MEDICC Review: Many say the Cuban health system is at a crossroads today. How do you perceive its achievements, the challenges ahead?

José Luis Di Fabio: When it comes to health, Cuba is privileged in many ways. First, for five decades the country has had a universal public health system backed by political decisions that have made its development a priority. Other countries are still trying to achieve this. Cuba’s challenge is different: it’s how to maintain and sustain that system by adopting new financing mechanisms, optimizing resources, and managing technologies efficiently. This means structural redesign of some parts of the system.

Second, Cuba is also privileged with its high doctor-patient ratio and its guarantee of access to care built on a strong primary health care network, in which family doctor-and-nurse offices and polyclinics serve all residents in a local geographic area.

The challenge now is to maintain quality of care while reducing dependency on technology at some levels. To accomplish this, the Cubans are proposing more reliance on physicians’ clinical skills and more rational use of technology, especially in primary care.

For example, equipping the country’s some 450 community polyclinics with the same technology is costly, and doesn’t take into account that each facility serves a different size population with different epidemiological characteristics. So “cookie-cutter” technology distribution is inefficient and, recognizing this, health authorities are moving to optimize use of equipment, relocating it to where it makes the most sense.

Of course, the problem is that once people get used to having the technology at their community clinic, it’s difficult to convince them that their quality of care won’t suffer when it’s moved. So this becomes a concern.

Third, human resources: the fact that training of health professionals is under the aegis of the Ministry of Public Health is another advantage. This means you can better align training with the country’s needs, including locating schools in each province to ensure more equitable distribution of health professionals. This isn’t so in other countries, where such questions take up considerable negotiating time among ministries and other actors.

And finally, this health system is not about medicine as a business. Unfortunately, in many other nations, people think of medicine as a career to make money. Here, we still see the altruism of medicine as service. That isn’t to say Cuban health professionals are adequately paid—increasing salaries is recognized as one of the big challenges, even at the highest levels of government. They have to find the resources.

Looking ahead, I think Cuba faces other important challenges—including an aging population and the services it will require, and the greater capacity needed to plan for this demographic shift. This also means taking full advantage of preventive strategies at hand today.

MEDICC Review: Can you exemplify how Cuba is “plugged in” to the PAHO system regionally?

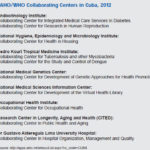

José Luis Di Fabio: One way is the designation of ten PAHO/WHO Collaboration Centers in Cuba—contributing expertise and experience to advance our regional and global agendas for health and health equity. [See box.]

The Latin American Center for Disaster Medicine (CLAMED), for example, draws from decades of Cuba’s own experience in disaster mitigation and management, as well as that of Cuban medical teams’ cooperation abroad. CLAMED trains the Henry Reeve Contingent, 10,000 specialized professionals prepared and equipped as rapid responders to epidemics, hurricanes, earthquakes, toxic spills and the like. The Contingent’s record, with its accumulated capacity and knowledge in places such as Pakistan and Haiti, is impressive; it’s also the result of having a single public health system that can quickly deploy human as well as material resources.

On another front, CLAMED has been involved from the beginning in PAHO’s Safe Hospital initiative, designed to keep hospitals and other health facilities operational during and after disaster strikes. The effort involves architects, engineers and others besides health professionals; the norms for evaluating the safety of these health facilities came originally from CLAMED. After several big hurricanes hit Cuba in 2008, we held regional workshops, and from these, a guide to mental health in disaster situations also emerged, with important Cuban participation.

One major problem remains: Cubans’ aren’t publishing enough, so their experiences are not accessible to the rest of the world. And they have a lot to offer: the article in MEDICC Review presenting results from 15 years monitoring vaccine-related adverse events in Cuban children provides information we can’t find anywhere else in Latin America or the Caribbean [see MEDICC Review, January 2012].

Yet, it took a long time coming. Part of the problem is that much of the international literature is published in English, which is an obstacle encountered by researchers in many other countries of the Americas as well.

MEDICC Review: How does PAHO work in Cuba itself?

José Luis Di Fabio: We have a country cooperation strategy through 2015, based on a set of ten priorities worked out with the Ministry of Public Health. These are consistent with the principles and priorities of the national health system, and also with the WHO’s medium-term strategic program and the Millennium Development Goals—our aim is to align all these to make more impact where we can. Much of what we do concerns efforts to strengthen the efficiency, quality and sustainability of Cuba’s health system, particularly in primary health care.

In 2010–2011, nearly US$3.4 million was assigned from the central PAHO budget to technical cooperation with Cuba, and another US$3.3 million was raised through PAHO from other sources.

One example of PAHO’s work here is our decentralized technical cooperation with local governments, related to issues ranging from maternal-child health to cancer and other chronic diseases, domestic violence, community mental health, protection of children in disasters, and healthy aging.

MEDICC Review: You mention the Millennium Development Goals, a strategy emphasizing intersectoral approaches. How do these come into play in PAHO’s cooperation with Cuba?

José Luis Di Fabio: Intersectoral approaches are vital to health, and thus to all our PAHO projects, which aim to complement other efforts at local development, including those of the rest of the UN system.

