INTRODUCTION

Suicide is one of the most urgent problems that health professionals face today. Worldwide, suicide attempts and deaths increase each year, and so do their negative psychological and social effects on victims, their family members and their healthcare team. It is a multifactorial issue stemming from a complex mix of biological, genetic, psychological, social and environmental factors. Its impact in terms years of life lost and pain experienced by loved ones justifies the utmost attention.[1–3]

Suicide’s impact is especially severe in adolescence, the portion of the life cycle between childhood and adulthood, and characterized by biological, psychological and sociological changes, many of which create crises, conflicts and contradictions. It includes two stages: early adolescence, 10–14 years and late adolescence, 15–19 years.[3]

Suicide in adolescents has been a growing problem for decades.[1] Suicide attempts are more frequent in adolescence than in adulthood and are more frequent than completed suicides. It is estimated that by 2020, some 15–30 million adolescents worldwide will deliberately hurt themselves. Suicide is one of the main causes of death in adolescents and, together with suicide attempts, represents 3% of adolescent burden of disease, higher than asthma, tuberculosis and AIDS, and comparable to drug abuse and violence.[2,3]

During the 2013 World Health Assembly, WHO’s first mental health action plan proposed a goal of a 10% reduction of global suicide rates by 2020.[4] PAHO declared suicide an important public health problem and resolved that its indicators should be evaluated and monitored in the Americas.[5] In many countries, suicidal behavior among adolescents is a mental health issue that must be addressed.[6–11]

In Cuba, suicide is the third leading cause of death among adolescents.[12] The National Program for Prevention of Suicidal Behavior (created in the 1980s and upgraded several times since)[13] aims to decrease suicide mortality and morbidity from suicide attempts. It focuses on searching for risk factors, patient followup and assessment by multidisciplinary teams.[14] This study’s objective was to characterize the epidemiology of suicide attempts and completed suicides in Cuban adolescents in 2011–2014.

METHODS

Study type and data sources A descriptive epidemiological study was carried out to characterize suicide attempt morbidity and suicide mortality in people aged 10–19 years in Cuba in 2011–2014. Data sources included morbidity records for suicide attempts from notifiable disease cards and suicide death certificates in the mortality database of the Cuban Ministry of Public Health’s (MINSAP) National Medical Records and Health Statistics Division from January 1, 2011 through December 31, 2014.[12]

Variables For suicide attempts variables were sex (male, female) and age group (10–14 and 15–19 years). Variables for suicide were the same as for suicide attempts, plus occupation or employment status: student, unemployed, homemaker, with an incapacitating disability, and other (includes armed forces, skilled and unskilled workers, middle-level professional or technician, office workers and unknown) and methods used for suicide (hanging, poisoning, firearms, self-immolation, jumping from high places and intentional motor vehicle collision).

Data collection, processing and analysis Authorization was requested from MINSAP’s Medical Records and Health Statistics Division to collect information. Notifiable disease cards and death certificates were the primary sources. To classify cause of death (intentionally self-inflicted injury), we used ICD 10 codes X60–X84.[15]

The following were calculated: suicide attempt and suicide mortality rates per 100,000 population by age group (crude, age adjusted and sex specific); sex ratio (male:female); and attempt:suicide ratio. Rates were directly standardized by age group and sex to Cuba’s 2012 population. Relative change in rates was calculated and percentages were used to show distribution of variables (sex, age, occupation or employment status, and suicide methods) to indicate respective burden.

Medical Records and Health Statistics Division code books were used for the abovementioned variables. An Excel database was created to store and manage data and to generate tables and graphs.

Ethics Only morbidity and mortality records were used. Anonymity of patients and the deceased was preserved, and data were used exclusively for this research, which was approved by the National Hygiene, Epidemiology and Microbiology Institute Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

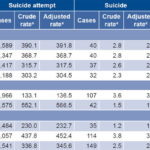

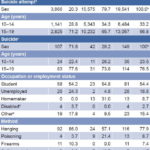

Suicide attempts There were 19,541 suicide attempts reported (4885.2 per year on average), a crude rate of 336.8 per 100,000 population for the period. The age-adjusted rate in 2011 was 391.8 per 100,000 population (hereinafter, rates reported are age adjusted, unless otherwise specified). In 2014, the rate dropped to 304.5 (Table 1), a 22.3% reduction.

