Spanish) and nursing homes (Hogares de Ancianos, in Spanish). Additionally, mental health center specialists coordinate the Caregivers’ School, where those living with and/or tending, older adults learn how to best care for seniors and improve their quality of life. Classes include proper hygiene (when and how to bathe older adults), correct nutrition (what and how to cook and optimum mealtimes) and how to provide stimulating recreational activities.

Another challenge is to encourage different sectors of society to work together. “Mental health is based on teamwork,” says Dr Borrego, “since that enables us to improve the health of all Cubans.” In practice, this starts with the individual, family and community, who work together with health professionals at the primary care level, including family doctors and nurses, and the multidisciplinary teams at polyclinics and community mental health centers. Other social actors that may be involved include caregivers of older adults, social workers, and organizations such as the Federation of Cuban Women. Schools are also important: a child’s psychologist may consult with their teacher about behavioral problems in the classroom, for instance, and beginning at junior-high level (seventh grade), teachers receive special training to give classes in prevention of drinking and smoking. Meanwhile sports and cultural institutions provide recreational activities—key to everyone’s mental health.

Guanabacoa psychiatric day hospital. / E. Añé

When asked what they considered priorities for Cuba’s mental health program today, the specialists consulted presented a variety of competing priorities. Dr Borrego from MINSAP’s mental health and substance abuse program believes “our mental health system, like the health system as a whole, needs to be more efficient and sustainable if we’re to continue improving population health.”

Dr Magalys Leyva, a psychiatrist at Guanabacoa’s Community Mental Health Center, urges “prevention, early detection, and adequate treatment and followup for suicidal tendencies.” Director of Central Havana’s Mental Health Center, Dr Alejandro García, would like to see “improved knowledge about how to manage addictions—especially recreational use of drugs, alcohol, even video games.” And Rosa Ascaño, the patient who spent over two decades hospitalized in a psychiatric institution before transferring to Guanabacoa’s day hospital, feels the highest priority is for everyone to “listen to and cooperate with their doctors. We have a responsibility for our own health, to take care of ourselves, for everyone’s sake.”

References

- Anuario Estadístico de Salud 2012. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU), National Medical Records and Health Statistics Bureau; 2013. p. 31. Spanish.

- Proyecciones de la Salud Pública en Cuba para el 2015. Havana: Ministry of Public Health (CU); 2006. p. 23, 40. Spanish.

- Reed G. New Survey Results Enhance Cuba’s NCD Surveillance: Mariano Bonet MD. MEDICC Rev. 2011 Oct;13(4):11–3.

- Health Myths and Facts [Internet]. United States: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2010 [cited 2013 Oct 20]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.mentalhealth.gov/basics/myths-facts/index.html

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2008: the MPOWER Package. [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008 [cited 2013 Oct 18]. Available from http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2008/3n/index.html

- Gorry C. Primary Care Forward; Raising the Profile of Cuba’s Nursing Profession. MEDICC Rev. 2013 Apr;15(2):5–9.

- Coyula M. Havana: Aging in an Aging City. MEDICC Rev. 2010 Oct;12(4):27–9