Safe drinking water, social and economic integration, education, exercise, food security, traffic safety—none of these can be addressed by the health sector alone.

We have a project just getting off the ground in Cienfuegos looking at mortality from cancer—now the number one cause of death in that province. Through the comprehensive health services network (headed by the provincial hospital, another WHO/PAHO Collaborating Center), new ways to approach this problem are being designed, relying on data from primary health care providers and other levels of the health system.

The different kinds of cancers will be mapped, and improvements devised—especially in prevention and early detection strategies—to address these where they are most prevalent. Some domestically-developed tools are also available, such as the national Immunoassay Center’s test for human fecal blood for early detection of colon cancer.

But no matter which cancer you are confronting, prevention is complicated and needs intersectoral cooperation. Just look at lung cancer in Cuba: smoking is banned in public buildings, but if this is not enforced, the health sector can’t do its job. If diet, alcohol consumption and smoking are not addressed urgently, we will see cancer rates rise; if stress is not reduced through regular exercise, more risk is added to the picture.

MEDICC Review: You mentioned the Immunoassay Center, part of Cuba’s “scientific pole,” working in biotech and other R&D. How do you view the country’s approach to biotech?

José Luis Di Fabio: The US embargo and other economic constraints have forced innovation to meet the demands and fulfill the commitment of Cuba’s universal health care system. One way is through products developed by biotech R&D. Although export revenues are derived, the main purpose is not to strike it rich, but rather to make these new vaccines and other medications available to resolve pressing health problems in Cuba and elsewhere.

The closed loop approach has worked here, in which biotech institutions cooperate from initial research, through development, trials, national use and marketing. This contribution has also benefited South-South cooperation, with Brazil and Cuba offering a case in point. Their cooperation on production of millions of doses of meningococcal vaccine A+C for Africa’s “meningitis belt” is a model of joint venture and technology transfer: Cuba manufactured the polysaccharide components and Brazil did the formulation and completed the final product, resulting in a vaccine prequalified by the WHO.

More recently, an important agreement was signed between Brazil and Cuba for technology transfer of many biotech medical products developed in Cuba. And of course, Cuba has also transferred technology to countries such as India, China and South Africa.

Photo: E. Añé

MEDICC Review: Is PAHO involved in Cuba’s global health cooperation?

José Luis Di Fabio: Some 40,000 Cuban health professionals are posted abroad in places where public health services were few or non-existent. These teams encounter realities, not just diseases, which are very different from what they see in Cuba. These include different cultures and traditions. In Bolivia, for example, women are accustomed to vertical birthing and many indigenous people don’t want to be hospitalized for fear they will be blamed for dirtying the sheets, so maligned have they been for centuries.

So, we’ve begun working with the Cuban Public Health Ministry’s Medical Collaboration Unit and others to provide more background on the history and cultures of the countries where Cuban health professionals serve, to ensure they have the best preparation possible before they go.

MEDICC Review: The Latin American Medical School (ELAM) is probably the world’s largest medical school with an explicit social mission. What is PAHO’s relationship to the school?

José Luis Di Fabio: ELAM enrolls 20,000 students from over 100 countries, and their graduates are doubtless having an impact. This program is also facing challenges in terms of inserting these new MDs into medical practice in their home countries: there is disinformation that foments ignorance. And there is resistance from some in the medical profession itself, particularly among specialists who were trained so differently. They don’t understand these ELAM doctors who were trained mainly in community settings and health facilities—something you don’t see in many countries.

So, they criticize ELAM graduates for many things, among them not receiving training relevant to local needs. In several places, Cuban medical educators have introduced an interesting innovation that addresses such concerns, in which students spend their last one or two years under the tutelage of Cuban professors serving in the students’ own countries. This is one measure that should have a positive effect and on recognition of the ELAM degree by more countries’ accreditation bodies.

Interestingly, such obstacles aren’t faced by the over 190 US ELAM students and graduates, who have to pass the same boards as those who went to school in the United States itself; or in European countries such as Spain, where the ELAM degree is recognized.

PAHO signs every graduate’s MD degree, attesting to its validity. And we would like to do more to support ELAM in its graduate outcome and impact studies through its human resources observatory program and to assist in debunking some of the myths about its curriculum. Our reasoning is clear: the world needs doctors for primary health care, doctors who come from, and are willing to practice in, distressed communities and rural areas, and who are well acquainted with their own culture and respect others.

MEDICC Review: What would you like to accomplish during your tenure here as PAHO/WHO representative?

José Luis Di Fabio: Most of all, to help share the lessons from a 50-year old universal health care system that is unique in the world.

I would also like to enhance the impact of Cuban biotech and South-South cooperation through regional vaccine and anti-retroviral production networks and through strengthening of the region’s regulatory framework. This includes involving the work done by Cuba’s National Drugs Quality Control Center and its National Clinical Trials Coordinating Center—the latter responsible for the first accredited clinical trials registry in the region.

Finally, I would like to build greater confidence in Cuba itself in PAHO’s willingness and capacity to cooperate effectively with the Cuban health system’s efforts to enhance sustainability, quality of services, and its global contribution to health equity. Such confidence must underpin everything we do: we are here to support, to help, to accompany.