At the beginning of the period, the rate for suicide attempts in boys was 139.2 per 100,000, and decreased to 127.5 in 2014 (relative decrease of 8.4%). In girls, the rate was 658.7 per 100,000 population in 2011 and decreased to 491.6 in 2014 (relative decrease of 25.4%).

Table 1: Suicide attempts and suicides in Cuban adolescents, 2011–2014

a rates per 100,000 population / b cumulative rates per 100,000 population

There were 6484 suicide attempts reported in the group aged 10–14 years, a rate of 232.7 per 100,000 population. The 2011 rate of 253.4 per 100,000 fell to 209.1 per 100,000 population in 2014, a 17.5% reduction. In the group aged 15–19 years, there were 13,057 attempts, for a rate of 452.4 per 100,000 population. In 2011, the rate was 522.5, decreasing to 394.8 per 100,000 population in 2014, a 24.4% reduction. Sex ratio for attempted suicide was 0.25:1. The attempt:suicide ratio for the period was 131:1. Girls made 371 attempts per successful suicide and boys made 37 (Table 1).

Suicides Between 2011 and 2014, 149 suicides were reported (37.2 per year on average), for a rate of 2.6 per 100,000 population (Table 1). The rate was 2.8 per 100,000 population in 2011 and 2.3 in 2014, a 17.9% reduction.

There were 107 suicide deaths among boys, for a rate of 3.7 per 100,000 population (Table 1). The rate in 2011 was 3.9 per 100,000 population, decreasing to 3.5 in 2014, a 10.3% reduction.

Girls accounted for 42 suicides, for a rate of 1.5 per 100,000 population (Table 1). The 2011 rate was 1.6 per 100,000 population, dropping to 1 per 100,000 population in 2014, a 37.5% reduction. The overall sex ratio for 2011–2014 was 2.5:1 (107/42).

There were 35 suicides in the group aged 10–14 years, for a rate of 1.2 per 100,000 population (Table 1). In 2011, the rate in this group was 1 per 100,000 population, increasing to 1.6 in 2014, an increase of 60%.

The group aged 15–19 years had the highest mortality, with 114 deaths and a rate of 3.9 per 100,000 (Table 1). The 2011 rate of 4.4 per 100,000 decreased to 3 per 100,000 population in 2014, a 31.8% reduction. This group comprised 66.8% of the population but 76.5% of suicide deaths during the period (Table 2).

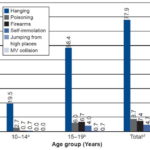

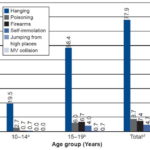

Students accounted for 54.4% of all suicide deaths (Table 2). Hanging was the most commonly used suicide method (77.9%), in all age groups (Figure 1) and in both sexes (Table 2).

Table 2: Suicide attempts and suicides in Cuban adolescents, by selected variables, 2011–2014

a n = 19,541 b summed horizontally (all other series sum vertically) c n = 149 d incapacitating e includes armed forces, skilled and unskilled workers, middle-level professionals or technicians, office workers and cases with unknown occupation

Figure 1: Suicide method by age group in Cuban adolescents, 2011–2014

a n = 35 b n = 114 c n = 149 MV: motor vehicle

DISCUSSION

There is considerable recent literature on risk factors for suicide. Depression, desperation, impulsiveness, violence, alcohol and drug use, school failure, low cultural and economic levels, chronic diseases, immigration, bullying (psychological, moral and/or physical harassment at school, where one student exerts power over another systematically with intent to cause harm) are the most commonly invoked factors. [16–21]

Poor family communication, frequent quarrels, lack of affection and cohesion among family members and overall lack of support, are main factors that contribute to suicidal behavior in children and adolescents.[22] Home and school are the contexts in which most risk factors for suicidal behavior can develop, but at the same time can offer many opportunities to detect factors and stigmas that can lead to suicidal ideation.

