INTRODUCTION

Systematic measurement of physical activity in populations constitutes an important component in public health surveillance.[1] Physical activity is defined as any body movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires more energy expenditure than resting.[2,3] There is growing scientific evidence on the protective effect of regular physical activity in relation to risk of non-communicable chronic diseases (NCD), including heart disease, cerebrovascular diseases, hypertension, non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, colon cancer, anxiety and depression, and on the benefits for cognitive capacity, mood and health-related quality of life.[2–10]

WHO rates physical inactivity as one of the 10 main causes of death and disability in the world. The Global Burden of Disease study estimated that physical inactivity is responsible for more than 2 million deaths annually and 1% of total disease burden (measured as disability-adjusted years of life lost, or DALY). Estimated global prevalence is 17% in adults (higher in women than in men).[11–12]

To produce health benefits, physical activity must meet certain requirements of intensity, duration and frequency. Current recommendations are at least 30 minutes per day of moderate physical activity 5 times or more each week, or 20 minutes per day of vigorous activity at least 3 times per week.[13–14]

Measuring physical activity is a complex process for which diverse instruments have been used, making it difficult to compare prevalence between and within countries. Development of a reliable and valid instrument and selection of an optimal method are pending challenges.[15]

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), designed by an international consensus group in 1998, has been used to measure physical activity levels in multiple populations. The short-form IPAQ has been tested in international studies. Evaluations of its reliability and validity at 14 centers in 12 countries have concluded it has acceptable metric properties, can be applied in different settings and is appropriate for population prevalence studies, given its capacity to be adapted to different cultural contexts.[15–16]

Cuba’s Public Health Projections for 2015[17] included, among other aims, an increase in the population’s systematic physical activity and decrease in numbers of sedentary adults. National prevalence estimates of these two factors have been determined by different methods in the First and Second National Surveys on Risk Factors and Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases (1995 and 2001, respectively).[16,17] There is no known previous national-level description of physical activity in Cuba using IPAQ. Thus, our objectives were to: (1) determine overall physical activity levels in the population aged 15–69 years; and (2) identify factors associated with regular physical activity. The results of this study will establish a baseline for surveillance of physical activity and help establish intervention requirements for population subgroups. The results will also facilitate comparison with past or future measurements in Cuba and other countries.[17–19]

METHODS

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted based on data from the Third National Survey on Risk Factors and Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases (2010–11), conducted to determine prevalence and distribution of the main NCD risk factors (RF). The national survey included urban and rural areas with representative estimates for each by sex and age group.[20]

The method of three-stage stratified cluster sampling in which the units of the first, second and third steps were districts (210 households on average), areas (minimum of 60 households) and sections (five households on average), respectively and the selection process are described elsewhere.[20]

Study sample size was 7915 individuals in 415 districts, incorporating 4150 households throughout Cuba. All household members aged ≥15 years were interviewed by specialized personnel trained and certified for implementing population studies. Our research included the population aged 15–69 years, the age group for which IPAQ has been validated.[14]

To determine levels of the dependent variable physical activity in the seven days prior to the survey the short-form IPAQ was used. Overall physical activity includes four basic domains: household, job-related, transportation and leisure.[14]

The variable for physical activity overall was classified as:

- active (when participants reported having walked or performed another moderately intense physical activity for an accumulated duration of at least 30 minutes per day, or in minimum efforts of 10 consecutive minutes for 5 days or more in the last 7 days, or performed vigorous activity for an accumulated duration of at least 20 consecutive minutes per session for 3 days or more in the last 7 days);

- irregularly active (having walked or performed another moderately or vigorously intense physical activity for a daily accumulated duration of at least 10 minutes, but without meeting all criteria for regular activity); and

- sedentary (not having walked or performed any other moderately or vigorously intense physical activity for at least 10 straight minutes in the last 7 days).[21]

Independent variables included in the analysis were:

- geographic area (rural, urban);

- sex;

- age group (15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54 and 55–69 years);

- education completed (none, primary, middle school, trade school, middle-level technical, high school, university);

- marital status (single, married, partnered, widowed, separated);

- employment (government; joint-venture company, i.e., a firm created in partnership between Cuba and foreign investors; self-employed; student; homemaker; retired; unemployed);

- skin color (white, mestizo, black); and

- perception of health risk associated with overweight and physical inactivity (high, moderate, low and none).

These variables were used as stratification criteria for physical activity categories and as covariants in multivariate statistical models.

Analysis Percentages and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for categories of physical activity, total and stratified by sociodemographic variables.