Some researchers argue that the global economic crisis, globalization and advanced technologies contribute to increased suicidal behavior during adolescence, arguing that stress associated with a faster pace of life, conflicts and competition leads to desperation and tension during a critical period in life in which psychological, sociological and biological changes make adolescents especially vulnerable.[23] Despite its socially inclusive system and the special protection afforded vulnerable groups, these problems also affect Cuban adolescents.

In Cuba, young people are increasingly exposed to modern technologies and audiovisual products. A study of Cuban adolescents reported notable increases in video gaming and Internet addiction.[16] Such addictions are known to accentuate loneliness, reduce psychological wellbeing and affect socialization and psychomotor development in adolescents.[16] In addition, young people’s increasing access to the Internet exposes them to images and other visual information about self-destructive behavior, or other apocalyptic content, all of which can have quite harmful effects.[17,18]

The 60% increase over the study period in suicide rates in the group aged 10–14 years is consistent with international studies reporting that suicide is increasingly frequent in early adolescence. This may be due not only to traditional risk factors, but also to technological development in recent years. Modern technologies have changed our relationships. We no longer rely on face-to-face interactions. A child alone in their bedroom can be in touch with dozens of people, but this tends to foster weak connections, superficiality, short-term relationships and ultimately, social isolation.[24] Overreliance on technology, if combined with lack of parental supervision or a dysfunctional family environment, can have negative effects on adolescent behavior and might help explain why suicidal behavior and thoughts historically attributable to adults, are occurring among youth in our societies.[24]

Attempted suicide is considered a psychiatric emergency.[13,14] Cuba’s National Program for Prevention of Suicidal Behavior has established a protocol for all such attempts. A mandatory note is entered on the notifiable disease card of those who attempt suicide, for followup by the patient’s basic primary care team (family doctor, nurse, pediatrician, clinician, OB/GYN, psychologist) and mental health team (psychiatrist, psychologist, nurse, social worker) in their municipality. This aimed at timely treatment and monitoring by psychiatric specialists after initial assessment. Reports on assessment and evaluation of the Program in selected municipalities have revealed both strengths and weaknesses. One Program evaluation study reported that 72.9% of cases had been monitored satisfactorily in clinics and on-site visits, as stipulated, and that in the remainder of cases, monitoring was not possible due to incorrect addresses or family refusal.[25] Another report detected lack of compliance with the Program.[26] However, these results are not representative of Cuba as a whole. When the Program functions properly, it is a valuable resource for suicidal behavior prevention.

Previous studies in Cuba have reported increases in suicide attempts in Cuban adolescents in 2011 and 2012, but none of them had national coverage.[27–29] No such increase was apparent in our national study. On the contrary, there was some decline in suicide and suicide attempts in Cuba over the study period, less in boys than in girls, although boys had lower initial rates. Attempts declined more than completed suicides.

The suicide rate in Cuban adolescents (2.6 per 100,000 population) is less than that reported by the Region of the Americas between 2005 and 2009, 3.7 per 100,000 population (5 in boys and 2.3 in girls). Rates of 4.4 and 3.5 per 100,000 population were reported in North America, and Central America and the Spanish Caribbean, respectively.[30] In contrast, suicide rates in Spain are lower than those we found: in 2010, 0.1 per 100,000 population for the group aged 10–14 years, and 1.2 per 100,000 population for the group aged 15–19 years.[24]

In Colombia, suicide attempts have been reported as early as age seven years, although with rates gradually increasing with age, and more frequent in girls.[31,32] The higher frequency of suicide attempts among girls is consistent with our findings.

Although children aged less than 10 years are not included in our study and will be the subject of another paper, there is considerable literature sounding an alert about suicidal behavior in children.[33–36]

As seen elsewhere, the number of suicide attempts far exceeded completed suicides; the attempt:suicide ratio was within the range of a Spanish study that found ratios of 100–200 attempts per suicide.[37]

The relation between suicide attempts and suicide is clearly sex-related, with girls more likely to attempt and boys more likely to complete. Our finding that boys were more affected by suicide coincides with PAHO’s technical report, which states that in the Americas Region, boys have higher suicide rates across all age groups.[38] In other regions, it has been reported that completed suicide is two to five times more frequent in boys, consistent with our findings.[39] In Cuba, the suicide sex ratio has been increasing among adolescents.[40] A study carried out in Mexico reported that 68.4% of suicides occurred in boys,[41] which is lower than in our study. A 2.2 sex ratio in this age group was reported for the Americas, while for Central America, Spanish Caribbean and Mexico, it was 1.7,[38] lower than ours. China and India are the only countries in which suicide rates in women are higher than in men.[42]

The highest number of attempted and completed suicides occurred in the group aged 15–19 years, consistent with other studies reflecting that risk is higher in late than in early adolescence.[24] In Mexico, this age group also presented the highest percentage of suicide cases (78.2%), even higher than in our study.[41]

Most suicides occurred among students. This might simply reflect the fact that the vast majority of youngsters in Cuba are students.[43] Cuba offers free education for all, and school attendance is compulsory up to age 14 years; in 2015, 91% of secondary-school-aged youth were enrolled.[44] A Spanish study found that suicide risk was five-fold higher among youngsters who abandon school and eight-fold higher in those without postsecondary education.[45]

Suicide methods depend on availability and access. Our finding that the most commonly used suicide method in this study was hanging is in accord with other research reporting that hanging is most common in ages 10–19 years, as it is inexpensive, easy and does not require laborious planning.[32,41] Hanging is also the most frequent suicide method in Central America, the Spanish Caribbean and Mexico (65.2%), as well as South America (59%), although by smaller margins than in Cuba.[38]

Poisoning ranked second in our study, as it did in PAHO’s Report on Suicide Mortality in the Americas, which placed poisoning at 23.5%, more than double the percentage in Cuba. Poisoning is the most common method in the non-Spanish Caribbean, at 47.4%.[38] In some high-income countries, different methods are more frequently used. In North America, predominantly in the United States, firearms were the number one suicide method among boys and young men.[38]

The study’s main limitation was its inability to obtain reliable information from secondary sources on other geodemographic stratification criteria that could have helped create broader, more complete epidemiological insights into socially related causes of suicide or suicide attempts.

Despite this limitation, the study provides important baseline information on the characteristics of attempted and completed suicide among young people. It gives visibility to attempted suicide, a problem for which Cuba is one of the few countries reporting data to PAHO/WHO, although it is not included in MINSAP’s annual statistical yearbook.[12] While current trends do not point to a marked decline in completed suicides, there have been substantial decreases in attempted suicide.

There are very few Cuban publications on suicide, especially among adolescents. The information obtained here provides an essential basis for other, more specific family or individual studies regarding causes of suicide and suicide attempts. Such studies will help Cuba design and implement more effective prevention strategies to address identified causes of preventable morbidity and death. As a collateral benefit for future research and surveillance, a complete database is now available for researchers to contact families and monitor adolescents at risk. Although our study does not and cannot purport to establish causal associations, it provides the epidemiological basis for further studies seeking causal factors.

CONCLUSIONS

Suicide rates in Cuba are lower than those reported elsewhere in the Americas and overall suicide attempt and suicide rates decreased somewhat between 2011 and 2014. However, there is no room for complacency. The highest suicide rates occur in the group aged 15–19 years, but rates in those aged 10–14 years are increasing. Hanging is the most commonly used method. Boys are more likely to commit suicide, but girls more likely to attempt it. These results update the epidemiology of suicide in Cuba in the group aged 10–19 years and demonstrate the extent of the problem for one of the main preventable causes of death in Cuban adolescents. Thus, these findings alert us to the need to take action to further reduce rates of suicide and suicide attempts in Cuban young people.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our thanks to Silvia Serrá Larín and María del Carmen Hinojosa Álvarez for assistance with the literature review.