To identify factors associated with regularity of practice (although not for the purpose of causal inference), a multinomial logistical regression model was fitted to calculate adjusted odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals. Two sets of OR were estimated with their corresponding intervals: one for the category inactive and the other for the category irregularly active. The model included only those variables that appeared to show a clear pattern of association on visual inspection of the descriptive statistics in the bivariate analysis. The following reference categories were used for discrete independent variables:

- urban geographic area

- male sex

- government employment

- no perceived health risk associated with overweight

Except for perception of risk associated with overweight, selection of reference categories was subjective, on the basis of an assumption of least risk.

For age, ORs and confidence intervals were calculated per age increment (10 years, until reaching the oldest age group, which was 55–69 years, a 15-year increment). In the multinomial model, age was introduced as an ordinal variable with values 1 (ages 15–24 years) through 5 (ages 55–69 years).

SAS Version 9.11 was used for all calculations, taking into account the survey’s complex sampling design for adjustment and weighting of estimates and corresponding standard errors.[22]

Ethics The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Hygiene, Epidemiology and Microbiology Institute of Cuba. Study participants gave written informed consent.

RESULTS

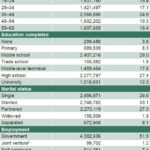

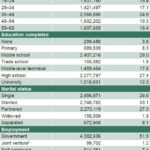

Some 76% of study participants lived in urban areas; 51% were male and 49% female. Mean participant age was 45 years (43 for men, 45 for women), with the largest group aged 35–44 years. The most populous groups for other variables were, respectively; for education, middle and high school; for marital status, married; for employment, government; and for skin color, white (Table 1).

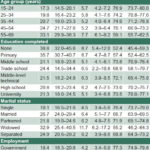

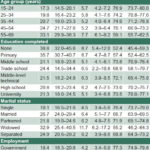

Approximately 71% of the sample reported being active, 23% as sedentary and 6% as irregularly active, with similar distributions in urban and rural areas. In both urban and rural areas, higher activity levels were reported by men. Women were more active in urban than rural areas: 63.3% (CI 60.2%–66.4%) and 48.9% (CI 43.6%–54.1%) respectively, in contrast with men: 80.8% (CI 78.2%–83.3%) and 82.7% (CI 79.3%–86.1%).

Overall, the percentage of sedentary or irregularly active people was twice as high for women as for men (Table 2).

Physical inactivity increased with age, showing modest increases for each age increment up to the group aged 45–54 years and then and a pronounced upturn in the group aged 55–69 years. It was also slightly higher among white people (Table 2). Sedentarism was substantially more frequent (more than 10 percentage points) among people with little or no schooling (primary school or less), than in the rest of the education categories, which presented similar percentages of physical inactivity (Table 2).

There was a higher percentage of inactivity among widowed men and women (32.9%). Single people presented the highest activity levels (76.4%) followed by those who reported they had a partner (71.9%) (Table 2).

Table 1: Participant sociodemographics

arounding error for some variables

bpartnership between Cuba and foreign investors

For the employment variable, homemakers and retirees presented higher percentages of physical inactivity. The most active people were found in the categories of government workers, joint venture employees, students and self-employed (Table 2).

There were no noticeable differences in physical activity patterns by skin color.

Multivariate analysis revealed associations between regular physical activity and the variables sex, age, occupation, and perception of health risk associated with overweight (Table 3). The variables marital status, education, skin color, and perception of risk associated with physical inactivity showed no discernible association with physical activity (Table 2) and therefore were not included in the regression model.

Table 2: Physical activity by sociodemographic factors, Cuba, 2010–2011

arounding error for some variables

bpartnership between Cuba and foreign investors

CI: confidence interval

Women were more likely than men to report being sedentary (OR 2.51, CI 2.12–2.98). The likelihood of physical inactivity increased (although only slightly) with age, with an OR of 1.19 (CI 1.12–1.26) for each age group increment.

The likelihood of inactivity also increased in the categories of homemaker, retired and unemployed, with respective ORs of: 1.95 (CI 1.58–2.39), 1.68 (CI 1.32–2.13) and 1.90 (CI 1.37–2.64). The odds of physical inactivity decreased, however, in the group that perceived being overweight as a high risk to health (OR 0.49, CI 0.29–0.83) (Table 3).

The pattern of association with respect to irregular physical activity was very similar to that observed in the category of physical inactivity already described above. Results are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3: Likelihood of sedentarism or irregular physical activity, regression model for selected variables, Cubans aged 15–69 years, 2010–2011

a10-year increments, except for oldest group, which is 15 years

bpartnership between Cuba and foreign investors

CI: confidence interval IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire OR: odds ratio

DISCUSSION

Introduction of a new metric is accompanied by certain reservations for comparisons with other studies in similar scenarios. But this shortcoming is compensated for by the possibilities it opens to establishing baselines, applying a validated instrument, and setting the foundation for monitoring and assessing trends.

This is the first national-level study to describe physical activity among Cubans using the short-form IPAQ questionnaire. It is difficult to make comparisons with other studies that used different methods, but the results provide a baseline for future assessments.

An estimated 70% or more of Cubans have high levels of physical activity, which means that almost one in three Cubans is in the group WHO considers at risk for cardiovascular disease and other disorders.[23]

Some studies conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean estimate that 30%–60% of the population do not meet minimum recommended activity levels. The percentage of active people reported in our study is similar to findings in Bogota, Colombia and Buenos Aires, Argentina, which reported prevalences of 36.4% and 31%, respectively, and higher than those found in Medellin, Colombia and Sao Paulo, Brazil, also using the short-form IPAQ.[24–27] It is important to note that our study is representative of an entire country, one with different economic and social conditions than those found in the cities where these studies were done.

Lower activity levels for women were observed in this study than in other studies using the IPAQ. Women tend to have less regular physical activity and perform less strenuous work than men. In addition, women typically shoulder a large part of domestic chores, manage the household and take care of the children, along with their employment, which can limit opportunities for other types of physical activity.[24–27] Similar results were reported in the USA where adequate physical activity levels were more common among men.[28]

In Chile, a 2009 national survey of physical activity and sports reported 83.7% physical inactivity for men and 88.6% for women.[29] Also in contrast to our study, Brazilian research published in 2008 found sedentarism significantly more frequent in men than in women.[30]

The inverse relation between physical activity and age we observed is consistent with other studies, in which physical activity steadily decreased with age in both sexes. It has been suggested that physical activity levels decline at a rate of 1%–2% per year.[30–32] In our study, there was a slight tendency toward increased sedentarism with age, but it was not uniform over time, with a gradual rise in early adulthood and a more dramatic upward turn in the oldest age group (coinciding with legal retirement ages in Cuba).

Our study found that a high percentage of Cuban youth self-classified as “active.” In many other countries (both developing and developed), less than one third of this group sufficiently active.[32]

Educational level has been identified as a predictor variable in multiple population studies.[7] Our results clearly show two groups with different risk profiles: people with primary school or less, and people with middle school or more. In Cuba, as part of their school day, children and adolescents receive (in the years prior to and in high school, continuing in the first years of university or vocational school) physical education classes and sports at least two or three times per week, in addition to the physical activity involved in getting to and from school and any leisure-time activity.

In Colombia, a study by Uribe[8] showed that physical inactivity in adults with only the primary or secondary education was as high as 50%, becoming less frequent as educational level rose. A Spanish study reported a change at university level, when physical activity tended to fall off.[33]

Two factors might help explain less activity in widowed Cubans. First, obviously, is their older age, which can confound the association between physical inactivity and widowhood, because likelihood of both increases with age (similarly, younger age may help explain why single people are more active than married people). Second, loss of a spouse commonly creates a certain level of anxiety or depression, which can reduce motivation to be active. We did not include anxiety and depression as variables because exploring their possible relationship with physical activity was not a study objective, but it is worth noting that lack of exercise is a risk factor for anxiety and depression, which can lead to a vicious circle of negative behaviors.[34–35]

It is not surprising that the highest percentages of physically active people are found among government and joint-venture workers, the self-employed, and students. Correspondingly, homemakers, the unemployed and retired are the least active. The first explanation is methodological and lies in the definition of IPAQ categories. IPAQ defines activity as walking and/or doing moderate physical activity, which is common for students and a good proportion of people who work, and not so characteristic of homemakers in our setting. The second explanation is the generally more advanced age of retirees and homemakers with respect to the more active groups.

CONCLUSIONS

This was the first application in Cuba of an instrument with demonstrated external validity adaptable to different cultural settings. With it, we were able to estimate that 7 of every 10 Cubans are active and to identify population groups that are most likely to be sedentary or irregularly physically active. These results lay the foundation for specialized strategies to promote systematic physical activity.

Although we found that Cubans have higher levels of physical activity than reported in many other countries in our geographic region, the fact that almost 3 of 10 respondents self-classify as sedentary shows that there is still great scope for action. The National Intersectoral Program with community participation is working to promote activities aimed at achieving greater incorporation and regularity of physical activity in the Cuban population. Such actions are an important component of any strategy to prevent and control non-communicable diseases.